1.6 Correlation Does Not Equal Causation

In the previous example, you may have selected “Oral contraceptive usage is correlated with cervical cancer”. This statement is accurate and does not imply that using the Pill necessarily leads to cervical cancer. Nor do we have any reason to think that Brinton’s study was flawed. She and her colleagues used a relatively large number of participants to look for trends, and did their best (using randomly generated phone numbers) to find a random sample for the control group. However, it is understandable that, when this study (and others like it) came out, many people were tempted to think that using oral contraceptives causes cervical cancer. These individuals were falling victim to the idea that correlation implies causation; this misconception is powerful and has created a lot of trouble for scientists.

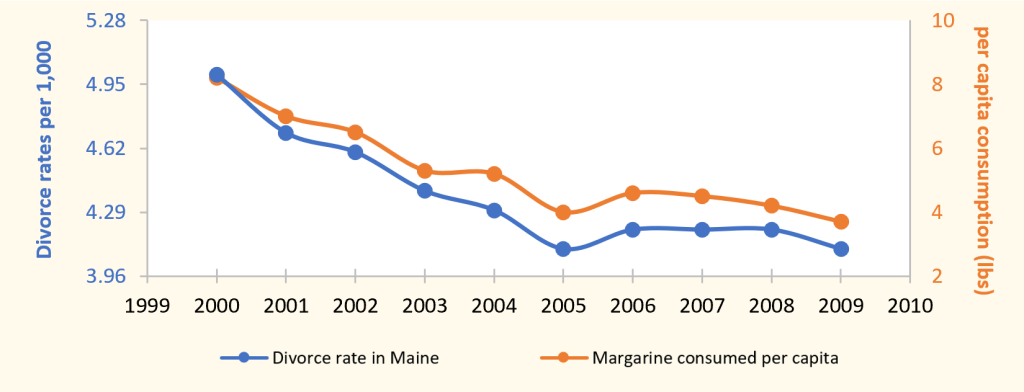

Note that some correlations are positive: increase in one variable is correlated with increase in the other variable. For example, there is a strong correlation between decreasing divorce rates in Maine and decreasing consumption of margarine (Figure 1.4):

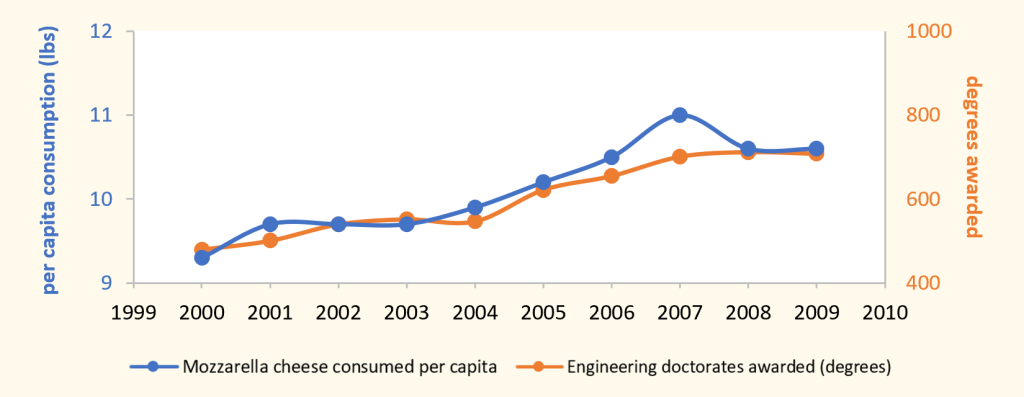

Note the source! The above two examples are from a [fun!] website called “spurious correlations,” so they aren’t meant to be taken seriously. However, the data are real.

Some correlations are negative, whereby an increase in one variable is correlated with a decrease in the other. The data above compare course absences in BIOL 1003 with percentage performance in the course.

Check Yourself

Content on this page was originally published in The Evolution and Biology of Sex by Sehoya Cotner & Deena Wassenberg and has been expanded and updated by Katherine Furniss & Sarah Hammarlund in compliance with the original CC-BY-NC 4.0 license.