14.4 Plant Breeding

Learning objectives

By the end of this lesson you will:

- Understand how to get started breeding two common ornamental and food species.

- Know the purpose of emasculation when making hybridizations (crosses) between parents.

- Recognize the difference that propagation method makes in a plant breeding program.

Overview

This lesson presents examples of plant breeding of two common garden plants, rose and tomato. The strategies for the two plants differ because of how the final plant will be propagated. Roses are propagated asexually, while tomatoes are propagated by seed. For both, breeding starts with a cross between two different plants (called a bi-parental cross).

General information about rose

Watch this video for an introduction to breeding roses and identifying rose hips (1:49)

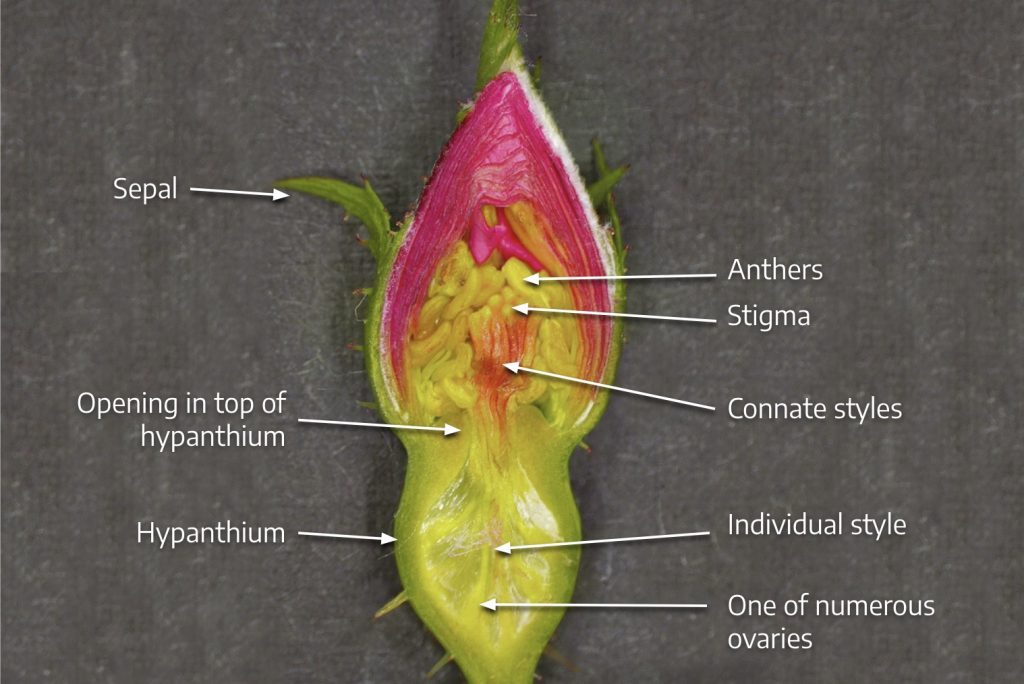

Rose (genus Rosa with many species) is a perennial, mostly deciduous (they annually lose their leaves), mostly temperate-climate shrub in the Rosaceae family. The rose flower is perfect. The calyx, corolla, and androecium whorls are fused at their bases to form a small cup-shaped structure called a hypanthium that surrounds the ovary. (Refer to Chapter 8 if these are not familiar terms.) The base of the hypanthium is attached to the receptacle. The hypanthium is the structure that ripens into a bright red or red-orange fruit called a “hip,” recall that this is also the tissue that forms the fleshy part of the apple. Within the hypanthium are hard achenes containing the rose seeds. In summary, the rose hip is an accessory fruit (parts other than ovary wall constitute the fleshy ripe portion) and an aggregate fruit (one flower, many carpels forming separate fruits) where the subsidiary fruits are achenes (optional).

The species of rose differ in their chromosome number, or ploidy. Roses have seven different types of chromosomes, so the total number of chromosomes in a rose is normally a multiple of seven. Some species, particularly wild species, are diploids with two sets of chromosomes, and so have a total of 14 (2 x 7 = 14) chromosomes. The large-flowered hybrid tea roses have four sets of chromosomes, so they are tetraploids with 28 (4 x 7 = 28) chromosomes. There are even triploid roses with 21 chromosomes. This optional journal article by Cédric Grossi & Maurice Jay on Chromosomes studies of rose cultivars provides more information on chromosome numbers. Some roses are sterile because of triploidy or an imbalance in chromosome numbers, and never form rose hips. Sterile roses cannot be used to breed new roses. From a practical standpoint, if the rose is fertile you can use it in backyard breeding without much concern about whether it is diploid or tetraploid.

