Chapter 1: Ten Truths about Technology

1.1 Ten Truths about Technology

Change is inevitable; growth is intentional.

― Colin Wilson

Chapter Insights

- Although our use of the internet is just 30 years old, and seemingly ubiquitous devices like smartphones have been around for less than 20 years, observations about digital media and “technology” offer us a foundation of basic “truths” with which to dig deeper.

- Although we may use the shorthand term “technology” to refer to information and communications technology (ICT), we must be cautious. “Technology” is a general term, and we have various, more specific ways to talk about ICT.

- The ICT devices and applications we use help fulfill a range of functions for us as individuals and as families.

- Because research on technology is relatively new, and technology innovations continue to develop, using research findings to craft clear guidelines on use is a challenge. Current research has significant limitations in scope, sampling, methodologies, and more. Technology innovations do, however, mean new ways to gather and analyze data.

- An ecological perspective enables us to see our ICT use not just in terms of individuals, but as having an impact on and being impacted by our contexts and social connections, and by wider forces such as institutional policies, research, and industry.

- To date, we can identify a great number of benefits to individuals, families, and societies in the US and internationally from ICT use. At the same time, we have learned that ICT presents significant challenges to our relationships, communication, development, learning, and work.

- Equitable access to the internet, to devices and to the development of skills for using ICT, is a significant factor influencing differences in how technology is used.

- After reading this chapter, identify what you feel inspired by, the questions that remain for you, and the steps you can take for your own technology use to be more intentional.

Introduction

When I went to college in the mid-1970s, the weekly call to my parents meant waiting in line to use the pay phone in the dormitory hallway. It was a collect call, meaning I’d go through an operator who would ask the person who picked up if they’d accept the charges. Or I could write a letter. Registering for courses meant long lines and a half day in the gymnasium, going from table to table to get a form signed by the department (IF there was room in the course; if not the search continued in another line). For classes, we sat in lecture halls taking notes with pen and paper. Professors lectured at a podium, using a chalkboard and the occasional overhead projector.

Tests were ONLY taken in the classroom. Books were hard copies, purchased at the bookstore. Term papers were written by hand or on a manual typewriter. And doing research for those papers meant finding books using a card catalog, and articles in large, published volumes of the journals, hidden away in the “stacks.”. The only way to communicate with professors was to wait outside their offices during weekly “office hours.” Pizza was ordered over the phone (though delivery was possible), and when Saturday Night Live (SNL) was on, we’d jockey for floor space to view the TV in the dormitory common room.

Consider your college experience today. Everything just described can feasibly be done on your smartphone and you’d never need to leave your bedroom. Remember Covid-19 [1]? (Of course you do). The internet [2]and ICT enabled us to continue participating in life, even under quarantine. Today you can call, text, videoconference, or email your parents anytime (and they you). Textbooks (while often still available in hard copy) may be offered as e-versions, purchasing can be done online, and many can be rented. Class registration and course planning, ordering pizza, finding journals, and taking notes for the term paper? Online. Platforms like Google Docs make collaborative note taking or group work efficient (this book was written on Google Docs so I could share it with the folks helping me publish it). Missed SNL? You can stream it on demand.

As you compare what it was like in the 1970s (and, let’s face it, the 1980s and the first half of the 1990s) with your ICT-accessible life today, is there anything you might even envy about a world without the internet, where our idea of personal technology was a corded landline telephone? Or does the idea seem simply unfathomable (or, go ahead and say it, revolting)?

My intention is not to sing the praises of the “good old days.” Indeed, the efficiency of ICT in our lives offers us unparalleled (for now) opportunities for social interaction, information, and news gathering, and for creativity and productivity. The United Nations, Division of Economic and Social Affairs identified technological change as one of four megatrends affecting families (along with urbanization, migration and climate change). As we will explore throughout this book, while we have gained much, there is so much more we need to know. We are still in the infancy of understanding ICT’s capabilities — and its dangers. The rapid rise in technology development makes it difficult to turn around usable research results. By the time all the necessary protocols are followed, data collected and analyzed, and reports prepared for public, professional and policy consideration, the device or application studied may be outmoded. Research has revealed a great deal about who uses which types of technologies for which purposes under which conditions, we have an initial sense of impact (as you’ll read in this book), and scholars are learning both new questions and new methodologies. The Screenome Project, for example, enables researchers to analyze the realities of smartphone use through thousands of screen captures (Brinberg, et al., 2021). But while new technologies for information and communication are being developed, and our consumption and use alone and together offer fodder for research, the many unanswered questions put us in pioneer territory.

And undeniably, our use of devices like smartphones can raise a few eyebrows:

A friend posted this picture on Facebook, taken while people were waiting for a cruise. Our own use makes technology seem personal, yet when observed in large groups like this we begin to see how technology has shifted the ways in which we relate as a society.

And questions of culpability arise when behaviors once contained by place move to virtual spaces. In the early 2000s, before university policies had evolved to address virtual learning, I encountered an issue while teaching online before . For weeks, a student posted erratically in discussion forums, creating havoc in student discourse and learning, with behavior that stole focus from the content of the course. In a traditional classroom, I could talk to the student privately, even barring them from returning to the classroom while they were being disruptive. Yet back then, barring a student from the learning management system (LMS) used to deliver all components of the course prohibited access to all course materials. After many hours of discussions with university policy makers unfamiliar with how online learning operated, a timely yet equitable workaround was reached. By then, the offending student understood their disruptions and class continued in peace. The upside is that the event triggered the need to develop new policies for a new environment and new mechanisms for student learning and instruction.

Similarly, in response to issues with e-commerce, security breaches, identity thefts, and children’s exposure to the internet, new policies and laws have been created. This book was written for the spaces of our use between innovation, eager consumption, earnest research, and policy action and sound practice, spaces that call on us to be both educated and intentional about our use of technology. Particularly for families who bear the significant responsibility of caring for their members — in many cases raising children to adulthood — and thriving as a unit, ICT offers tremendous value yet at a significant level of understanding.

To set the stage for our close examination of technology use and the family, we begin with a set of “truths” about information and communications technology.

Technology Truths

#1. Technology can be interpreted to mean many things.

