9: Harvesting Timber

9. Harvesting Timber

Charles R. Blinn, Extension Specialist, University of Minnesota

Angela S. Gupta, Extension Educator, University of Minnesota

Reviewed and revised by the authors in 2019

A timber harvest should be designed to help you accomplish your management objectives. Therefore, decisions such as the location of roads and in-woods skid trails, the specific equipment selected, what to do with limbs and tops and where processing occurs all should relate back to those goals.

Most timber harvesting is done by professional loggers who have the equipment, knowledge, and experience necessary to conduct an effective and safe operation. The work and time your forester spends in planning your timber harvest will reward you with higher profits, a better quality residual stand, and protection of the environment.

Select trees to cut based on your management objectives, stand conditions, and the silvicultural principles described in Chapter 6: Managing Important Forest Types. Local or temporary market opportunities may play a role in the timing or design of your sale. This chapter provides basic information on the harvesting process, including safety, forest management guidelines, the infrastructure needed to create access to and within a timber stand, harvesting equipment, and harvesting systems. Your forester will be able to help design the harvest to fit your management objectives.

Safety

Logging is one of the most hazardous occupations in the United States. Loggers should follow standard safe logging procedures. Have a conversation with the logger to learn about their safety practices. When you visit an active logging site, remain visible to the operators, wear a hardhat and bright colored clothing, stay away from equipment when it is operating, and avoid going near any trees that are leaning. Do not speak with anyone operating equipment until the person has stopped the machinery and signaled that it is safe to approach.

Timber Harvesting Guidelines

Timber harvesting operations can affect a number of factors within your forest, including:

- Cultural resources such as historic structures, cemeteries, and archaeological sites.

- Riparian areas.

- Plant and animal species of special concern.

- Soil productivity.

- Visual quality.

- Water quality and wetlands.

- Wildlife habitat.

To manage those effects, states have developed best management practices and forest management guidelines. Incorporating appropriate guidelines into your timber sale contract can help facilitate the sustainability of forest resources. Avoid including inappropriate guidelines because they may reduce interest from potential buyers. Your forester will be able to recommend appropriate guidelines for your timber harvest.

Timber Harvesting Systems

Descriptions of three basic timber harvesting systems—whole-tree or full-tree, tree-length, and shortwood or cut-to-length—follow. The systems differ in terms of the amount of processing that occurs at the tree stump and the form in which wood is transported to the landing for further processing or transport to the mill. One harvesting system may be better suited for accomplishing your objectives than others.

- Whole-tree or full-tree. In this system, the entire tree—including the stem, limbs, and top—is dragged to the landing with a skidder or horse. This system removes the maximum amount of material from a site. It also facilitates moving tops and limbs to the landing for processing, burning, or firewood production. However, because the entire tree is taken to the landing, residual trees may be damaged and a larger landing is needed to handle the size and volume of material.

- Tree-length. In this system, trees are felled and the top and limbs are removed before the trees are dragged to the landing with a skidder or horse. By leaving limbs and tops at the stump, this system retains nutrients at the stump.

- Shortwood or cut-to-length. In this system, the tree is felled, the top and limbs are removed, and the tree stem is bucked (cut) into individual forest products (such as pulpwood and sawtimber) at the stump area. The shorter product lengths allow a forwarder to move in tight areas and to carry wood to the landing. The forwarder may drive on slash mats, reducing soil compaction. A smaller landing is required in this system than in the other two.

Transportation Infrastructure

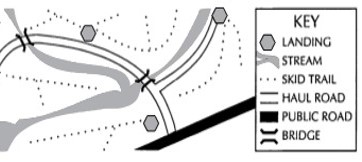

Few harvesting decisions have a longer lasting impact than the design and construction of haul roads, skid trails, and landings (Figure 9-1). Haul roads usually are permanent roadways that provide access for trucks to specific points in the woodland for hauling logs or other management purposes. Skid trails generally are temporary, unimproved roadways that enable skidders, forwarders or horses to transport logs from the interior of the woodland to the landing. Landings are areas used for processing (such as sorting products, delimbing, cutting logs to shorter lengths, and debarking) and for loading timber products onto trucks.

