2.6 Engaging in Healthy Behavior Change

Considering the numerous barriers to physical activity reviewed above, healthy behavior change and adoption of a habitual physical activity regimen into an individual’s lifestyle may seem like a daunting task. College students may feel particularly challenged in implementing a regular physical activity plan into their schedule, given the need to balance school, work, and social lives. Thus, an individual must weigh his or her current “readiness” to make a behavior change in order to effectively plan and implement desired behavioral changes into their daily routine.

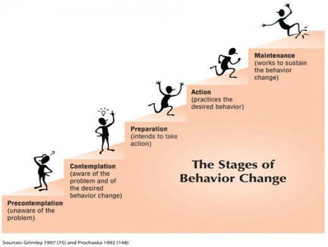

The Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change

The Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Health Behavior Change (TTM) proposes the concept of healthy behavioral change as a series of stages an individual must progress through to achieve success in altering his or her behavioral patterns (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). Numerous studies support using this model for healthy eating and physical activity behavior change endeavors (Marshall & Biddle, 2001). The TTM stages are as follows:

- Precontemplation

- Contemplation

- Preparation

- Action

- Maintenance

The five stages of change correlate to the statements of: “I won’t/I can’t”, “I may”, “I will”, “I am”, and finally, “I still am.” Consider the following example of a college student beginning a new exercise regimen in order to visualize the stages of the TTM.

Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Health Behavior Change (TTM)

- Precontemplation: The student believes that s/he is not capable of jogging a mile continuously; therefore s/he does not engage in any physical activity.

- Contemplation: The student begins to contemplate the target behavior (completing a 1-mile jog), and s/he is now open to the possibility of future success. However, the student has not yet definitively set a date to begin training.

- Preparation: The student has now firmly committed to start training for the target behavior, and has joined a local jogging group in order to stay accountable. At this stage, the student may be participating in short jogging bouts, but has not yet attempted to run continuously for 1 mile.

- Action: The student is now participating in regular training, and has completed several 1-mile jogs. The student feels as if s/he has achieved their behavioral goal.

- Maintenance: The student has continued to train by engaging in multiple distance runs. Perhaps the student has progressed to a fitness level where s/he may target an advanced goal (for example: completing a 5K race), and therefore s/he may cycle through the TTM stages again with this new goal in mind.

Creating Healthy Physical Activity Habits: Increasing Self-Efficacy and Goal-Setting

Strategies which may assist an individual in overcoming physical activity barriers– thus, facilitating successful progression through the TTM stages of change – include increasing self-efficacy for physical activity, and engaging in effective goal-setting.

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s beliefs that s/he will be successful in performing a specific behavior, whereas self-confidence refers to a more global sense of personal worth.Physical Activity Self-Efficacy: Self-efficacy is defined as the belief that one has the ability to initiate or sustain a desired behavior (Bandura, 1994). Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s beliefs that s/he will be successful in performing a specific behavior, whereas self-confidence refers to a more global sense of personal worth. Studies indicate that increased self-efficacy may positively impact an individual’s motivation to participate in a particular behavior, the performance achievements gained from participation in said behavior, and overall well-being (Bandura, 1994). Notably, self-efficacy can be developed for a variety of human behaviors. However, for the purpose of the current Chapter, physical activity self-efficacy will be exclusively reviewed. It is important to note that improvements in physical activity self-efficacy may reduce an individual’s negative perceptions of exercise, a commonly cited barrier to physical activity (CDC, 2016). …improvements in physical activity self-efficacy may reduce an individual’s negative perceptions of exercise…

Factors that may enhance an individual’s self-efficacy for physical activity include:

- Experiencing positive physiological states (i.e., mood)

- Receiving verbal encouragement for physically active behavior

- Observing others successfully performing physically active tasks (i.e., role model)

- Mastering physical activity skills on an individual level (Moore & Tschannen-Moran, 2010).

Comprehension check:

How may you increase your self-efficacy for physical activity? Please provide a detailed answer. (Hint: do you acknowledge positive physiological cues during or after exercise (i.e. calm breathing, relaxed state)? Do you surround yourself with individuals who voice their support for your exercise endeavors?)

Physical activity self-efficacy can be strengthened in three areas which correlate with personal, environmental, and behavioral factors.

- Personal (Mood): Noticing and acknowledging positive physiological states (i.e., feelings of calmness and enjoyment) during physical activity may increase self-efficacy for future physical activity participation.

- Environmental (Surrounding oneself by a healthy environment): Speaking positively about physical activity participation (verbal encouragement) and observing and being mindful of the physical activity behaviors of those individuals in one’s social group (watching role-models in exercise and sport) may positively impact an individual’s self-efficacy for future physical activity participation.

