20 Techniques of Orchestration

Techniques of Orchestration

Simply put, orchestration is the timbral articulation of musical ideas, and is as important to conveying to a listener the expressive intent of the composer as an inspired melody, a finely crafted harmonic progression, or a vital rhythmic impulse. Orchestration, despite the connotation of the word, is applicable to any given instrument, voice, or group, whether it be an arrangement for a symphonic ensemble, string quartet, solo piano, choir, or even electronic sounds. The composer’s obligation transcends mere assignment of the parts to instruments that have the compass to convey the music: one must bring transparency to the textures and illuminate the dramatic qualities, as well as sufficiently support the acoustical needs of the ensemble and resourcefully utilize the idiomatic instrumental possibilities that lie within. As such, there is no single manner that can provide the composer with a solution to all of these requirements within every work. Effective orchestration depends as much on the musical style at hand as it does personal taste and an ear for experimentation.

The brief examples that we intend to orchestrate below will explore some of the fundamental stylistic approaches that composers have cultivated from the Common Practice onward.

Index

Orchestration Types

A. Type I Orchestration

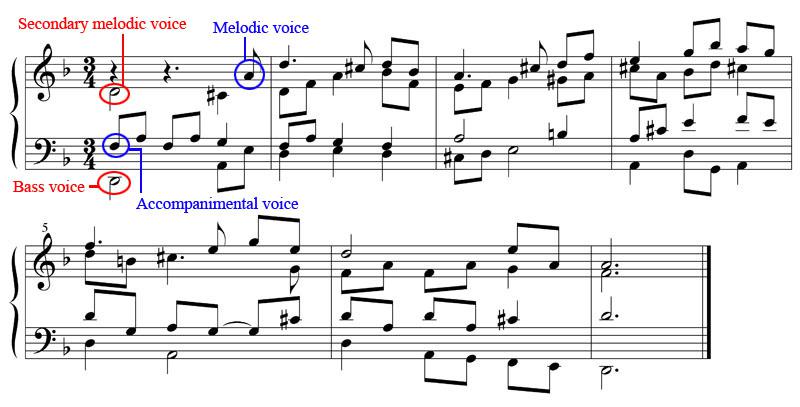

Type I orchestration is a hierarchical treatment of the music within an ensemble: each layer of activity is, in effect, portrayed by an instrument or instrumental group with a significant degree of regularity throughout a particular texture. When a new texture arrives in the course of the piece, a different hierarchy can be established, similarly to the compositional concept within a sonata that calls for contrasting thematic types. Let us begin by writing a short score with a clear delineation between the function of the four component voices: 1. the primary melodic voice, 2. a secondary melodic voice that both supports the upper line while bringing an added dimension to the harmonic lower parts, 3. an accompanimental voice, and 4. the bass.