In our daily language (and in this book) we refer to our use of “technology.” Although we may use this shorthand term to indicate our use of smartphones and the internet, in its strictest sense “technology” refers to “the use of science in industry, engineering, etc., to invent useful things or to solve problems.” (Merriam-Webster). In fact, any novel device developed for problem-solving, such as pencils or maps, can be considered technology. More specifically to our interests here, Wikipedia defines “information and communications technology (ICT)” as that which “stresses the role of unified communications and the integration of telecommunications (telephone lines and wireless signals) and computers, as well as necessary enterprise software, middleware, storage and audiovisual, that enable users to access, store, transmit, understand and manipulate information.” This brings us closer to what we’re really discussing in this book.

Throughout this book although we will shorthand with the word, ‘technology,’ we primarily will be referring to information and communications technology. ICT spans a range of devices, software to run applications, and the applications themselves. Yet it’s important that our thinking isn’t limited to the devices we currently use, like computers, gaming devices, smartphones, and tablets. Futurists see us using glasses that read books and enable us to feel like we’re in the setting, or headgear that allows us, for instance, to enjoy a virtual landscape in South America.

The internet

Within our broad sense of ICT is the “internet,” Per wikipedia, “the global system of interconnected computer networks that uses the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) to communicate between networks and devices. [3] The internet carries many applications and services, most prominently the World Wide Web, including social media, electronic mail, mobile applications, multiplayer online games, internet telephony, file sharing, and streaming media services. Most servers that provide these services are today hosted in data centers, and content is often accessed through high-performance content delivery networks.” The internet is the virtual environment in which information (as data) is gathered, shared, and engaged with. Two common aspects of the internet are the World Wide Web and, within that, social media.

The World Wide Web (WWW)

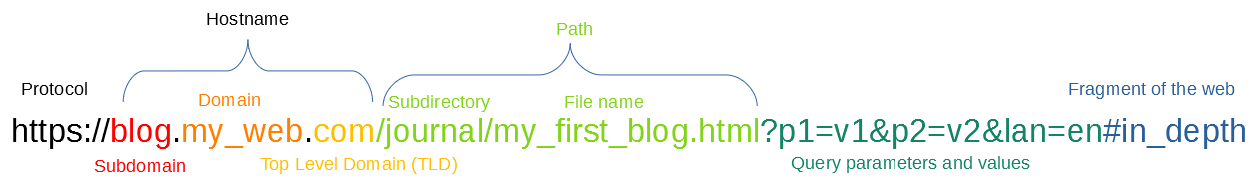

When we “go online” we generally mean that we’re connecting to the World Wide Web[4], or to a website which is a compilation of web pages. The web is “is an information system enabling documents and other web resources to be accessed over the Internet…. Documents and downloadable media are made available to the network through web servers and can be accessed by programs such as web browsers. Servers and resources on the World Wide Web are identified and located through character strings called uniform resource locators (URLs), as shown above. The character string https://www.wikipedia.org is an example of a URL.

Breaking down the web address, http:// or https:// refers to the communication protocol used for the information’s transmission. The “s” indicates when secure information, such as passwords or identifiers, is being shared. The domain is the hostname (which includes the www, though it often isn’t shown). Host server domain names are controlled by ICANN (the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers). *.com, *.net, *.edu, and country-level identifiers (e.g., *.en, *.us, *ie) refer to top-level domain names.

Social media

Social media, or social networking services (SNS), “is an online platform which people use to build social networks or social relationships with other people who share similar personal or career content, interests, activities, backgrounds, or real-life connections…. Social networking sites allow users to share ideas, digital photos, videos, and posts, and inform others about online or real-world activities and events with people within their social network. While in-person social networking — such as gathering in a village market to talk about events — has existed since the earliest development of towns, the web enables people to connect with others who live in different locations across the globe (dependent on access to an internet connection to do so).”

Social media scholars have leaned on the functionality of the internet application, such as for self-presentation to broad or narrow audiences (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2020, Fig, 2, below). By Carr and Hayes’ (2015) definition, Facebook, LinkedIn, games like Farmville, and the dating app Tinder would be considered social media; collaborative platforms like Wikipedia[5] and email, or a streaming platform like Netflix, would not be. Other scholars focus on identity as the central feature and purpose of social media — the presentation of one’s identity through social interaction and having an audience. Social media is also classified by the audience and functionality of its reach (Thelwall, 2009):

- socialization SNSs, used primarily for socializing with existing friends (e.g., Facebook, Instagram)

- online SNSs, decentralized and distributed computer networks where users communicate with each other through internet services

- networking SNSs, used primarily for non-social interpersonal communication (e.g., LinkedIn, a career- and employment-oriented site)

- social navigation SNSs, used primarily for helping users to find specific information or resources (e.g., Goodreads for books, Reddit)

| Social presence/Media richness | ||||

| Low | Medium | High | ||

| Self-presentation/Self-disclosure | High | Blogs | Social networking sites (e.g. Facebook) | Virtual social worlds (e.g. Second Life) |

| Low | Collaborative projects (e.g. Wikipedia) | Content communities (e.g. YouTube) | Virtual game worlds (e.g. World of Warcraft) | |

Classification of social media by social presence and self-presentation (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2020).

In his critical observation of the power of social media, Ian Bogost (2022) provides a useful history of its evolution. Data on current use is also found in this report from Pew Research.

Applications

We also refer to the “apps” that we use on our devices — downloading a new translation or mapping app when we travel, or a new real estate app when we’re looking for a new place to live. Or we upgrade current apps or software on our laptops, such as word processing programs or the learning management system used by our universities. “Apps,” also called application programs or software applications, are “computer program[s] designed to carry out a specific task other than one relating to the operation of the computer itself, typically to be used by end-users…. The other principal classifications of software are system software, relating to the operation of the computer, and utility software (‘utilities’). Applications may be bundled with the computer and its system software or published separately and may be coded as proprietary, open-source, or projects.” The software application on which you are reading this book is considered open-source — it is publicly accessible and its source code can be shared or modified.

As discussed in Truth #2, below, technology can also mean the range of devices we use to search and share electronic information, and for communications. We commonly think of our smartphones, laptops, tablets, and peripherals used along with their components (e.g, mice, monitors, speakers, microphones, headsets). But there is a wide range of device possibilities and mobilities.

#2. Our use of technology means different devices to accomplish different functions; or one device to accomplish many functions.

