Chapter 4. Planting, Maintenance, and Management

4.3 Management

But I thought they were low maintenance?

In general, native grasses are low maintenance, but like any plant, they can have periodic issues that require management. This chapter covers the most common problems that can occur with native grasses.

Lodging

Sometimes completely healthy grasses will flop over, or lodge. Lodging can happen at the root or the stem level and is considered any displacement in the plant from a vertical position. It is a common problem in grasses and affects field grasses as well as ornamental grasses.

Many factors can play a role in lodging, making it hard to pinpoint the exact cause. Factors include weather, soil type, sunlight, genetics, and topography. Lodging is often associated with high nutrient loads in the soil, such as excess nitrogen. Lodging is also partially genetic. Some cultivars are more prone to lodging than others.

To help prevent lodging, make sure to plant grasses in appropriate sites. Manage your plants by dividing them and cutting back or burning them each year. This prevents grasses from getting too big and heavy at the top. Avoid planting in shade or low light conditions, which can increase lodging.

Cold Hardiness

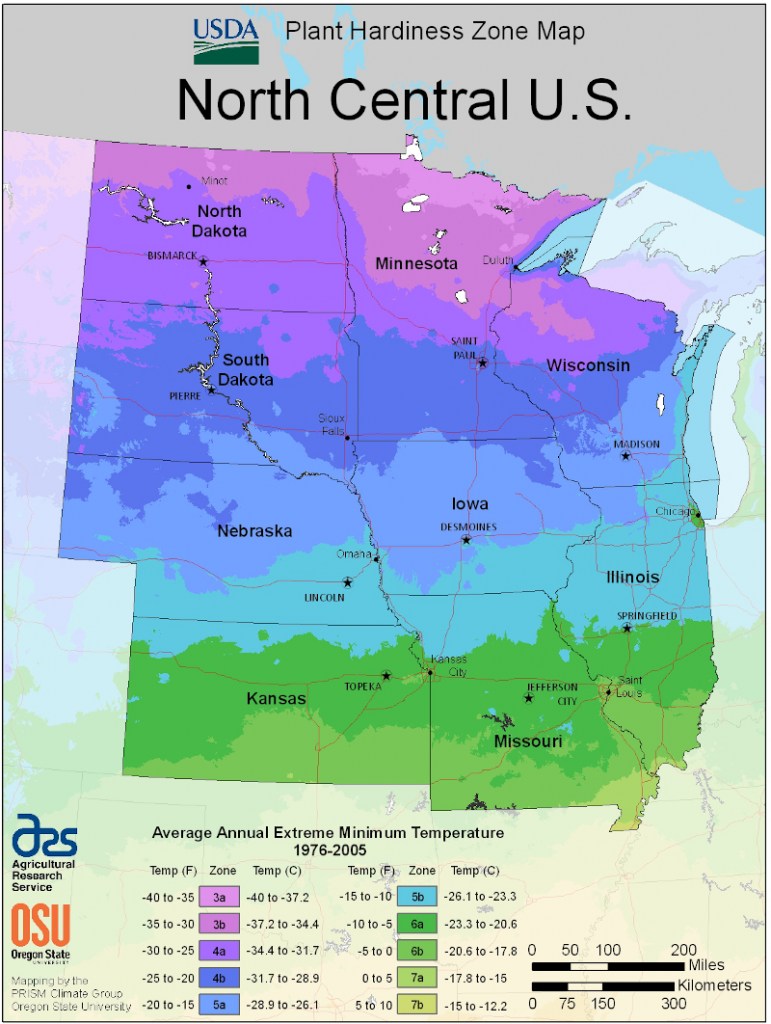

Hardiness refers to the temperature range in which a plant can grow successfully. The USDA plant hardiness zone map gives the average annual minimum winter temperatures in 10 degree zones across the United States. If a grass is native to your region then it should be winter hardy. However, the distribution of many native grasses, especially prairie grasses, spans large geographical regions. For example, blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis) grows from Saskatchewan to Mexico. Because it occurs across such varied climates, there is variation within the species. For example, the nativar ‘Blonde Ambition’, which was selected from New Mexico, has limited hardiness in zone 4 and may not be hardy at all in zone 3 or 2.

Keep this in mind when purchasing nativars from garden centers and make sure to double check the zones on the tag. If buying native seed, check the source of the seed, and make sure it comes from a local seed source (usually within 200–300 miles).

Pests and Pathogens

Pests and pathogens are rare in native grasses, but they are not entirely immune. Fungus in various forms, affects grasses. One such form, rust, can occur on many different grasses, but most commonly affects reed grass, reed canary grass, big bluestem, little bluestem, and switchgrass. Rust is not a fatal disease, but it does discolor foliage. Switchgrass and reed canary grass are prone to leaf spot and blight diseases, especially during wet growing seasons, and root and stem rot pathogens. Smut and head scab have also been known to affect switchgrass (Gleason et al. 2009). Fungal diseases are more damaging to some of the blue cultivars of switchgrass like ‘Heavy Metal’, ‘Warrior’, and ‘Prairie Sky’. Some sedges may develop Pythium root rot if overwatered.

Weed Control

Weed control can be a bit tricky in grass stands because it is difficult to identify weedy grasses from the grasses you planted intentionally at the beginning of the season. Additionally, many herbicides are made to kill grasses and monocots (Meyer 2012). You can prevent weeds in between plants by using mulch. Also, weedy cool seasons such as quack grass will start growing early in the spring. If quack grass seedlings sprout near a dormant warm season grass, nonselective herbicides can be applied in early spring to kill cool season grass weeds without harming the desired warm season grasses. However, weedy grasses, like quackgrass, may often start growing within an ornamental grass clump. Quackgrass has extensive rhizomes that are difficult to remove. In addition to removing any visible stems, quackgrass can grow from small pieces left behind after weeding. If the problem persists, digging the plants followed by careful examination of the different grass roots may be necessary. If the weedy grass roots are totally entangled with the desirable grass, you might have to discard everything and purchase new weed-free plants.

Careful observation of your plants is the best defense against unwanted weeds. Weeds are always easiest to remove when they are small.

Self-Seeding

Some species and nativars of native grasses are competitive and self-seeding, and so require management in a garden setting. Two of the most aggressive are switchgrass and river oats. River oats may be marginally hardy in zone 4 gardens, but will often self-sow and grow from new seedlings each year.

To manage self-seeders, keep an eye out for seedlings and control with hand weeding or selective herbicide. If any grasses become problematic from self-seeding, seedheads can be removed before the winter. Self-seeding characteristics of each grass are listed in the Chapter 3. For more information about self-seeders, check out this article in the University of Minnesota Extension Yard and Garden News by Mary Meyer.

A displacement of a stem from its upright position.

Refers to the zones in the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map used to determine which plants are likely to thrive in a certain location. The map is based upon average annual extreme minimum temperatures, divided into 10-degree F zones.