8.4 Diversification Strategies

Learning Objectives

- Explain the concept of diversification.

- Be able to apply the three tests for diversification.

- Distinguish related and unrelated diversification.

Firms using diversification strategies enter entirely new industries. While vertical integration involves a firm moving into a new part of a value chain that it is already is within, diversification requires moving into new value chains. Many firms accomplish this through a merger or an acquisition, while others expand into new industries without the involvement of another firm.

Three Tests for Diversification

A proposed diversification move should pass three tests or it should be rejected (Porter, 1987).

- How attractive is the industry that a firm is considering entering? Unless the industry has strong profit potential, entering it may be very risky.

- How much will it cost to enter the industry? Executives need to be sure that their firm can recoup the expenses that it absorbs in order to diversify. When Philip Morris bought 7Up in the late 1970s, it paid four times what 7Up was actually worth. Making up these costs proved to be impossible and 7Up was sold in 1986.

- Will the new unit and the firm be better off? Unless one side or the other gains a competitive advantage, diversification should be avoided. In the case of Philip Morris and 7Up, for example, neither side benefited significantly from joining together.

Related Diversification

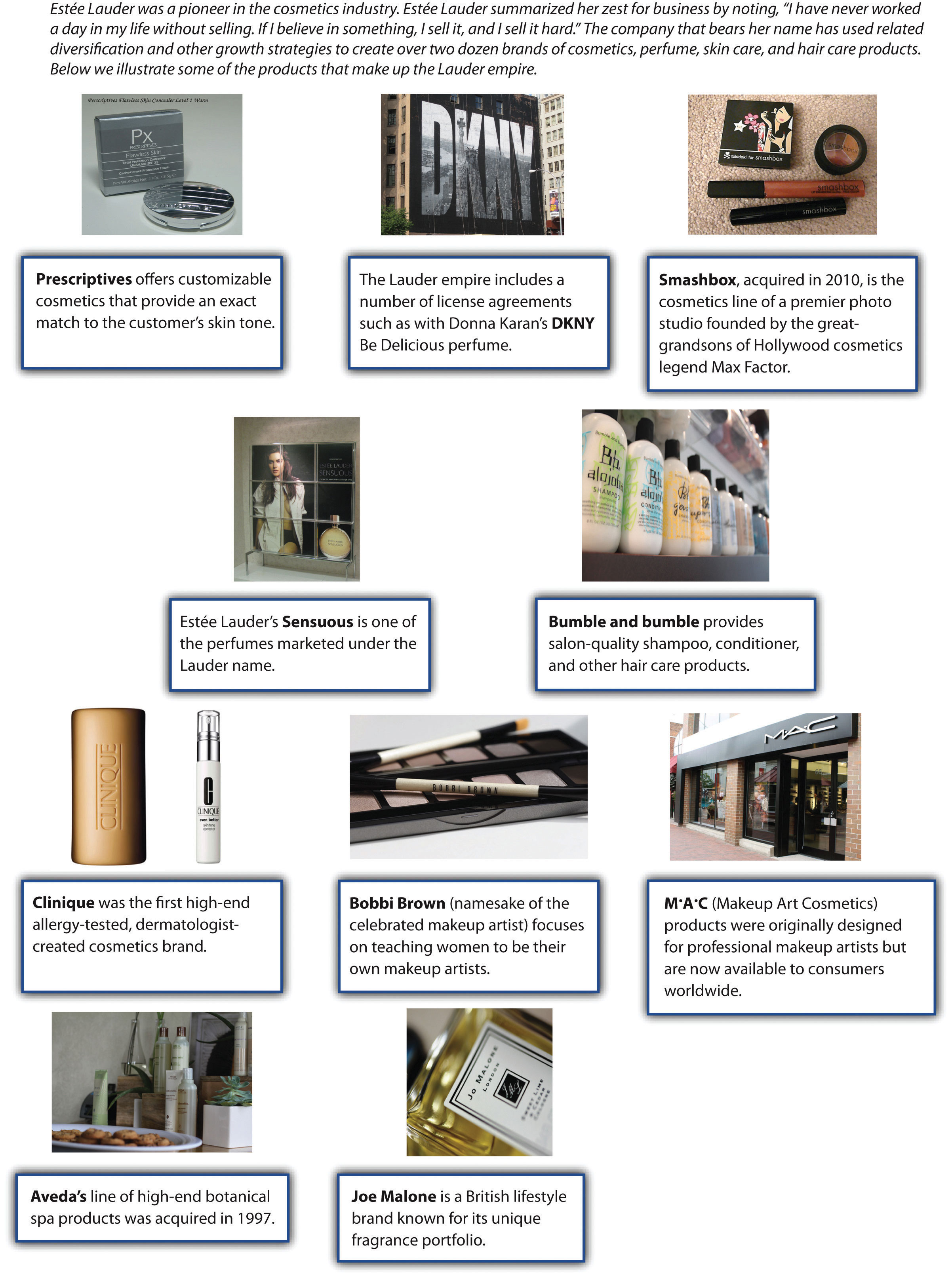

Related diversification occurs when a firm moves into a new industry that has important similarities with the firm’s existing industry or industries (Figure 8.4 “The Sweet Fragrance of Success: The Brands That “Make Up” the Lauder Empire”). Because films and television are both aspects of entertainment, Disney’s purchase of ABC is an example of related diversification. Some firms that engage in related diversification aim to develop and exploit a core competency to become more successful. A core competency is a skill set that is difficult for competitors to imitate, can be leveraged in different businesses, and contributes to the benefits enjoyed by customers within each business (Prahalad & Hamel, 1990). For example, Newell Rubbermaid is skilled at identifying underperforming brands and integrating them into their three business groups: (1) home and family, (2) office products, and (3) tools, hardware, and commercial products.

Figure 8.4 The Sweet Fragrance of Success: The Brands That “Make Up” the Lauder Empire

Betsy Weber – Aveda Suite – EVO Conference – CC BY 2.0; ookikioo – Bobi Brown Stonewashed Nudes Palette – CC BY 2.0; Shortcuts Smarter Business Technology – Studio DNA – Bumble and bumble – CC BY 2.0; Joanne Saige Lee – facial soap – CC BY 2.0; Joanne Saige Lee – ’even better’ skin tone corrector – CC BY 2.0; Jessica Sheridan – DKNY_060309_2514 – CC BY 2.0; David Fulmer – Estee Lauder Sensuous – CC BY 2.0; Mohmed Althani – Jo Malone Perfume – CC BY 2.0; Church Street Marketplace – MAC Cosmetics – CC BY 2.0; ookikioo – Prescriptives Flawless Skin Concealer – CC BY 2.0; porcupiny – Tokidoki for Smashbox cosmetics – CC BY 2.0.

