Chapter 11: Technology Integration in the Practice of Family Professionals

11.1 Technology Integration in the Practice of Family Professionals

Even if you’re on the right track, you’ll get run over if you just sit there.

― Will Rogers

Chapter Insights

- For family professionals, technology skills and knowledge are critical competencies in the 21st-century workforce.

- Digital citizenship straddles is both a content area for family professionals, and something that must be integrated into practice for ethical and effective delivery of care and services.

- Family professionals’ integration of technology is dependent on attitudes toward technology use, attitudes that are based on models such as Davis’ (1989) that frame use as related to intention, acceptance and attitude, and perceived ease of use and usefulness. Research with family educators validates this framework and identifies workplace conditions as directly and indirectly related to attitudes.

- Individuals’ technological comfort and competence benefit from training that occurs in professional preparation programs and in continuing education. Preparation is often shaped by professional standards of practice inclusive of technology use. Professional standards are present in licenses (e.g., teachers, therapists) and certifications or credentials (e.g., Certified Family Life Educator).

- Family therapists can be guided by organizations such as

- the American Counseling Association and

- the American Association of Marriage and Family Therapists, which have standards for ethics, client safety, and confidentiality.

- Family educators can be guided by standards of technology integration

- for educators in formal settings (such as the International Society for Technology in Education, iste.org) or licensing standards set for teachers at the state level.

- standards collaboratively constructed by professional associations, including the National Council on Family Relations, the National Parenting Educators Network, and the American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences

- The COVID-19 pandemic greatly impacted family professionals’ comfort, use, and innovation in using technology to deliver programming to families. Research with family educators, for example, indicates that tremendous accommodations and innovations were embraced to address the far-ranging needs and preferences of families and children. Supportive resources for professionals greatly facilitate comfort and skill, and address educators’ own feelings of isolation and being overwhelmed.

- After reading this chapter, identify what you feel inspired by, the questions that remain for you, and the steps you can take for your own technology use to be more intentional.

Family Professionals

So far, this book has primarily focused on the ways in which families use technology in their lives; the impacts of technology on relationships, human development, and family life; and the research and policy that guides our understanding. But what of the professionals who work with families? In many ways, they are the ones who translate what we know about technology to family members so that the information is useful and meaningful.

Family professionals work full-time in a wide array of fields — as couple/marriage and family therapists; family financial counselors and educators; family and consumer science teachers; Extension educators specializing in home economics, nutrition and foods, financial management, parenting, family life, and more; parenting and/or family life educators, and in family social service administration and coordination. The focus on family-focused professional service is not limited to those whose work is full-time and/or with a title that specifically indicates work with families. In 2017, the author surveyed family educators from several national membership organizations that employ family practitioners (Walker, 2019). Approximately one-fourth of respondents represented fields that would not be traditionally considered “family-first,” including clergy, psychologists, teachers, academics, researchers, and business leaders. Key to our focus in this chapter is that practitioners deliver service to families, parents, and children directly in some way, service that may include integrating technology in ways that help enhance individual and family life.

Given family members’ use of technology for acquiring information, sharing content, and supporting individual and shared goals, ICT offers an obvious avenue for professionals to reach wider audiences and new methods for effective delivery. The intersection of family practice and technology is twofold: 1) as a vehicle through which to assist parents and families with learning how to effectively use and choose technology for their children (e.g., technology as a content area for parenting education), and 2) tools and a virtual environment for the delivery of family services, including family therapy, services for families, and parent and family education. Family professionals integrate knowledge about technology as a reality for family life into their practice, and deploy that knowledge when assisting families across myriad issues and interests.

A couples and family therapist, for example, may aid a young couple experiencing conflict over social media sharing or mobile banking, or may facilitate decision-making with families when children are ready to use a smartphone. And they use technology in their practice. The COVID pandemic pushed many family professionals to find creative ways to continue outreach, communication, and service delivery (LeBouw, 2020). This meant adopting social media, videoconferencing, preparing full classes and courses for online environments, and trying out innovations amidst fears around privacy and comfort. The pandemic pushed family professionals further into a phenomenon now present in their practice.

In short, technology use is not a “one-off” topic for family professionals. It is a new reality of family life and for family professionals that requires considerable understanding and critical perspective for professionals’ effectiveness with families and their comfort, skill, and competence in engaging effectively and ethically in practice.

This chapter focuses on how family professionals use technology in their work, and on avenues to professional development regarding technology. To that end, it also addresses the forces that promote quality in technology use as an area of family professionals’ work, and avenues that provide guidance and support. We begin with a quick look at the intersections of types of family work, then look at the value of using technology in family practice to see how technology can be applied in practice. Then we consider the skills and competencies needed for family professionals in the 21st century, particularly as they relate to integrating technology into practice. This means possessing digital citizenship skills, and the acquisition of these skills. There are three primary avenues to professional development that promote and reinforce (or can act as barriers) to development: pre-service preparation, continuing or professional development, and ongoing workplace conditions. Each of these will be explored, with attention to professional standards and current research. The chapter ends with recommendations on technology integration in family practice.

The Intersections of Family Practice

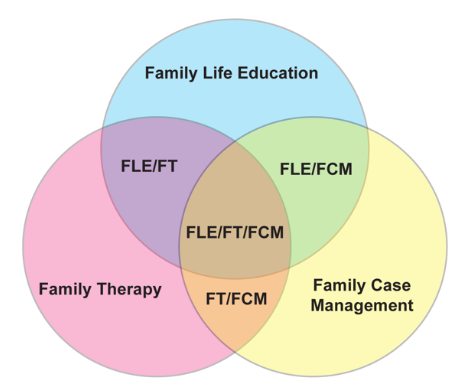

To best situate technology as both content and delivery in family practice, we begin with a scope of competencies and areas of specialization. Myers-Walls et al. (2011) delineate the boundaries and intersections of family practice across education, therapy, and service fields (see figure below). All dimensions embrace family systems theory, include an ecological context, are sensitive to diversity, follow research-based practice, and hold to professional values. Differences occur in practice specificity — for example, in family education the focus is education and prevention, with an emphasis on normal, healthy functioning. Family therapy features therapeutic intervention, assessment and diagnosis, and psychotherapy. Family Case Management involves family advocacy, meeting family needs and coordinating services. As demonstrated in the figure, each element has overlap with the others. For example, family life education and family therapy intersect through the life course perspective, and encouraging interpersonal relationship skills. Family life education and family case management intersect through family policy (and a solution focus) and in family resource management. All domains intersect through an adherence to family systems theory, and the ecological context, a sensitivity to diversity and marginalized populations, reliance on research-based practice, and values and ethics (if this feels familiar these too are the foundations to this book).