Roses can self-pollinate or cross-pollinate. A breeding project should be started with a cross. Because the flowers are perfect, you need to emasculate (remove the anthers from) the flowers you intend to use as the female. Emasculation happens at the bud stage before the pollen has been released and before the stigma is receptive. If you wait too long, the pollen will be shed and the stigma may have received pollen from its own anthers. The commercial roses that you grow in your garden are normally the result of cross-pollination and are genetically highly heterozygous (the opposite of inbred), which in this case refers to most of the loci of plant being in a heterozygous condition or having two different alleles. High heterozygosity results in a more vigorous plant because the genome has increased diversity. Roses are asexually propagated by rooting or grafting cuttings of desirable plants so that superior genotypes are maintained and not broken up by meiotic cell division, as would happen through seed propagation.

General information about tomato

Tomato, Solanum lycopersicon, is a member of the Solenaceae family, the same family that contains potato, pepper, tobacco, and nightshade. The crop has a fascinating history, starting with its likely origin in Peru, importation to Europe with returning explorers, gradual introduction into European cuisine (some cultures associated tomato with nightshade and considered it poisonous), and introduction to North America. This optional tomato history page describes one version of this history.

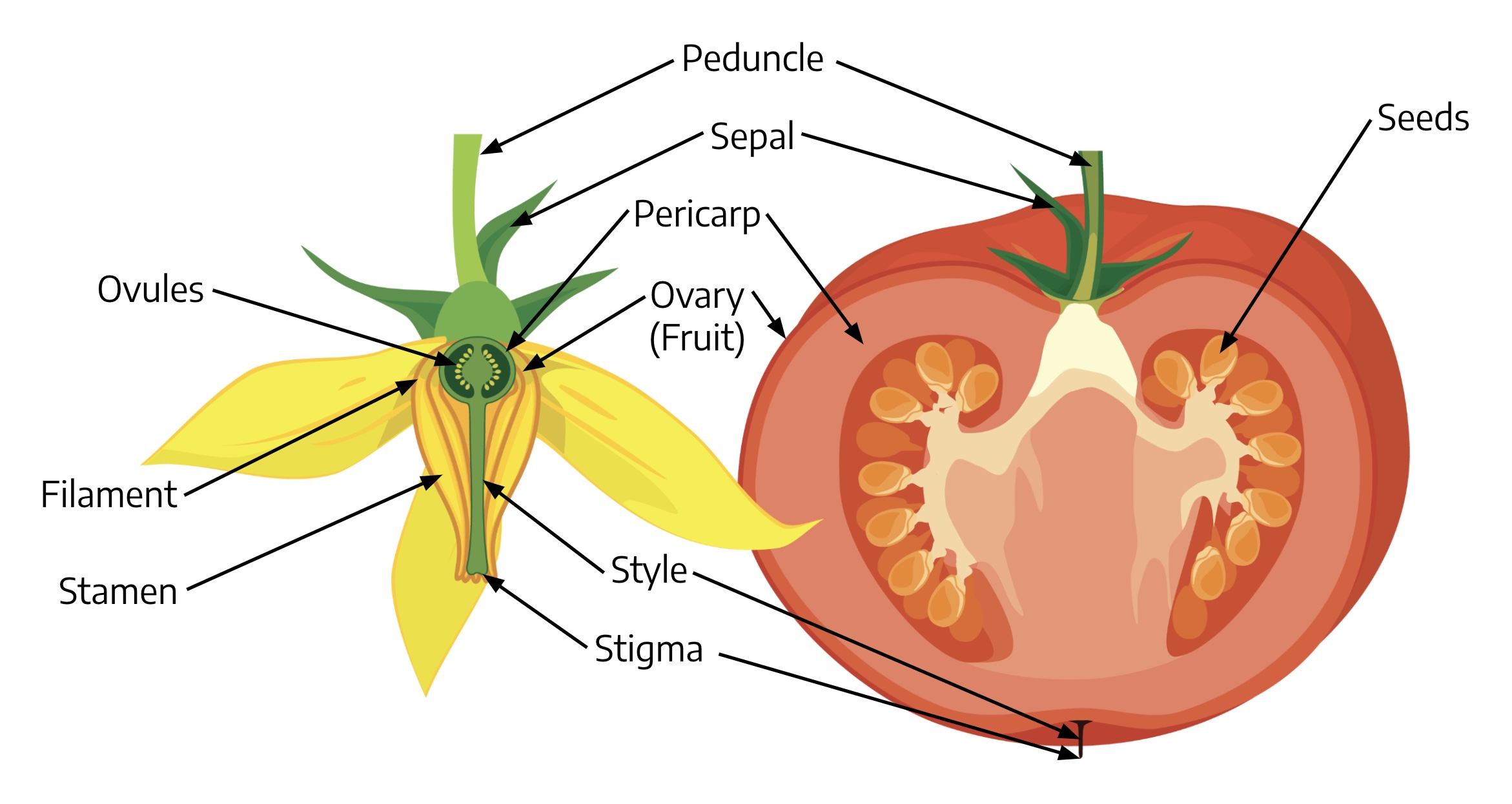

The tomato flower is perfect (in the botanical sense). The anthers form a cone that completely surrounds the gynoecium. In wild tomatoes, the stigma and style protrude up above the cone of anthers, so these wild types tend to cross-pollinate. The stigma of domesticated tomatoes is either just slightly above the cone, or buried within the cone. Domesticated tomatoes self-pollinate, so we will also need to emasculate the female plants in our crosses. The pistil is made up of several fused carpels, and the mature fruit is a berry.

In contrast to rose, all tomatoes, whether wild or domesticated, are diploids where 2n = 24. They will all cross with each other. Domesticated tomatoes that you grow in your garden are either highly homozygous (inbred) or are F1 hybrids and highly heterozygous. Heirloom and older style tomatoes are typically inbreds (sometimes called pure lines or [incorrectly] open pollinated in seed catalogs), while modern and commercial tomatoes are F1 hybrids. You can use either heirloom or commercial hybrid types in your breeding experiments. Tomatoes are propagated by seeds.

Review questions

- Compare and contrast rose and tomato for their ploidy and method of propagation.

- How does the variation in ploidy affect rose breeding? Does it have the same impact on tomato breeding?

- What is emasculation and why is it done? Which parent do you emasculate, or do you emasculate both parents?

Rose breeding

The overall strategy:

- Identify your objective.

- Choose your parents.

