10.6 Monogamy

Monogamous species are characterized by two individuals pairing together for at least one breeding season. The prefix “mono” means one. Juveniles in these species typically require parental care from two individuals, and both males and females invest about equal amounts of energy into their offspring. Typically the environment in which this arises has scattered, non-defensible resources, and family units will group together. The evenly divided parental care allows for overall more care towards offspring, and high offspring survival rates. Because it is more clear who the parents of the offspring are, there are fewer instances of infanticide. Additionally, it is guaranteed that most adults will have the opportunity to reproduce.

Extra-Pair Copulation

Due to advances in DNA sequencing, scientists have discovered that many species considered to be completely monogamous had instances of extra-pair copulations. There is a difference between social monogamy and genetic monogamy. In social monogamy, a male and a female stay together and interact socially, but also mate with other individuals. In genetic monogamy, a male and a female only mate with one another. Whereas in genetic monogamy it is evolutionarily favorable for a pair to only mate with each other, social monogamy means a pair may copulate with outsiders in order to increase genetic variability, but the pair will raise the offspring together, despite the fact that the offspring may be unrelated to one of the individuals. Interestingly, species that are genetically monogamous are extremely rare – some biologists think there are none. In other words, nearly all monogamous species engage in extra-pair copulations.

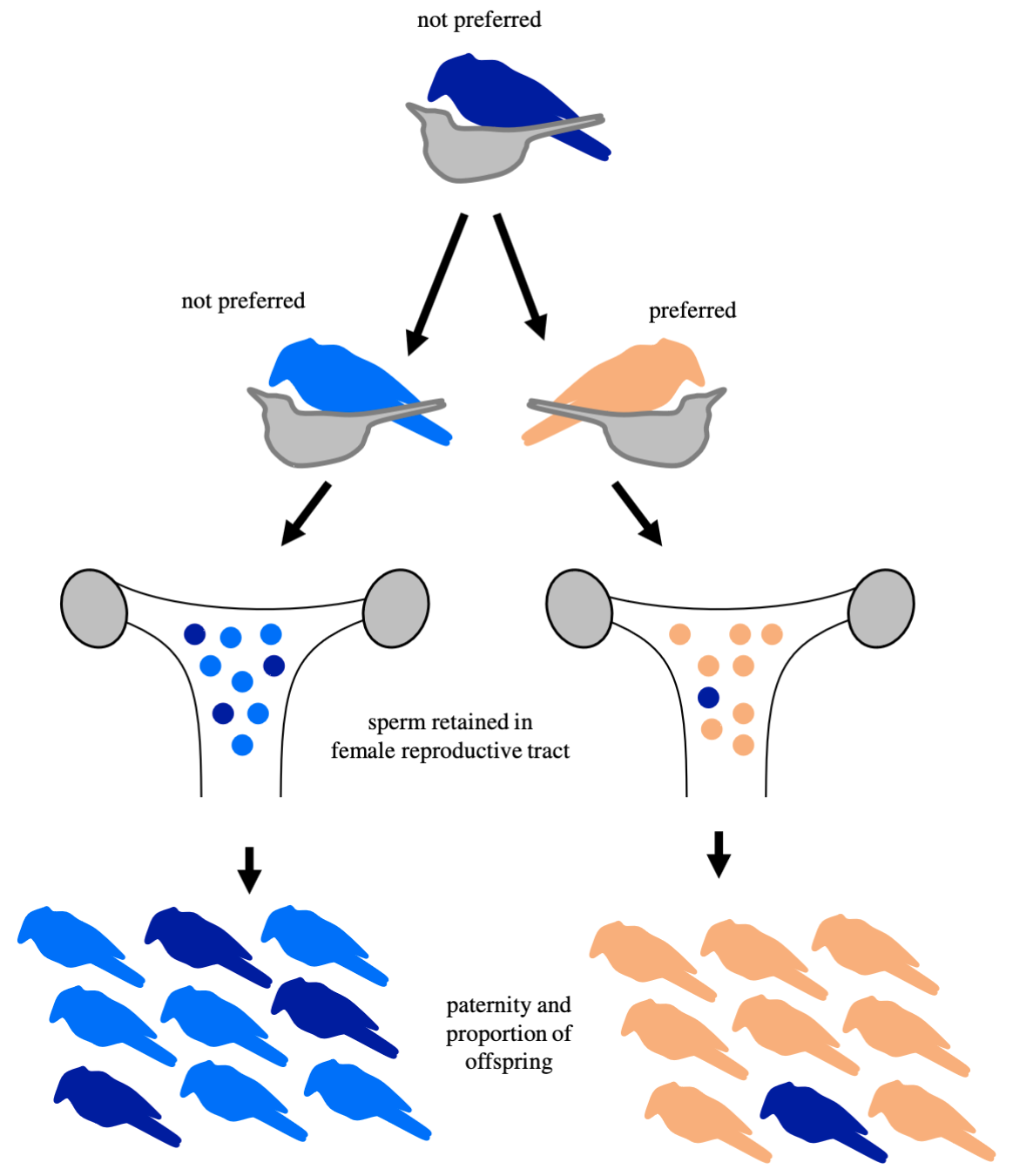

Depending on the genetic compatibility of a pair, female birds can have a variable ratio of offspring related to different males, as seen in the figure to the left. She “chooses” which sperm to use to fertilize her eggs, which is called cryptic female choice. This allows for increased genetic variation in her offspring and higher genetic quality offspring, improving her fitness.

Many animals that at first glance seem to be genetically monogamous actually have most matings outside of the pair bond. For example, some birds have only a small percentage of their offspring with their pair-bonded partner.

Prairie voles and vasopressin

A very well-studied monogamous mammal is the prairie vole, whose unique neurobiology lends us a better understanding of the proximate mechanisms of pair bond formation. (Remember, proximate refers to explanation of “how” a trait comes to be, while ultimate explanations explain “why” in evolutionary terms.) In this species, males and females form extreme pair bonds for extended periods of time, sharing a nest, co-caring for young, and even exhibiting empathetic behaviors toward each other. Recently, studies have shown that this may be due to the species’ high number of vasopressin receptors. Vasopressin is a common hormone found in the majority of animal species worldwide. Until recently, it was considered to only play a major role in kidney function and some other physiological functions, but with new studies emerging, it has been found to play a similar role as oxytocin (“the cuddle hormone”) in some species, helping to form pair bonds. Compared to the promiscuous meadow vole, prairie voles have a very high concentration of vasopressin receptors, especially in the parts of the brain that control the reward system. Because of this, it has been suggested that the vasopressin released by the pair cuddling together strengthens their bond. This strong pair bond is still being studied, especially with regard to how this concept may relate to other species, such as humans.

If you are interested in learning more about this concept, check out this article from February 2023.

- Figure from Moehring, A. J., & Boughman, J. W. (2019). Veiled preferences and cryptic female choice could underlie the origin of novel sexual traits. Biology Letters (2005), 15(2), 20180878–20180878. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2018.0878 ↵

- Image from Todd Ahern. CC BY 2.0 DEED ↵