2.4 Perception

Learning Objectives

- Understand the influence of biases in the process of perception.

- Describe how we perceive visual objects and how these tendencies may affect our behavior.

- Describe the biases of self-perception.

- Describe the biases inherent in our perceptions of other people.

Our behavior is not only a function of our personality and values but also of the situation. We interpret our environment, formulate responses, and act accordingly. Perception may be defined as the process by which individuals detect and interpret environmental stimuli. What makes human perception so interesting is that we do not solely respond to the stimuli in our environment. We go beyond the information that is present in our environment, pay selective attention to some aspects of the environment, and ignore other elements that may be immediately apparent to other people.

Our perception of the environment is not entirely rational. For example, have you ever noticed that while glancing at a newspaper or a news Web site, information that is especially interesting or important to you jumps out of the page and catches your eye? If you are a sports fan, while scrolling down the pages, you may immediately see a news item describing the latest success of your team. If you are the mother of a picky eater, an advice column on toddler feeding may be the first thing you see when looking at the page. If you were recently turned down for a loan, an item of financial news may jump out at you. Therefore, what we see in the environment is a function of what we value, our needs, our fears, and our emotions(Higgins & Bargh, 1987; Keltner, et. al., 1993). In fact, what we see in the environment may be objectively flat out wrong because of such mental tendencies. For example, one experiment showed that when people who were afraid of spiders were shown spiders, they inaccurately thought that the spider was moving toward them (Riskind, et. al., 1995).

In this section, we will describe some common perceptual tendencies we engage in when perceiving objects or other people and the consequences of such perceptions. Our coverage of these perceptual biases is not exhaustive—there are many other biases and tendencies that can be found in the way people perceive stimuli.

Visual Perception

Our visual perception definitely goes beyond the physical information available to us; this phenomenon is commonly referred to as “optical illusions.” Artists and designers of everything from apparel to cars to home interiors make use of optical illusions to enhance the look of the product. Managers rely on their visual perception to form their opinions about people and objects around them and to make sense of data presented in graphical form. Therefore, understanding how our visual perception may be biased is important.

First, we extrapolate from the information available to us. Take a look at the first figure. The white triangle you see in the middle is not really there, but we extrapolate from the information available to us and see it there. Similarly, when we look at objects that are partially blocked, we see the whole (Kellman & Shipley, 1991).

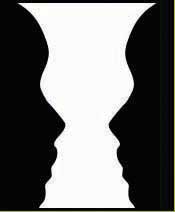

Now, look at the next figure. What do you see? Most people look at this figure and see two faces or a goblet, depending on which color—black or white—they focus upon. Our visual perception is often biased because we do not perceive objects in isolation. The contrast between our focus of attention and the remainder of the environment may make an object appear bigger or smaller.

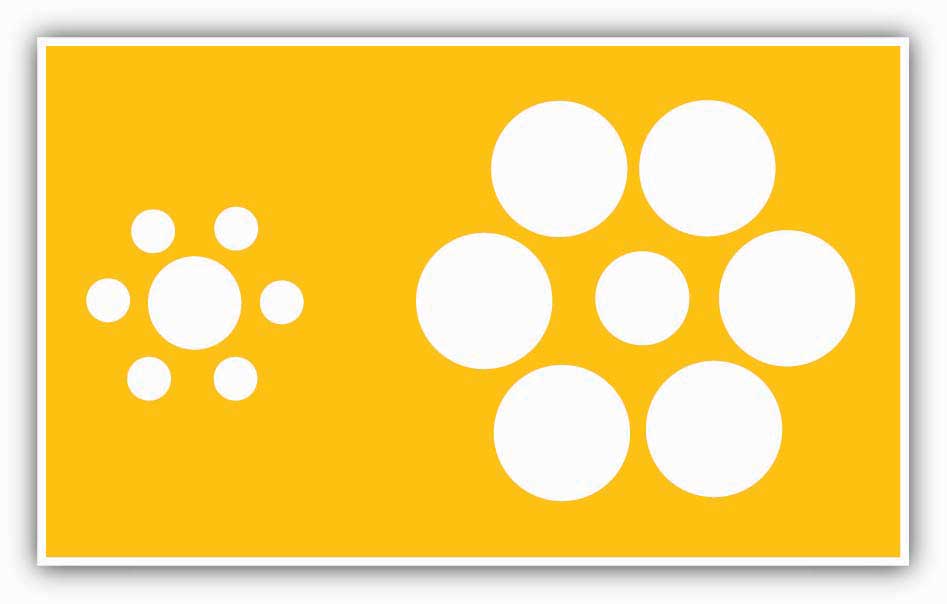

This principle is shown here in the third figure. At first glance, the circle on the left may appear bigger, but they are the same size. This is due to the visual comparison of the middle circle on the left with its surrounding circles, whereas the middle circle on the right is compared with the bigger circles surrounding it.

