2.0 Introduction

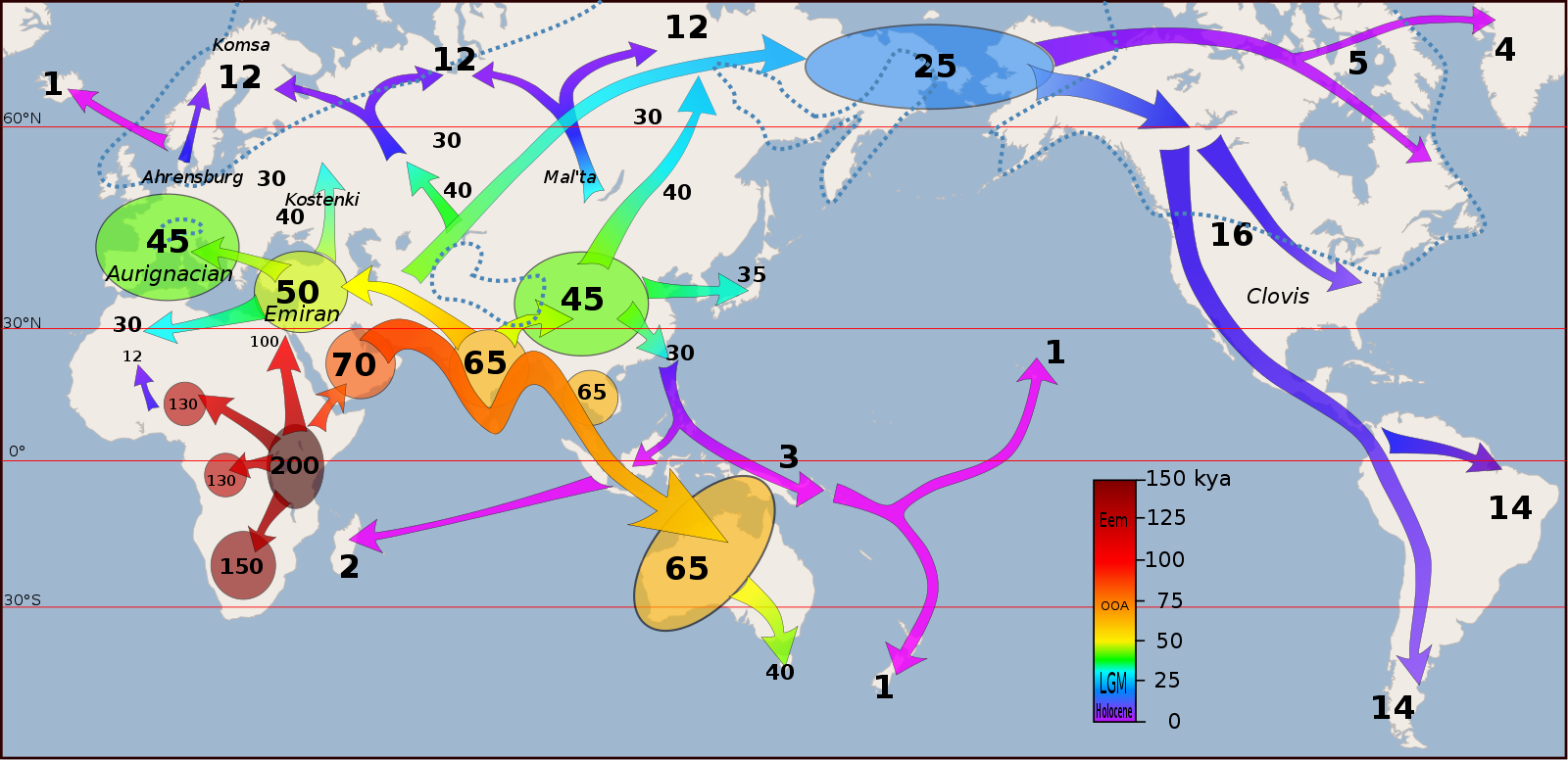

Evolutionary biologists and paleontologists estimate that anatomically-modern humans (Homo sapiens) appeared around 300,000 years ago. Compared to our closely related and now extinct “cousin” species like Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis, Homo sapiens have larger brains, more slender bones, and smaller brow ridges, among other differences. Since our first appearance in Africa, humans have spread across the globe in many waves of migration, creating the amazing diversity that we see today (Figure 2.1).