- Make controlled crosses among parents.

- Plant the F1 seeds.

- Evaluate the offspring over a few years.

- Keep seeds from the best plants and compost the rest.

- Asexually propagate the very best one or two by stem cuttings.

- Sell the rights to your award-winning rose to a nursery who distributes it worldwide.

You should start a breeding project with an objective in mind. At first, your objective will probably be just to see if the process works. Later, you will have specific characteristics in mind that you would like to emphasize in the progeny from the cross. Step two is to choose your parents; at least one of the parents should have the trait you are interested in — like flower color, disease resistance, or cold hardiness for surviving Minnesota winters. The other parent should have complementary traits, like size, branching, floral scent, or long vase life.

In a rose, you might choose as the female a nice shrub rose with an attractive red flower and that has made it through several winters without special care. If it has nice full rose hips at the end of the year, you know it’s fertile. Perhaps you’d like the new rose to have the same flower type and color, but in a dwarf plant. And perhaps your neighbor has a dwarf rose that sets hips and must be fertile, and you can use some pollen from that rose even though you don’t like the color of its flower. Hopefully, you’ll get some offspring that show the same red as your female, but in the dwarf growth habit. (You’ll probably get some sprawling, gangly rose plants with ugly flowers as well, but you can toss them in the compost.)

Try the cross in the opposite direction as well (switch which plant is male and which is female). This is called a reciprocal cross. Sometimes the cross is easier to make in one “direction” (A x B vs B x A) than the other. When writing a pedigree for the cross, which shows the names of the two parents, remember to write the female first — cross A x B, for instance, means plant A was the female. Breeders sometimes write the pedigree with a slash (“/”) rather than an “X:” A/B.

By making several crosses that meet your objectives, you increase your chance of obtaining the specific combination of alleles for the specific traits. If a plant meets your objectives it can be asexually propagated, not by seed, so that you keep the genotype intact in your propagules.

Rose hybridization

The main steps in crossing are:

- Choose buds at the right stage.

- Emasculate the female.

- Collect pollen from the male.

- Transfer pollen from anther of male to stigma of female.

- Identify the cross with a tag.

- Protect the carpel until the ovary begins to swell.

Rose hybridization is a sufficiently popular hobby among gardeners that there are websites with reasonably easy-to-follow instructions. This is a good example from a rose breeding project (12:18 min).

The Santa Clarita Rose Society in California has an informative hybridization page, with photos and descriptions of the rose flower before and after emasculation, pollen transfer with an artist’s brush, and the resulting hips and achenes.

