11.7 Testing Trivers-Willard in opossums

In the mid-1980s, two biologists devised a simple test of the Trivers-Willard hypothesis of sex-ratio allocation. Specifically, they trapped and marked (for future identification) 40 female Venezuelan opossums. They then supplemented the diets of 20 of these opossums, specifically by leaving a tin of sardines by their burrows every two days for several weeks. Then, they re-trapped the females, looked in their pouches (opossums are marsupials, meaning their young develop in pouches), and identified the sex of their offspring.

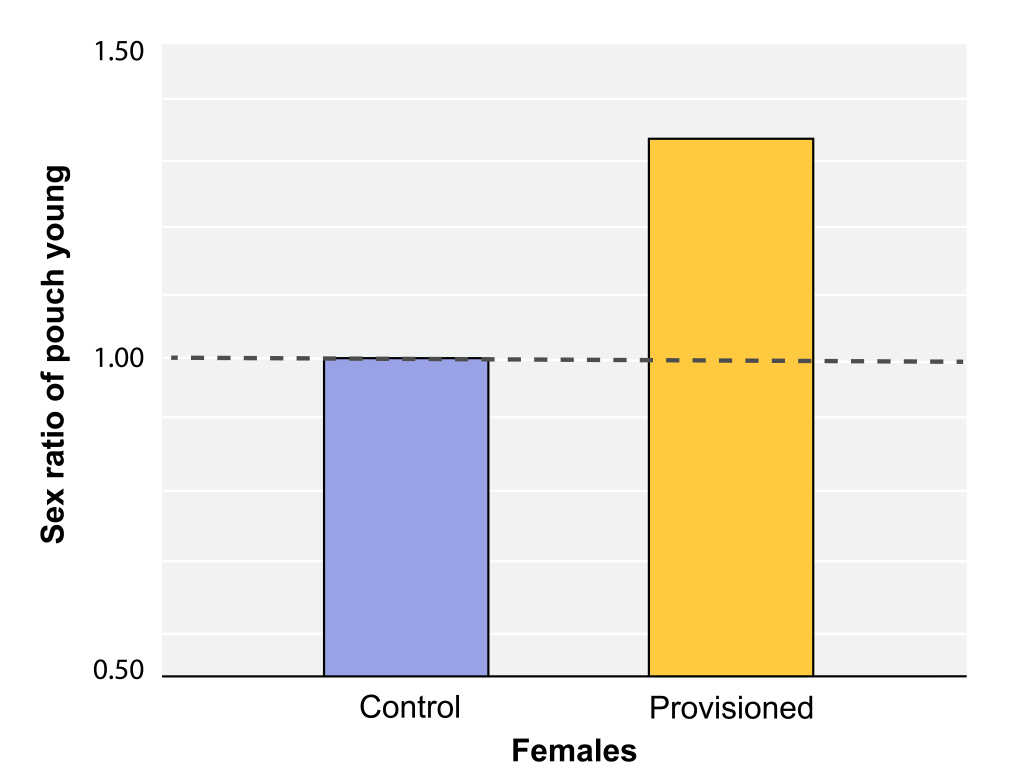

Their data are summarized below.

Check Yourself

Similar support of the Trivers-Willard hypothesis has been observed in similar studies with other organisms, but in some cases, these findings have not been observed. In some situations, explanations other than the Trivers-Willard hypothesis may better explain observed sex ratios. For example, in some organisms, males are bigger and demand more resources; it makes sense that a mother in poor condition would selectively miscarry males in favor of females.