Listen: Track 48

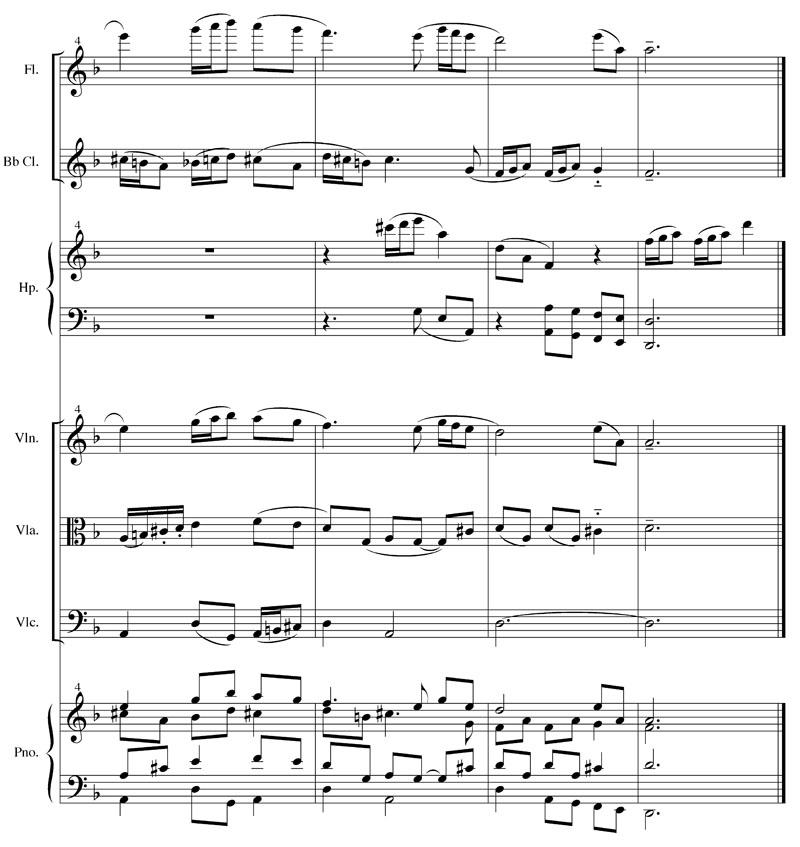

In our arrangement (for flute, clarinet, harp, and string trio), the strings form the core of the texture, with the cello performing the bass, the viola the accompanimental role, and the violin the melody. However, to reinforce the melody as the principal line in this hierarchical structure (being clearly homophonic), it is doubled an octave higher by the flute. This provides the emphasis needed to clearly articulate the melody while still binding it with the overall textural orchestration.

The secondary melodic voice needs to be clearly distinguished as it is an inner voice and could be aurally lost if assigned to another string instrument. The choice of a clarinet to fulfill this role was made because of its acoustic strength and lyrical flexibility throughout the given tessitura while avoiding the more strident tone an oboe would produce in this lower range. The flute was also avoided because it is at its weakest in this range and would be difficult to discern in the interior of the texture.

In addition, the concept of adding compositional elements such as textural motifs is explored here from the outset. Note the oscillating thirds in the accompanimental voice are reconceived as two sixteenths + eighth note patterns. This motif is judiciously incorporated in varying instruments throughout, bringing with it a rhythmic continuity otherwise absent in the original. The source score, conceived at the piano, should not in any way be held as entirely sacrosanct. Indeed, it is a part of the orchestrator’s initiative to discover ways to, in effect, translate the raw material of a composition into a new entity while maintaining the character of the original.

The harp is employed primarily as an acoustic and rhythmic embellishment of existing instrumental parts. However, because of its large compass, it is freely displaced between the treble and bass registers. It also is used in the closing bars to emphasize the descending scale in the bass (which is removed from the cello line entirely) and additional final statements of the rhythmic motif in the treble.

Finally, phrasing and articulation is incorporated into the instrumental parts to maintain a lyrical quality throughout each layer of activity. A key idea for the orchestrator is to sing each part aloud to find the correct phrasing needed. Dynamics are avoided in this exercise in keeping with a simple arrangement that seeks equal balances between the parts over a type of ‘superimposed equalization’ that differing intensities can provide.

The score below is untransposed. The original piano part is reprinted for reference (it is not part of the arrangement).

Listen: Track 49

Orchestrating to Illustrate Structure. Another way that orchestration can be creatively employed is to use it to help elucidate the form of a piece for the listener. In the following ternary bagatelle for piano, sections A and B share a similar texture. Therefore, a different approach to the instrumentation at this structural change will be explored. In addition, although the A section returns verbatim following the central portion, there is nothing prohibiting the orchestrator from enriching this final part and straying from an identical arrangement as heard at the outset.