Our use of the internet and smartphones may seem so immediate that we can forget the purposes they serve for us. Communication is an obvious function. Just as we used landline telephones (first corded, then portable) to communicate in the past, our mobile phones enable communication with others at any time and place through voice, text, or video. Tech developers have also explored ways to make our communication more tactile, as in the haptic HugMe (Cha et al., 2008). Early mobile phones only provided ways to communicate; the smartphone revolutionized ICT by enabling touch screen access to the internet, a camera, and more.

Using devices for information is wider ranging, and we might consider types of information and subcategories. For example, while we might think of browsing the internet as an information function, using a device as a calculator or map may also be a form of gathering information (or is it a utility? Or a tool?). And some applications may offer a range of functions. Consider social media. For some, it might be a way of building social support; for others, it’s also learning more about a topic; for still others, its support, learning, and entertainment. So while we might access multiple applications on a single device like a laptop or smartphone, that device might fulfill a wide range of functions for us.

In other cases, ICT can fill very specific functions. Photography purists may prefer a separate, handheld camera to take pictures or video. A Virtual Reality headset, whether stand-alone or tethered to a personal computer, allows the user to explore an alternative landscape. Even devices that have the capability to fulfill multiple functions may be used for specific purposes. Ratliff (2014) reported that, although the smartphone was the go-to device to fulfill a range of functions, multi-device users had a preference for devices depending on function. The laptop was used to perform “work,” the tablet for entertainment, and the smartphone largely for communication and social activity. (Personal note: the author was surprised to see a family member interacting with their phone, with their laptop open, while watching a movie with other family members. They reported the easy ability to multi-task and hold multiple foci, and agreed that each device held separate functional values.)

Now consider the family, and the various devices and functions ICT provides. How might ICT help family life? Let’s translate the functions of technology into societal value, or standing in the way. What value would technology provide to the family? What challenges might it present?

Some examples:

- Communication between parent and child through texting while away at college can maintain a relationship.

- Opening a phone while eating dinner might be an intrusion. For others, it might be a way of sharing valuable information.

- During COVID, parents used computers to continue their work, as children continued participation in school. Jointly, they used videoconferencing technology to maintain connections with extended family.

- A new parent may search for available, affordable, and quality child care for his infant twins.

Now think beyond the traditional family, or the family best known to you. Consider families you read about in the news or relatives in distant countries. In the current conflict in Ukraine, for example, how might using cell phones fulfill valuable functions for families in the country or who have immigrated? Would seeing images of the destruction be useful or, for children using TikTok, create stress?

Understanding technology’s range of functions, and our use of devices to fulfill those functions, can give us a basic way of conceptualizing the processes that contribute to individual, family, and societal outcomes.

#3. Our use of technology has changed dramatically over a short time.

Internet availability

At the beginning of the chapter, we discussed how technology and university life have changed in last 50 years. In fact, the efficiencies offered by ICT have really only existed since the web was introduced in 1991. As the internet became available, the rates of people accessing it and using it increased rapidly. Pew reports that in 1994, 18% of people used the internet. In 2021, that percentage was 93%, ranging from 99% of those 18–29 years old to 75% of those 65 and older. As a different metric, the current population of persons using web browsers is nearly 5 billion (4,878,428,571) — 62% of the world’s population. Web 2.0 technology moved us from one-way communication in web pages and email to interactive, collaborative, social tools with blogs, wikis, social networking, mobile/handheld devices, and more.

Shifts in behavior

As Lee and Cooper observe in Endgadget, since 2004 (the last 15–20 years), we’ve become able to:

- Hold the world in our hands via smartphones (which debuted in 2007).

- Capture everything through cameras on the phone. (This capability also added the word “selfie” to conventional dictionaries.)

- Effortlessly track our movements through smartwatches and other devices that send information about our health.

- Navigate maps on our phones

- Step into another world through Virtual Reality, and now Augmented Reality.

- See, listen, and play everything in seconds (through Netflix, Hulu and lots of other streaming services).

- Connect to everyone. Yes, social media like MySpace and Friendster existed before 2004, but it wasn’t until Facebook entered the marketplace in 2006 that things really took off.

- Create anything (as long as it is small and plastic) using 3D printers.

- Use an affordable, mobile option for computing and for reading, thanks to tablets and e-readers with touchscreens.

- Speak, and have it done — through voice-activated assistants and smart speakers, and also through smart devices like doorbells, lights, and thermostats.

- Ask the world for patronage or support, with sites like Kickstarter making it easy to click a button and collect/donate funds.

- Share everything, like cab rides through an app that finds a driver for you.

- Drive electric cars.

The rapid advancement of information and communications technology in the last 20 years has also revolutionized our way of thinking and living. Beyond making life more efficient, the internet offers an additional environment for interaction and engagement. We can operate IRL (in real life) and virtually. As Alicia Blum-Ross describes it, the internet is like wallpaper; it always seems to be there. Our comfort with access to information and people anytime, anywhere can leave us feeling bewildered (FOMO?) when we’re without service.

Visual Capitalist offers a slick graphic, below, of the history and rise in use of media. Early media, starting in the 15th century and going through the end of the 20th century, includes telephones, newspaper, and television. While these media can be used to spread information to the masses, they are also one-way, leaving the power of the content in the hands of the creator. The second wave — Connected Media — spans from 2000 to 2020, with the inclusion of the smartphone. Media is now two-way, and engagement is everything. Yet explosive use and easy access also means “fake news,” censoring, and surveillance. The Data Media phase, which we are now in, offers access to primary data sources for information and the ability to verify. However, this can also mean “cherry picking” (selecting data to prove a point or to slant the narrative) and the temptation to falsify data. Looking ahead, we will see more creative and constructive ways to use data, and further de-centralization.

And there is much ahead. In 2021, reflecting on COVID-19, Brian Chen in the New York Times wrote about augmented reality for our shopping experiences, which will allow us to try things on or see what things look like in our homes before buying, and “hands-off” technology that will read our smartphones, making it unnecessary to access payment apps. He joins the ranks of technology futurists who predict our lives in decades, even just years to come.