Family Education

Family educators may work in a specific area, such as parenting education or family financial management, or may be generalists (known decades ago as “home economists”). They may be employed in any range of settings — corporations, nonprofits, religious organizations, hospitals, schools, and local, state, and federal governments. In Minnesota, where the author lives, the Early Childhood Family Education program (ECFE) is offered through all school districts to provide parenting education and early childhood enrichment for all families. The program employs licensed teachers, including those holding state teaching licenses in parenting (Minnesota is the only state that offers a license in this content area). Parenting educators in ECFE work full- or part-time as school district employees, and have bachelor’s or master’s degrees. More information about parenting educators can be found through the National Parenting Education Network (npen.org). The National Council on Family Relations offers certification in Family Life Education. More about the CLFE can be found at https://www.ncfr.org/cfle-certification .

Family Therapy

In family therapy, intervention is therapeutic and may include psychotherapy. The focus of the therapist’s work is short-term and solution-focused. According to the AAMFT website, Marriage or Couple and Family Therapists (MFTs)

are mental health professionals trained in psychotherapy and family systems, and licensed to diagnose and treat mental and emotional disorders within the context of marriage, couples, and family systems…. They evaluate and treat mental and emotional disorders, and other health and behavioral problems, and address a wide array of relationship issues within the context of the family system. Marriage and family therapists broaden the traditional emphasis on the individual to attend to the nature and role of individuals in primary relationship networks such as marriage and the family. MFTs take a holistic perspective to health care; they are concerned with the overall, long-term well-being of individuals and their families.

These therapists graduate from accredited post-graduate preparation programs, and are licensed by the states in which they work. The American Association of Marriage and Family Therapy (AAMFT.org) provides credentialing standards for programs of higher education that ensure quality and ethics in supervision and training. MFTs may work in a wide range of settings as well, including private practice, government agencies, and nonprofit mental/health organizations, and in research and teaching,

Family Case Management/Family Service

In family case management, the focus is on meeting family needs, family advocacy, and coordination of services. Case management is a component of most licensed social workers’ practice (according to the NASW), and is a specific role adopted by those in the field. According to the NASW:

With its strengths-based, person-in-environment perspective, the social work profession is well trained to develop and improve support systems (including service delivery systems, resources, opportunities, and naturally occurring social supports) that advance the well-being of individuals, families, and communities. Furthermore, social workers have long recognized that the therapeutic relationship between the practitioner and the client plays an integral role in case management. (p. 8)

The Use and Value of Technology in the Delivery of Family Practice

New technologies and digital media can be integrated in family practice for outreach, evaluation, and assessment of learning; to foster discussion for sharing information and perspectives; in the delivery of content; and to facilitate social connections beyond face-to-face meetings (e.g, Blum, 2021; Breitenstein et al., 2014; Darling et al., 2020; Taylor & Robila, 2018; Walker, 2020). This can reduce the cost of program delivery and reach larger numbers of people without sacrificing effectiveness or participant satisfaction (Jones et al., 2014; Kumpfer et al., 2015). And it can mean tailoring to specific audience needs. Technology design addresses the wide-ranging and complex needs of contemporary families (e.g., Alford et al., 2019, addressing smartphone use in foster care). In formal education, technology has long been promoted to help instruction and learning inside the classroom and out (Haythornthwaite & Andrews, 2011; UNICEF, 2017). Technology integration in family practice also reflects growing interest and use by family members. Podcasts, websites, blogs, apps, social media, videos, and mobile applications have been utilized worldwide in the last 20 years (Hall & Bierman, 2015; Myers-Walls & Dworkin, 2015; Suárez-Perdomo et al., 2018).

Family technology researchers observe several areas for growth: program implementation evaluation to include more socioeconomically and culturally diverse populations; attention to device innovation (e.g., the move from desktop to mobile); identifying mechanisms to accommodate wider audience needs and address access inequities; building program delivery on learning theory; and comparisons of online-only, and hybrid (face-to-face plus online) applications.

Bullock and Colvin (2015) observe the history of technology use in social work practice and examine contemporary challenges to integration. In the 1980s, clinical practice involved one-way mirrors with clients to allow for interdisciplinary and team participation in assessment and training. Later in that decade, social work services on the internet emerged as online self-help support groups. By the 1990s, groups of clinicians offered online counseling services to the public using secure websites. Today, social work services include a much wider range of digital and electronic options. These allow social workers to engage clients through email, texting, or video teleconferencing using web cameras. Social workers who refuse to acknowledge technology as a practice trend risk falling out of step.

Piercy et al. (2015) identified a variety of ways in which marriage and family therapists used technology in practice. Interview research with 63 practicing therapists (18 male and 45 female) showed that technology related to business management (e.g., outreach, marketing, administrative services), assessment of clients, psychoeducation, direct treatment, the offering of self-help resources, and accountability. Face-to-face therapy was enhanced through the use of media, instructional videos, and psychoeducation materials. Therapists indicated that some clients were better able to communicate with technology, given their experiences of social anxiety.

Online educational and intervention programs

Evidence-based parenting programs and other face-to-face, short-term programs have been adapted to electronic delivery, including electronic text, audio, video, and interactive components delivered via the internet, DVD, or CD-ROM. Early evidence indicated promise for time efficiency (cutting down on travel cost, implementation), participant completion, maximizing intervention fidelity, and sustainability (Breitenstein et al., 2014).

Nieuwbower et al.’s (2013) meta-analysis of 12 studies of internet-based parenting education applications found short-term benefits to knowledge and attitudes. Their study included programs of 2–15 sessions, with professional and in some cases peer support, deploying novel applications, including instruction by animated characters, remote coaching, progress monitoring, and video vignettes. Spencer et al.’s (2020) meta-analysis of 28 published studies, and Corralejo and Rodriguez’s (2018) and Hall and Bierman’s (2015) analysis of technology-adapted parenting education programs, observed the inconsistency in results and scope of the evaluations, from those indicating feasibility and a high degree of satisfaction with parents and/or staff, to those with more rigorous evaluations that demonstrated impacts on short-term outcomes in parenting, parent confidence, or child behavior. The majority of the studies focused on interventions for parents of young children. Spencer et al.’s analysis, for example, identified only 3 of 28 programs for parents of children 12 or older. And Corralegjo and Rodriguez (2018) observed the need for more research and applications offered in non-English languages. Researchers also observe the need to attend to participation, as rates of attrition seem high with online-only applications.

