15: Financial Considerations

15. Financial Considerations

Melvin J. Baughman, Extension Forester, Retired, University of Minnesota

Karen Potter-Witter, Professor and Extension Specialist, Michigan State University

Charles R. Blinn, Extension Specialist, University of Minnesota

Michael R. Reichenbach, Extension Educator, University of Minnesota

Reviewed and revised in 2019 by Michael Reichenbach

In this chapter we summarize how your ownership purpose affects the treatment of income for Federal income tax purposes, provide tools for financial analysis, give an overview of estate planning options, and present information on conservation easements. The authors of this chapter are natural resource professionals and are providing interpretation and synthesis of the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) tax codes, personal communication with Certified Public Accountants and review of literature, some of which is published by the USDA Forest Service and others through National Timber Tax website and Forest Taxation website.

Federal tax regulations change frequently. Consult the IRS or your tax advisor for information on specific situations or to learn about recent changes in tax regulations.

Federal Income Taxes and Ownership Purpose

If your woodland is managed to increase the volume and value of the timber on it, Federal income tax codes provide an incentive for operating as a business. To do so requires the landowner to be able to show a business intent or purpose.

Even though income from a timber harvest is infrequent or does not occur during your lifetime, you may operate as a business. You as the landowner must be able to prove that the purpose of your business is to make a profit. Before describing how you might provide evidence of being in business to make a profit, we will describe business, investment, and personal use and their respective relationship to tax treatment of timber sales.

- Business. If you are taking regular and frequent actions to increase the volume and value of the timber on your property then it may be worth your time to operate as a business.

- Investment. If you are holding the land for resale or are not taking regular and frequent actions to increase the volume or value of your timber you may be operating an investment business.

- Personal or hobby use. If you own the woodland as a part of a residence or hunting property, and are not managing the timber you may be caring for your woodland as a hobby use.

Each of these categories have different implications for tax treatment of income and deductions.

The IRS places the burden of proof of your intent on you, the taxpayer. If you do not have frequent income from your property, in other words, you have a timber sale only once or twice in a lifetime, the default is to treat that income as a hobby or personal use. You may, however, treat this income as business income if you have records that show proof of your intentions to operate as a business. The IRS examines the facts and circumstances that indicate the taxpayer has entered into the activity with the motive of making a profit.

In determining whether an activity is engaged in for profit, all facts and circumstances with respect to the activity are to be taken into account. No one factor is determinative. Internal Revenue Code 183 page 4 states:

Whether or not an activity is presumed to be operated for profit requires an analysis of the facts and circumstances of each case. Deciding whether a taxpayer operates an activity with an actual and honest profit motive typically involves applying the nine non-exclusive factors contained in Treas. Reg. § 1.183-2(b). Those factors are:

- the manner in which the taxpayer carried on the activity,

- the expertise of the taxpayer or his or her advisers,

- the time and effort expended by the taxpayer in carrying on the activity,

- the expectation that the assets used in the activity may appreciate in value,

- the success of the taxpayer in carrying on other similar or dissimilar activities,

- the taxpayer’s history of income or loss with respect to the activity,

- the amount of occasional profits, if any, which are earned,

- the financial status of the taxpayer, and

- elements of personal pleasure or recreation.

No single factor controls, other factors may be considered, and the mere fact that the number of factors indicating the lack of a profit objective exceeds the number indicating the presence of a profit objective (or vice versa) is not conclusive. For example, if five factors say the activity is not for profit, but four are on the profit side, the activity still could be determined to be engaged in for profit. More weight is given by the courts to objective facts than to the taxpayer’s statement of his or her intent. Additional explanation on this topic is provided by the IRS.

The following steps may help substantiate the facts and circumstances supporting a claim that you are managing your woodland as a business:

- Get a written woodland management plan that includes:

- A goal to make a profit from forest products.

- Information necessary to make business decisions on each management unit, such as timber volume, value, management actions planned, and a timeline.

- Maintain a timber account showing your basis or original value of all timber and additions or subtractions from that basis.

