13.2 Crimes Involving Terrorism

Learning Objectives

- Identify three federal statutory schemes targeting terroristic conduct.

- Ascertain the function of the Department of Homeland Security.

- Define international and domestic terrorism.

- Identify crimes involving terrorism.

- Identify potential constitutional challenges to the USA PATRIOT Act.

In recent years, crimes involving terrorism have escalated both in the United States and abroad. The federal government’s response has been to enact comprehensive criminal statutes with severe penalties targeting terroristic conduct. In this section, federal statutes criminalizing acts of terrorism are reviewed, along with potential constitutional challenges.

Statutory Schemes Targeting Terrorism

Before the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States, the primary federal statutes criminalizing terrorism were the Omnibus Diplomatic Security and Antiterrorism Act of 1986 and the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA), which was enacted after the Oklahoma City bombings. After September 11, 2001, Congress enacted the USA PATRIOT Act, which stands for Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001.

The USA PATRIOT Act changed and strengthened existing laws targeting terrorism and enhanced US capabilities to prosecute terrorism committed abroad. Specifically, the USA PATRIOT Act increases federal jurisdiction over crimes committed outside the United States (USA PATRIOT Act, Tit. VIII § 804, 2011), creates new crimes involving financial support of terrorism or terrorists abroad (USA PATRIOT Act, Tit. VIII § 805, 2011), and provides for the civil forfeiture of assets connected to terrorism (USA PATRIOT Act, Tit. VIII § 806, 2011). Other fundamental changes incorporated in the USA PATRIOT Act are the expansion of government surveillance capabilities, including telephone interception and scrutiny of e-mails (USA PATRIOT Act, Tit. II, § 203 et seq.).

In 2002, Congress created the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) under the authority of the Homeland Security Act. DHS enforces provisions of federal laws against terrorism and includes the following agencies: the Secret Service, Customs, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, United States Coast Guard, Border Patrol, Transportation Security Administration, and Citizenship and Immigration Services (Department of Homeland Security website, 2011).

Criminal Terroristic Conduct

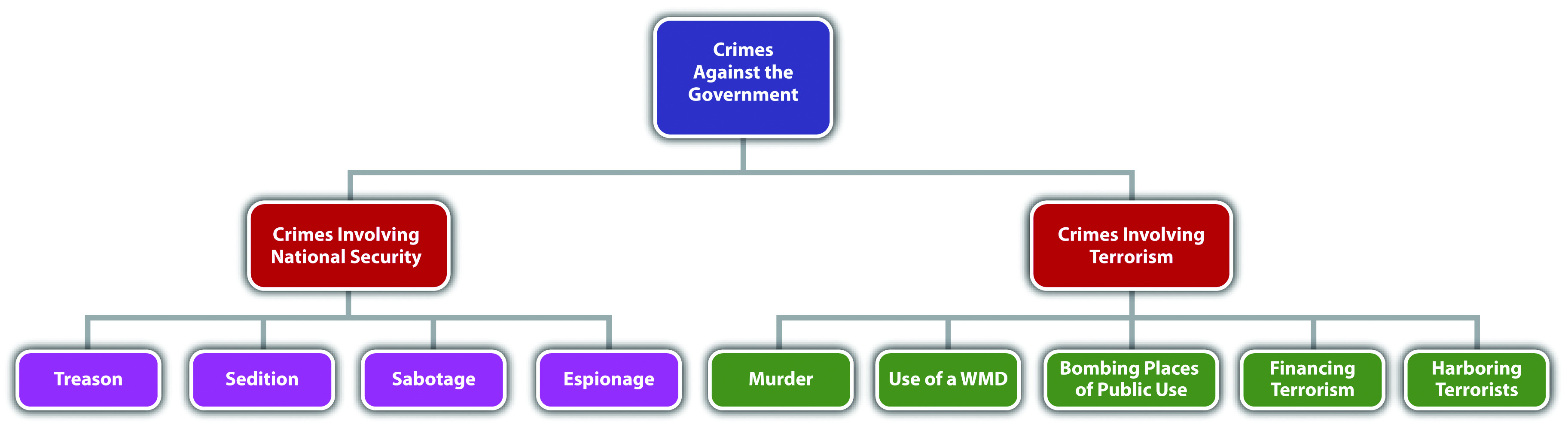

International terrorism is defined as violent acts committed outside the United States that would be criminal if committed in the United States, and that appear to be intended to influence a civilian population or government by intimidation, or to affect the conduct of government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping (18 U.S.C. § 2331(1), 2011). Specific crimes such as murder, attempted murder, and conspiracy to commit murder committed against an American national (defined as an American citizen or individual who owes permanent allegiance to the United States)(18 U.S.C. § 1101(a), 2011) while outside the United States are graded as high-level felonies with all ranges of sentencing options available, including the death penalty (18 U.S.C. § 2332, 2011).Domestic terrorism is defined exactly the same as international terrorism, except that the violent acts are committed within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States (18 U.S.C. § 2331(5), 2011). Prohibited as terrorism are the use of a weapon of mass destruction, which is defined as any destructive device or weapon designed to cause death or serious bodily injury through the release of chemicals, toxins, or radioactivity (18 U.S.C. § 2332A(c), 2011), bombings of places of public use—including public transportation systems (18 U.S.C. § 2332F, 2011)—financing of terrorism (18 U.S.C. § 2339C, 2011), harboring or concealing terrorists (18 U.S.C. § 2339, 2011), or attempt or conspiracy to do any of the foregoing. All these crimes are graded as serious felonies.