The availability of online delivery of parenting education programs is so prolific that clearinghouses identify programs that align with populations, topics and outcomes. In some states and countries, parenting education is mandated for divorcing parents or as a first-level response for parents who have been reported to have abused or neglected their children. Online delivery makes completing these requirements convenient. Research on adaptations to existing face-to-face programs has demonstrated positive, albeit short-term, results. Variations of this research include examining wholesale adaptations of evidence-based parenting education program to online delivery (Hall & Beirman, 2015; Long, 2016; Neiuwbower et al, 2013; Spencer et al, 2020), hybridizing online delivery with person-to-person contact (Day & Sanders, 2018), and an online component to complement face-to-face delivery (Love et al., 2016; Walker, 2017). Some of this research is discussed below.

Triple P parenting has adopted its EBP intervention program to technological interfaces with a television series, an online version (Turner & Sanders, 2011), and recorded podcasts (Morawska et al., 2014), all demonstrating short-term effects greater than those in control samples. Day and Sanders (2018) examined clinical outcomes, program engagement, and satisfaction in a random control trial of the online Triple P parenting program, the online program with telephone consultation by a trained practitioner, and no treatment. The supplemented online component revealed greater benefits in reducing overall negative parenting and frequency of child behavior problems. Participants reported greater satisfaction with the program and showed higher rates of module completion than did either the online-only group or the no-treatment group.

while self-directed online programs have value to knowledge acquisition, influencing parenting attitudes and translation to practice are best accomplished with a social, guided component. Similar evidence was found when the self-administered and technology-adapted Incredible Years program incorporated professional coaching and access to an interactive forum (Taylor et al., 2008). Nieuwbower et al. (2013) also asserted that while self-directed online programs have value to knowledge acquisition, influencing parenting attitudes and translation to practice are best accomplished with a social, guided component. This suggests that, while online parenting education can be designed to be user-friendly and to integrate learning design principles (Hughes et al., 2012), including social interaction and direct connection to the practitioner may provide social capital and learning benefits that exceed the value of self-directed learning alone. Deploying mixed methodologies that include a social component may be key to reaching diverse audiences.

Social components can be added to online applications that complement face-to-face parenting education. When the Triple P Parenting program incorporated social media and gaming features (e.g., badges as incentives to participation) in outreach with a highly vulnerable population, outcomes for reducing child behavioral problems, permissive or over-reactive parenting, and parental stress were improved (Love et al., 2016). Respondents appreciated the flexibility, anonymity, and shared aspect of the online community. And a web platform for ECFE parents (Parentopia, introduced in the About the Author page) and staff to connect between classes (or to act as a supplement when parents couldn’t attend face-to-face) proved effective at strengthening social connections and a sense of identity in program affiliation (Walker, 2020). A key was in participatory design of the technology to align with program community orientations, values for parent inclusivity in language and access, and repeated usability testing to make the platform user-friendly (Walker, 2017).

Family education technology researchers observe the need for improvement in the study of online programs: inclusion of more socioeconomically and culturally diverse populations, attention to modern devices (e.g., mobile), building program delivery on learning theory (reviewed programs were absent in theory), and comparisons of tech-only and technology-plus applications. Four of the evaluations in Breitenstein et al.’s (2014) review were of evidence-based programs delivered exclusively online (including the Incredible Years and Triple P parenting). The authors suggested a controlled comparison of online and in-person applications with the same intended program outcomes (parenting skills, parent-child interactions, and children’s outcomes), and suggested that a cost-benefit comparison was warranted for full assessment. After research of in-person programs with investigations of their online adapted counterparts, Nieuwbower et al. (2013) observed that the results of online adaptations cannot be assumed from in-person outcomes. Online delivery is different, and includes many variables to consider in effective deployment.

While research on the design of technology-enriched or online delivery of parenting education is still in its infancy, lying in wait is research on the implementation of these systems for effective and sustained delivery. Forgatch et al. (2013) observed the implementation process of the Parent Management Training Oregon model (PMTO) with community service systems and the search for fidelity in program implementation. They identified a two-system (adopting community and program developer) and four-stage (preparation, early adoption, implementation, sustainability) model that characterizes the many considerations. The PMTO scholars also note the benefits of using technology in program implementation and fidelity. A centralized database incorporating video intervention sessions permitted reliability checks of raters, and a centralized website enabled program leaders to fine-tune implementation and oversight of facilitators’ competence. As the PMTO model has been replicated in multiple states and countries (including Iceland, Norway, and Mexico), online data management enables efficient implementation on a global scale. Even so, the authors raise a number of questions about policy and practice that reveal the added complexity of using ICT in program implementation.

Digital Skills Required for a 21st-century Family Professional Workforce

In 2017, The National Academies of Science (NAS) offered predictions of workforce needs in the 21st century relative to information technologies. They …observe that the ultimate impacts of technology will be determined by technical capabilities, how technology is used, and how individuals, organizations and policy makers prepare for and respond to shifts in the economic and social landscape.the National Academies of Science (NAS) offered predictions of workforce needs in the 21st century relative to information technologies (IT and the U.S. Workforce: Where do we go from here?). They highlight the growth of artificial intelligence and “smart” devices, and observe that the ultimate impacts of technology will be determined by technical capabilities, how technology is used, and how individuals, organizations and policy makers prepare for and respond to shifts in the economic and social landscape. Sadly, without adaptation, professionals could face real consequences.

The NAS calls on the educational system to adapt. Worker skills will require creativity, adaptability, and interpersonal skills over routine and manual tasks, and as noted in Chapter 9, there will be growth in on-demand employment. The NAS also called for multidisciplinary research and improved tracking of the workforce and of technology development.

More recently, the Pew Internet and American Life project interviewed 90+ leaders about the future and about employment skills relative to technology. There was agreement that work would be more flexible and less bounded by time or place, and would require workers to have adaptable skills.

Related to family professionals, in 2016 Nicholas Long offered these predictions for practitioners of parenting education:

- There will be an increase in studies that examine how provider knowledge, training, and skills impact the effectiveness of different parenting education services.

- There will be an increased focus on identifying core competencies as well as ethical guidelines for parenting educators.

- There will be a growing interest in certifying those who provide parenting education services (beyond program-specific certification).

- There will be a greater focus on how to most effectively train and supervise providers of parenting education services.