Listen: Track 50

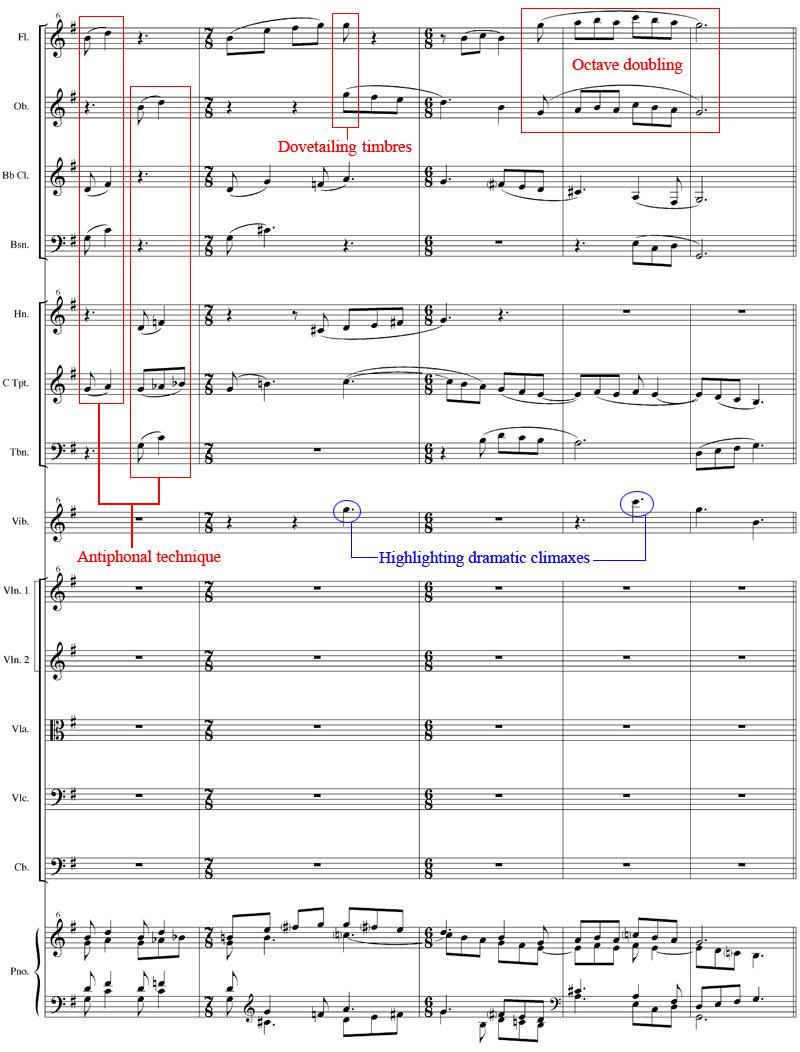

Scoring Strategy. When a composer is conceiving of an ensemble, it is worthy to first plan on how it will be engaged in the work at hand. We have already decided that to make a greater distinction for the three similarly textured sections of our piece, each will be accorded a unique orchestration, while carefully maintaining an organic unity with the whole. As such, four solo winds and brass will be supported by a small string ensemble. A vibraphone will be added, as the rich tone of its sustained attacks will blend well with the mood of the piece being arranged.