How do these tendencies influence behavior in organizations? The fact that our visual perception is faulty means that managers should not always take what they see at face value. Let’s say that you do not like one of your peers and you think that you saw this person surfing the Web during work hours. Are you absolutely sure, or are you simply filling the gaps? Have you really seen this person surf unrelated Web sites, or is it possible that the person was searching for work-related purposes? The tendency to fill in the gaps also causes our memory to be faulty. Imagine that you have been at a meeting where several people made comments that you did not agree with. After the meeting, you may attribute most of these comments to people you did not like. In other words, you may twist the reality to make your memories more consistent with your opinions of people.

The tendency to compare and contrast objects and people to each other also causes problems. For example, if you are a manager who has been given an office much smaller than the other offices on the floor, you may feel that your workspace is crowded and uncomfortable. If the same office is surrounded by smaller offices, you may actually feel that your office is comfortable and roomy. In short, our biased visual perception may lead to the wrong inferences about the people and objects around us.

Self-Perception

Human beings are prone to errors and biases when perceiving themselves. Moreover, the type of bias people have depends on their personality. Many people suffer from self-enhancement bias. This is the tendency to overestimate our performance and capabilities and see ourselves in a more positive light than others see us. People who have a narcissistic personality are particularly subject to this bias, but many others also have this bias to varying degrees (John & Robins, 1994). At the same time, other people have the opposing extreme, which may be labeled as self-effacement bias (or modesty bias). This is the tendency to underestimate our performance and capabilities and to see events in a way that puts ourselves in a more negative light. We may expect that people with low self-esteem may be particularly prone to making this error. These tendencies have real consequences for behavior in organizations. For example, people who suffer from extreme levels of self-enhancement tendencies may not understand why they are not getting promoted or rewarded, while those who have a tendency to self-efface may project low confidence and take more blame for their failures than necessary.

When human beings perceive themselves, they are also subject to the false consensus error. Simply put, we overestimate how similar we are to other people (Fields & Schuman, 1976; Ross, et. al., 1977). We assume that whatever quirks we have are shared by a larger number of people than in reality. People who take office supplies home, tell white lies to their boss or colleagues, or take credit for other people’s work to get ahead may genuinely feel that these behaviors are more common than they really are. The problem for behavior in organizations is that, when people believe that a behavior is common and normal, they may repeat the behavior more freely. Under some circumstances, this may lead to a high level of unethical or even illegal behaviors.

Social Perception

How we perceive other people in our environment is also shaped by our biases. Moreover, how we perceive others will shape our behavior, which in turn will shape the behavior of the person we are interacting with.

One of the factors biasing our perception is stereotypes. Stereotypes are generalizations based on a group characteristic. For example, believing that women are more cooperative than men or that men are more assertive than women are stereotypes. Stereotypes may be positive, negative, or neutral. In the abstract, stereotyping is an adaptive function—we have a natural tendency to categorize the information around us to make sense of our environment. Just imagine how complicated life would be if we continually had to start from scratch to understand each new situation and each new person we encountered! What makes stereotypes potentially discriminatory and a perceptual bias is the tendency to generalize from a group to a particular individual. If the belief that men are more assertive than women leads to choosing a man over an equally qualified female candidate for a position, the decision will be biased, unfair, and potentially illegal.

Stereotypes often create a situation called self-fulfilling prophecy. This happens when an established stereotype causes one to behave in a certain way, which leads the other party to behave in a way that confirms the stereotype (Snyder, et. al., 1977). If you have a stereotype such as “Asians are friendly,” you are more likely to be friendly toward an Asian person. Because you are treating the other person more nicely, the response you get may also be nicer, which confirms your original belief that Asians are friendly. Of course, just the opposite is also true. Suppose you believe that “young employees are slackers.” You are less likely to give a young employee high levels of responsibility or interesting and challenging assignments. The result may be that the young employee reporting to you may become increasingly bored at work and start goofing off, confirming your suspicions that young people are slackers!

Stereotypes persist because of a process called selective perception. Selective perception simply means that we pay selective attention to parts of the environment while ignoring other parts, which is particularly important during the Planning process. Our background, expectations, and beliefs will shape which events we notice and which events we ignore. For example, an executive’s functional background will affect the changes he or she perceives in the environment (Waller, et. al., 1995). Executives with a background in sales and marketing see the changes in the demand for their product, while executives with a background in information technology may more readily perceive the changes in the technology the company is using. Selective perception may also perpetuate stereotypes because we are less likely to notice events that go against our beliefs. A person who believes that men drive better than women may be more likely to notice women driving poorly than men driving poorly. As a result, a stereotype is maintained because information to the contrary may not even reach our brain!