- Keep a record of forest management activities and their associated costs or income. An example woodland owner record keeping example can be found in Appendix D. Entries may include:

- Forest related work completed or proposed

- Why did or will you conduct the work

- Relation of the work to increased productivity, production of timber, or resource protection

- Date of activity

- Hours you, or your family spent on the activity

- Hours others spent on the activity

- Miles traveled (e.g., list vehicle’s odometer starting and finishing miles)

- Revenue generated

- Expenses incurred

- Acres affected

- Other comments

- Produce a financial analysis for significant management actions.

- Write a Will legally setting up the transfer of your woodland business to heirs

- Keep records of your training and experience in managing your woodland. This includes all extension forestry classes, credit classes and other training offered through any source.

However, it is not any one of these actions that will show you are in business to make a profit, rather it is your ability to show that all of your actions collectively are directly related to generating a profit and profit is a likely outcome of your efforts.

There are tax advantages to operating your woodland as a business including:

- An active business may deduct expenses from any source of income.

- Timber sale income is treated as a capital gain which carries a lower tax rate than ordinary income.

- There is no self-employment tax on capital gains.

- You face no reduction of social security benefits when generating timber sale income since capital gains are not considered earned income.

If you are operating as a business, there is a distinction between an active and passive business. If you are an active participant in a business you must materially participate on a regular, continuous and substantial basis.

Deductions

As a general rule you may deduct expenses from taxable income that are ordinary and necessary to make a profit. How and when deductions may be taken depends on the purpose of your woodland ownership and the type of expense: capital expense, operating expense or carrying charge, and sale-related expense.

Personal Use or Hobby

Operating expenses for timber being grown for a hobby may be deducted only from hobby income in years when income is earned. Expenses that exceed hobby income in a year are permanently lost; they may not be capitalized. Report hobby expenses as “miscellaneous itemized deductions” and deduct them only to the extent they exceed two percent of adjusted gross income.

Investment

Corporate taxpayers may deduct operating expenses from any source of income. However, noncorporate taxpayers report operating expenses as “miscellaneous itemized deductions” and may deduct them only to the extent they exceed two percent of adjusted gross income. As an alternative, you may capitalize operating expenses.

Both corporate and noncorporate taxpayers may fully deduct property and other deductible taxes from any source of income or they may be capitalize and deduct taxes from timber sale income.

Corporate taxpayers may deduct investment interest expense from any source of income. However, noncorporate taxpayers may deduct investment interest expense only up to the total net investment income from all investments. As an alternative, you may elect to capitalize all or part of the interest paid instead of currently deducting it.

Business

The extent to which you may deduct operating expenses, taxes, and interest depends on whether you materially participate in managing the business. To materially participate, you must be engaged on a regular, continuous, and substantial basis.

If you materially participate in managing a business, you may fully deduct all operating expenses, taxes, and interest from income from any source each year as incurred. If business deductions exceed gross income from all sources for the tax year, the excess net operating loss generally may be carried back to the two preceding tax years and, if necessary, carried forward to the next succeeding 20 tax years. You may instead elect to capitalize these timber-related expenses and recover them when the timber is sold.

If you do not materially participate in managing a business, you are considered to be a passive participant. C corporations (subject to corporate income tax) that are not classified as closely held or as personal service corporations may deduct operating costs and carrying charges from a passive timber business from income from any source without limitation. Closely held C corporations (other than personal service corporations) may deduct costs associated with a passive timber business from income from active businesses (but not against portfolio income). Other types of passive businesses may currently deduct operating expenses, taxes, and interest only to the extent of their income from all passive activities during the tax year. Expenses that cannot be deducted during the year incurred may be carried forward to years in which you either realize passive income or else dispose of the entire property that gave rise to the passive loss. You may instead elect to capitalize expenses and deduct them from income when the property is sold.

Financial Analysis of Woodland Investments

Whether its stocks, bonds, mutual funds, or savings accounts, as an investor you are interested in getting the greatest return on each dollar invested. Forest land is no exception. Many landowners, however, overlook the potential opportunity to increase the return on their forest land investment. In addition to providing important wildlife, recreation, and aesthetic values, investing in forest management can add to your financial bottom line. Because management is a long-term proposition, the investments you make need to be carefully considered. When properly applied, modest investments in management early in the life of a forest stand can have a substantial impact on financial returns through increased forest growth, improved wood quality, and greater economic yields in the future. In addition, investing in forest management often compliments many other reasons individuals own forests such as improving wildlife habitat.