Are humans still evolving? One might think that the answer is no. Modern medicine and hygiene practices often allow us to survive despite illness and other threats to our survival and reproduction. Because of agriculture and technology, most people don’t need to spend time and energy hunting for their food or avoiding predators. We have altered our environments to our advantage, perhaps lowering the need to adapt to environmental conditions.

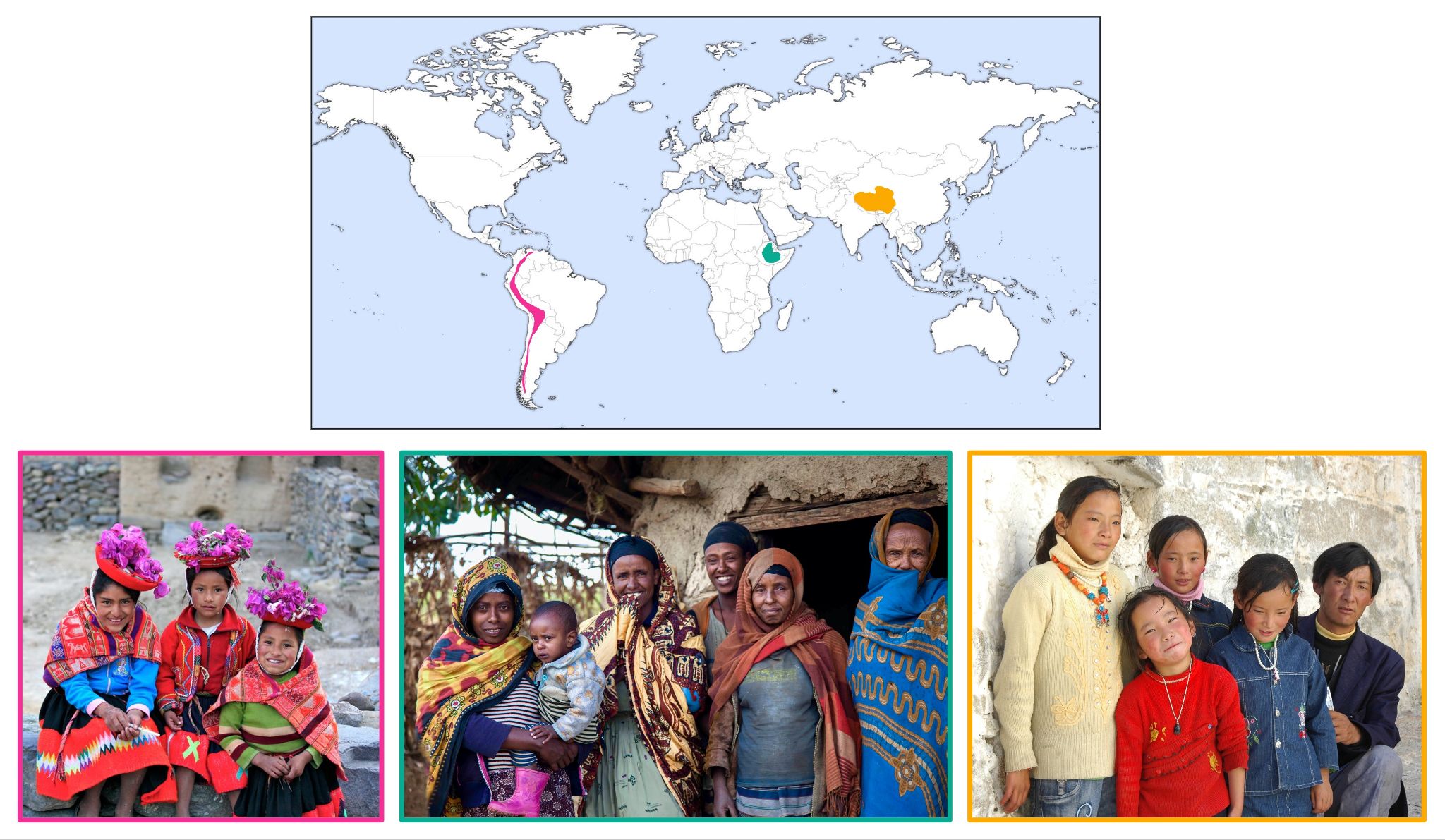

However, environmental features differ greatly across the planet, and extreme environmental conditions still pose evolutionary pressures. For example, in three locations in the world there is a very strong environmental challenge. In the Tibetan Plateau, people live between 3000 and 4500 meters above sea level–that’s between 9,000 feet and 14,800 feet. For comparison, a mile is 5,280 feet, and the city of Denver, Colorado is almost exactly at that altitude. That means that Tibetan people live between 1.7 and 2.8 miles above sea level – an astounding height. In the Andes mountains of South America, populations of humans live between 2500 and 4500 meters. In the Ethiopian Highlands in East Africa, people live between 2500 and 3500 meters above sea level.

Living at such high altitudes poses many challenges. A major challenge is low oxygen. At 4000m, oxygen concentrations are 40% lower than at sea level. If you’ve been to any of these regions (or to the Rocky Mountains in the United States, like in the city of Denver), you may have experienced altitude sickness. At first, you may experience shortness of breath, nausea, and headaches due to brain swelling. After several days, some short-term changes in your body might help you cope, like temporarily higher hemoglobin concentrations and red blood cell counts. That’s why some athletes train at high altitudes—this short-term acclimatization helps them perform better in competitions at lower altitudes. However, for most people, long-term exposure to the low oxygen concentrations at high altitudes can result in many harmful conditions, like pulmonary hypertension (high blood pressure), high risk of pregnancy failure, and an increased risk of liver disease.