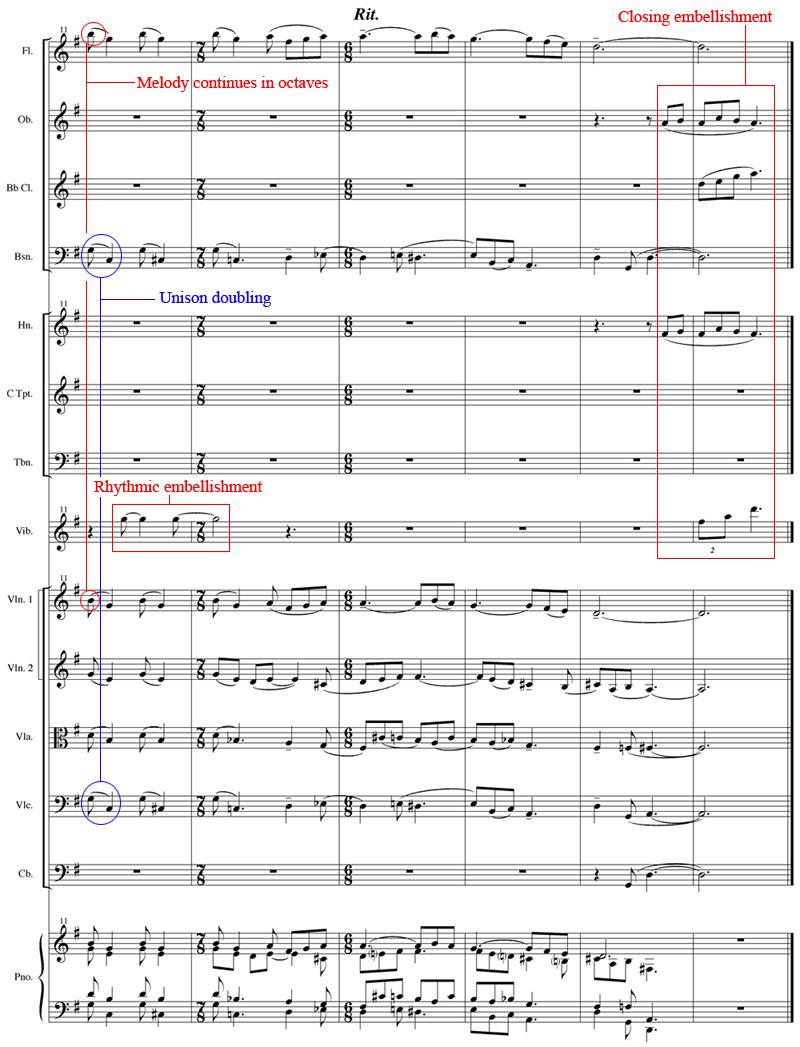

One notable timbral choice made for this arrangement is the specific instruction for the string parts at the opening to play sul tasto (to bow over the fingerboard) which brings with it a gentle, distant tone to the ensemble. Note that the contrabass is reserved throughout this piece only for the cadence points of the A sections; a confident orchestrator understands that instruments should be used only when they are needed in the piece while over-use will detract from the desired effect. Indeed, some instruments can be reserved by the composer to support only specific functions (as observed here) while remaining silent for the rest of the work.

In bar four a suspension occurs between the violins but which was an appoggiatura in the original piano score. This was changed because the piano needs to rearticulate the note in order for the dissonance to be expressed with sufficient strength, whereas an instrument capable of producing sound with sustained intensity does not require another attack.

Section B is distinguished through our use of only the winds and brass for the primary aspects of the arrangement while the strings are tacit. Since these instrumental groups provide the composer with a wide variety of timbral choices, we will avoid the simple, although effective, approach of the string arrangement from the first section. Analyzing the music at hand, we notice that each phrase begins with a series of melodic repetitions (supported by subtly different harmonies). Therefore, we can employ an antiphonal technique wherein we will alternate how each segment is arranged between two instrumental sub-groups.

In bar seven we will dovetail two instrumental lines (flute and oboe) to seamlessly transform the timbral quality of the melodic voice. These same two instruments will reinforce one another in octaves at the conclusion of the section.

Also in the central portion of our brief piece the vibraphone is introduced, but only to emphasize certain important pitches within the melodic contour. It continues on into the final section, here primarily as a rhythmic embellishment.

In the return of section A the flute persists in its doubling of the melodic line an octave higher, thus producing continuity with B. The bassoon introduces a new timbral dimension to the arrangement by reinforcing the cello (in unison). This is also used to create a balance with the now stronger intensity of the treble parts.

Unlike the piano original, which concludes identically as the opening phrase, in our orchestration we have added a final embellishment drawn from the brass (absent to this point in this section), winds, and percussion.

As before, the printed score below is untransposed. The original piano part is included only for reference as it is not a member of the ensemble.

Listen: Track 51

B. Type II Orchestration

At the dawn of the last century, composers began to explore unique instrumentations for their ensemble works. However, many persisted in applying type I orchestration (or a development thereof) to their new styles of music, even though this approach had sprung from 18th and 19th century concepts and methods of organization. Some composers recognized that in order to support a new musical syntax, it was necessary to cultivate a method of orchestration that would provide an appropriate timbral realization. The result of this was the evolution of type II orchestration.

This is essentially an analytical approach that is particularly suited to works that rely on elaborate motivic manipulation or involved polyphonic treatment. As such, one of its primary goals is utilitarian: to break down the surface complexity through exacting timbral choices assigned to (usually short) portions of the materials. One analogy is to imagine adding specific colors to a complex web of originally monochromatic lines in order to illuminate the intricate images buried within the dense design, which in turn better reveal the overall form.