Device ownership

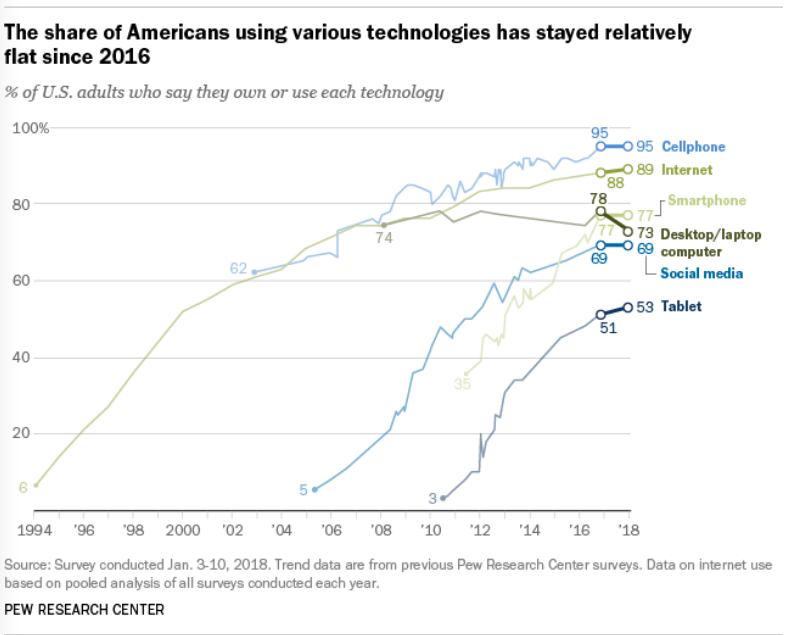

Pew (Hitlin, 2018) reports on the rapid rise in technology use after 1994, noting that figures have plateaued since 2016. It is interesting that the desktop/laptop computer is the only technology showing a significant decline.

Social media — growth and impact

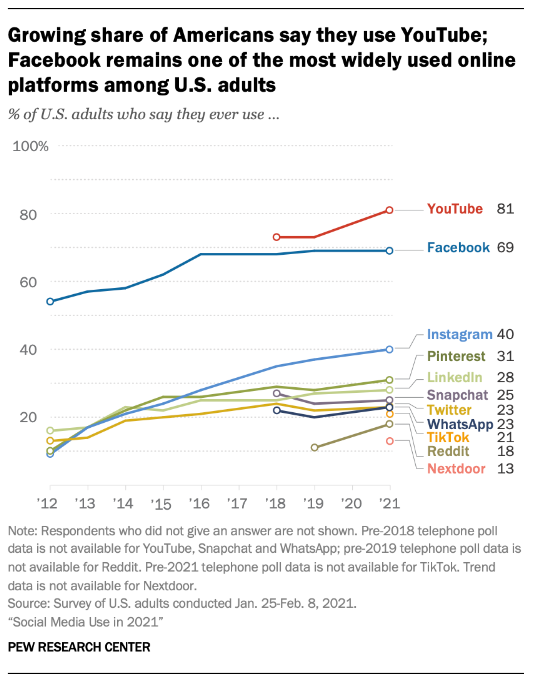

Pew Research (Auxier & Anderson, 2021) reported that, in 2021, approximately two-thirds of Americans used some kindof social media, and illustrated shifts in the use of various social media platforms, below Among teens, platform use is different (Vogels et al., 2022). TikTok, for example, is used by 67% of those ages 13–18, and Instagram by 62%, whereas Facebook consumption is much lower than general U.S. figures, used by only 32% of teens. As indicated by the figure below, use has increased over time for some platforms like Facebook and Instagram and remained relatively steady, such as with Twitter.

Beyond the power of the internet to invite interaction and engagement, social media enables us to quickly make social connections, expand the size and shape of our networks with others, and quickly share and receive information In Here Comes Everybody, Clay Shirky, an early writer on the power of social technologies, observes that social media holds the power to expand the size and shape of our social networks by connecting our more intimate social worlds with those of others. This diversifies our contacts, nd offers us access to a flow of information, and strengthens our social connections. This clip from the 2018 film Crazy Rich Asians depicts the speed of sharing information across social connections.

One aspect of information speed relates to news events. The author was in Washington D.C. on September 11, 2001. We first heard about the planes crashing into the towers, and then into the Pentagon, through radio and

television. For the rest of the day we were dependent on these sources — and on constantly refreshed news webpages — to get updated information. The delivery of news was slow and controlled by others. We had less personal involvement in it.

By 2013, the rapid spread of information from a news event — a shooting at the Washington Navy Yard on September 16 at 8:20 am— prompted within 30 minutes a public response through Tweets, Reddit posts, live video footage, “I’m fine” posts, crowdsourcing information to help with the investigation (quickly taken down), and a Facebook memorial page. This isn’t surprising to us today. Events are live-streamed; Philando Castille’s girlfriend, for example, posted a video on Facebook of his murder in 2016 as it happened. And when events are anticipated — like Hurricane Ida, which hit Louisiana in the fall of 2021, Facebook pages are set up in advance so victims can indicate their status.

What does it mean to have the ability to engage and share information so quickly? Consider this from a family perspective. What are the benefits? Might there be any consequences? When information spreads quickly there can be mistakes, which can get in the way of professional reporting and can breed a certain impatience. A colleague from Louisiana related that there was such an assumption that people would turn to Facebook during the hurricane, that people ignored the likely scenario of internet service being unavailable during the disaster.

Using social media data, new research is measuring the power of social connections on outcomes such as economic success (Chetty et al., 2022). Researchers are employing social capital data from over 21 billion Facebook “friendships” to determine social connectedness, social cohesion, and predictors of economic well-being. An advantage to the rise and steady use of social media lies with the volumes of data that, as in this case, can be used to infer social well-being. On the other hand, public sites like Facebook and Instagram are well-known for leaking personal information and exposing users to security breaches. For this reason, numerous sites provide recommendations on how to keep social media accounts safer (e.g., Kelly & Fowler, 2021).

#4. Our use of technology varies.

Although the numbers indicate that technology use is prolific, within that data individuals vary in their access, use, skills, and attitudes. Consider the people you interact with regularly — your family, friends; at school, home, and work. It is very likely that you use social media apps differently than your parents, and that your parents use technology for work differently than you use it for school and work. Your younger sibling may be a “gamer,” while you spend more time on your laptop writing papers for school. Your family home may be outfitted with smart speakers; your apartment may be lucky to get a strong wifi signal. You may use a multitude of devices, while your cousin in Ghana lives only on her smartphone.