While you may get your first bloom when your new hybrid is just a seedling, you won’t know whether you have a really good rose until you have grown it outdoors for two or three years. Once you think you have something you want to propagate, use stem cuttings to propagate the selected plant.

Roses are a good example of a common garden plant you can hybridize. You germinate the resulting seeds, evaluate the progeny, and then asexually propagate the plants you like. It will take at least three years or more to identify plants that maintain the traits you desire to continue through multiple years and environments.

Review questions

- When making a cross, why is staging the flower development important for emasculation and pollination?

- In the cross MN5125 / ND163 which of the two parents do you emasculate?

- What is a reciprocal cross?

Tomato breeding

The overall strategy:

- Identify your objective.

- Choose your parents.

- Make controlled crosses among parents.

- Plant the F1 seeds.

- Evaluate the offspring for the characteristics you are most interested in.

- Keep the seed from the best plants and begin inbreeding.

- Grow the seed from the best plants next spring or in a greenhouse.

- Select the best plants, allow their flowers to self, and keep the seed.

- Repeat the last two steps for about 5–7 generations. Notice that the progeny are now very similar to each other.

- Somewhere around year 5 or 6, identify the best plant that will be the founder of your new, pure line (true breeding) tomato cultivar.

- Sell the rights to your award-winning tomato to a seed company who distributes it worldwide.

Notice that the rose and tomato strategy lists are not identical. With roses, we planted out the seeds from the hybridization, took a few years identifying the best plants, and propagated them asexually. With tomatoes, we want to develop pure lines by inbreeding. Inbreeding is producing seed by selfing over 5–7 generations to develop plants that are highly homozygous at most loci in their genomes. Homozygosity results in identical plants propagated by seed. This is done so the resulting progeny look more and more alike until, after 4–6 years, plants grown from seeds harvested off the same plant are indistinguishable from each other. At that point you have an inbred pure line that will be true breeding if self-pollinated, and you can be pretty sure that you know what you’re going to get when you plant seed from year to year. The seed from inbred pure lines are the same because all loci are homozygous, so all gametes are the same and fertilization produces clonal seeds.

Again, identify your objectives and then choose the parents. You might like the cherry tomato that you’ve been growing on the patio because the fruits are perfect for salads. But being a loyal Gopher, you’d like a gold fruit rather than one that’s Badger red. So you reciprocally cross the red patio tomato with the gold beefsteak type tomato and begin assessing progeny.

Tomato hybridization

- Choose buds at the right stage.

- Emasculate the female.

- Collect pollen from the male.

- Transfer pollen from anther of male to stigma of female.

- Identify the cross with a tag.

- Collect seed at maturity.

This is a practical video on crossing tomatoes (2:18 min).

Dehybridizing

Most new commercial tomatoes, including new garden tomatoes, are F1 hybrids. The seeds you plant in the field are the result of crossing two parents, as described above. By planting the F1 hybrid, the grower capitalizes on the extra vigor associated with a highly heterozygous hybrid genotype. This website (optional) discusses hybrid tomatoes vs. saving the seed from the hybrid to plant. It’s an interesting discussion, but remember that science is a systematic study and requires replications, something you don’t get from planting seeds from a hybrid in a single year. If you collect seed from a hybrid tomato fruit, whether from a hybrid plant in your garden or a fruit from the grocery store, those seeds are F2 seeds. By planting those seeds out, selecting the most vigorous seedlings, and later in the year keeping seeds from the plants with the best fruits, you are following the same steps laid out in the tomato breeding section, except that you fast-forwarded past the crossing and F1 grow-out stage and went directly to the F2. If you continue to grow out the seed and select the best plants for a few more years, you will end up with a stable variety of your own. This process is called dehybridizing because you are starting with a hybrid, but after several generations of production, selection, and seed saving you are creating new pure lines from that hybrid.

This approach will work well with hybrid tomatoes and hybrid peppers because they are naturally self-pollinating. Garden catalogs will tell you whether the seed you are buying is hybrid. If you are getting your fruits from the store, you can count on them being hybrids unless they are marked as heirloom. The upside of dehybridizing is that it’s the easiest way to breed your own crop because you don’t have to emasculate and cross. The downside is that you are breeding “blind.” You didn’t choose the parents for the F1 cross to achieve your objective, and you don’t know the parents’ characteristics, so the phenotypes that you get from dehybridizing are anyone’s guess.

Review questions

- Why do you have to allow tomato to self-pollinate for several generations after you make the hybridization?

- Why dehybridize? What type of crop (naturally inbreeding or naturally outcrossing) would you be most likely to dehybridize? What is the downside of dehybridizing?