- Behavioral (Engaging in exercise – “doing”!): Engaging in consistent, successful efforts related to physical activity (mastery experiences) may increase physical activity-related self-efficacy.

Goal-Setting for Physical Activity: The first step in creating and maintaining a regimen for lifelong participation in physical activity is to identify desired outcomes. Perhaps the desired outcome is to embrace a healthy lifestyle, enhance mental wellbeing, and improve self-esteem. Research clearly indicates that exercise may produce numerous positive outcomes; however, the challenge lies in overcoming perceptual and environmental barriers in order to consistently follow an exercise plan. Often, an individual will revert to old habits of inactivity (despite his or her desired outcomes) if clear goals are not set regarding physical activity participation.

Participation in habitual physical activity requires a clear vision for oneself, effective goal-setting, and self-monitoring of progress. Participation in habitual physical activity requires a clear vision for oneself, effective goal-setting, and self-monitoring of progress. A review of how to best create a vision, set appropriate goals, plan for adversity, and self-monitor is the final step in this Chapter’s overview of the benefits of physical activity, perceived barriers, and healthy behavior change sections. Research indicates that the following methods may be effective in planning, monitoring, and adhering to a personal health and fitness program (Locke & Latham, 2002).

- Create a compelling vision: Before beginning your behavior change journey, take a moment to create a vision of a “healthier you.” What is driving you to engage in behavior change? Why do you wish to create new health habits? How will this improve your life? How will this positive change benefit those close to you? What behaviors do you wish to consistently engage in to become your “best self?”

- Design behavioral goals for your exercise plan: Create S.M.A.R.T. goals for your health regimen. The most powerful goals are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound. Goals may be short-term, or long-term.

- Plan for setbacks: Mentally acknowledge that you will encounter setbacks on your behavior change journey. Discern how you will best overcome these setbacks, and write down a “game plan” for challenging situations. How will you react and respond to adversity?

- Track and measure progress: Keep a journal of your progress, and self-monitor any adjustments you need to make in order to be successful in maintaining your plan. Once you have achieved several of your short-term goals, you may wish to reassess your long-term goals. Perhaps your goals will change slightly, or you will discover that you have exciting, new goals. Therefore, it is important to complete a “goal check-in” with yourself on a regular basis, and to track your achievements/areas for improvement.

Note: Please review the following example of a S.M.A.R.T. goal for a student who wishes to complete a short-course triathlon race (750-meter swim, 12-mile bike, 3.1-mile run).

S.M.A.R.T. Goal Example: Triathlon

- Specific – Student includes the specific factors s/he will target in training: endurance front crawl swimming sets, endurance cycling sessions, endurance and sprint running sessions.

- Measurable – Student identifies the amount of training s/he will engage in: 45-minutes of moderate-paced swimming once per week, 30 minutes of moderate-paced cycling twice per week, and 2 sessions of running (variable duration at either a moderate- or sprint-pace) per week.

- Achievable – Student creates goals which s/he feels confident that s/he can achieve.

- Realistic – Though the student may feel confident that s/he can successfully swim for 45-minutes continuously with proper training, s/he may start the training regimen to account for foundational fitness levels. In order to be realistic, the student may initially break the 45-minute swim into 15-minute bouts. As the student’s fitness levels improve, s/he may gradually increase the duration of the swimming bouts.

- Time-Bound – In this example, assume the student starts training for the triathlon 6-months prior to the race. Therefore, the student decides to set timely goals for each part of her/his training regimen (i.e., achieve desired race-pace for swimming/cycling/running 1-month prior to the race; log a certain number of miles per week throughout the 6-month training program). It is important to note that each individual’s S.M.A.R.T. goal will be highly personalized to her/his foundational fitness levels, abilities, and preferences.

Comprehension check:

Provide an example of a S.M.A.R.T. physical activity goal. Is your goal specific? Can you measure and keep track of your progress? Is your goal achievable? Did you set a realistic goal? Did you indicate a time-frame in which you wish to achieve your goal by? (Hint: creating a goal that is too challenging to achieve in the time-frame specified may be discouraging. Remember, achieving short-term goals may assist you in achieving long-term goals. Set goals which can be reasonably attained, yet require your best efforts).

Works Cited

Bandura, A. (1994). Self‐efficacy. John Wiley & Sons, Inc..

CDC. 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/adding-pa/barriers.html

Fagard, R. H., & Cornelissen, V. A. (2007). Effect of exercise on blood pressure control in hypertensive patients. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation, 14(1), 12-17.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705.

Marshall, S. J., & Biddle, S. J. (2001). The transtheoretical model of behavior change: a meta-analysis of applications to physical activity and exercise. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 23(4), 229-246.

Moore, M., & Tschannen-Moran, B. (2010). Coaching psychology manual. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

Prochaska, J. O., & Velicer, W. F. (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12(1), 38-48.