Often associated with this type of orchestration is a kaleidoscopic use of the ensemble, rather than creating a hierarchy wherein each instrument serves only a specific function within the texture. Doublings are normally absent, in order to concentrate the listener’s ear on clear, pure timbres. Anton Webern (1883-1945), who originally implemented this approach in his angular dodecaphonic music, envisioned its potential to help elucidate complex material regardless of style. His arrangement of the six-part fugue from J.S.Bach’s Musical Offering is convincing testimony to the broad applications type II orchestration presents to the composer.

Often the term klangfarbenmelodie (German: sound-color-melody) has been wrongfully associated with the kind of pointillistic approach espoused here. Arnold Schönberg, who coined the term, originally used it to describe a work in which timbral manipulations would be substituted for motivic and harmonic development. The term is better used in conjunction with type III orchestration.

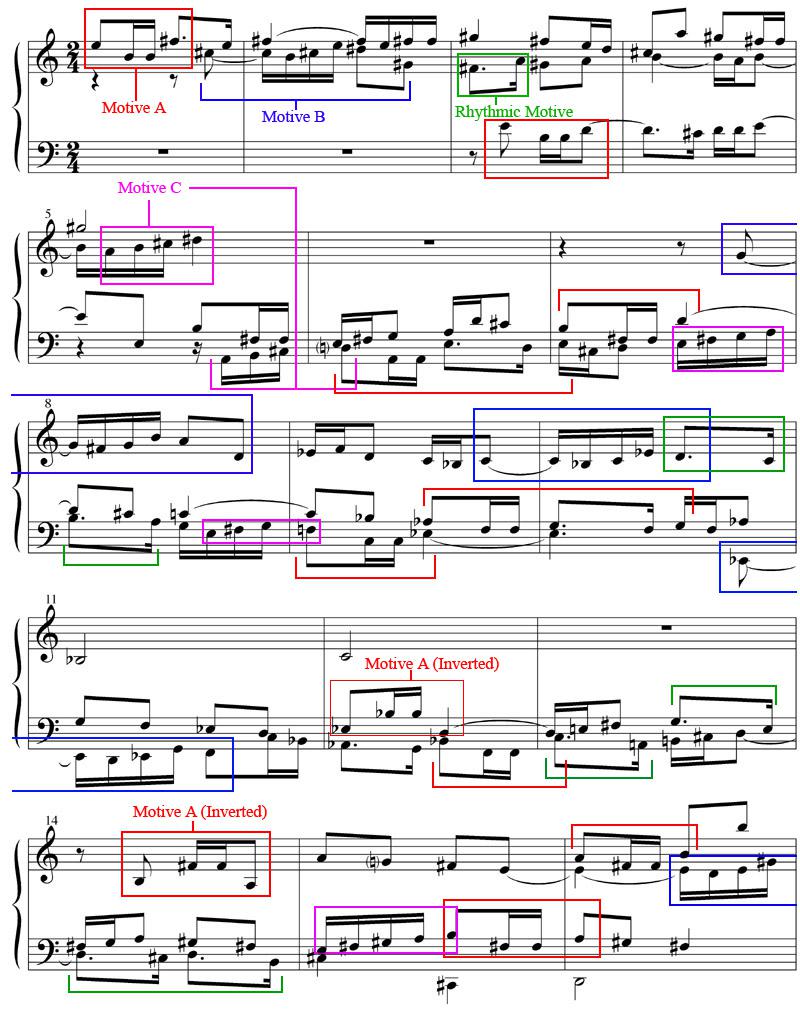

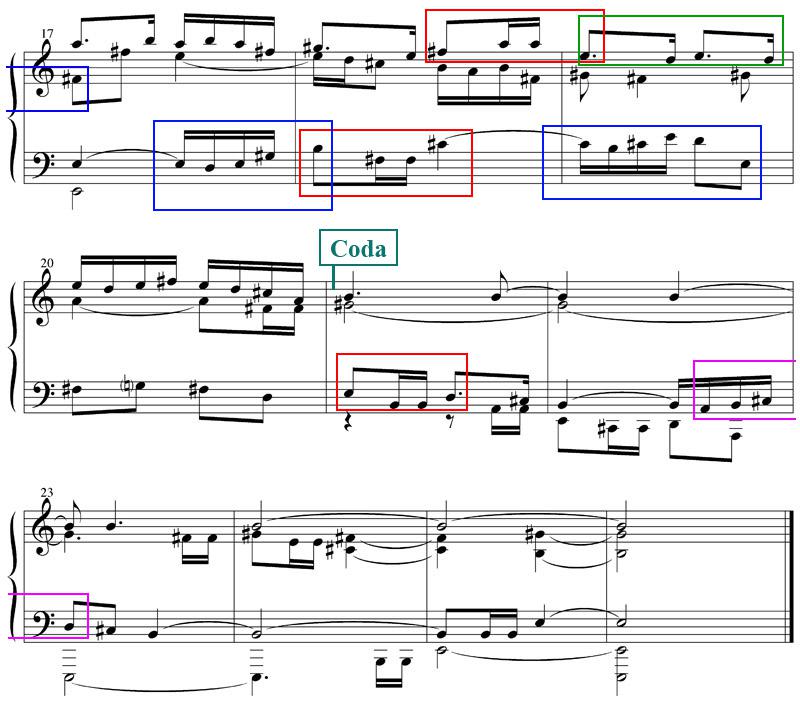

Appropriate Musical Choices for Type II. We have chosen to compose a piece for piano that integrates brief motivic material into a polyphonic texture. The development of the piece will be analyzed regarding the manner in which the motives interact. This will enable us to demonstrate how this particular type of orchestration can be advantageous to the composer.