The general goal is to minimize the amount of infrastructure and environmental impacts (such as soil erosion) while still achieving your land management goals.

While roads, skid trails, and landings are generally constructed by loggers, landowners should understand the basic processes and standards. When planning new infrastructure, locate it in areas that facilitate your long-term ownership goals and plans.

The layout of transportation infrastructure is influenced by property lines, topography, soil conditions, streams and wetlands, economic limits on skidding distances, and other factors. Permits may be required for stream and wetland crossings, culvert installations, driveway access, and other road work.

The potential for soil erosion and stream siltation is especially pronounced in areas with steep slopes and erodible soils. To reduce soil erosion avoid building roads and skid trails that run directly uphill or downhill and mininize the amount of soil exposed. Use water diversion systems that move water off the exposed soil surface or away from ditches into the vegetated forest floor. Because water diversion options may impede some recreational uses of roadways, discuss their design with your forester.

Revegetate roads, skid trails, ditches, and landings with grasses and forbs (any herb other than grass) to help prevent erosion. The seed mix and application rate will vary according to your climate and soil. Native seed mixes are recommended to reduce the chance of introducing harmful invasive species. The seed mixture can include food and cover plants that are beneficial to wildlife. Where possible, lightly disk and fertilize exposed soil before broadcast seeding.

To protect roads and skid trails after logging:

- Keep ongoing travel to a minimum.

- Use them only when the soil can support the equipment without causing ruts.

- Inspect them periodically to make sure that water diversion structures (such as waterbars, ditches, and culverts) are working correctly.

Roads

Haul roads provide access for trucks to specific points in your woodland for hauling logs or other management purposes. In order to be able to support the weight of the trucks, roads are compact surfaces which aren’t designed to allow water infiltration. When locating a road, consider future access needs into the area, locate them to minimize the overall length and width of the road and use existing roads where possible and appropriate. Avoid crossing water and building on soils which won’t drain well (e.g., clay) where possible. Maintain vegetation between the road and water bodies so that runoff and sediment will filter into the soil before it reaches the water. Minimize the amount of soil exposed and make sure that water will be able to drain off the road away from water into a vegetated area.

Roads may be designed for short-term temporary use, seasonally permanent for long-term use when the soil is frozen or firm, or permanent for all-season use to support year-round access. In winter, it may be possible to create a temporary road across weak soils by helping frost penetrate the ground on cold days once the soil has been removed or by compressing it using a snowmobile or other vehicle with low ground pressure.

Skid Trails

Skidding is the process of transporting logs from the stump after trees are felled to a landing where they can be further processed or loaded onto trucks. Logs are usually dragged by a skidder or horse or carried by a forwarder, thus creating skid trails. These trails usually are not graded and need only a minimum amount of clearing. Skid trails should be designed to follow a relatively level route through the terrain, avoid wet areas and rock outcrops, be as straight as possible, and follow existing trails and openings wherever possible.

Depending on your management objectives and forest conditions, material may be skidded over a fixed trail network or the logger could use a different skid route for each trip to help knock down undesirable trees and shrubs, thus helping to clear the site for regeneration. Frozen or dry soil conditions are recommended to minimize soil compaction. If soils are not frozen, it is generally advisable to minimize the area affected by skid trails to avoid compacting the soils across a broad area of the forest. Your forester may be able to recommend additional techniques to minimize compaction.

Landings

Landings are busy places during a harvesting operation, because of processing which may occur and the loading of timber products onto trucks. Therefore, they have the potential to create big impacts on a relatively small area. Carefully select landing locations to provide for efficient timber removal and minimize adverse environmental impacts. Proper construction and maintenance of a landing is similar to that for roads.