It matters that we understand differences in use. As we’ll discuss in our next “truth,” and more in Chapter 3, because ICTs are used for communication, differences in behavior can create disruptions in the flow of communication, which can lead to conflict. Because ICTs are used to find and share information, behavioral differences can affect relationships if, for example, personal information about one person is shared by another. And because people vary in their access to ICT, they vary in their ability to communicate, share and find information, and benefit (or be negatively affected) from the functions ICT enables. We’ve observed differences in technology use over time, and differences in which platforms are popular for social media use.

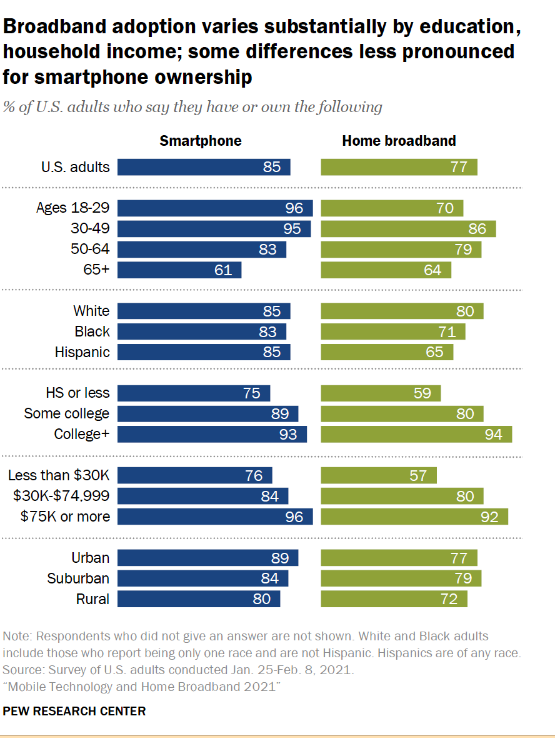

Demographics — broad factors used to characterize individuals in a population — are easy to access to describe differences in technology use. The chart below, from the Pew Research Center, illustrates differences in smartphone ownership and broadband use by age, race, education, income, and geography. Although overall numbers indicate that 85% of people have smartphones and 77% report broadband access at home, there are differences by groups. Fewer older Americans, those with less education and income, and those living in rural areas report both; more Whites than people of other races report broadband access.

And naturally, individuals don’t exist by a single characteristic. Often there are correlations between education and income; between education, income and geography; between race, education, income, and geography. (APA, 2017) So if we read that Hispanic women are less likely to have internet access, is that because they are Hispanic, or because they are likely to be in an income category that challenges their ability to purchase internet? Or because they are likely they live in a rural area that doesn’t provide high-speed internet? Internet access isn’t always tied to individual income; it is tied to economic infrastructures that make internet service available.

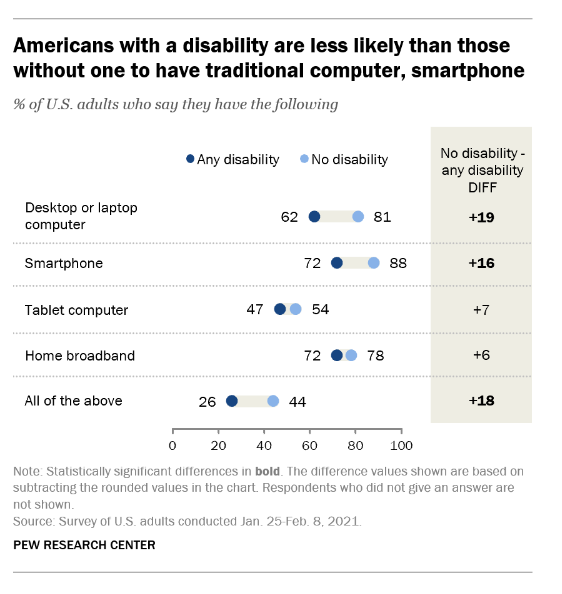

It’s also possible that lack of internet access is due to preference. The Pew report observes that, while many of those without broadband access mention its cost or availability, others use their smartphones for the internet or simply prefer not to have it. Pew also reported that, in 2021, those with disabilities were less likely to have some devices, own multiple devices, and have access to broadband (Perrin & Atske, 2021).

Technology use also varies by preference, attitude, and comfort. We’ve observed that social media has become more popular over the last decade among all age groups, though younger groups show the highest use, and that platform preferences have shifted. YouTube and Instagram are frequented more than Pinterest and Twitter. Consistent increases in social media use are also revealed across race, gender, education, income, and geographic location (e.g., rural, suburban, urban). Use differs little by race and gender, but slightly more by income and by education. Age differences may represent generational perspectives, which can reflect exposure to trends and to events that shape attitudes. For example, this piece discusses differences in perspectives of Millennials and Gen Z.

Within a group of “users,” there are differences in behavior. Among Twitter account holders, there are clearly high- and low-volume consumers (McClain, et al., 2021), and portion of the high-volume users account for the majority of the content we read: “An analysis of tweets by this representative sample of U.S. adult Twitter users from June 12 to Sept. 12, 2021, finds that the most active 25% of U.S. adults on Twitter by tweet volume produced 97% of all tweets from these users.” The report identifies differences in attitudes among users by volume, with those posting often feeling their political views influenced and more likely to experience harassment. Ironically, however, these users are less likely to view the atmosphere as a problem. We might consider those high-volume Twitter posters as a “type,” and we wouldn’t be alone. A significant line of research on internet and technology consumption analyzes the behavior and preferences of users (e.g., Blank, & Groselj, 2014; Borg & Smith, 2018). Why would this be of interest?

#5. Variation in use and access can mean new sorts of divides.

With the COVID-19 pandemic requiring children to stay home from school, significant divides in access to technology had consequences on school attendance, participation, and learning. Even if schools loaned wifi hubs, Chromebooks, or other devices that enabled children to attend school at a distance, their homes were not necessarily equipped with internet access. Those families with devices may have had to share a single screen. And if parents were working from home, priority may have gone to adult employment over children’s engagement in classes. In Chapter 3 we’ll explore more about access differences in the U.S. and around the world. As an example of global differences in technology access and children’s learning, Ayllon et al (2021) show high European Union country variation by households without access to a computer and households without access to the internet during COVID-19.