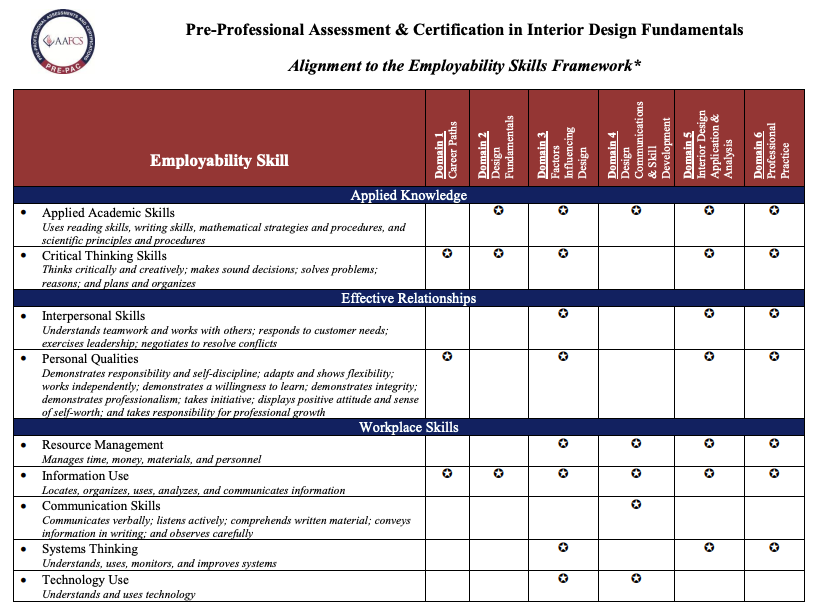

And the American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences (AAFCS) highlighted technological skills as a necessary component of workplace skills in the “employability skills framework” for the 21st century, as complementary to applied knowledge and effective relationship skills.

As indicated above, media and technology skills are also recognized by the AAFCS as key competencies, along with learning and innovation skills and life and career skills.

In writing about the application of technology to family therapy, Piercy et al. (2015) observe shifts in human behavior and the perception of meaning through both symbolic interaction and social constructivist lenses. Social constructionism believes meanings are transitory and developed through interaction and social agreement. When couples use digital technology, they are creating relationship through online interaction and, even more, are constructing couple identities, expressing themselves as couples, and negotiating the meaning that technology offers to their relationships. The authors also note that, while cyberspace can enhance perceptions of and opportunities for intimacy, it can also reflect deception and fraud. Examples abound of being “ghosted” or “cyberstalked,” and of personal information being used without permission. From such interactions, individuals interpret and make meaning, creating symbolic worlds that can shape behavior. Couples come into therapy having constructed a narrative of themselves through these online interactions — narratives and self-identities which therapists must accommodate. Piercy et al. (2015) hold that it is essential that therapists are aware of the force online interactions can hold for relationships and intimacy. And Blum (2021), who has used TikTok as a medium for relationship and therapy education, warns that users may disregard boundaries and perceive that a therapist’s presence online is an invitation to begin 1:1 therapy.

As educators such as Mike Ribble observe, being a good digital citizen is a requirement for us all, as information technologies are now a part of our daily life. This means having the knowledge to use technology intentionally, and in ways that ensure safety along with effective use. To that end, we require not just digital skills, but a full understanding of information technology as it can impact human life. We need to possess the qualities and knowledge of a good digital citizen. Family professionals assist couples, parents, and families in using media in healthy ways, and understand areas of potential conflict that family members can resolve together.

Digital citizenship

To begin a discussion of technology skills, knowledge, and comfort for family professionals (Godfrey, 2016) is to center on the Elements of Digital Citizenship (Ribble, 2015). These provide broad categories of consideration for safe and effective use of the internet and of information and communications technologies:

- Digital access: full electronic participation in society

- Digital commerce: electronic buying and selling of goods

- Digital communication: electronic exchange of information

- Digital literacy: basics of technology and its use

- Digital etiquette: electronic standards of conduct

- Digital law: electronic responsibility for actions and deeds

- Digital rights and responsibilities: freedoms extended to all in a digital world

- Digital health and wellness: physical and psychological well-being

- Digital security: electronic precautions to guarantee safety

Further clarification of these elements can be found in Godfrey’s article (p.19), and in these scenarios created for teachers.

Digital citizenship strands have been simplified into four dimensions, along with what the Dig Cit Doctors call “enduring understandings:”

Digital Citizens keep themselves and each other safe.

Enduring Understandings:

- Laws, rules, and social norms govern digital spaces.

- Digital identities, data, and online activities are commodities.

- Individuals and organizations may misrepresent themselves online.

Media Information and Literacy

Digital Citizens responsibly consume, create, and share digital content.

Enduring Understandings:

- Effective search strategies help individuals locate information online.

- Digital information varies in value, quality, and reliability.

- Media influences individual perceptions and societal actions.

- Technology can be used to express and amplify ideas.

Digital well-being

Digital Citizens prioritize their digital well-being and the well-being of others.

Enduring Understandings:

- Self-awareness and the use of intentional strategies can support a healthy digital diet.

- Online personas are constructed reflections of an individual’s identity.

- Technology may play a role in both advancing and impeding human connection.

Social Responsibility

Digital Citizens are socially conscious and empowered to influence change.

Enduring Understandings:

- Digital citizens have a collective responsibility for the ethical design, use, and regulation of new technologies.

- Technology is a powerful vehicle for civic engagement.

- Technology both highlights and perpetuates social inequities.

Framework for teaching digital citizenship

Family educators — whether teaching in formal settings, such as higher education or secondary schools, or in non-formal settings in work with parents — can teach elements of digital citizenship. Ongoing shifts in technology device availability and in applications used in formal education, informal learning, and social worlds (e.g., TikTok, Schoology) mean that parents need to stay current for active engagement, anticipate challenges, identify probable hacks, and provide guidance. Parenting education can acquaint caregivers with relevant information on children’s developmental domains and age stages to help parents understand what children are capable of and responsible for as they navigate their presence online, face potential threats, and reap creative and collaborative rewards.

Educators can assist parents and families with vetting the quality of material when choosing what to read. Parents are curious about how to know when children are ready for smartphones, how much screen time is healthy, preventing threats to privacy and safety, and preventing cyberbullying. And parents vary in their ability to discern differences in online information and in skills that relate to education and literacy. As parents use technology in their roles as parents — texting and video calls to communicate with children and to reassure and coach their children through challenges, learning alongside children with education technologies, and sharing the joy of gaming — parenting education can help promote the value and use of these new media and possibly create new rules for parent-child communication. Finally, parents may need help navigating these spaces, as they too can be subject to social comparison, bullying, and overuse.