Listen: Track 52

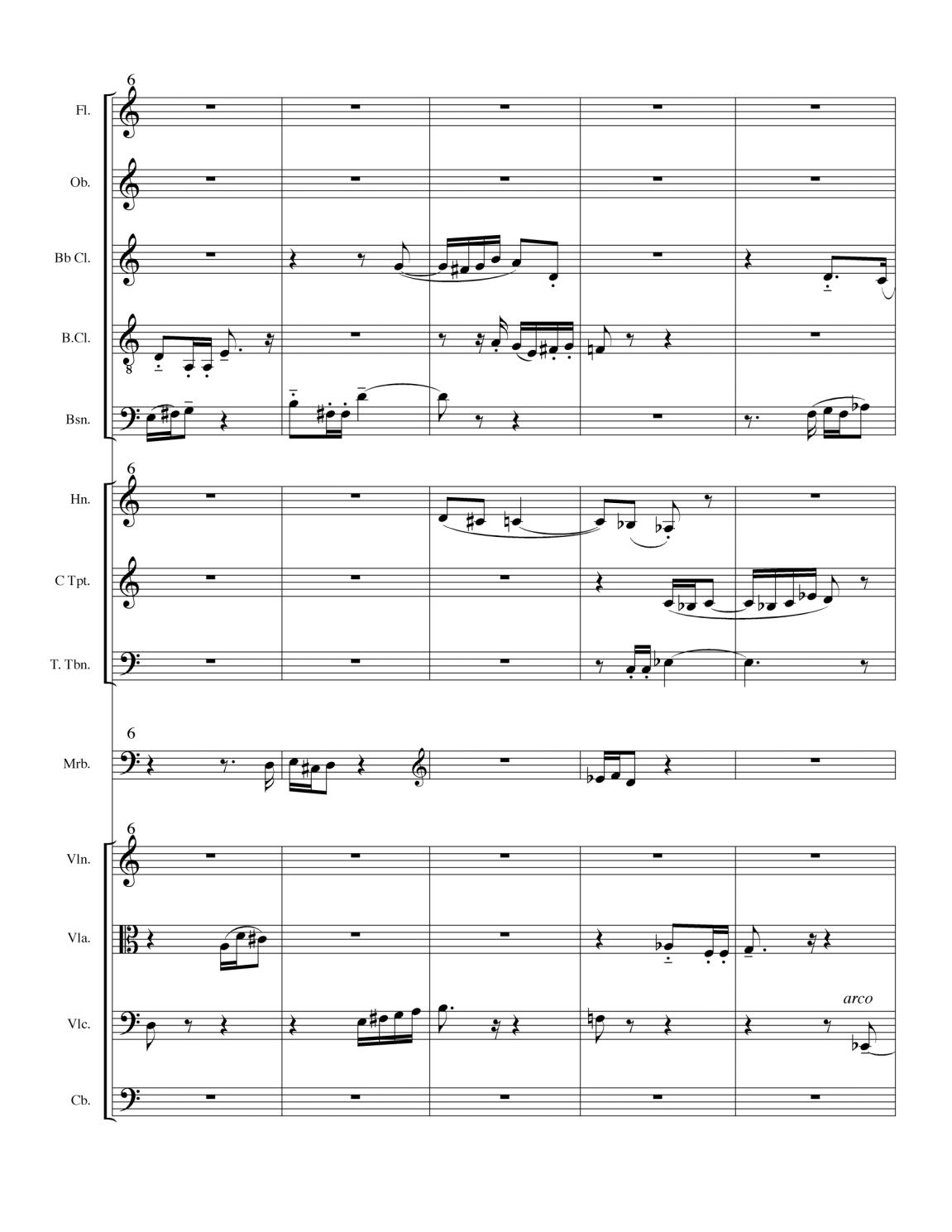

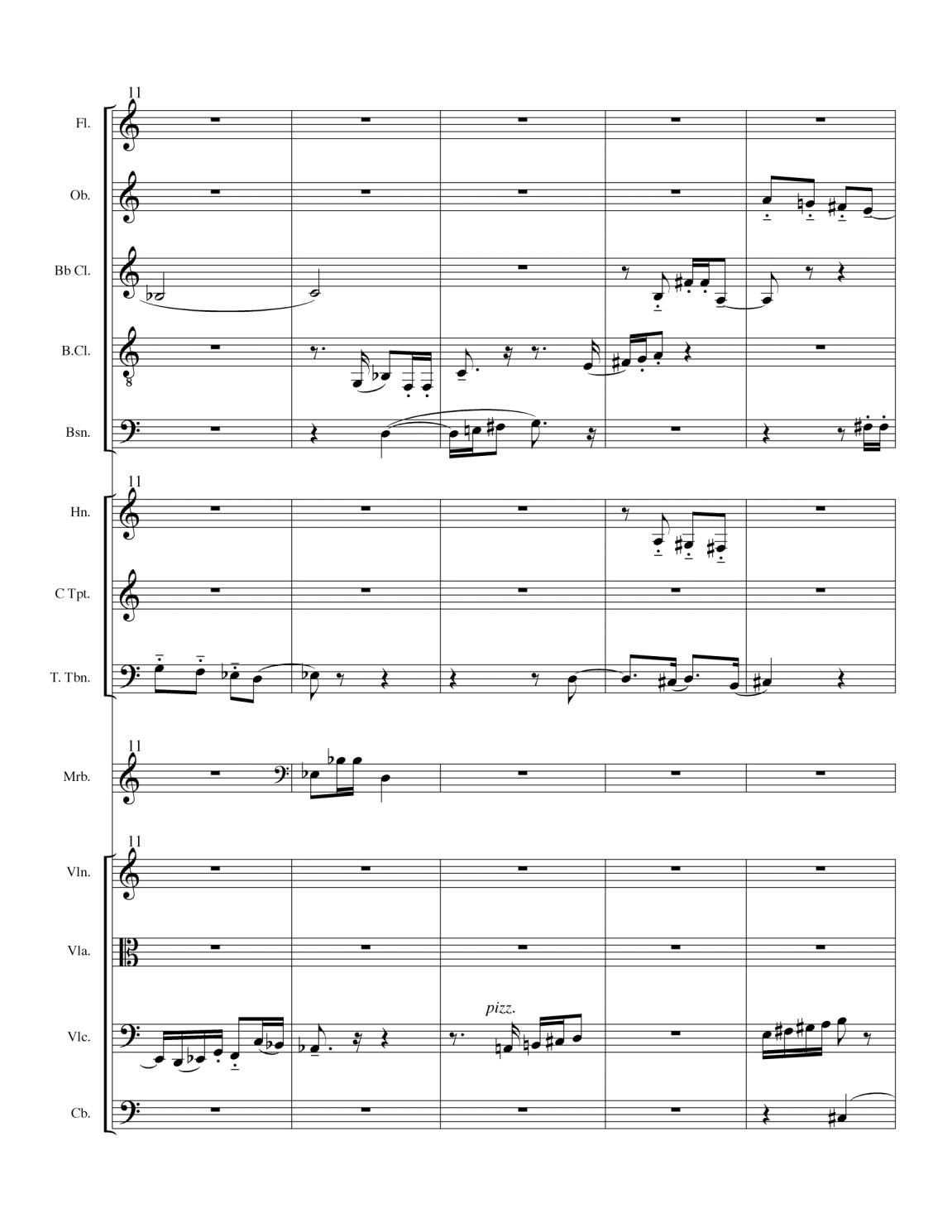

Applying Type II Orchestration. We have chosen an ensemble of flute, oboe, clarinet, bass clarinet, bassoon – horn, trumpet, trombone – marimba – violin, viola, violoncello, and string bass. The inclusion of the bass clarinet is to provide an alternative wind in the lower register to the bassoon. This is in order to support the clear articulation of one of the prevailing motifs that features a quickly repeated sixteenth note. The marimba was preferred over the vibraphone for similar reasons, being that its sharp, resonant attack, brief sustain, and sizable range, allow it the flexibility required within the sparse overall texture.

The articulations and phrasing were afforded particular consideration in this arrangement. Note that the cello is instructed to perform two ways: arco and pizzicato. The pizzicato orchestration is employed to bring greater prominence to the less distinctive motive C, while its quality of attack can be echoed by the marimba.

Little alteration is introduced into the original material itself, save for a few closing additions. Most of the attention to the arrangement was given towards maintaining a clear presentation of the contrapuntal materials through ever-changing, though coherent, ensemble combinations.

Listen: Track 53

Note: the score below is not transposed.

C. Type III Orchestration