Honda Motor Company provides a good example of leveraging a core competency through related diversification. Although Honda is best known for its cars and trucks, the company actually started out in the motorcycle business. Through competing in this business, Honda developed a unique ability to build small and reliable engines. When executives decided to diversify into the automobile industry, Honda was successful in part because it leveraged this ability within its new business. Honda also applied its engine-building skills in the all-terrain vehicle, lawn mower, and boat motor industries.

Honda’s related diversification strategy has taken the firm into several businesses, including boat motors.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Sometimes the benefits of related diversification that executives hope to enjoy are never achieved. Both soft drinks and cigarettes are products that consumers do not need. Companies must convince consumers to buy these products through marketing activities such as branding and advertising. Thus, on the surface, the acquisition of 7Up by Philip Morris seemed to offer the potential for Philip Morris to take its existing marketing skills and apply them within a new industry. Unfortunately, the possible benefits to 7Up never materialized.

Unrelated Diversification

Table 8.5 Unrelated Diversification at Berkshire Hathaway

”Don’t put all your eggs in one basket” is often a good motto for individual investors. By building a portfolio of stocks, an investor can minimize the chances of suffering a huge loss. Some executives take a similar approach. Rather than trying to develop synergy across businesses, they seek greater financial stability for their firms by owning an array of companies. Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway has long enjoyed strong performance by purchasing companies and improving how they are run. Below we illustrate some of the different groups in their very diversified portfolio of firms.

| Berkshire’s insurance group includes firms such as General Re and GEICO. They maintain capital strength at exceptionally high levels, which gives them an advantage even a cave man could understand. | Berkshire’s financial health is also fueled by utilities and energy companies that are part of the MidAmerican Energy Holdings Company. | Their apparel businesses include well-known names such as Fruit of the Loom and Justin Brands. |

| Building companies include Acme Building Brands, makes of the famous brick, as well as paint company Benjamin Moore & Co. | FlightSafety International Inc. is a Berkshire firm that engages in high-tech training to aircraft and ship operators. | Retail holdings include a number of furniture businesses such as R.C. Willey Home Furnishings, Star Furniture Company, and Jordan’s Furniture, Inc. |

|

Hungry for more businesses to manage, Berkshire acquired The Pampered Chef, Ltd.—the largest direct kitchen tools seller—in 2002. |

Buffett had a sweet tooth for See’s Candies, who he purchased from the See’s family in 1972. |

Shareholders were all on board for the purchase of the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Corporation in 2009. |

Why would a soft-drink company buy a movie studio? It’s hard to imagine the logic behind such a move, but Coca-Cola did just this when it purchased Columbia Pictures in 1982 for $750 million. This is a good example of unrelated diversification, which occurs when a firm enters an industry that lacks any important similarities with the firm’s existing industry or industries (Table 8.5 “Unrelated Diversification at Berkshire Hathaway”). Luckily for Coca-Cola, its investment paid off—Columbia was sold to Sony for $3.4 billion just seven years later.