When new technologies and workplace policies mean the navigation of flexible work, home, and space boundaries, family professionals can help working parents acquire “digital cultural capital.” This isn’t an exhaustive list of topics that can be covered by family educators, but indicates some of the many elements of parenting and family life that naturally integrate technology.

Ribble (2015) offered a four-stage reflection framework for teaching digital citizenship that can be applied to traditional, formal classroom instruction and non-formal learning opportunities for parents and families:

- Being aware of technology use and its appropriate use. Students are asked to reflect on their technology use at home and at school.

- Guided practice.

- Modeling and demonstrating. Teachers as well as adults need to practice good digital citizenship habits in their own lives.

- Feedback and analysis. It is important to have a classroom environment where students feel comfortable in discussing how they use technology at home and at school.

Family Professionals and Competency Standards Indicative of Technology Skills and Knowledge

Each of the family professional speciality areas have competency standards that guide preparation and practice; within these lie opportunities to integrate technology as both a knowledge and skill area for professionals. Competency standards are used to inform state and national licensing, as well as credential and accreditation requirements, in turn informing the creation and selection of curricula offered in higher education programs of professional preparation. They are also used to inform professional development opportunities, conference themes, and training. And professional standards inform job descriptions and requirements used by employers of family professionals. In short, these standards hold tremendous importance in shaping practice direction and innovation.

Family Education

The National Parenting Education Network (NPEN) framework on the competencies of parenting educators finds content knowledge bridging both parenting and human development, along with knowledge of the practice of parenting education (figure below). Competencies also include requisite skills to practice and deliver parenting education. These include:

- Foundations of parenting education

- Adult learning and education

- Educational methodology/instructional design

- Working with parents in groups

- Working individually with parents and family (home visits, one-on-one instruction, consultation, coaching)

- Assessment and evaluation

- Relationships and communication with parents and families

- Professional behavior and development

At the center of the competencies are the educator’s attitudes and dispositions (Wadlington & Wadlington, 2011). These include professional conduct (e.g., accepts responsibilities), professional qualities (e.g., demonstrates a commitment to the individual student), and communication and collaboration (e.g., displays sensitivity in interacting with others, UMN, 2017). And all dimensions are informed by ongoing developments in research and theory. For those who practice family life education, working as family and consumer sciences teachers, financial or nutrition educators, or in other family-related specialities, guidelines for practice with technology can be found by professional bodies that promote quality teaching and support teachers.

Technology standards in formal teacher preparation

State teacher licensing includes standards for teaching with technology. In Minnesota, where all teachers must demonstrate competency in teaching standards and in content related to their content area license (e.g., science education, preK-grade 3, parenting and family education), teaching standards include a specific section related to technology competence, with the following elements:

- Technology-enriched learning environments

- Diverse learning

- Assessment

- Discrimination

- Technological knowledge

- Digital citizenship

- Contribution to the teaching profession

- Broadening student knowledge about technology

- Variety of technologies

Competency 2H, for example, reads “demonstrate knowledge and understanding of concepts related to technology and student learning;” Competency 3R reads “identify and apply technology resources to enable and empower learners with diverse backgrounds, characteristics, and abilities.” And 9M reads “understand the role of continuous development in technology knowledge and skills representative of technology applications for education.” These standards are created with guidance from professional bodies for teacher development, some of which specialize in technology. The Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP) covers the following technology themes within their seven standards areas:

- Student learning

- Clinical practice

- Technology integration

PK-12 instructor standards groups, including the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) (https://www.iste.org/standards) and the Interstate Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium (InTASC), identify more specific technological themes:

- Modeling (ISTE)

- Real-world issues (ISTE, InTASC)

- Reflective learning (ISTE)

- Communication (ISTE, InTASC)

- Global awareness (ISTE)

- Leadership (ISTE)

- Research / Professional practice (ISTE, InTASC)

- Technology integration (InTASC)

- Professional engagement (InTASC).

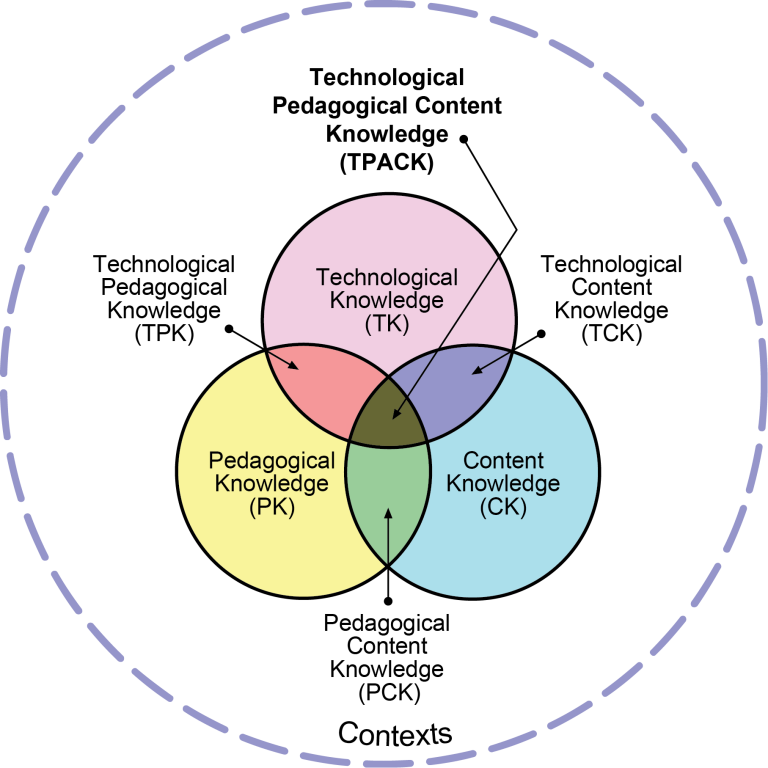

Formal education technology theory, research, and practice, inclusive of teacher preparation, has much to offer family education as a basis for how to understand, integrate, and study technology integration and educator support. The TPaCK framework, for example, identifies the intersection of using specific technologies (T) to enhance pedagogical practice (P) and enrich content knowledge (CK) delivery (Mishra and Kohler, 2006; figure below). Other models promote technology selection to align with learner activity levels (passive to active) and desired instructional outcomes of Replace, Augment, Transform (e.g., PICRAT, Kimmons, 2012), or translate particular technology use aligned with traditional learning theories or frameworks, such as Bloom’s taxonomy (Churches, 2010).