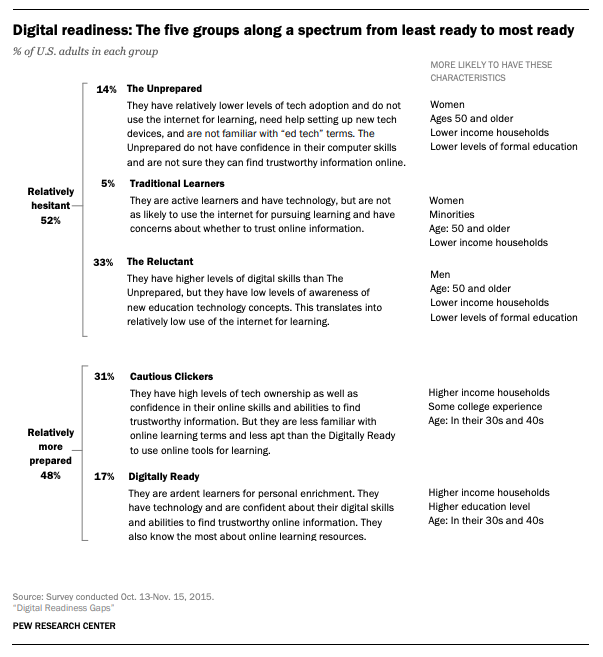

Variations in access can also mean variations in “readiness.” Those with less ability to use technology become less skilled and comfortable and may develop attitudes that lean toward not using it, or not using particular applications (think, for example, of a grandparent’s interest in joining Instagram). In 2016 Pew identified a “readiness gap: among internet users (Horrigan, 2016). As we can see in Figure 5, below, there are demographic differences in those who are “unprepared” and those who are “ready,” with correlations once again to income, education, and age.

Differences in access can also mean divides in who influences others’ behavior. One example is political values and voting behavior. This interactive chart reveals shifts in ideologically political values and partisanship from 1994 to 2017. We can correlate this shift with the growth in ICT availability and use of smartphones, which made access to social media easier. And social media has the power to influence global politics, like the May 2022 presidential election in the Philippines. Politics isn’t the only thing influencing those who actively use social media; “Grandfluencers” on TikTok, for example, are attempting to shift our perceptions of aging.

#6. Our technology use presents a paradox: as it offers many benefits, it equally poses challenges.

In 2005, Javenpaa and Lang’s research on mobile technology experiences identified eight paradoxes in use:

- Empowerment / enslavement: our access to information and others 24/7, yet exposure to those we’d rather not see, and our access to functions, which in turn encourages our availability.

- Independence / dependence: use of our devices to make life easier, yet creates a dependence on those devices to make our lives easier.

- Fulfills needs / creates needs: new technology provides valuable functions, yet it creates costs and needs for management.

- Competence / incompetence: as people gain new skills in using technology, they also have another area of life in which to feel competent / incompetent.

- Planning / improvisation: devices make planning more efficient, yet some users put less effort into planning, leaving it to an “app” and thus losing skills and leaning on improvisation.’

- Engaging / disengaging: the ability to engage with others is enhanced, yet equal engagement across exposure is impossible, which leaves some connections “disengaged” (see “phubbing”).

- Public / private: technology enables private communication, yet it increasingly enters the public domain.

- Illusion / disillusion: users believe that tech will make their lives easier, which is often true, yet they also can experience disillusionment when it doesn’t work as well as they’d hoped.

We’ll see these paradoxes and others played out in the many examples and research findings offered in this book. Future chapters will explore how technology can bring families together, while differences in use can also threaten understanding and closeness, challenging feelings of connectedness. Technology can aid children’s creativity and learning, yet at the cost of introducing sedentary habits acquired through excessive hours of screen time. It can offer adolescents opportunities to create important friendships, yet the public nature of these conversations can have damaging effects. An episode of This Hidden Brain, for example, features an interview with a young man who was accepted to a prestigious university. The university offered a Facebook group for incoming freshmen to help them get acquainted and feel connected to others when starting school. The group discussion included some rather “casual” language that encouraged users to be less cautious with what was said. For the young man interviewed, this included some racial slurs. Because the forum was moderated, admissions staff read and carefully considered the discussion, resulting in several of the students being un-invited. Many have experienced harsh lessons like this — though perhaps to lesser consequence — by taking advantage of the social media’s connectivity benefits yet being reminded of the public, shareable, and viewable nature of the words.

Here are just a few more benefits and complementary consequences of our lives online:

- Texting is an easy, mobile way to get and send information, YET the availability of our mobile phone numbers exposes us to “smishing” campaigns (AKA spam texts).

- Using smartphones is convenient, yet some phones can expose to unhealthy levels of radiation.

- Zoom is great for video conferencing with friends and family, for work, and for communication with professionals like doctors and therapists, yet over time, our energy gets drained from using this medium.

- Banking and shopping are incredibly convenient from the comfort of our couches, but essential information can be compromised, and we become a “data security” statistic.

#7. Our use of technology as individuals affects others; others affect our technology use.

Our information and communications technology is often referred to as “personal” technology — we use it as individuals for individual purposes. Yet given that the internet is a system of networked servers that allow users to easily share information, it is likely that our use can affect others, intentionally or unintentionally. We might also think about the settings in which we use personal technology. If you’ve ever been annoyed by someone having a loud conversation on their phone in a public place, you’ve been affected by another’s “personal” use. And if you stray from taking lecture notes on your laptop and start shopping on Amazon during class, the students behind you may be distracted by your screen. If you find “spam” in your inbox, the sender has influenced your technology experience.

