15.4 Types and Levels of Control

Learning Objectives

- Know the difference between strategic and operational controls.

- Understand the different types of controls.

- Be able to differentiate between financial and nonfinancial controls.

Figure 15.4

Controls allow you to align the pieces with the big picture.

Jason7825 – A 3D Jigsaw Puzzle – public domain.

Recognizing that organizational controls can be categorized in many ways, it is helpful at this point to distinguish between two sets of controls: (1) strategic controls and (2) management controls, sometimes called operating controls (Harrison & St. John, 2002).

Two Levels of Control: Strategic and Operational

Imagine that you are the captain of a ship. The strategic controls make sure that your ship is going in the right direction; management and operating controls make sure that the ship is in good condition before, during, and after the voyage. With that analogy in mind, strategic control is concerned with tracking the strategy as it is being implemented, detecting any problem areas or potential problem areas suggesting that the strategy is incorrect, and making any necessary adjustments (Venkataraman & Saravathy, 2001). Strategic controls allow you to step back and look at the big picture and make sure all the pieces of the picture are correctly aligned.

Ordinarily, a significant time span occurs between initial implementation of a strategy and achievement of its intended results. For instance, if you wanted to captain your ship from San Diego to Seattle you might need a crew, supplies, fuel, and so on. You might also need to wait until the weather lets you make the trip safely! Similarly, in larger organizations, during the time you are putting the strategy into place, numerous projects are undertaken, investments are made, and actions are undertaken to implement the new strategy. Meanwhile, the environmental situation and the firm’s internal situation are developing and evolving. The economy could be booming or perhaps falling into recession. Strategic controls are necessary to steer the firm through these events. They must provide some means of correcting direction on the basis of intermediate performance and new information.

Operational control, in contrast to strategic control, is concerned with executing the strategy. Where operational controls are imposed, they function within the framework established by the strategy. Normally these goals, objectives, and standards are established for major subsystems within the organization, such as business units, projects, products, functions, and responsibility centers (Mattews, 1999). Typical operational control measures include return on investment, net profit, cost, and product quality. These control measures are essentially summations of finer-grained control measures. Corrective action based on operating controls may have implications for strategic controls when they involve changes in the strategy.

Types of Control

It is also valuable to understand that, within the strategic and operational levels of control, there are several types of control. The first two types can be mapped across two dimensions: level of proactivity and outcome versus behavioral. The following table summarizes these along with examples of what such controls might look like.

Proactivity

Proactivity can be defined as the monitoring of problems in a way that provides their timely prevention, rather than after the fact reaction. In management, this is known as feedforward control; it addresses what can we do ahead of time to help our plan succeed. The essence of feedforward control is to see the problems coming in time to do something about them. For instance, feedforward controls include preventive maintenance on machinery and equipment and due diligence on investments.

Table 15.1 Types and Examples of Control

| Control Proactivity | Behavioral control | Outcome control |

|---|---|---|

| Feedforward control | Organizational culture | Market demand or economic forecasts |

| Concurrent control | Hands-on management supervision during a project | The real-time speed of a production line |

| Feedback control | Qualitative measures of customer satisfaction | Financial measures such as profitability, sales growth |

Concurrent Controls

The process of monitoring and adjusting ongoing activities and processes is known as concurrent control. Such controls are not necessarily proactive, but they can prevent problems from becoming worse. For this reason, we often describe concurrent control as real-time control because it deals with the present. An example of concurrent control might be adjusting the water temperature of the water while taking a shower.

Feedback Controls

Finally, feedback controls involve gathering information about a completed activity, evaluating that information, and taking steps to improve the similar activities in the future. This is the least proactive of controls and is generally a basis for reactions. Feedback controls permit managers to use information on past performance to bring future performance in line with planned objectives.

Control as a Feedback Loop

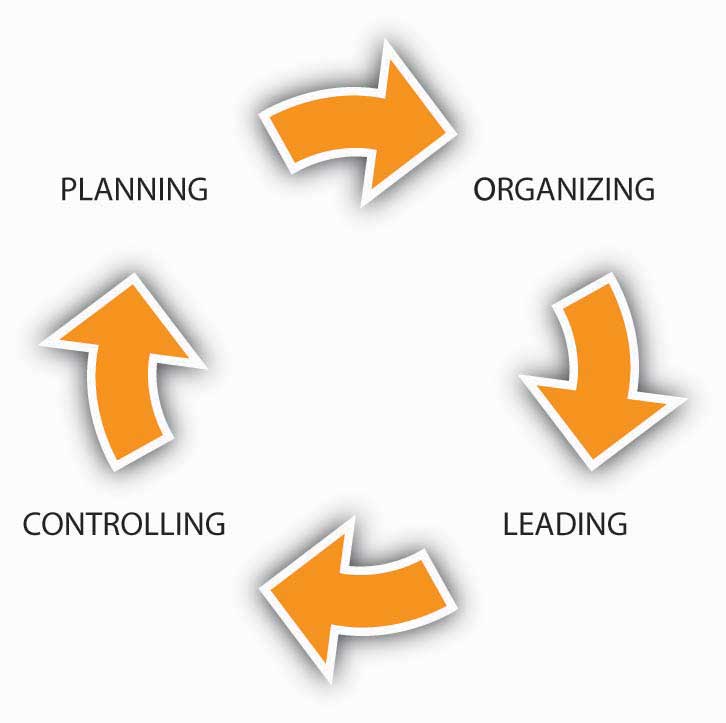

In this latter sense, all these types of control function as a feedback mechanism to help leaders and managers make adjustments in the strategy, as perhaps is reflected by changes in the planning, organizing, and leading components. This feedback loop is characterized in the following figure.