Let’s say we noticed information that goes against our beliefs. What then? Unfortunately, this is no guarantee that we will modify our beliefs and prejudices. First, when we see examples that go against our stereotypes, we tend to come up with subcategories. For example, people who believe that women are more cooperative when they see a female who is assertive may classify her as a “career woman.” Therefore, the example to the contrary does not violate the stereotype and is explained as an exception to the rule (Higgins & Bargh, 1987). Or, we may simply discount the information. In one study, people in favor of and against the death penalty were shown two studies, one showing benefits for the death penalty while the other disconfirming any benefits. People rejected the study that went against their belief as methodologically inferior and ended up believing in their original position even more (Lord, et. al., 1979)! In other words, using data to debunk people’s beliefs or previously established opinions may not necessarily work, a tendency to guard against when conducting Planning and Controlling activities.

Figure 2.13

First impressions are lasting. A job interview is one situation where first impressions formed during the first few minutes may have consequences for your relationship with your future boss or colleagues.

adabara – CC0 public domain.

One other perceptual tendency that may affect work behavior is first impressions. The first impressions we form about people tend to have a lasting effect. In fact, first impressions, once formed, are surprisingly resilient to contrary information. Even if people are told that the first impressions were caused by inaccurate information, people hold on to them to a certain degree because once we form first impressions, they become independent from the evidence that created them (Ross, et. al., 1975). Therefore, any information we receive to the contrary does not serve the purpose of altering them. Imagine the first day that you met your colleague Anne. She treated you in a rude manner, and when you asked for her help, she brushed you off. You may form the belief that Anne is a rude and unhelpful person. Later on, you may hear that Anne’s mother is seriously ill, making Anne very stressed. In reality, she may have been unusually stressed on the day you first met her. If you had met her at a time when her stress level was lower, you could have thought that she is a really nice person. But chances are, your impression that she is rude and unhelpful will not change even when you hear about her mother. Instead, this new piece of information will be added to the first one: She is rude, unhelpful, and her mother is sick.

As a manager, you can protect yourself against this tendency by being aware of it and making a conscious effort to open your mind to new information. It would also be to your advantage to pay careful attention to the first impressions you create, particularly during job interviews.

Key Takeaway

Perception is how we make sense of our environment in response to environmental stimuli. While perceiving our surroundings, we go beyond the objective information available to us and our perception is affected by our values, needs, and emotions. There are many biases that affect human perception of objects, self, and others. When perceiving the physical environment, we fill in the gaps and extrapolate from the available information. When perceiving others, stereotypes influence our behavior. Stereotypes may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies. Stereotypes are perpetuated because of our tendency to pay selective attention to aspects of the environment and ignore information inconsistent with our beliefs. Understanding the perception process gives us clues to understanding human behavior.

Exercises

- What are some of the typical errors, or optical illusions, that we experience when we observe physical objects?

- What are the problems of false consensus error? How can managers deal with this tendency?

- Describe a situation where perception biases have or could affect any of the P-O-L-C facets. Use an example you have experienced or observed, or, if you do not have such an example, create a hypothetical situation. How do we manage the fact that human beings develop stereotypes? Is there such as thing as a good stereotype? How would you prevent stereotypes from creating unfairness in management decisions?

- Describe a self-fulfilling prophecy you have experienced or observed in action. Was the prophecy favorable or unfavorable? If unfavorable, how could the parties have chosen different behavior to produce a more positive outcome?

References

Fields, J. M., & Schuman, H. (1976). Public beliefs about the beliefs of the public. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 40 (4), 427–448.

Higgins, E. T., & Bargh, J. A. (1987). Social cognition and social perception. Annual Review of Psychology, 38, 369–425.

John, O. P., & Robins, R. W. (1994). Accuracy and bias in self-perception: Individual differences in self-enhancement and the role of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 206–219.

Kellman, P. J., & Shipley, T. F. (1991). A theory of visual interpolation in object perception. Cognitive Psychology, 23, 141–221.

Keltner, D., Ellsworth, P. C., & Edwards, K. (1993). Beyond simple pessimism: Effects of sadness and anger on social perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 740–752.

Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1979) Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 2098–2109.

Riskind, J. H., Moore, R., & Bowley, L. (1995). The looming of spiders: The fearful perceptual distortion of movement and menace. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 171.

Ross, L., Greene, D., & House, P. (1977). The “false consensus effect”: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13, 279–301.

Ross, L., Lepper, M. R., & Hubbard, M. (1975). Perseverance in self-perception and social perception: Biased attributional processes in the debriefing paradigm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32, 880–892.

Snyder, M., Tanke, E. D., & Berscheid, E. (1977). Social perception and interpersonal behavior: On the self-fulfilling nature of social stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 656–666.

Waller, M. J., Huber, G. P., & Glick, W. H. (1995). Functional background as a determinant of executives’ selective perception. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 943–974.