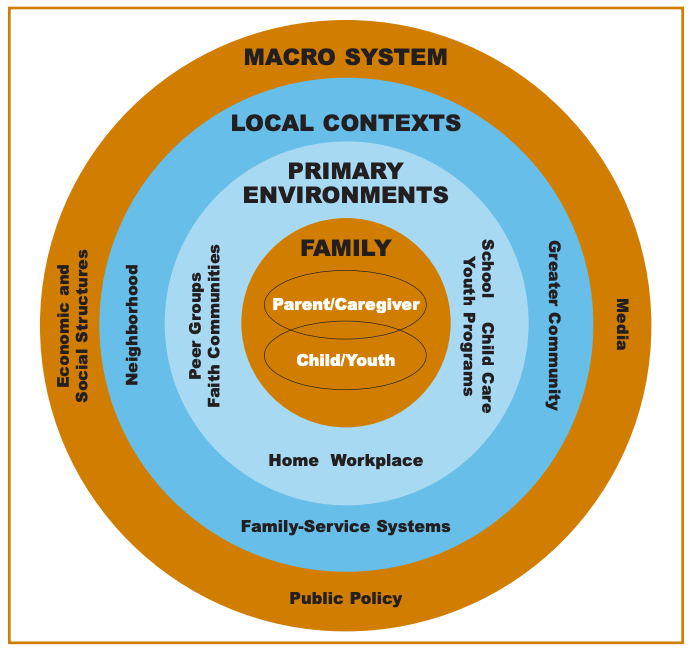

In the next chapter, we’ll look more closely at a model of human development that contextualizes the settings and conditions in which human beings thrive as influences on their development. Urie Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological perspective of human development (1995) identifies development as the result of individual biology in interaction with settings (including the people and events in them) over time. Those settings can be both proximal and distal to us in location and interaction frequency. For example, those closest to us — our family and friends, people at our workplaces and our schools — are those we interact with often. And it isn’t unusual for those settings to interact — when our parents and teachers meet, or when we carry stress from the workplace to our home-based relationships. And still wider or distal influences come from the institutions, government policies, cultures, and societies we are part of. They have an indirect influence on us, often through messages repeated by our nearby contacts. The model depicted below adapts Bronfenbrenner’s classic framework perspective to include subsystems of the family, including parents and children, and contexts, including family service systems and government policies.

A neo-technological modification of this model by Navarro and Tudge (2022, discussed in Chapters 2 and 5) proposes the internet as an environment for interaction parallel to real life. We can imagine how a teen’s cyber harassment experiences might result in feelings of stress and anxiety that others offline (like her family or friends at school) can see, respond to with support, or potentially exacerbate.

At a macro level, we appreciate the role that policies and regulations can have on our experiences with technology. As previously noted, data from our time online is easily shared, and our privacy and security can be compromised. One result is the creation of policies to protect users, particularly young ones. For example, the 2020 California Children’s Privacy Act provides more stringent protections than COPPA (Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act) related to notice and consent, children’s rights, enforcement, and other items. It is similar to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe. On the other hand, whole governments like China seize control of the internet to limit the extent to which individuals can post, and what they can see. In other words, these government censor the internet.

#8. The effects of technology can seem out of our control.

China’s censorship is a perfect example of how individuals can feel that the effects of technology are out of their control. If we are limited in what we attempt to see and read, to post and participate in, we feel powerless in our engagement and thus in the effects we experience. We learn how TikTok algorithms determine the content we see. And news of the ways in which our data is not private when we interact with ICT can leave us feeling powerless. Recent examples include data tracking from baby monitors, Facebook revealing data on those seeking an abortion, and data pulled from a phone that led to a priest’s resignation. Tufecki (2019) warns that algorithms and analysis from network data provide inferences about many things that are never disclosed, including individuals’ sexual orientation and moods. She notes that apps as innocuous as those for weather updates were found to sell users’ location data, which was used to make inferences (“What were you doing at a cancer clinic?”).

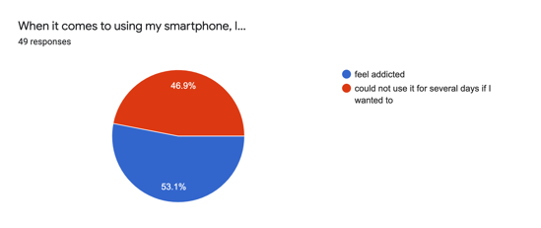

Related to our list of paradoxes, above, although we can love using technology we can also feel addicted to it. Every semester students in FSOS 3105 are asked if they feel addicted to their smartphones. Here are the results from fall 2021 (which are quite similar to those from other semesters between 2017 and 2022).

Yet is our addiction the result of our own conscious behavior? As Tiku observes, ICT is programmed in ways that keep us interested and glued to it, generating FOMO (the fear of missing out). These methods include push notifications, pull-to-refresh, infinite scroll, autoplay, bright colors, streaks (or short-term goals), and gamification using points, a leaderboard, and rewards. Atler (2017) also investigates how applications are programmed to keep our attention, and observes that our attention span has decreased an average of 8 seconds since the introduction of iPhones. The website VirtualCapitalist.com identifies 33 ways that media can be a problem for its users.

With these industry-created, subconscious methods of encouraging us to keep using technology, and our data being used in ways we aren’t aware of (despite the prevalence of pop-ups on websites asking us to “agree” on a privacy policy or use of cookies), it can feel like we’re powerless. In large part, awareness can help (see Truth #10), as can action to keep our technology use limited and intentional. And we can advocate for stricter protections from the very people we pay to make our lives easier, and from our governments.

#9a. We are in the very early stages of understanding information technology’s impacts on us as individuals and as a society.

#9b. Continual innovation in ICT will challenge our ability to do research that informs practice and policy.

During COVID-19, our initial months of quarantine were our best protection from the virus. We waited for a vaccine to protect us from contracting the disease. This meant waiting for the testing and approvals through the Food and Drug Administration. Even “fast-tracked,” this process involves panels of experts reviewing research that shows evidence of product development and testing, clinical trials, testing for side effects, effectiveness, and large-scale success. Part of that review is ensuring that the research was rigorous and followed a strict protocol, with conditions controlled so as not to introduce any confounding variables that would pose alternative explanations for the findings.

In the case of ICT, in most cases there isn’t a treatment to eradicate a problem (though its applications can facilitate treatment). Instead, there is a range of products, including the internet as a virtual environment for information and communication interaction. Still, as with any product we use, we want to know that it is both safe and effective. Product testing of devices such as smartphones for radiation exists. Yet when it comes to the effects of using the products for communication, information gathering, sharing, and creating uses, and to our questions about their effectiveness and impact on aspects of human development, learning, and family life, we have moved to other realms of “knowing.” There are many ways of “knowing.” Jhangiani et al., in Research Methods in Psychology, identify these five:

- Intuition, or our “gut” response to an experience,

- Authority, or relying on the words of another, authoritative guide,

- Rationalism, or applying reason and logic to understanding a phenomenon,

- Empiricism, or making an observation from experience, and

- The Scientific Method, or “the process of systematically collecting and evaluating evidence to test ideas and answer questions.”