Forestry investments generally require a long-range commitment of money, land, time, and other resources. Because such resources are limited, you should identify and evaluate various investment alternatives to determine how these resources can best be used to meet your demands. This process, called financial analysis, is described here. Keep in mind, however, that a financial analysis offers one input toward deciding which alternative is best. Your decisions also may depend on other factors that are not easily quantified or profit-motivated.

There are a number of factors to consider when investing in forest management. These include:

Tolerance for Risk

Future rates of return can’t be predicted with certainty. Investments that pay higher rates of return are generally subject to higher risk and volatility. The actual rate of return on investments can vary widely over time, especially for long-term investments such as forest management, as there is often a large degree of uncertainty that anticipated returns will be fully realized.

This includes uncertainty about future prices for your products (“What markets will exist when my products are ready for sale?”), management costs (“What will be my annual tax liability for the property?”), and future forest conditions (“Will forest growth increase in response to management as expected?” “Will the forest be affected by insect or disease infestation or wildfire?”).

Investment Timelines

Landowners need to consider the timeframe associated with their forest management investments. The income or benefits from these investments may not be realized for years or even decades. In some cases, it may be your heirs that realize the investments you make today in your forests.

Portfolio Diversification

For many individuals, investing in forest management provides added diversification that complements an existing investment portfolio.

Stand Suitability for Potential Practices

The existing condition of your forest (such as tree types, sizes, ages) will often dictate the opportunities to invest in forest management, as well as the specific practices that can be applied.

Financing

Depending on your access to capital to fund investments in forest management, you may need to secure outside funding. The terms of outside financing (that is, the interest rate charged by the lending institution, repayment period, the amount of financing obtained) can vary considerably and have a substantial impact on the financial feasibility of an investment.

When to Sell your Products

How will you know when your timber and other forest products are ready for harvest? What criteria will you use to make this determination? From a strictly financial perspective, you will want to sell your products when they no longer increase in value at a rate that exceeds your next best investment opportunity (such as your opportunity cost). For example, if you could invest the proceeds from the sale of your forest products into an account earning an eight percent annual return, you would want to let your forest grow until its value increases at a rate that is less than eight percent per year. The timing of any income-generating activities can also be affected by other factors such as the immediate need for money, anticipation of an insect attack, or cleanup following a windstorm.

Marketing

When your forest products are ready for sale, there will likely be costs associated with preparing your stand for sale and finding a market for the products. Many landowners use a consulting forester to oversee the sale of forest products. They will typically collect a fee that represents a percent of the gross sale value.

Importance of Benefits which are Difficult to Quantify

Forest management may involve selling timber or other forest products to markets which pay for delivered material. It can also provide other benefits that may not have a well-defined market (such as aesthetics, bird-watching). As the significance of these non-market benefits varies from one landowner to another, it may be important to weigh them in any management decisions.

Taxes

Property taxes are usually the single largest recurring annual cost of forest management. What are the expectations about the future level of property taxes? Additionally, how will federal and state income tax provisions (such as treatment of timber income and management expenses) affect the performance of my investment?

Record Keeping

Important, but often overlooked is keeping complete and detailed records of your forest management activities. These records are not only important for tax purposes, but they also enable you to better document the timing and types of treatments applied to your stand.

Government and other Support or Incentive Programs

There are several government-sponsored programs that provide technical and/or financial assistance to landowners interested in managing their forest. This includes cost-share funds to help with certain management practices such as tree planting or other silvicultural activities. A consulting forester or your local department of natural resources office can help you identify the programs applicable for your situation.

Steps in a Financial Analysis

Investments require costs and produce benefits or income at various points over time. The timing and amounts of these cash flows determine the profitability of an investment alternative.

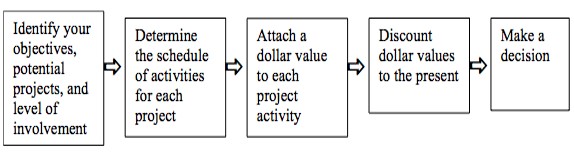

A financial analysis requires identifying objectives, potential projects and your level of involvement; determining the schedule of activities for each objective; attaching a dollar value to each activity; and discounting those dollar values to the present (Figure 15-1). Your consulting forester can help you with many parts of this process.

