1: Preparing a Woodland Stewardship Plan

1. Preparing a Woodland Stewardship Plan

John G. DuPlissis, Silviculture Program Coordinator, University of Minnesota Natural Resources Research Institute

Melvin J. Baughman, Extension Forester, Retired, University of Minnesota

Eli Sagor, Extension Specialist, University of Minnesota

Reviewed and revised in 2019 by Michael Reichenbach and John Duplissis

What will you do with your woodland? Decisions you make now about your woodland, wildlife management, harvesting trees, or controlling invasive species will influence the character of your woodland for many years into the future. As a woodland owner planning for the long term is important because whatever you do—or don’t do—will have long-term effects on your woodland.

Planning for the long term is a process that involves many steps. We present a planning roadmap for you to use to develop a woodland stewardship plan. A woodland stewardship plan builds on your goals, and incorporates the knowledge and experience of a forester and other natural resource professionals in predicting the future condition of forest stands, and setting management objectives. This process is repeated regularly, typically once every 10 years.

What Is a Woodland Stewardship Plan?

A woodland stewardship plan typically is a written document that:

- Clearly states why you own your property and your management goals.

- Is tailored to help you meet your goals within the capability of the land.

- Is based on a clear understanding of ecological processes.

- Offers recommendations for sustainable forest management practices.

- Provides a timetable for carrying out the forestry practices needed to reach your objectives.

Many woodland stewardship plans:

- Incorporate publications or other attachments to describe forest management practices and inform you about sustainable forest management.

- Explain where you can get help to follow through with the plan.

Creating a woodland stewardship plan is easier than you might think. A forester can do most of this work for you.

Work with a Forester and other Natural Resource Professionals

Forestry is a science that requires an understanding of how trees grow, reproduce, and respond to changes in the environment. Foresters have a knowledge of forest ecosystems and processes and have experience in managing forests. Depending on your interests and resources, you may also need to work with other experts in fields such as wildlife, soil, water, and recreation. Your state department of natural resources and some soil and water conservation districts have foresters available to visit your woodland, answer your questions, and help you prepare a woodland stewardship plan. Private consulting foresters are independent contractors who help landowners prepare woodland stewardship plans, market timber, plant trees, or perform any other management practices. Forest products companies employ foresters to buy timber from private lands. Some of these foresters also write management plans for woodland owners.

Sources of Technical Assistance

Service Foresters

Many forestry state agencies (e.g., Department of Natural Resources) have professional foresters on staff which are available to visit your land and answer any questions that you might have. The role of these service foresters is to motivate and guide woodland owners to practice sustainable forestry. Service foresters make “woods” calls with personalized, individual service, and they administer a number of planning, property tax incentive and cost-sharing programs.

Private Consulting Foresters

Private consulting foresters are independent contractors that perform technical forestry work on a fee or contract basis for work they do. Private consulting foresters provide a wide range of woodland management services.

Industry Foresters

Many forest products companies employ foresters to work with private woodland owners to procure timber from your woodlands. Many companies will provide management services in return for the right to bid first on your timber when you are ready for a harvest.

Forest Stewardship Plan Basics

The six steps that follow are designed to guide you through the forest stewardship planning process.

1. Identify Your Goals

The first step in developing a stewardship plan is to identify your woodland goals. A goal is a statement specifying what you want to achieve. Work with a forester to identify your SMART goals. A SMART goal can increase the likelihood of success and helps you identify:

- Where you are and where you want to go.

- How you intend to get there.

- When you intend to arrive.

SMART is an acronym, each letter helping you keep your goals focused:

S – Specific

M – Measurable

A – Attainable

R – Relevant

T – Time bound

A goal might help you answer the following question, “What outcomes do you seek from owning your woodland?” Your goals provide direction for your actions and the management or care of your woodland. An example of long term SMART woodland goal is:

Start with a list of long term goals, ask your family and the other owners of your property to individually develop their list of goals, then meet with them to blend your lists into one. Finally, prioritize your goals. Review your list of prioritized goals with your forester and natural resource professional; ask them if your goals attainable and relevant to your woodland? Your natural resource professional will also help you develop short term goals and management actions that will become part of your stewardship plan. Worksheets for goal setting are included in the online resources.

Sharing a list of clear, specific goals and objectives with a forester provides a guide for them to recommend appropriate management practices for you.

2. Inventory and Evaluate Your Property

Begin by having accurately property boundaries and marking them with a fence, paint marks on trees, rock piles, stakes, or other means. Clear brush from your property lines to avoid trespassing when you or your neighbors carry out forestry practices. If the boundaries are not clearly identifiable, you may want to have your land surveyed.

Gather historical facts concerning previous land use or management activities that have influenced the development of your woodland. Such activities might include livestock grazing, agricultural cropping, timber harvesting, tree planting, fires, and pest outbreaks. Foresters use information about these events and their timing to analyze the development of existing woodlands and to predict the results of future management practices.

With this information and other information that your natural resource professional has the following can be developed.

A written woodland stewardship plan may also include these components:

- Your name and contact information.

- Legal description of the property.

- Your management goals.

- Description of the ecosystem in which your property is located and ecological issues of local concern.

- Inventory of known or potential historic and cultural resources (for example, cemeteries, burial mounds, foundations). Your forester may be able to obtain this information from a state-wide database of such resources.

- Inventory of known or potential threatened, endangered, or special interest species that are or may be present on your property. Your forester may be able to obtain this information from a statewide database of such species.

- History of your property’s management.