Consider what you “know” about the safety and effectiveness of using a smartphone. Or what we “know” about teenagers feeling depressed from scrolling Instagram. And how we know it. Is our knowledge based on personal experience or observations, or from reading a compilation of research findings? Did the research include users like YOU? Was the research on adolescents short-term, measuring depression at a single point in time, or did it follow them to see if the symptoms changed?

The challenge with the relative novelty of information and communications technology is that we’re still in the early stages of using the devices and applications. And with major events like COVID-19, we’re using them under ever-changing circumstances. As Martha Pickerell observed in 2015, and which still rings true to an extent,

There is no reliable evidence yet of long-term risks from overexposure to screens. The current guidelines for kids’ use of screen media are based on decades of research into kids’ TV habits and the related outcomes: poorer performance in reading and language arts, lower attention span, and higher risk of obesity among kids who watched excessively.

We have more research on the effect of screen exposure — both the quality of exposure and the quantity of time — on children at different ages in different sets of conditions, but it’s not longitudinal, and doesn’t have the volume of the research on TV viewing, which had a good 40–50 years before the advent of personal computers, tablets, and mobile devices.

Look at the two images below, of children viewing a television (left) and a computer (right). Can we apply what we know about television viewing to our use of modern ICT? Think about the differences between viewing a TV screen and interacting with a computer; one with internet access and that runs a range of software. Would research on their impacts by the same? How would it be different? Changes in television — in size, color display, and content offerings — haven’t been at the speed of changes in our mobile devices, applications, algorithms, and internet capabilities. The research-to-publication pipeline moves relatively slowly for all the points of rigor along the way. Yet in that time, what we use and how we use it can change dramatically. Colleagues of the author gathered data on parents’ interactions on discussion forums, which became outmoded when social media took over.

In the meantime….

- “Watching TV” by oddharmonic is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

- “Children using the library computers.” by San José Public Library is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

#10. Our “intentional” use is a way for ICT to be both safe and effective for us and in our responsibility to others.

While we may be the guinea pigs in using ICT, and subject to the ongoing findings of researchers, we accept that our use brings certain benefits and that we will remain open to understanding the risks. Parents report that it’s harder to parent today than ever before, and technology is the reason cited by most (Auxier et al., 2020). Yet they don’t forbid their children, or themselves, from using it. They practice ways of knowing, whether through observation and action, trusting an authority figure, or open conversation with their children. danah boyd, ICT pioneer, philosopher, and parent (Tippet, 2017), remarked:

I think that it’s a tool. It’s a vice for some. It’s a way of connecting. There’s all of these different layers to it. And we’ve had to think about how to be responsible in relationship to anything. If you think about it in terms of ancient religious texts, you think about gluttony, think about what is our relationship to food. We agree that food is a necessity, but what’s the level in which it’s acceptable? … Like all of these other stimuli, though, we should step back and say, hey, what is the relationship I want to have with people, with food, with substances, with the internet, with my environment? And that’s where I do think that there’s a spiritual ask to all of this.

The idea of intentionality can seem very hard, particularly for Millennials and Generation Z’ers, who grew up with the internet, mobile devices, and social media. Yet we are all becoming aware of our reliance on smartphones — and of their possible impact on our personal, in-person conversations, of the feelings of being addicted to them, and of how we respond to the discomfort of feeling bored or impatient by giving in to the impulse to check for messages or scroll for updates.

We can practice what Michelle Drouin calls “social economizing,” making active decisions about how we want to spend our time — alone, with others, on technology or not — and taking steps to realize our intentions. And we can check our security settings on streaming devices to reduce tracking when we watch Euphoria or the Bachelorette.

This is where family professionals come in. Not only are they researching technology’s effects, but those on the front lines as educators and service providers help families get the information they need to make informed decisions — the reason for this book) And information about technology is best consumed with a critical eye — another reason for this book. As mentioned earlier, while our use can seem personal, it can have clear impacts on others. We can enjoy a new app, yet realize that it’s sharing personal data in a way we find objectionable. Our use must be ethical and responsible, and seeing the complexity of our technology use as individuals, as family members, as professionals, and as a global society is key.

We can challenge technology innovators to be wise to the intended and unintended effects of their products. In her On Tech column in the New York Times, Shira Ovide cautioned against building new tech like augmented reality. While such technology can seem like a fun way to experience new places and adventures, we must consider other uses and pre-consider the possible risks. She asked about AR (augmented reality):

What do we want from the next generation of immersive internet for our kids? Do we want to drive while our headgear flings tweets into our fields of vision? Do we even want to erase the gap between digital life and real life?

When we think about the future — and think beyond ourselves to our near and far communities — our technology use can become part of the common good. Several years ago, Kevin Kelly, a co-founder of Wired magazine, described the Amish community’s interest in ICT. Well-known for their religious practices, which shun the use of electricity and other technologies, the Amish did not immediately dismiss the notion of cell phones. Rather, they deployed several of their younger members to use the phones for several weeks to test their purpose and the value they’d bring to the group. Their interest was to identify any potential value for the community.

Our awareness of technology’s impact and use by families begins with our careful reflection on the ways in which we use technology in our own lives, how it affects our relationships and communication, how it enhances and detracts, and what it might mean in the future. This is a big ask — and I appreciate your joining me on this journey.

- Throughout the book the coronovirus of 2019 will be spelled COVID-19 or Covid-19 as there doesn't appear to be an agreed upon convention on capitalization of this disease ↵

- On the other hand, the accepted spelling of internet is internet (not Internet) and this will be consistently followed through the book. ↵

- Readers are strongly encouraged to follow the Wikipedia link to read more about the internet, its scope, history, and governance ↵

- Readers are directed to the Wikipedia page for the World Wide Web for detailed descriptions of common terms like browsers, servers, cache, and cookies. ↵

- Although in a recent interview, Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales talked of the challenges with page editing by those with an agenda. ↵