Example of Terrorism

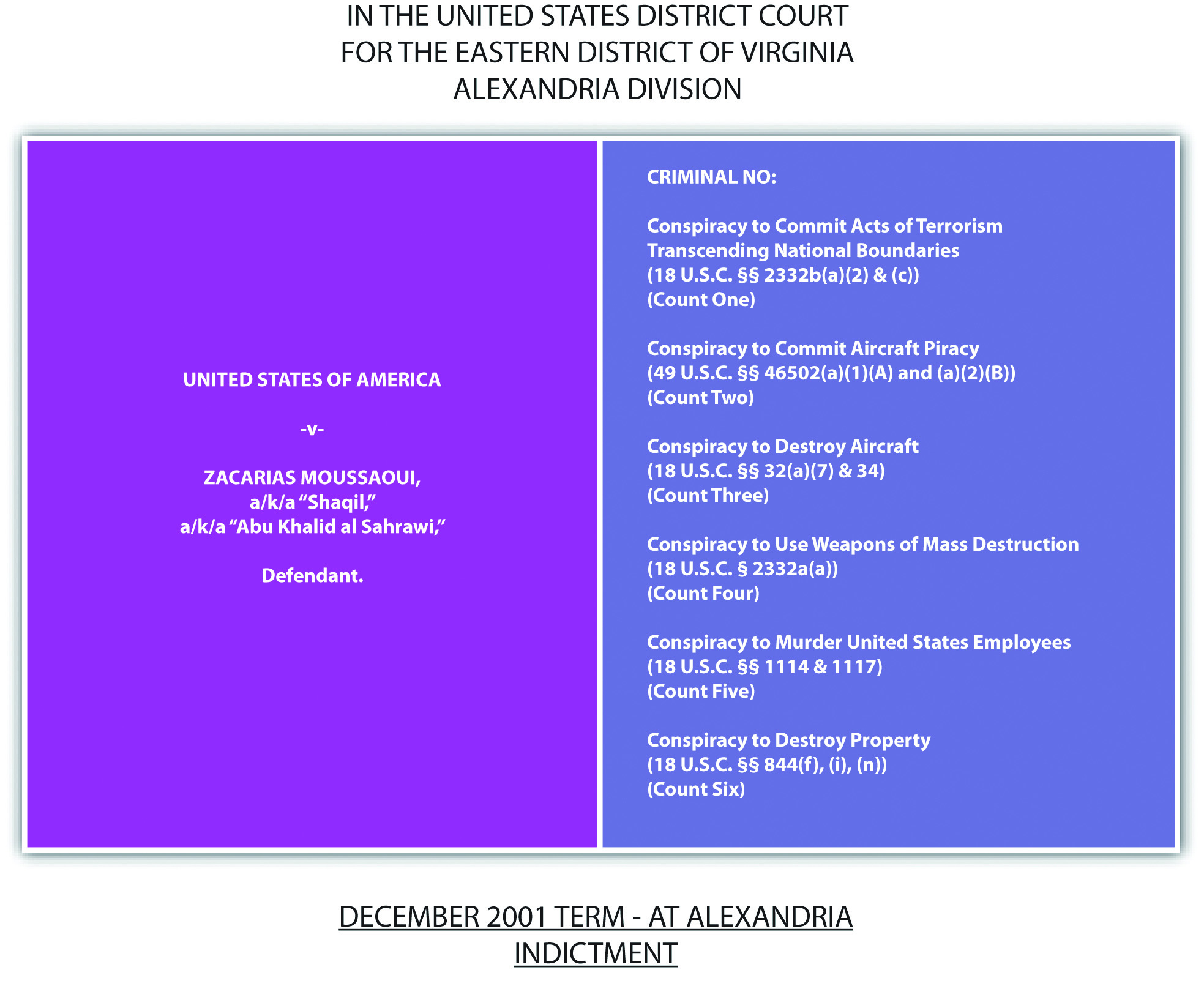

Zacarias Moussaoui, a French citizen, was the only defendant prosecuted for the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Although Moussaoui was not onboard any of the planes that crashed into the World Trade Center, Pentagon, and a Pennsylvania field because he was in federal custody, he was indicted (Zacarias Moussaoui indictment, 2011) for several counts of conspiracy to commit terrorism and aircraft piracy and pleaded guilty to all charges. Specifically, Moussaoui pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit acts of terrorism transcending national boundaries, conspiracy to commit aircraft piracy, conspiracy to destroy aircraft, conspiracy to use weapons of mass destruction, conspiracy to murder US employees, and conspiracy to destroy property of the United States. After the extended trial, during which Moussaoui attempted to represent himself, and the resulting guilty pleas, the jury carefully considered and recommended against the death penalty for Moussaoui, who was thereafter sentenced to life in prison (Markon, J. & Dwyer, T., 2011). Moussaoui later moved to withdraw his guilty pleas, but his motion was rejected by the US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia (U.S. v. Moussaoui, 2011), whose decision was later affirmed by the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit (U.S. v. Moussaoui, 2011).

