10.8 Human mating systems

There are many ideas about human mating systems, varying from culture to culture. While some cultures hold the ideal that monogamy is the best mating system for humans, others strictly believe in polygyny, while others yet practice polyandry or promiscuity within their culture. These ideas raise the question: Which mating system would be most favorable to humans based on our biology? The answer can vary between different populations, especially as humans cover the globe, leading to adaptation to a diverse range of environments.

To better understand our species’ history we often use fossil evidence to understand the traits of our ancestors, but unfortunately behaviors are not preserved. To understand our ancestors’ behaviors we instead study our closest relatives who may have behaviors similar to our last common ancestors. From these observations, we can start to piece together how and why certain behaviors arose in humans. When discussing the ancestral human mating system, we usually are referring to what may have been the mating system of our hunter-gatherer ancestors that lived around 12,000 years ago, or earlier.

Our closest relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos, live in promiscuous groups (as discussed in Section 10.5). We know that early humans lived in small groups, leading many to believe that perhaps our ancestors exhibited similar mating behaviors as these species. In 10.4, we discussed the polygynous behaviors of gorillas. Because gorillas are another close relative of our species, some hypotheses suggest that the ancestral state of our species was similar to the polygynous structure of gorilla societies.

The mystery of ape testes

A comparison of great ape genitalia can shed light upon human mating systems. The great apes include gorillas, orangutans, chimpanzees, bonobos, and humans. The great apes are unified by several shared derived traits, including bone structures that enable us to walk upright (although the non-human apes can only do so for a few steps at a time), opposable thumbs, three-dimensional vision, and large brains. We differ, however, in several features, including our mating habits.

Male gorillas fight amongst themselves—sometimes to the death—for dominance in a community; the dominant male then enjoys a harem of sexually available females. Chimpanzees are promiscuous, with both males and females copulating with several other chimpanzees in a single day. And then there are the humans, exhibiting various mating strategies (from harem-building polygyny to serial monogamy to life-long monogamy) that appear to be somewhat dependent on culture. But what was the original human mating system? Did we come from an ancestral human that was monogamous, promiscuous, polygynous, or somewhere in between?

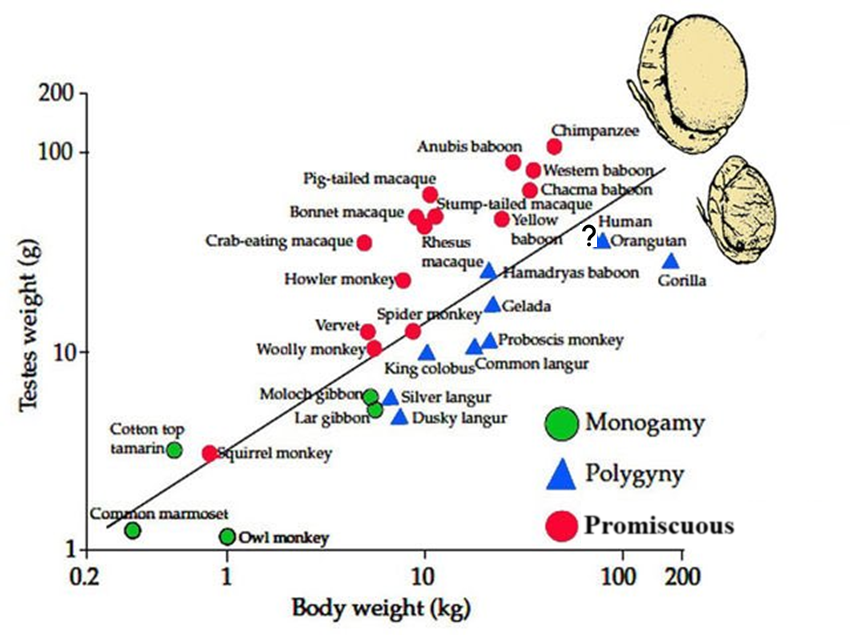

A clue may lie in the testes, where sperm are produced in a sac-like scrotum hanging outside of the male’s body. Mammals display considerable variability in the ratio of testis weight to body weight. For example, within bats, testes volume varies greatly among species: the yellow-winged bat’s testes make up only 0.11% of the bat’s total body mass; in contrast, the Rafinesque’s big-eared bat has testes that make up 8.38% of its body mass (with that testes size why is it called the big-eared bat and not the big-testes bat?) In the great apes, chimp males have the largest testes, relative to body size; gorillas have the smallest (Figure 10.11).

For the promiscuous chimps, large testes may be mandated by sperm competition, whereby males must compete, through their sperm, for access to the female’s limited supply of eggs. If a female mates with several males, each individual male is thrust into competition with the others, and no male can compete without an ample supply of sperm. This demand for more sperm is met by larger testes. Sperm from gorilla males, on the other hand, do not need to compete with sperm from other males. Once a male gorilla has established dominance and secured a harem of available females, no other males are mating with the females, therefore reducing the advantage of producing huge quantities of sperm. A reduced demand for sperm appears to have resulted in smaller testes.

Human males have testes that, relative to body weight, sit somewhere in between those of the gorilla and those of the chimpanzee (see question mark on Figure 10.11). What does this intermediate testes size tell us about our ancestral mating habits? We certainly don’t appear to have been as promiscuous as the chimps, but we probably can’t rule out sperm competition altogether. Human testes size, together with other evidence of our evolution, suggests that our ancestral mating system may have somewhere in between promiscuity and polygyny/monogamy (note that testes size cannot distinguish between polygyny and monogamy because both have no to little sperm competition). Perhaps we have been largely monogamous, with low—but significant—levels of extra-pair copulation (or “cheating”).

Interesting tales of ape genitalia don’t end with the testes. The human penis is remarkable in being much longer, relative to body size, than the penis of the other great apes. An interesting observation is discussed further in Chapter 9.9.

Overall, the topic of human mating systems can be controversial with such a small record of how early humans lived. Today, with humans distributed across the globe, there are many different cultures with unique social structures, some more similar to monogamy, others polygyny, and others yet promiscuity and polyandry. Certain human traits can give us insight into the ancestral state of our species, but we must keep in mind that within this subject, there is much room for gray area, with many species, including our own, not fitting perfectly into a specific system.

Check Yourself

- Figure modified from: Harcourt, A. H., Harvey, P. H., Larson, S. G., & Short, R. V. (1981). Testis weight, body weight and breeding system in primates. Nature (London), 293(5827), 55–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/293055a0 ↵