1.Identify your Objectives, Potential Projects, and Level of Involvement

Sound planning begins with determining your objectives, identifying potential projects which might help you achieve those objectives, and deciding the level of involvement you want to have with on-the-ground management of your forest. When identifying your objectives, it may be useful to write a short description of the situation or to describe the desired outcome in a clear, concise statement. Develop a list of potential solutions or investment alternatives which might help achieve your objectives. To reduce the number of alternatives to a manageable few, start by considering your resources such as:

- Technical-equipment, species, etc.

- Economic-relationship between benefits and costs (timing, amount, etc.).

- Commercial-availability of markets.

- Financial-amount of available funds and other financial obligations.

- Personnel-adequacy of staffing (number, capabilities, etc.).

- Legal/Ethical-relationship with accepted standards and expectations.

You probably lack data to predict outcomes for many alternatives. Many otherwise promising options may be discarded because there is little or no information regarding benefits.

While being actively involved in on-the-ground management activities can save you money, it takes time. Do you anticipate doing those activities as a hobby when time permits or do you plan to make it a major line of your work? Because the amount of involvement often depends on the perceived returns, leave room for flexibility. You can rerun your analysis to evaluate how different levels of personal involvement or hired services will impact your profitability.

2. Determine the Schedule of Activities for Each project

Each project that you might undertake has an associated schedule of activities during its life. The events should be placed in the appropriate year(s) on a time line to help you track these activities over time. A sample time line for a Christmas tree farm is shown in Table 15-1.

| Years in the future | Activity |

|---|---|

| 0 | Site preparation, tree planting, weed control, spraying, taxes |

| 1 | Spraying, fertilize, weed control, taxes |

| 2 | Spraying, fertilize, shearing, taxes |

| 3 | Spraying, shearing, taxes |

| 4 | Spraying, shearing, taxes |

| 5 | Spraying, fertilize, shearing, taxes |

| 6 | Spraying, shearing, tree sales, taxes |

| 7 | Spraying, shearing, tree sales, taxes |

In this case, site preparation, planting, weed control, spraying, fertilizing, shearing, payment of property taxes, site cleaning, and marketing are needed during various years. While site preparation and tree planting would occur now according to the timeline (Figure 15-2), the marketing of trees (sale) would occur six and seven years in the future. Make sure your timeline include all activities, including your own investment of time that the project will require.

3. Attach Dollar Values to Each Project Activity

Identify those activities from your time line that involve a cash transaction where you are either receiving income (a benefit) or paying someone (a cost). For each of those activities, determine the associated dollar value. Do not include the cash flow from an existing or completed project as an initial benefit in an analysis. However, that income may be used as available funds to cover investment costs.

As the economic environment is constantly changing and your financial analysis is heavily influenced by your assumptions about the timing and dollar amount of financial transactions, it is very important to have the best and most current information available. Some products have grower associations such as a Christmas tree grower’s association or a maple syrup producers association. These associations may be of some assistance in determining dollar values, growth rates, insurance costs, etc. Some products however do not yet have well-defined markets and prices. In these cases, foresters and extension educators may be of some assistance. When defining dollar values, make sure that they are all expressed in the same units (such as $/acre, $/year).

4. Discount Values to the Present

If you deposit funds into a saving account, you expect your investment to grow over time through a process called compounding. Compounding occurs when interest is paid on the original principal and on the accumulated past interest. Assuming a 5 percent interest rate and compounding once a year, a $100 investment would grow to $105 ($100 X 1.05) at the end of the first year and $110.25 ($105 X 1.05) at the end of the second year. Before you can compare your alternatives and make a decision (Step 5), you must convert the cash flows on your time line into comparable values. This is done through a process called discounting, which is just the opposite of compounding; it starts with a future value and finds its worth today. The formula for calculating the present value of a future value is:

PV = FV / (1+i)n

Where:

PV = Present value

FV = Future value

i = Alternative rate of return or interest rate (expressed in decimal form)

n = Number of years in the future when the transaction occurs.

Fortunately, computer spreadsheet programs contain built-in functions for determining the present value of future financial transactions. The key factor when discounting values to the present is determining the discount rate or alternative rate of return (i). This is the cost of borrowing money or the best rate of return available in other investments. These other investments may be alternative land uses, what you can earn through financial markets, or the rate of return available in a savings account or money market fund.