Locate landings close to concentrations of timber. Choose locations that can be reused, are away from water and with a slight slope so that water will drain away from the area. Avoid steep slopes and low, wet areas where trucks cannot maneuver. Where feasible, locate landings below ridge crests to reduce the need for steep, hazardous roads. The haul road approaching the landing should have a low grade (not a steep slope) to make it easier for trucks to climb the slope and to reduce the movement of water into the landing area. Landing size and shape will be influenced by the timber length, processing to be performed at the landing, the need to store products on the landing prior to hauling, loading method, the need for an area to turn trucks around, and the type of hauling equipment. Consider creating a wildlife food plot on the landing after the harvest through use of appropriate seed cover.

Take special care when storing petroleum products and maintaining equipment in woodlands. Designate a specific place for draining vehicle lubricants so they can be collected and stored until being transported off-site for recycling, reuse, or disposal. Provide receptacles for solid wastes such as grease tubes and oil filters. Locate refueling areas away from water. A landing may be an excellent location for storing these products and maintaining equipment.

Cull logs and other debris may be a hazard to snowmobilers and other recreational users if left on the landing.

Harvesting Equipment

Harvesting equipment is generally designed to perform a limited number of tasks. Those operations described below may occur at the tree stump, during in-woods transport from the stump to the landing, or at the landing. While some logging businesses consist of one person who operates different pieces of equipment during the course of the harvest, others have several employees, each operating one piece of equipment. If possible, recommend that the logger power wash all equipment before taking it into the sale area. This may help reduce the spread of invasive or noxious weeds if seed is embedded in dirt or debris that may be clinging to the equipment.

Operations at the Stump

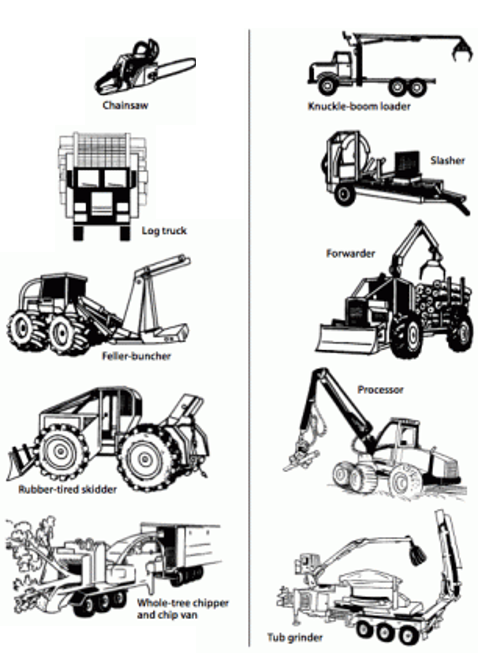

Operations at the stump always include felling the tree. Felling may be done by a chainsaw, feller-buncher, or a processor (Figure 9-2). After felling, the tree may be further processed by removing the limbs and top and by bucking (cutting) it into individual product sections. When material is being transported to a landing, the limbs and tops may be left at or near the stump to help avoid scarring remaining trees, if markets limit the use of this material or if the soil tends to be nutrient deficient. Removing the entire tree may be the preferred option where there are concerns about pest invasions after the harvest, when the whole tree will be processed at the landing, when the site will be planted after the harvesting operation has been completed, or to make it easier to cut firewood from the residue.

Transporting Material from the Stump to the Landing

Short logs, tree-length material, or whole trees may be transported from the stump to the landing either by skidding (dragging them on the ground) or forwarding (carrying them completely off the ground). Timber can be dragged to the landing using a rubber-tired or tracked skidder, farm tractor, or horse, or carried on a forwarder (see Figure 9-2). A rubber-tired skidder is lighter weight, less expensive, faster, and provides better traction over rocks than a tracked skidder. The tracked skidder, on the other hand, may compact the soil less, provide better traction in mud and slippery soils, and be less likely to create deep ruts. Wide tires on a rubber-tired skidder provide similar benefits to a tracked skidder.