Because many who practice family education are not working in formal settings or do not hold teaching licenses, there are likely to be differences in practitioner preparation and oversight. Most definitely there are differences in practice. Those who work in non-formal education often have adults (21–60+ years) as an audience. The participants’ attendance is for enrichment and is often voluntary, not for degree acquisition. Therefore, learner motivations for attending are different. Learning needs are more experiential and problem-focused. These adult learners find value in support and a feeling of community, as much as in knowledge and skill acquisition.

Family education technology integration standards

Standards specific to family education technology integration that match the specificity and breadth of formal classroom (e.g., K-12) teacher preparation do not exist. The American Association of Family and Consumer Science (AAFCS) offers guidance that informs family and consumer science teachers and Extension Educators focused on family and consumer science. Specific to family education, groups like the National Council on Family Relations have standards for Certified Family Life Educators (CFLE). Certification requires demonstration of competence in knowledge across nine content areas and in education methodology. Although technology knowledge and skill is represented in these standards, it is more generally addressed: https://www.ncfr.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/FLE-Content-and-Practice-Guidelines-2014-objectives.pdf.

There are sub-specialties in parenting education informed by the National Parenting Education Network (NPEN), in nutrition or health education informed by certification with the National Commission on Health Education Credentialing, and in finance education informed by the Financial Educators Council. Readers are encouraged to explore the specific standards set out by each body for specificity and inclusion of technology knowledge and skill.The National Parent Educators Network (NPEN) has standards for professional and paraprofessionals in parenting education. Within these standards, specifics related to technology as content expertise or in teaching are both implied and explicit. Even so, adherence to national standards related to technology integration in family education and in its specific content areas, like parenting education, varies greatly.

Unlike the discipline of formal education, with its infrastructure of federal and state government involvement, licensing requirements that align with state policies and mandates, and a century of research and professional organization through groups like the American Education Research Association and the National Education Association (nea.org), family education does not have a strong, centralized national presence that directs practice or the preparation to practice. Efforts toward competencies are thus decentralized and inconsistent, and the inclusion of technology is even more fragmented and precarious.

In the U.S., for instance, NPEN (npen.org) lists practice by state, revealing requirements for paraprofessional, professional, degreed, and licensed (MN) educators. While as a network they can offer standards of practice that are inclusive of technology skill for delivery, and these may inform practice, they don’t dictate training or certification in ways that bodies such as those for social work and family therapy do, as discussed below. Until there are more unified efforts toward both family educator standards of practice and preparation, guidance and training on technology will continue to be fragmented and, sadly, dependent on the individual or workplace. In a U.S. study of 722 parent and family educators, the majority (74%) indicated “learning on my own” to a moderate or major extent as the training that prepared them to use technology (Walker, 2019). Reports of training by professional development (50.6%) or in college (42.6%) were lower. Only one-third reported needing technology training to maintain a professional credential, and nearly all of these were licensed teachers.

Family Therapy

Couple and family therapists are guided in practice by competencies set by associations such as the American Counseling Association (ACA), the American Association of Marriage and Family Therapists (AAMFT), or the National Association of Social Workers (NASW). The ACA’s 2014 edition of ethical standards was the first to include a discussion of social media in practice in the section on Distance Counseling, Teletherapy and Social Media (section H, pp 17–18). The section speaks to informed consent and security, knowledge and legal considerations, distance counseling relationships, client verification, records management and web maintenance, and the use of social media. The AAMFT includes a section on technology-assisted services (section VI) in its ethical standards. As in the ACA guidelines, this section covers delivering services through telehealth, informed consent, confidentiality, documentation and the privacy of records, and professional responsibilities. In part, these guidelines concern the delivery of services beyond traditional place-based therapy — in other words, jurisdiction considerations that cross state or country lines. They also identify the boundaries of professional identities — when, for instance, maintaining separate accounts as a professional and as a private citizen (e.g., virtual professional presence).

Given research by Piercy et al. (2015) that indicates the range of ways in which technology is used by family therapists, while it is very appropriate that professional associations address ethical concerns when using the internet to delivery therapy, there are numerous skill sets needed to effectively deploy technology in practice.

Family Service and Social Work

In 2017, a collective of professional associations for social work — the National Association of Social Work (NASW), the Association for Social Work Boards (ASWB), the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE), and the Clinical Social Work Association (CSWA) — created Standards for Technology in Social Work Practice. The work’s table of contents, below, indicates the breadth and depth of interest in the topic as implemented in the field and in preparation of professionals:

Table of Contents for Standards for Technology in Social Work Practice

Section 1: Provision of Information to the Public

- Standard 1.01: Ethics and Values

- Standard 1.02: Representation of Self and Accuracy of Information

Section 2: Designing and Delivering Services

- Standard 2.01: Ethical Use of Technology to Deliver Social Work Services

- Standard 2.02: Services Requiring Licensure or Other Forms of Accreditation

- Standard 2.03: Laws That Govern Provision of Social Work Services

- Standard 2.04: Informed Consent: Discussing the Benefits and Risks of Providing Electronic Social Work Services

- Standard 2.05: Assessing Clients’ Relationships with Technology

- Standard 2.06: Competence: Knowledge and Skills Required When Using Technology to Provide Services

- Standard 2.07: Confidentiality and the Use of Technology

- Standard 2.08: Electronic Payments and Claims

- Standard 2.09: Maintaining Professional Boundaries

- Standard 2.10: Social Media Policy

- Standard 2.11: Use of Personal Technology for Work Purposes

- Standard 2.12: Unplanned Interruptions of Electronic Social Work Services

- Standard 2.13: Responsibility in Emergency Circumstances

- Standard 2.14: Electronic and Online Testimonials

- Standard 2.15: Organizing and Advocacy

- Standard 2.16: Fundraising

- Standard 2.17: Primary Commitment to Clients

- Standard 2.18: Confidentiality

- Standard 2.19: Appropriate Boundaries

- Standard 2.20: Addressing Unique Needs

- Standard 2.21: Access to Technology

- Standard 2.22: Programmatic Needs Assessments and Evaluations

- Standard 2.23: Current Knowledge and Competence

- Standard 2.24: Control of Messages

- Standard 2.25: Administration

- Standard 2.26: Conducting Online Research

- Standard 2.27: Social Media Policies

Section 3: Gathering, Managing, and Storing Information

- Standard 3.01: Informed Consent

- Standard 3.02: Separation of Personal and Professional Communications

- Standard 3.03: Handling Confidential Information

- Standard 3.04: Access to Records within an Organization

- Standard 3.05: Breach of Confidentiality

- Standard 3.06: Credibility of Information Gathered Electronically

- Standard 3.07: Sharing Information with Other Parties

- Standard 3.08: Client Access to Own Records

- Standard 3.09: Using Search Engines to Locate Information about Clients

- Standard 3.10: Using Search Engines to Locate Information about Professional Colleagues