Using the formula above, the present value of $110.25 in two years is $100 using a discount rate of 5 percent:

$100 = $110.25 / (1+0.05)2

Or, suppose that a future transaction will provide $250 in 10 years. If your savings account pays 7 percent interest, then FV = $250, i =0.07 (for 7 percent), and n = 10. The calculated present value is $127.09. You would do the same for all financial transactions which occur in the future, discounting them to the present.

Depending on an individual’s financial resources, tolerance for risk, and investment preferences (such as stock market vs. savings account) the discount rate applied may vary from one individual to another. As a result, the present value for a future transaction can vary considerably among individuals. For example, the present value of the same $250 transaction in 10 years is $139.60 using a 6 percent interest rate.

5. Make a Decision

There are many economic decision rules that can analyze the financial feasibility of investment opportunities. One of the more common is net present value (NPV), the difference between a project’s discounted benefits and discounted costs. A positive NPV indicates that a project is a better use of your resources when compared to the rate of return you could get from your next best investment opportunity (i.e., your discount rate).

The investment alternative with the highest positive NPV is generally the preferred alternative. You need to consider additional factors such as the amount of risk, investment timelines, the amount of uncertainty associated with future cash flows, tax implications, non-market benefits provided or affected (such as aesthetics, bird-watching), your labor, etc. before making a final decision.

As an example, suppose you identified the two investment options shown below with an alternative rate of return of 7 percent. Neither option provides net income until the third year. The NPV for Option A is $16.61 and $17.62 for Option B. Because both options have a positive NPV, we know that they will each return more than the alternative rate of return (7 percent). Based solely on financial criteria, Option B would be preferred because it has the largest NPV. But, because a financial analysis only incorporates project costs and benefits that can be quantified, consideration of other factors may result in Option A being preferred:

Example

The farm you grew up on is now being sold by your parents who are retiring. Your siblings and you decide to purchase the farm to keep it in the family. While your brothers and sisters decide to keep their part of the farm in production, you are going to establish pheasant habitat on the 100 acres you purchased, with the intent of leasing the hunting rights once the habitat is suitable. Your estimated costs and returns are as follows:

- $750/acre purchase price of land, paid back annually in equal installments over 5 years at 9% annual interest.

- $200/acre wildlife habitat establishment costs incurred one year after purchase.

- $50/acre habitat maintenance costs in years 2-3.

- $10/acre habitat maintenance costs in years 4-10.

- Annual recreation leases of $140/acre beginning in years 4-9.

- $5/acre/year in property taxes and liability insurance, beginning immediately.

- You plan to sell the land in year 10 for $1,300 per acre.

- Your alternative rate of return is 7%.

Adding numbers in the Net Return row of the Discounted Cash Flow table above, we find, the net present value is $59/acre (rounded to the nearest dollar). Because that value is positive, this alternative will provide a 7 percent rate of return plus an additional $59 acre. Assuming that the level of risk, investment timelines, the amount of uncertainty associated with future cash flows, tax implications, non-market benefits provided or affected (such as aesthetics, bird-watching), your labor requirements, etc. are acceptable, you would prefer this alternative to the one which yields a 7 percent rate of return.

Planning for your Woodland Legacy

What will happen to your woodland after you are gone? Most landowners would like to see their woodland pass on to the next generation without being subdivided or at least be sold to someone who cares as much as you do about keeping the woodland wooded.

After managing a woodland for many years, you want to preserve its financial and other values for the benefit of future generations. Discuss your goals for the property with family members and others that have a stake in it. Developing a common understanding about the future of the woodland is essential to sucessful transition of woodland ownership. Use the goals worksheets in the online resources to develop a list of goals for you and your family and then work through goal sheet develop a prioritized common list of goals. Then fine-tune your goals and work with professional advisors (attorney, accountant, and forester) to find the right mechanism for passing on your legacy.

Wills and Trusts

Prepare a will to insure that taxes and creditors are paid and assets are transferred to heirs as you wish. A will does not control distribution of some assets, such as property held in joint tenancy, life insurance, and retirement plans. Designate beneficiaries on financial accounts (such as retirement accounts, bank accounts, life insurance) to keep them out of probate.