The potentially damaging long-term effects of high altitude do not affect people who live in the Tibetan Plateau, in the Andes Mountains, and in the Ethiopian Highlands (Figure 2.2). Tibetans have lived at high altitudes for at least 30,000 years and Andeans for at least 11,500 years. In Ethiopia, Amhara people have lived at high altitudes for 70,000 years, and Oromo people for 500 years. For the most part, people in these populations do not experience the harmful long-term effects of low oxygen concentrations. They have normal pregnancy success rates, low rates of liver disease, and high lung and heart function.

In this chapter, we will explore the processes and products of evolution. An understanding of evolution of evolution can allow us to answer questions like:

- How did adaptations to high altitude evolve?

- Are the adaptations the same or different across the three populations? Do they involve the same or different gene variants?

- Are humans still evolving?

Throughout the chapter, we will return to the example of adaptation to high altitudes and learn what evolutionary biology has to say about the evolution of our species.

- Image from Wikimedia Commons, created by :Dbachmann, under CC BY-SA 4.0 license ↵

- Map adapted from Figure 1 of Bigham, Abigail & Lee, Frank. (2014). Human high-altitude adaptation: Forward genetics meets the HIF pathway. Genes & development. 28. 2189-2204. 10.1101/gad.250167.114. ↵

- Image from Flickr, created by Richard Weil, under CC BY-ND 2.0 license ↵

- Image from Wikimedia Commons, created by Alex Proimos; under CC BY 2.0 license ↵

- Image from Flickr, created by the International Livestock Research Institute; under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license ↵