- Standard 3.11: Treating Colleagues with Respect

- Standard 3.12: Open Access Information

- Standard 3.13: Accessing Client Records Remotely

- Standard 3.14: Managing Phased Out and Outdated Electronic Devices

Section 4: Social Work Education and Supervision

- Standard 4.01: Use of Technology in Social Work Education

- Standard 4.02: Training Social Workers about the Use of Technology in Practice

- Standard 4.03: Continuing Education

- Standard 4.04: Social Media Policies

- Standard 4.05: Evaluation

- Standard 4.06: Technological Disruptions

- Standard 4.07: Distance Education

- Standard 4.08: Support

- Standard 4.09: Maintenance of Academic Standards

- Standard 4.10: Educator–Student Boundaries

- Standard 4.11: Field Instruction

- Standard 4.12: Social Work Supervision

Standards such as these are a response to the work of social work practice observers such as Bullock and Colvin et al. (2015), whose research indicates the tensions in the field among practitioners more or less comfortable with using technology in practice.

Workplace Support and Professional Development

As noted, standards for practice in family professions serve many purposes in guiding practitioner training and development, informing curricula in higher education majors and career development programs, and guiding credentialing and licensing of professionals before practice begins. Technology has become a popular topic in professional development, with content foci on technology use by children, privacy and ethics, effective applications, and, in particular COVID-19 and the near complete transfer of delivery from in-person to online. In family therapy, for example, the American Counseling Association offers professional development workshops and materials on cyberbullying, and the American Association of Marriage and Family Therapy offers a network to assist with telehealth questions.

Yet a middle ground for professional support on technology use lies in the everyday practice and context of practitioners. Since 2010, the author has conducted research on technology use by parent and family educators and on workplace conditions that influence technology acceptance. Repeatedly, whether sampling educators in a single state and practice emphasis (e.g., parenting education in Minnesota, Walker & Hong, 2017) or nationwide with a diverse sample of 700+ educators representing multiple dimensions of family education (Walker, 2019; Walker, et al., 2021), the findings validate workplace conditions as a significant influence. Those perceiving higher workplace supports in infrastructure (e.g., encouragement) and resources (e.g., access to devices, training) report more accepting attitudes toward technology and are more likely to use a range of technologies.

The research model adopts Davis’ (1989) Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), which stems from concepts of behavioral intention (e.g., Ajzen, 1989). Technology attitudes accepting of innovation and information and communications technologies drive the intention towards use, and the use of technology itself. Two factors related to acceptance are PE — perceived ease of use, and PU — perceived usefulness. PU is influenced by PE (this makes sense, since if we believe something is easy to use we are more likely to find it useful to our purposes). Modifications of Davis’ original model include consideration of external conditions, such as in research of preservice teachers in Singapore by Teo et al. (2008).

From our national sample of 722 family education professionals, the perception that technology was easy to use, and the perception that technology had value to their work were directly related to technology acceptance attitudes. Workplace supports were indirectly related to attitudes and had a direct influence on perceptions of technology use and value. Validating this model to align with the conditions and practice of family educators (Walker & Kim, 2015), the author later investigated the role of workplace conditions (Walker, Lee, & Hong, 2021). Although “use” was measured in the studies, it was not used as the dependent variable, since an objective measure of use cannot be determined for a field as wide-ranging as family education. Rather, the models predicted acceptance attitudes, a more flexible indicator of use as conditions, learner needs, and types of applications change. Technology attitudes and the attitude precursors of PE and PU were adapted from measures by Teo et al. (2009). These are 5–7 item constructs, with responses measured by a 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree). Examples included usefulness (e.g., “Using technology will improve my work”), and ease of use (e.g., “I find it easy to get technology to do what I want it to do”). Workplace conditions were measured by a 12-item index from Papanastasiou and Angeli (2008), also measured by a 5-point Likert scale. Workplace attitude constructs of workplace infrastructure (e.g., technology support, devices, including “A variety of hardware and software is easily available for me to use in my program) and workplace encouragement (e.g., discussions about technology, including “I often exchange ideas about technology use with other Parent Educators”). Our analysis method used Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Path Modeling. As previously noted, from our sample of 722 national family educators, technology attitudes were related directly to PE and PU. Workplace encouragement and workplace infrastructure indirectly influenced acceptance attitudes as mediated by PU and PE, respectively. Workplace encouragement also showed a small but direct influence on technology acceptance.

Research like this provides support for examining the primary and often enduring context that shapes family educators’ practice and technology use, and for advocating for conditions conducive to innovation and accommodation with new media. Yet the reality is that family educators are irregularly held to technology standards in the workplace. While some mention the receipt of devices or training by their employers (also highly variable, and far less likely for those who are self-employed or working with non-profits), few note that use of technology is a performance standard for review or for hiring (Walker, 2019). Moreover, workplace conditions of family and parenting educators vary even more greatly, with some workplaces offering tangible encouragement (e.g., performance assessments) and support (e.g., training and technical support) specific to technology use, while most others do not. Parenting educators, occasional family educators (e.g., teachers, counselors), and family life educators vary from those in higher education/administration, who have more technology resources, report more positive attitudes, are more confident about their skills, and view formal technology training as useful. These disparities indicate that those preparing family educators may not have realistic ideas about workplace conditions, and are therefore not adequately preparing or filling the gaps needed by practitioners. They also validate the sense that those working on the front lines with parents and families face less supportive conditions, which weakens their ability in practice.

COVID-19 Impact on the Delivery of Family Practice and Education; The Use of the Internet and Information and Communications Technology

The COVID-19 pandemic provides us with the best evidence for advocating for family professionals’ knowledge and comfort with technology. The pandemic started while we were working to resolve tensions around the use of technology in practice, the value of teaching online or delivering therapy at a distance compared with face-to-face encounters, and the degree to which practitioners deploy new media in their work. Schools, organizations, and businesses were shuttered, and the delivery of service relied on the internet and on the ability of professionals to adapt.

