1.3 Experimental Design

Because your hypothesis is testable you should be able to make a prediction, an outcome we would expect to see if our hypothesis is correct. A prediction should clearly state the type of evidence that will support our hypothesis.

For example, one hypothesis to explain why animals masturbate is “Sexual pleasure is a motivational system for both non-reproductive sexual behavior like masturbation and also reproductive behavior, penile-vaginal intercourse.”

A prediction arising from this hypothesis could be “individuals that masturbate more frequently are more likely to have had penile-vaginal intercourse.” With this prediction, you can get a good idea of how to test the stated hypothesis.

An experiment is a procedure done in a controlled manner for the purpose of addressing a stated hypothesis. We’ll discuss and conduct many experiments in class and lab during this course. You will want to keep as many factors as possible the same, to focus on those things that interest you. These factors that you keep identical between your experimental and control group are the controlled variables.

Scientists often have both experimental and control conditions. For example, you could compare frequent masturbators (the experimental group) to individuals that have not masturbated in the past year (the control group). Your experimental group should experience the dependent variable (e.g. a new medication, new classroom intervention, or in this case masturbation). While your control group is a baseline for comparison.

To focus on the relevant factors you should consider which controlled variables are important. For example, you may only include heterosexual individuals. Additionally, cultural and religious norms impact human perceptions about masturbation. Therefore, comparing individuals with similar backgrounds will make your analysis easier–for example, people of similar ages, raised in similar situations, and with similar religious backgrounds.

Points to Ponder

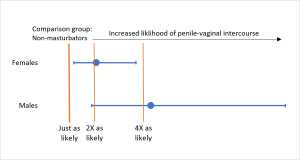

Cynthia Robbins et al. wanted to assess the prevalence and frequency of masturbation and whether it is associated with partnered sexual behaviors[1]. They collected data on adolescents ranging between 14-17 years old. Information regarding race/ethnicity, grades in school, annual household income, geographic region of the United States, rural vs urban, sexual orientation, and relationship status were all collected from the study participants. Collecting this information allows researchers to control for variables that might impact the outcome of their research, but is not their primary focus. Controlling these variables through careful study design helps researchers focus on their primary question.

After identifying and controlling certain variables you are ready to test your hypothesis. Robbins et al. surveyed their participants for prevalence and frequency of masturbation. Response options were “never”, “a few times per year,” “a few times per month,” “2-3 times per week,” or “4 or more times per week.” They also asked their participants whether they had penile-vaginal (penis in vagina) intercourse in the past year.

If frequent masturbators are more likely to have had penile-vaginal intercourse, then you have support for (but not proof of) your hypothesis. This one hypothesis is open to a variety of predictions, and each prediction can often be tackled in several ways.

We’ll use the terms independent and dependent to describe variables in our studies. The independent variable is the one that is manipulated, or varies as part of the study design. It is the variable that is purposefully different between your two groups. How frequently an individual masturbates could be an independent variable in the example above—you aren’t necessarily manipulating this variable, but you are collecting these data as a way to test the stated hypothesis.

The dependent variable is a factor that may change as a result of changes in the independent variable. The dependent variable is measured to see if the change in the independent variable had an effect. In the above example, presence of penile-vaginal intercourse is the dependent variable, and we have predicted that it will be more likely to have occurred in those who have masturbated.

Scientists employ many tactics for interpreting the data they collect. One way is to turn that data into figures. Let’s find out whether the data from Robbins et al. support the hypothesis “Sexual pleasure is a motivational system for both non-reproductive sexual behavior like masturbation and also reproductive behavior, penile-vaginal intercourse.”

Points to Ponder

Content on this page was originally published in The Evolution and Biology of Sex by Sehoya Cotner & Deena Wassenberg and has been expanded and updated by Katherine Furniss & Sarah Hammarlund in compliance with the original CC-BY-NC 4.0 license.

- Robbins CL, Schick V, Reece M, et al. Prevalence, Frequency, and Associations of Masturbation With Partnered Sexual Behaviors Among US Adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(12):1087–1093. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.142 ↵