8.4 Sex: It’s About the Gametes

As you may have realized working through the previous two sections, attempting to find a distinguishing characteristic that can be universally applied across sexually reproducing organisms is challenging! But, biologically speaking, the distinction is quite simple—sexes can be distinguished, across the board, by gamete (sex cell) size.

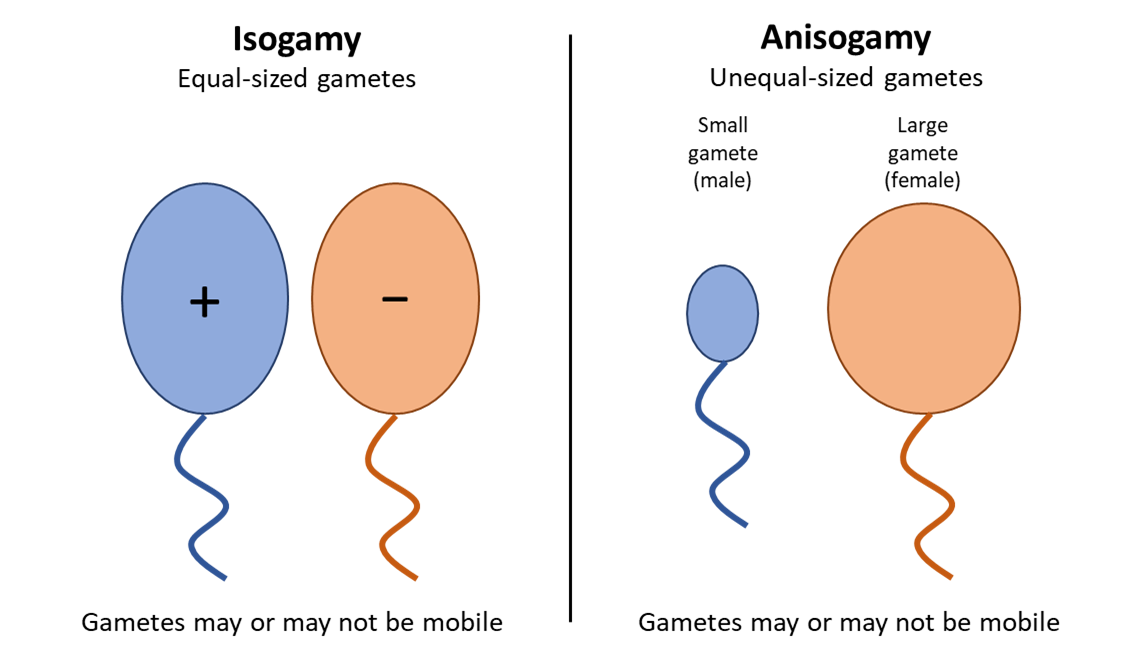

Some sexually reproducing organisms are isogamous, meaning they produce the same size gametes, and some are anisogamous, meaning they produce different size gametes. (“Iso” means equal, and “aniso” means not unequal.) Isogamous organisms include species of fungi, algae and protozoa; some of these organisms have between 2 and thousands of “mating types” that can be thought of as sexes. In those isogamous organisms, we don’t call those sexes “male” and “female”; typically we use other identifiers.

Note: In humans there are people who produce eggs and are often assigned female at birth, but do not identify as women. Their gender may be male, nonbinary, or another gender identity. There are also people who produce sperm and may be assigned male at birth, but do not identify as men. People can also have intersex characteristics — chromosomes, reproductive organs, or other anatomical traits that don’t fit into the binary male/female categories. Please see Section 8.7 for further discussion of variation in sex characteristics and Section 8.10 for further discussion of gender.

While sexually reproducing plants and animals generally have only two sexes, our ability to define individuals as one sex or the other is complicated by our growing understanding of the sex varieties that exist. You can read here about some fascinating examples of our changing understanding of sex.

Check Yourself