Using her association with Early Childhood Family Education in Minnesota, the author conducted research with educatorswhen COVID hit programming in the spring of 2020, and again one year later. As COVID began, educators were fearful, yet optimistic. They felt that they could adapt their programming, yet knew that they needed strong administrative support, including technology resources. Primarily, they worried for families — that families would not be able to access programming and that those marginalized would be especially vulnerable. They hoped that whatever initiatives were implemented would be sensitive to these needs. When there is stress on existing systems for program delivery, like that brought by the pandemic, the weaknesses in providing for technological training and support are evident. These are quotes from educators faced with adapting their programs for COVID:

With so little planning time, and support for the technology available through the district, It really felt like the train left the station without [me].

At one moment, I would feel ineffective, as though I was working in a vacuum, putting material for families out into a void where it wasn’t doing anyone any good. And I felt selfish for wishing I would hear from families, knowing that they were likely stressed and overwhelmed. I struggled to know that there was anything that I was doing — to meet any real needs.

One year later, and with a sample representative of the whole state and distributed by parenting, early childhood educators, and program coordinators (with some holding two or more roles), educators reported on an amazing array of accommodations used to reach families at home during the pandemic. Smaller, more rural programs could continue with reduced classes, face-to-face. All programs needed to deploy the internet and technology applications for outreach, teaching, and assessment. More than 90% reported using email and videoconferencing (e.g., Zoom); approximately half reported using technologies like social media, a school website, a learning management system, texting programs like Remind, and YouTube.

Sensitivity to differences in parents’ technology skill can mean knowing how to adapt instruction for the greatest attention and engagement. During COVID-19, for example, parenting educators in Minnesota moved group-based discussion and the early childhood learning component to video conferencing (Walker et al., 2020). Within weeks, however, they learned that families were overwhelmed with screens by the end of the day. The educators lowered expectations for attendance, and found other creative ways to engage online (e.g., asynchronous video posts, collaborative tools) and safe face-to-face methods for families to engage in smaller numbers. They also addressed equity through the use of take-home learning packets provided by the district (at no cost to parents), loaned tablets and wifi hotspots, and worked with districts to redistribute budgets to accommodate parents with limited technology access.

Educators expressed pride at pulling together to offer flexible opportunities for learning for parents and children and ways for family relationships to stay strong, along with sadness that more resources weren’t offered to help reach more families and that technology assistance was fair at best (Walker et al., in press). Nearly one-fifth reported receiving no resources, and the majority indicated that their own experiences and support from their peers were the best methods for learning how to use technology. Being “thrown into the fire” of having to use technology did prove to be a good teacher and confidence booster. When asked to compare their proficiency with technology at the beginning and end of the school year, educator ratings (out of 10) changed from a mean of 4.98 to 7.84, a statistical difference significant at p < .001. For many, the experience was mixed, with triumph in maintaining programs to meet families’ needs, and the reality of the challenges faced in making that happen. As one educator said:

So many things! It was an honor to work with families. It was exciting, draining, and everything in between to be able to design, develop, and implement online ECFE classes. I was discouraged often, feeling like I was missing the mark, and then I’d rebound and realize that the work we were doing was potentially the most important of my career to date. At times I was lonely. And I feel intense gratitude for my EC colleague who hung in there and worked so hard for families.

Recommendations for the Future

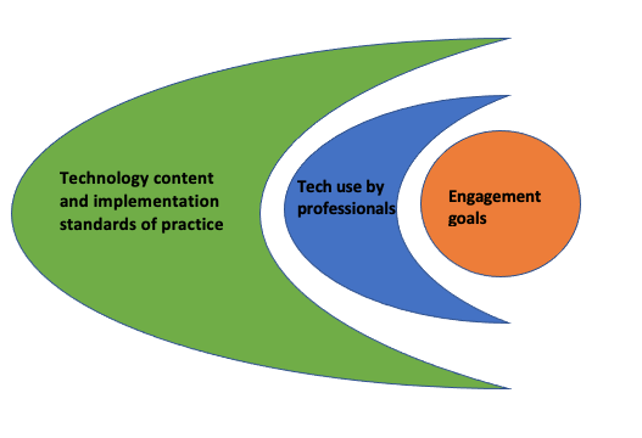

To address the ICT needs of families means continuing research that translates to practice that fully assists families with managing new digital realities. It also means that we do not assume that family professionals are supported or prepared to integrate technology in their practice. We must identify necessary competencies and standards that will drive preparation, professional development, and workplace conditions (Walker, 2016). The figure below show practitioners who work with families on the issue of technology use as the center of service delivery and as supported in their digital citizenship knowledge and skills by wider bodies of professional development and oversight:

There are additional ways to lend support to professionals. Ttechnology integration, for example, can be included in the higher education curriculum of family science, social science, education, and other applied fields. The University of Minnesota course accompanying this book — FSOS 3015 Families and Technology — is a way to stimulate critical perspectives on the many ways in which technology impacts children and family life. Association professional development efforts can include technology integration as a topic area, conference theme, podcast, or blog series. Online Community of Practices/Professional Learning Communities can focus on technology integration to offer peer ideas and assistance. And agencies can work individually or, as the NASW did, collaboratively to create standards for practice and advocate for their inclusion in licensing or performance. Additional recommendations include the following:

- Family professionals are naturally situated to aid children and families with the growing responsibilities and challenges for decision-making and wise use of new media and interactions in a virtual world. This means seeing technology as both a content area in practice as well as a means for service and education delivery.

- Family professionals must feel comfortable and competent as digital educators and integrators. Therefore, they need professional standards that guide preparation and practice. Standards developed for classroom teachers and/or the helping professions (e.g., social work, NASW, 2017) may inform recommendations for the range of those who work with families.

- Research on technology integration in family practice is still in its early stages. Adapting and testing new ways to communicate, convey information to, assess, and encourage community with parents has yielded valuable information about the costs and benefits from instructor and learner perspectives.

- Industry can build on the expertise of family professionals in the design of apps and online platforms. This includes parenting apps, for example, that may build on algorithms to tailor advice to parents and also include the rich context of childrearing decisions and influences. Those creating financial education apps, or interactive platforms to teach children money management, can work with family professionals with expertise in this area.

We now move to our final chapter: integrating policy with family practice and research on technology use and impacts.