The basis of type III orchestration can be viewed as one that diametrically opposes type II, which encourages a pointillistic use of the ensemble, while negating type I, which calls for a hierarchical interaction between the instrumental groups. This is because the style of music that type III best supports is wholly unsuited to either style that type I or II is normally applied. Indeed, the music of type III is c conceptually driven by the shaping and unfolding of timbral combinations, which acts as the fundamental organizational structure and compositional premise, in lieu of melodies/themes, counterpoint, passagework, or harmony (in the traditional sense). The overlapping and juxtaposition of the instruments often result in the obscuring of individual timbres in favor of the creation of unique ensemble sounds. As such, we cannot begin with a ‘short score’ or piano original, but must compose directly with the ensemble.

Although many of the principal methods for organizing music are lost to us in this genre of (primarily) instrumental writing, composers have developed techniques that maintain a clear sense of narrative and drama derived largely from timbral manipulation. Although Arnold Schönberg (1874-1951) explored some of the elemental ideas that relate to type orchestration in his non-tonal experiments of the pre-World War I era klangfarbenmelodie (German: sound-color-melody). Most notably, the third composition from his Five Orchestral Pieces Op. 16 (1909), employs type III orchestration at the core of the glacially shifting harmonic blocks. It was only in the post-World War II period when composers such as Giacinto Scelsi (1905-88), Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001), and Krzysztof Penderecki (b. 1933), began to explore the technique extensively.

One such technique found in the literature focuses the compositional activity on small pitch ranges at a time (such as a minor third), and some on only single notes. In the orchestral bagatelle that we have composed, there are two pitch regions separated by a tritone, A and Eb, around which instrumental activity pulses. Instruments oscillate around these centers, their juxtapositions creating a fluctuating and irregular pattern of strident sonorities and tensionless unisons. In this style it is part of the compositional process to finely regulate this dramatic and intricate interplay so that the result supports the desired expression.

The instrumental combinations are continually in a state of flux, bringing a carefully tempered, timbral vitality to these close clusters of pitch variations. The dramatic shift from the higher tessitura instruments to the lower, and finally the ‘cadential’ passage in the middle register, reflects the tritonic motion from the opening A to the closing Eb. However, throughout these changes, the complete array of available instruments illuminates and provides ornamental substance to this seemingly simple outline.

Listen: Track 54

Note: the score below is not transposed.