Farm tractors are sometimes used for skidding, but they usually need modifications to become effective, safe skidders. A winch connected to the tractor’s power take-off (PTO) is an important asset. Some also require shields beneath their bodies to protect them from damage by high stumps and rocks.

Forwarding machines are equipped with a hydraulic loading boom and have a bunk for holding a load of logs. Forwarders frequently travel on the debris (slash) from limbs and tops to avoid rutting the soil.

Landing Operations

At the landing, material may be delimbed, topped, bucked or slashed into product lengths; debarked, chipped or ground and blown into a van; or loaded directly onto a trailer before being transported over haul roads to a mill or other site. Landing equipment may include a chainsaw, slasher, chipper, or tub grinder (Figure 9-2).

If bucking, debarking, or other processing occurs on the landing, some limbs, bark, or other woody debris could become piled. That residual wood could be returned to the forest and dispersed by a skidder to redistribute nutrients back to across the site. It also could be converted to chips by a chipper or tub grinder, cut for firewood, burned, or left to decay.

Because of the variety of operations that may occur at a landing, it may be as small as the area adjacent to the haul road or a quarter acre in size or larger. Make it large enough to allow the equipment to operate efficiently, to store products that have not been hauled to the market, for trucks to enter and leave, and for safety. Your forester can help determine the most appropriate size for your landing or landings.

Equipment Selection

Your forester should recommend harvesting equipment that is most appropriate to your management goals. Some of the most important considerations for choosing timber harvesting equipment are described in the following list.

- Tree size affects the size of equipment needed to handle the timber.

- Silvicultural prescriptions (such as clearcutting, shelterwood harvesting, and thinning) influence the choice of felling and skidding equipment as well as where limbs and tops are removed.

- Topography, especially ground slope, affects the type of equipment and method used to skid logs.

- Wood volume to be removed and time constraints influence the preferred mix of equipment.

- Slash cleanup or noncommercial tree removal may require specialized equipment.

- Key site elements, such as unstable soil and proximity to water bodies and wetlands, may limit the size and type of equipment.

Forest Certification

Selling forest products that have been certified is becoming increasingly common. Forest certification is a process that verifies whether your forest management, including timber harvesting, is environmentally appropriate, socially beneficial, and economically viable. This process assures consumers that the forest products they are buying were obtained from well-managed forests. The primary certification systems in the United States are those offered by the Forest Stewardship Council, the Sustainable Forestry Initiative, and the American Tree Farm System.

To qualify for forest certification, you typically must:

- Practice sustainable forestry.

- Abide by forestry-related laws.

- Follow best management practices.

- Conserve biodiversity.

- Protect water quality and other important resources.

The process of certifying your woodland requires an independent evaluator (a professional forester) who has no personal stake in your property to review your management plan and inspect your woodland. You pay a fee for this service. If you do not meet all of the certification criteria, you can make changes in your planning, record keeping, and management activities to comply. In some states an association of loggers has trained and certified loggers to harvest timber in a sustainable manner. Under some certification systems, if such a logger harvests timber from your land in compliance with certification standards, the wood harvested from your land will enter the marketplace as certified wood. This is a low-cost means to sell certified timber without the expense of arranging a professional review of your comprehensive plan and inspection of your woodland.

Many public and forest industry lands in the Lake States are certified. Relatively few family forests are certified because of the inspection and compliance costs. These costs can be reduced if you join other landowners in a cooperative to share in the certification process. Since some paper mills, sawmills, and large retail lumber distributors have made commitments to purchase and sell mainly certified wood products, there may be opportunities in the future to earn more for your certified timber and, therefore, justify the cost of certification. For timber to enter retail markets as fully certified, all handlers must follow a chain-of-custody process to track the wood from the stump to the retail market.

Certification is a voluntary process for landowners, but demand is growing for certified wood so certifying your woodland or timber harvest may give you a marketing advantage. Contact a forester for more information about certification opportunities in your state.