Why might it be helpful for you to think of controls as part of a feedback loop in the P-O-L-C process? Well, if you are the entrepreneur who is writing the business plan for a completely new business, then you would likely start with the planning component and work your way to controlling—that is, spell out how you are going to tell whether the new venture is on track. However, more often, you will be stepping into an organization that is already operating, and this means that a plan is already in place. With the plan in place, it may be then up to you to figure out the organizing, leading, or control challenges facing the organization.

Outcome and Behavioral Controls

Controls also differ depending on what is monitored, outcomes or behaviors. Outcome controls are generally preferable when just one or two performance measures (say, return on investment or return on assets) are good gauges of a business’s health. Outcome controls are effective when there’s little external interference between managerial decision making on the one hand and business performance on the other. It also helps if little or no coordination with other business units exists.

Behavioral controls involve the direct evaluation of managerial and employee decision making, not of the results of managerial decisions. Behavioral controls tie rewards to a broader range of criteria, such as those identified in the Balanced Scorecard. Behavioral controls and commensurate rewards are typically more appropriate when there are many external and internal factors that can affect the relationship between a manager’s decisions and organizational performance. They’re also appropriate when managers must coordinate resources and capabilities across different business units.

Financial and Nonfinancial Controls

Finally, across the different types of controls in terms of level of proactivity and outcome versus behavioral, it is important to recognize that controls can take on one of two predominant forms: financial and nonfinancial controls. Financial control involves the management of a firm’s costs and expenses to control them in relation to budgeted amounts. Thus, management determines which aspects of its financial condition, such as assets, sales, or profitability, are most important, tries to forecast them through budgets, and then compares actual performance to budgeted performance. At a strategic level, total sales and indicators of profitability would be relevant strategic controls.

Without effective financial controls, the firm’s performance can deteriorate. PSINet, for example, grew rapidly into a global network providing Internet services to 100,000 business accounts in 27 countries. However, expensive debt instruments such as junk bonds were used to fuel the firm’s rapid expansion. According to a member of the firm’s board of directors, PSINet spent most of its borrowed money “without the financial controls that should have been in place (Woolley, 2001).” With a capital structure unable to support its rapidly growing and financially uncontrolled operations, PSINet and 24 of its U.S. subsidiaries eventually filed for bankruptcy (PSINet, 2001). While we often think of financial controls as a form of outcome control, they can also be used as a behavioral control. For instance, if managers must request approval for expenditures over a budgeted amount, then the financial control also provides a behavioral control mechanism as well.

Increasing numbers of organizations have been measuring customer loyalty, referrals, employee satisfaction, and other such performance areas that are not financial. In contrast to financial controls, nonfinancial controls track aspects of the organization that aren’t immediately financial in nature but are expected to lead to positive performance outcomes. The theory behind such nonfinancial controls is that they should provide managers with a glimpse of the organization’s progress well before financial outcomes can be measured (Ittner & Larcker, 2003). And this theory does have some practical support. For instance, GE has found that highly satisfied customers are the best predictor of future sales in many of its businesses, so it regularly tracks customer satisfaction.

Key Takeaway

Organizational controls can take many forms. Strategic controls help managers know whether a chosen strategy is working, while operating controls contribute to successful execution of the current strategy. Within these types of strategy, controls can vary in terms of proactivity, where feedback controls were the least proactive. Outcome controls are judged by the result of the organization’s activities, while behavioral controls involve monitoring how the organization’s members behave on a daily basis. Financial controls are executed by monitoring costs and expenditure in relation to the organization’s budget, and nonfinancial controls complement financial controls by monitoring intangibles like customer satisfaction and employee morale.

Exercises

- What is the difference between strategic and operating controls? What level of management would be most concerned with operating controls?

- If feedforward controls are the most proactive, then why do organizations need or use feedback controls?

- What is the difference between behavioral and outcome controls?

- What is the difference between nonfinancial and financial controls? Is a financial control a behavioral or an outcome control?

References

Harrison, J. S., & St. John, C. H. (2002). Foundations in Strategic Management (2nd ed., 118–129). Cincinnati, OH: South-Western College.

Ittner, C., & Larcker, D. F. (2003, November). Coming up short on nonfinancial performance measurement. Harvard Business Review, 2–8.

Matthews, J. (1999). Strategic moves. Supply Management, 4(4), 36–37.

PSINet, retrieved January 30, 2009, from PSINet announces NASDAQ delisting. (2001, June 1). http://www.psinet.com.

Venkataraman, S., & Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). Strategy and entrepreneurship: Outlines of an untold story. In M. A. Hitt, R. E. Freeman, & J. S. Harrison (Eds.), Handbook of strategic management (650–668). Oxford: Blackwell.

Woolley, S. (2001, May). Digital hubris. Forbes, 66–70.