A trust can be written to specify how assets will be managed and distributed after death. Assets can be transferred to the trust during the lifetime of the trustor or at death. The trustee is obligated to manage the trust’s assets for the benefit of beneficiaries. The trustee must file income tax returns and pay taxes on income retained in the trust while beneficiaries pay income taxes on funds distributed to them.

A revocable living trust enables the creator to become both the trustee and beneficiary. This trust may be amended or revoked at any time. The trust is not subject to income tax. By designating an alternate trustee, it provides financial protection in case of disability and assets transferred to the trust during the trustor’s lifetime avoid probate at death. Estate taxes cannot be avoided by this trust.

Types of Business Ownership

Different forms of business ownership can be used to pass on your management goals to the next generation. The following describes some of these.

Sole Proprietorship

This business has one owner. Startup costs are low, income and taxes are reported on the owner’s tax return, one person makes all decisions, and no documents are required to describe the business or its management. The owner is not protected from liability and the business ends when the owner dies. Upon death of the owner, the business’s value is its fair market value at the date of death.

Joint Tenancy and Tenants-in-Common

More than one individual owns the business. The business pays no tax, but does file a tax return to report income or loss. Partners report their share of the income on individual tax returns. Partners are not employees so no payroll tax is reported. Partners can pool finances and share management with few legal restrictions. Every partner shares liability for his or her own actions, for actions of other partners, and for actions of employees. The joint ownership terminates at the death or bankruptcy of any partner. Written buy-sell agreements are important to determine what happens to the business and land when an owner dies. Individual owners in the land can demand their share of the fair value of the property at any time, and force the sale of the property to get their value out. This creates an unpredictable situation for remaining owners. When the death of a partner occurs,

- Under joint tenancy, ownership passes automatically to the remaining partners.

- Under tenants-in-common, ownership passes to the heirs of the partner that died if there is no buy-sell agreement between partners.

Limited Liability Company

This entity combines features of a partnership and corporation. Owners are called members. The business pays no tax, but does file a tax return to report income or loss. Members report their share of the income on individual tax returns. Members are not employees so no payroll tax is reported. One or more general members manage the business for the benefit of all members. This arrangement, like the family limited partnership allows selected family members that are most interested and competent to manage the business to the benefit of all while allowing other family members to transition into management over time. Members have limited liability for business actions and debts. Profit distribution is flexible. LLCs can be created with unlimited life. At the death of a member, buy-sell agreements control how member interests are valued and transferred. Valuation is based on the business’s assets and cash flow, reduced by any restrictions in the membership agreement. Each state has different laws and regulations concerning LLCs. This is a popular business entity for ownership and transfer of land between generations.

Land Protection Options

Many woodland owners invest a great deal of time and money into managing their woodland and wish to preserve the features they value about their land for future generations. However,pressure to develop that woodland for residential or business use may lead a future landowner to sell the property for such development. Woodland can be protected from development by a conservation easement.

Conservation Easement

A conservation easement is a legally enforceable land preservation agreement between a landowner and a land protection organization, such as a nonprofit land trust or public agency. The owner typically gives up the right to develop the land while retaining other rights, such as the right to sell the property, live on the property, manage timber, recreate, and mine subsurface minerals. All rights are negotiable between the landowner and the entity holding the easement. The receiving organization is obligated to prevent future development of the property and may have other rights to use it for conservation purposes stipulated in the agreement.

There are several benefits of a conservation easement to the landowner, foremost of which is that the land will continue to be managed and used as the current owner specifies. If the fair market value of the land declines as a consequence of the easement, the landowner may deduct this “loss” as a charitable contribution on federal income taxes [Internal Revenue Code Section 170(h)]. Lowering the property value also lowers the estate value, thus reducing estate taxes when the property owner dies. A conservation easement does not always result in a lower property value since the property’s value as “green space” in a rapidly developing area may sustain or raise the property value.

Conclusion

In this chapter we provide an introduction to how ownership purpose or intent to make a profit determines how income and deductions are treated for income tax purposes. We hope the information will help you make decisions about whether to operate as a hobby, investment or business. While there are significant tax advantages to operating as a business, it also requires investment of time and effort on your part to keep records, determine the original cost basis for your land, timber and other assets and to project into the future the return on your expenditures. We also introduced planning for your woodland legacy, an on-going process that involves family communication, the development of legal documents and use of business structures to pass land to the next generation or to new owners.