15.8 Wording of Survey Questions

The wording of questions is a major area of concern in constructing a questionnaire or evaluating someone else’s survey. Question bias, clarity, length and construction can cause crucial differences in results from surveys. Closed-ended questions are the norm for most survey questionnaires.

-

Questions should be clear, using everyday language and avoiding jargon.

-

Questions should be short, thereby reducing the likelihood of being misunderstood, especially in telephone interviews.

-

Questions should not ask more than one thing. An example of a double-barreled question might be: “This product is mild and gets out stubborn stains. Do you agree or disagree?” The respondent might agree with the first part of the statement, but disagree with the second.

-

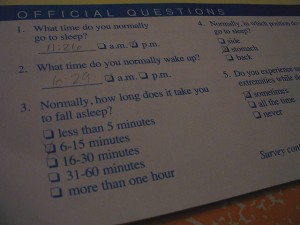

piratejohnny – Sleep survey – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Questions should avoid biased words or terms. An example might be: “Where did you hear the news about the president’s new tax program?” The word “hear” biases against an answer such as “I read about it online.” Instead ask, “Where did you learn the news….” There are even more insidious examples of bias in questions, a result of the survey sponsor’s having an interest in seeing the survey produce a certain set of answers. Think about the difference between asking about “pro-choice” or “pro-life” opinions. Questions can be written to signal the respondent about exactly what the interviewer wishes to get as the “right” answer.

-

Questions should avoid leading the respondents’ answers. For example, asking the question “Like most Americans, do you support the government’s war on terror?” leads the respondent to think that if he or she answers “no,” they are in an un-American group! Another example might be: “Do you believe, along with many others of good faith, that abortion is murder?” The leading question tells the respondent what the expected answer is.

-

Questions should avoid asking for unusually detailed or difficult information. A detailed question might be: “Over the past 30 days, how many hours have you spent watching TV?” Most respondents would not be able to answer that question without considerable calculation. A simpler way of gathering the same information would be to ask, “About how many hours a day do you spend watching TV?”

-

Questions should avoid embarrassing the respondent whenever possible. It is difficult to judge which kinds of questions will be embarrassing to every person, but some questions will embarrass almost everyone. For instance, questions about level of income are usually perceived as intrusive. In fact, many survey researchers put those questions at the very end of the questionnaire so that if the respondent is offended by the question, the rest of the interview is not spoiled.

-

Questions should not assume knowledge on the part of the respondent. Many surveys include “filter questions” which help the interviewer decide whether that part of the questionnaire is pertinent to the respondent. For instance, the questionnaire might ask: “Have you purchased something online in the past month?” If the respondent says “no,” then the questions that deal with the online purchase experience are best not answered by that respondent.

-

Questions should avoid abbreviations, acronyms, foreign phrases or slang. Respondents are less likely to be confused when simple, familiar language is used. Also, certain slang phrases may connote some kind of bias on the part of the interviewer, which will influence the respondent.

-

Questions should be specific about the time span that is implied. For instance, a question may ask about the respondent’s approval or disapproval of a $20 billion program for road and bridge improvement. Unless the question specifies the number of years over which the money will be spent, the respondent has no way to evaluate the program’s impact and the answer given will be meaningless.

-

Where appropriate, questions should attempt to gauge the intensity of feeling the respondent has about a topic. For instance, a question may ask for the respondent’s preference for one product over another. Some respondents may not feel particularly intense about their preference for either, but just to be polite, they will give an answer. If an intensity question were included (“How strong is your preference for Product A?”), those who were less intense could indicate their ambivalence.

-

Questions should avoid using a forced response strategy. Respondents should have the option to say “I don’t know” or “I don’t have enough information to answer” to avoid the problem of respondents giving an answer, any answer, just to be polite. (Wimmer & Dominick, 113-120)