Constitutional Challenges to the USA PATRIOT Act

Portions of the USA PATRIOT Act provide for enhanced government surveillance capabilities, which are considered a search, so constitutional implications are present pursuant to the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits unreasonable search and seizure. In addition, provisions of the Act that prohibit financing terrorists and terrorism have been attacked as violative of the First Amendment’s protection of free speech, free association, and freedom of religion. Litigation involving these challenges is ongoing and was filed on behalf of citizens by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) (Kranich, N., 2011).

Key Takeaways

- Three statutory schemes targeting terroristic conduct are the Omnibus Diplomatic Security and Antiterrorism Act of 1986, the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, and the USA PATRIOT Act.

- The Department of Homeland Security enforces terrorism laws.

- The definition of international terrorism is violent acts committed outside the United States that would be criminal if committed in the United States and that appear to be intended to influence a civilian population or government by intimidation, or to affect the conduct of government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping. The definition of domestic terrorism is exactly the same, except the criminal acts take place within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States.

- Examples of crimes involving terroristic conduct are murder, use of a weapon of mass destruction, bombing places of public use, financing terrorism, harboring a terrorist, and conspiracy or attempt to commit any of the foregoing.

- The USA PATRIOT Act expands government surveillance capabilities, so it is subject to a Fourth Amendment challenge as an unreasonable search, and also prohibits financing terrorism, so it is subject to a First Amendment challenge as a prohibition on free speech, freedom of religion, and freedom to associate.

Exercises

Answer the following questions. Check your answers using the answer key at the end of the chapter.

- Joshua shoots and kills Khalid in front of the Pakistani Embassy in Washington, DC. Is this an act of domestic terrorism? Why or why not?

- Read Humanitarian Law Project v. Reno, 205 F.3d 1130 (2000). Did the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit uphold 18 U.S.C. § 2339, which prohibits providing material support to terrorists? What were the constitutional challenges to this federal statute? The case is available at this link: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=6926778734800618484&q= convicted+%222339%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=2000.

- Read Humanitarian Law Project v. U.S. Department of Justice, 352 F.3d 382 (2003). In this case, the same federal statute was analyzed (18 U.S.C. § 2339) as in Humanitarian Law Project v. Reno, in Exercise 2. Did the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit uphold the statute in the face of a Fifth Amendment challenge that the statute deprived the defendants of due process of law? Why or why not? The case is available at this link: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=2048259608876560530&q= convicted+%222339%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=2000.

References

Department of Homeland Security website, accessed May 4, 2011, http://www.dhs.gov/index.shtm.

Kranich, N., “The Impact of the USA PATRIOT Act: An Update,” Fepproject.org website, accessed May 4, 2011, http://www.fepproject.org/commentaries/patriotactupdate.html.

Markon, J., Timothy Dwyer, “Jurors Reject Death Penalty for Moussaoui,” Washington Post website, accessed May 11, 2011, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/05/03/AR2006050300324.html.

U.S. v. Moussaoui, Criminal No. 01-455-A (2003), accessed May 4, 2011, http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/moussaoui/withdrawguilty.pdf.

USA PATRIOT Act, Tit. II, § 203 et seq., http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=107_cong_public_laws&docid=f:publ056.107.pdf.

USA PATRIOT Act, Tit. VIII § 804, accessed May 4, 2011, http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgibin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=107_cong_public_laws&docid=f:publ056.107.pdf.

USA PATRIOT Act, Tit. VIII § 805, accessed May 4, 2011, http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=107_cong_public_laws&docid=f:publ056.107.pdf.

USA PATRIOT Act, Tit. VIII § 806, accessed May 4, 2011, http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=107_cong_public_laws&docid=f:publ056.107.pdf.

Zacarias Moussaoui indictment, Justice.gov website, accessed May 4, 2011, http://www.justice.gov/ag/moussaouiindictment.htm.

18 U.S.C. § 1101(a) (22), accessed May 3, 2011, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/html/uscode08/usc_sec_08_00001101—-000-.html.

18 U.S.C. § 2331(1), accessed May 3, 2011, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/718/usc_sec_18_00002331—-000-.html.

18 U.S.C. § 2331(5), accessed May 3, 2011, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/718/usc_sec_18_00002331—-000-.html.

18 U.S.C. § 2332, accessed May 3, 2011, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/718/usc_sec_18_00002332—-000-.html.

18 U.S.C. § 2332A(c) (2), accessed May 4, 2011, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/718/usc_sec_18_00002332—a000-.html.

18 U.S.C. § 2332F, accessed May 4, 2011, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/718/usc_sec_18_00002332—f000-.html.

18 U.S.C. § 2339, accessed May 3, 2011, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/718/usc_sec_18_00002339—-000-.html.

18 U.S.C. § 2339C, accessed May 3, 2011, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/718/usc_sec_18_00002339—C000-.html.