15.1 Invasive plants

Learning objectives

By the end of this lesson you will:

- Be able to explain the consequences of introducing non-native plants that become invasive.

- Be able to map how some plants become invasive.

- Know several examples of non-native invasive plants in Minnesota.

Overview

This lesson introduces some of the features and impacts of non-native invasive plants, using a Minnesota perspective. Be aware, however, that just as a plant native to an exotic continent may become a weedy invasive plant in Minnesota, some plants native to Minnesota have been taken to other continents and become invasive in their new homes. Invasive plants are defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as those non-native to an ecosystem whose introduction causes or is likely to cause economic or environmental harm or harm to human health. One example is the oriental bittersweet (Celasturs orbiculatus); the photo below shows, from near Red Wing, Minnesota, shows it smothering ground and tree vegetation.

Invasive plant species have contributed to the decline of about half of the endangered and threatened plant species in the U.S. Their impacts include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Competition with native plant species for moisture, sunlight, nutrients, and space.

- Decrease in biodiversity.

- Degradation of wildlife habitat, agriculture lands, and water quality.

- Increase in soil erosion.

- Decrease in recreational opportunities.

- If sexually compatible native plants are present in the invaded regions, hybrids can form resulting in genetic contamination or pollution to native environments.

This lesson reviews some of the common features of invasive plants in Minnesota, and includes specific information about several species.

Where do invasive plants come from?

People and plants have a close relationship, evolving a co-dependence over thousands of years. As people move around the globe they bring with them the plants that are useful for fuel, food, feed for their animals, enhancing the aesthetics of their new home, and providing fiber for clothing and construction. While most of these plants have been positive forces in the lives of people and do relatively no harm, some escape from cultivation and become invasive. In Minnesota, for example, the most reported invasive plant is common tansy (Tanacetum vulgare). It was likely first brought to the U.S. by John Winthrop, Governor of the Massachusetts Bay colony, about 400 years ago. Although humans are a primary dispersal means for invasive plants and often move them intentionally, such plants may also arrive unintentionally as contaminants in food plants or as seed contaminants in fodder that travels with people and their animals.

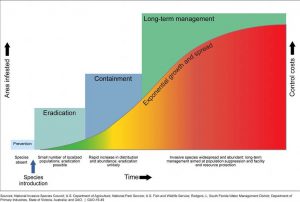

The graph above shows the relationship between an invasive plant’s spread and time. Initially, the spread is slow and is in a “lag phase” due to the small number of plants in the initial introduction. This lag phase (left third of the graph) is a period in which, if the plant is detected and addressed, control could result in its eradication. Most invasive plants, however, have a high rate of reproduction, either asexual or sexual. In many cases they spread by prolific fleshy fruit production (as with the bittersweet shown above) that is eaten by birds and other animals. As numbers of the invasive plant increase, it enters the exponential rate of spread (middle third of the graph). Think of exponential spread as a rate similar to 2, 4, 16, 256, 65536. If left unchecked, as some invasive plants are, spread will reach a maximum (shown in the last third of the graph). The horticultural industry is a common entry point for many invasive plants. The properties that make a plant attractive to growers and consumers for their yard or garden — including novelty, robust growth, abundant flowering over a long period of time, and easy sexual or asexual propagation — are the very qualities that make many ornamental introductions invasive.

In addition to large quantities of seed, invasive characteristics listed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Invasive Plant website include:

- Thriving on disturbed soil.

- Distribution by birds, wind, or humans over great distances.

- Aggressive root systems that spread long distances from a single plant.

- Root systems that grow so densely that they smother the root systems of surrounding vegetation.

- Production of chemicals in leaves or root systems that inhibit the growth of other plants around them (referred to as allelopathy).

As invasive plants spread they displace native vegetation, and can dramatically impact the ecosystem into which they are introduced.

Review questions

- What is an invasive plant?

- What is happening during the three phases of invasive plant spread?

- What impacts do invasive plants have on the environment?

- What are common properties of an invasive plant?

- If genetic pollution occurred, could it be reversed?

Invasive plant examples

Common tansy (Tanacetum vulgare)

Tansy, an herbaceous perennial in the family Asteraceae, is the most reported invasive plant in Minnesota. It was introduced to North America from Eurasia about 400 years ago, and has been used as a medicinal plant and a funerary herb because of its aroma. Rumor has it that the first president of Harvard University was buried with tansy, and when his grave was moved almost 200 years later, the tansy was still fragrant. Tansy’s invasion of pasture lands is problematic due to its toxicity to mammals. For more information on common tansy see the Minnesota Department of Agriculture website.

Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus)

Oriental bittersweet was intentionally introduced as an ornamental for dried floral arrangements and fall decorations (left-hand photo, below). It is a woody vine that climbs trees and structures and is capable of girdling the trees as the vines tighten around the truck (right-hand photo). Girdling plus the accumulated growth of heavy vines can bring down large trees. Oriental bittersweet thrives in a wide range of habitats, light levels, and soil types, and can grow to over 20 meters (65 ft) in length. Although it is on the Minnesota Department of Agriculture’s list of plants that are prohibited and must be eradicated, it is still grown and propagated in Wisconsin for use in floral arrangements.

|

|

Knotweeds (Fallopia sp.)

The knotweed complex consists of two species and their hybrid, includes Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica), giant knotweed (F. sachalinense), and their hybrid Bohemian knotweed (F. × bohemica). (Remember that an “×” between the genus and specific epithet indicates an interspecific hybrid.) The knotweed was originally imported as a novel ornamental. With its fast growth and late fall flowering it can make a very showy specimen planting. Each taxa of knotweed has very rapid growth. As an herbaceous perennial it resumes growth from large rhizomes (an underground stem) that produce prolific shoots and adventitious roots, making it difficult to control with herbicides.

Knotweeds can also cause damage to structures. With their long-lived rhizomes capable of adventitious rooting, and dioecious flowers capable of prolific seed set, knotweeds are a double threat to native plants and the environment.

Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii)

As a popular landscape plant, Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii) has been extensively bred, and many crosses have been made with related and sexually compatible barberries. It is planted in most areas of the University of Minnesota Twin Cities campuses. Barberry produces a fleshy drupe that is consumed and dispersed by birds. It has many sharp spines along the shoots and forms dense thickets. These thickets can prevent students from cutting across landscapes and provide excellent protection to small rodents (mice). As barberry populations increase, so do those of mice and other small rodents. Increased mouse populations are associated with increased tick populations (ticks are small, blood-sucking parasitic bugs) that may increase tick-borne diseases.

Winged burning bush or winged euonymus (Euonymus alatus)

Winged burning bush or winged euonymus (Euonymus alatus) is small tree or shrub from eastern Russia, central China, Korea, and Japan. It is very popular for the interesting wings on its stems and its brilliant red fall foliage. Its popularity for shade or sun landscape planting and ability to escape from cultivation means that escaped populations often occur in nature. This video shows a paddling trip to the Tellico River in Tennessee and the discovery of a large winged euonymus escaped from cultivation. Winged euonymus is adaptable to many growing conditions and forms dense canopies, reduces native native plant diversity. It is a popular landscape plant and still being propagated and sold in Minnesota. Fortunately, several researchers are breeding Euonymus cultivars with reduced or no seed set. How might these cultivars be propagated if they were sterile?

|

|

|

Common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica)

Common buckthorn is native to Europe and Asia and is a highly invasive perennial understory shrub or tree. Although propagation and sale of common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) are prohibited in Minnesota, it is common in both urban and natural habitats. There is, for example, a large and very old male buckthorn tree (a dioecious plant) at the corner of Cleveland Avenue North and Buford Avenue on “The Lawn” of the St. Paul Campus of the University of Minnesota.

|

|

|

Buckthorn was introduced to North America as an ornamental shrub and used for living fence rows and wildlife habitat. It has since spread aggressively across most of the northeast and upper Midwest through production and distribution of prolific fleshy fruit (middle photo, above). Common buckthorn has become a serious threat to native forest understory habitats, where it outcompetes native plant species. With such a large distribution, novel control methods are being tested such as goat grazing (above), which is showing success and has a reduced environmental impact compared to herbicide control.

These examples are a small sample of the plants that are known to be invasive in Minnesota. Fortunately for the horticulture industry, consumers, many scientists, and communities are engaged in eliminating invasive plants that have escaped into their environments.

Plant that is non-native to an ecosystem, and whose introduction causes or is likely to cause economic or environmental harm or harm to human health.

Where genes from GMO crops may escape to conventional crops or weedy relatives.

Phase during invasive plant spread that is slow due to a low number of plants being introduced.

Very rapid spread of an invasive plant as numbers and reproductive rates accelerate.

Horizontal stem growing just below the soil surface.