- Property boundaries

- Woodland boundaries

- Land uses

- Roads and trails

- Utility wires, pipelines, or other rights-of-way or easements

- Buildings

- Water resources

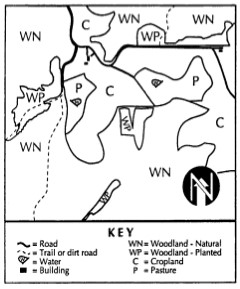

- Map or aerial photograph of the property (Figure 1-1, 1-2), approximately to scale, showing the following:

- Unique natural, historical, or archaeological resources

- Topography, and soil type maps, and interpretive information (Table 1-1) to help you determine the suitability of your land for different tree species, road or building sites, or other land uses. They may be available from local offices of the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service.

| Map symbol and soil name | Erosion hazard | Windthrow hazard | Common trees |

|---|---|---|---|

| 457G, LaCrescent, 45-70% slope | Severe | Moderate | Northern red oak, white oak, American basswood |

| 580B, 580C2, Blackhammer-Southridge 3-12% slope | Slight | Slight | Northern red oak, white oak, American basswood, shagbark hickory |

| 580D2, Blackhammer-Southridge 12-20% slope | Moderate | Slight | Northern red oak, white oak, American basswood, shagbark hickory |

- An inventory of woodland resources such as:

- Location of timber stands.

- Estimates of timber quantity, quality, size, product potential, regeneration potential, and other characteristics by species and stands (A stand is an area of woodland [usually 2 to 40 acres] that is sufficiently uniform in its tree species composition, spacing, and size; topography; and soil conditions that it can be managed as a single unit. Management practices such as planting, thinning, and harvesting are carried out more or less uniformly across a stand [Figure 1-3].)

Figure 1-3. Two stands: a natural hardwood stand in the upper right and young conifer plantation in the lower left (photo: Oregon State University). - Site factors affecting tree growth including soil depth, texture, moisture, fertility, and chemical properties, and landscape position (such as north or south slope, ridge or valley).

- Location of trails, roads, and equipment landings.

- Water resources including perennial and intermittent streams, lakes, wetlands and seasonal ponds, seeps, and springs.

- Location of stream crossings.

- Wildlife habitat (including location and quality of food, cover, water, breeding, and nesting sites for significant wildlife species or groups of species.

More detailed descriptions of timber inventory procedures are presented in Chapter 2: Conducting a Woodland Inventory.

3. Develop Stand Objectives and Management Alternatives

An inventory shows the current condition of your woodland. A forester can use the inventory to predict the future development of each stand by considering:

- Which tree species currently dominate the overstory (overhead canopy of trees)?

- Which species are present in the understory (trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants beneath the overstory)?

- Considering site characteristics, which tree species show the greatest potential to dominate the site in the future? (A site is an area of woodland with relatively uniform growing conditions such as soil, moisture, and slope.)

- What undesirable tree species are currently competing for the resources on the site?

- How will the tree species that are present respond to different management practices?

- What damaging agents are present or likely to occur in the stand and how will they affect the stand in the future?

The science of forestry is the ability to predict and to control in some measure forest succession through the application of ecological principles and silvicultural techniques. By answering these questions your forester can come up with a series of alternatives that can help you meet your goals.

However, there are other and sometimes more important considerations that will guide which alternatives are acceptable and it is important that you work with your forester to consider which alternative is best for your circumstances. Some things that you need to consider include:

- The presence of archaeological, historical or cultural resources and/or threatened, endangered or special interest species on your property. State or federal law protecting these resources may limit opportunities in specific areas of your woodlands.

- Best Management Practices to preserve water quality and soil productivity, remove invasive species or limit the use of pesticides.

4. Assess Management Constraints

Consider these management constraints when choosing which practices to implement:

- The amount of time you have available to do the work.

- Your experience and expertise levels.

- The availability of skilled contract labor.

- The equipment available.

- Your financial limitations.

- The availability of government financial aid.

- The potential economic return, including the tax implications (see Chapter 14: Financial Considerations).

- The presence of cultural resources and threatened, endangered, or special interest species that are regulated by state or federal law.

- The zoning laws or forest practice regulations in effect in your area.

- The prevailing attitudes of neighbors or the general public.

5. Choose Management Practices and List Them on a Schedule

Prepare an activity schedule, covering at least five to ten years, that lists management practices and the approximate dates when they should occur. If your woodland is large—perhaps several hundred acres—activities may occur every year. If it is smaller, management activities may occur less often, perhaps only once every ten years. Regardless of its size, inspect your woodland at least annually. Walk through the woodland and look for damage by pests, fire, or wind, unauthorized harvest, damaged fences, and soil erosion.

6. Keep Good Records

It will be easier to update your woodland stewardship plan and make sound decisions about the future when you keep accurate records of what you have done. Records also will be important when filing income tax returns, selling property, or settling an estate. Management records may include:

- Management plan

- Timber inventory

- Management activities accomplished (what, when, where)

- Sources of forestry assistance (name, address, telephone, e-mail addresses and web sites)

- Association memberships

- Suppliers of materials and equipment

- Contracts

- Insurance policies

- Forestry income and expenses

- Deeds and easements

Passive Management

Some landowners choose to “let nature take its course” on their woodland property. This is a conscious decision that these landowners make thinking that nature, left to its own devices, will be a better manager than they could ever be. While this may be true, many of the natural processes that formed today’s forest have been impaired by human activity and the introduction of non-native plants, animals, insects, and diseases. Therefore, passive management requires as intense a commitment to learning about your woodlands and being an active steward of your land. Allowing nature to take its course requires that you have an understanding of natural processes and forest ecology and the consequences of how not taking any action will impact your forest for better or for worse.

Summary

Your woodland stewardship plan is a living document that you can refine as you learn more about your woodland and its capabilities, or as your needs change. Revise your plan at least once every 10 years.