Most unrelated diversification efforts, however, do not have happy endings. Harley-Davidson, for example, once tried to sell Harley-branded bottled water. Starbucks tried to diversify into offering Starbucks-branded furniture. Both efforts were disasters. Although Harley-Davidson and Starbucks both enjoy iconic brands, these strategic resources simply did not transfer effectively to the bottled water and furniture businesses.

Lighter firm Zippo is currently trying to avoid this scenario. According to CEO Geoffrey Booth, the Zippo is viewed by consumers as a “rugged, durable, made in America, iconic” brand (Townhall, 2010). This brand has fueled eighty years of success for the firm. But the future of the lighter business is bleak. Zippo executives expect to sell about 12 million lighters this year, which is a 50 percent decline from Zippo’s sales levels in the 1990s. This downward trend is likely to continue as smoking becomes less and less attractive in many countries. To save their company, Zippo executives want to diversify.

The durability of Zippo’s products is illustrated by this lighter, which still works despite being made in 1968.

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 2.5.

In particular, Zippo wants to follow a path blazed by Eddie Bauer and Victorinox Swiss Army Brands Inc. The rugged outdoors image of Eddie Bauer’s clothing brand has been used effectively to sell sport utility vehicles made by Ford. The high-quality image of Swiss Army knives has been used to sell Swiss Army–branded luggage and watches. As of March 2011, Zippo was examining a wide variety of markets where their brand could be leveraged, including watches, clothing, wallets, pens, liquor flasks, outdoor hand warmers, playing cards, gas grills, and cologne. Trying to figure out which of these diversification options would be winners, such as the Eddie Bauer-edition Ford Explorer, and which would be losers, such as Harley-branded bottled water, was a key challenge facing Zippo executives.

Strategy at the Movies

In Good Company

What do Techline cell phones, Sports America magazine, and Crispity Crunch cereals have in common? Not much, but that did not stop Globodyne from buying each of these companies in its quest for synergy in the 2004 movie In Good Company. Executive Carter Duryea was excited when his employer Globodyne purchased Waterman Publishing, the owner of Sports America magazine. The acquisition landed him a big promotion and increased his salary to “Porsche-leasing” size.

Synergy is created when two or more businesses produce benefits together that could not be produced separately. While Duryea was confident that a cross-promotional strategy between his advertising division and the other units within the Globodyne universe was a slam-dunk, Waterman employee Dan Foreman saw little congruence between advertisements in Sports America on the one hand and cell phones and breakfast cereals on the other. Despite his considerable efforts, Duryea was unable to increase ad pages in Sports America because the unrelated nature of Globodyne’s other business units inhibited his strategy of creating synergy. Seeing little value in owning a failing publishing company, Globodyne promptly sold the division to another conglomerate. After the sale, the executives that had been rewarded for the initial purchase of Waterman Publishing, including Duryea, were fired.

Globodyne’s inability to successfully manage Waterman Publishing illustrates the difficulties associated with unrelated diversification. While buying companies outside a parent company’s core competencies can increase the size of the company and in turn its executives’ bank accounts, managing firms unfamiliar to management is generally a risky and losing proposition. Decades of research on strategic management suggest that when firms diversify, it is best to “stick to the knitting.” That is, stay with businesses executives are familiar with and avoid moving into ventures where little expertise exists.

In Good Company starred Topher Grace as ill-fated junior executive Carter Duryea.

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 3.0.

Key Takeaway

- Diversification strategies involve firmly stepping beyond its existing industries and entering a new value chain. Generally, related diversification (entering a new industry that has important similarities with a firm’s existing industries) is wiser than unrelated diversification (entering a new industry that lacks such similarities).

Exercises

- Studies have shown that executives’ pay increases when their firms gets larger. What role, if any, do you think executive pay plays in diversification decisions?

- Identify a firm that has recently engaged in diversification. Search the firm’s website to identify executives’ rationale for diversifying. Do you find the reasoning to be convincing? Why or why not?

References

Porter, M. E. 1987. From competitive advantage to corporate strategy. Harvard Business Review, 65(3), 102–121.

Prahalad, C. K., & Hamel, G. 1990. The core competencies of the corporation. Harvard Business Review, 86(1), 79–91.

Townhall, http://th2010.townhall.com/news/us/2011/03/20/zippos_burning_ambition_lies_in_ retail_expansion.