1 Composing a Basso Ostinato

Basso Ostinato

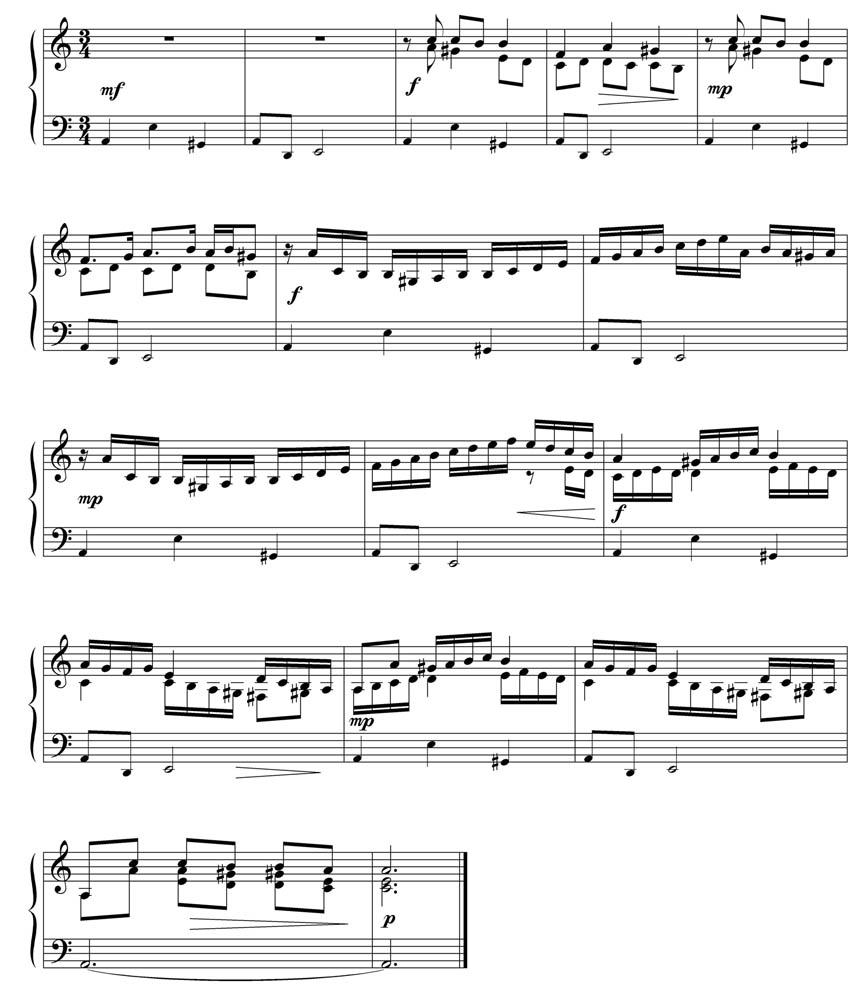

The following is a brief model in composition that is intended to provide the student with a step-by-step approach to writing a simple piece based on a basso ostinato using the vocabulary of the Common Practice.

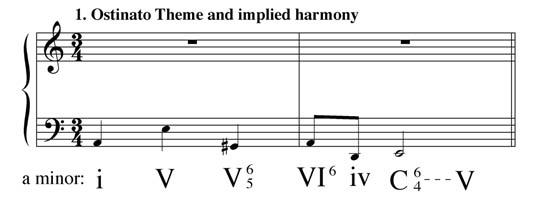

The first step entails arranging a bass line that at once has a distinct melodic profile itself, and that has the ability to imply a logical harmonic progression beginning with the unambiguous establishment of the tonic. Some examples of basso ostinati from the Common Practice Era conclude each variation with an authentic cadence while others provide a half cadence to enable a dovetailing into the successive variation. The model composition provided here follows this later format. Although, of course, this progression need not be used as the basis of every variation, it is useful for the beginning composition student to develop creativity through restrictions.

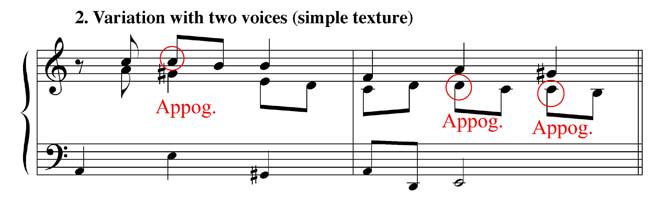

Next, the first variation is composed, making use of a simple, exposed texture. This variation should avoid elaborate use of non-harmonic tones to enable the progression to remain transparent. In terms of drama, the development of any variation form from the Common Practice Era (and many from the Modern Era) tend to proceed from the unassuming to the complex in waves wherein climaxes are offset by sudden drops in activity only to build to greater climaxes.

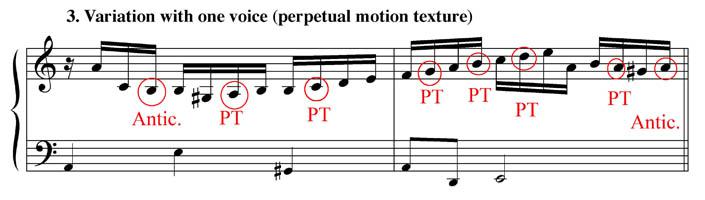

A further development can involve lessening the number of voices, thus allowing only one or two to fill out the harmonic ideas through a fluid texture of ‘perpetual’ motion. Here, more substantial use of non-harmonic tones is necessary unless arpeggiations are employed.

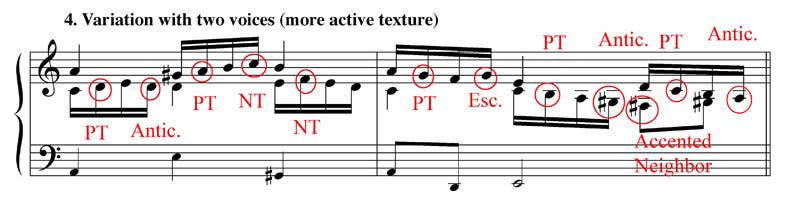

Returning to a denser texture in the following variation, activity can be apportion to multiple voices in alternating patterns to sustain the momentum of the previous section.

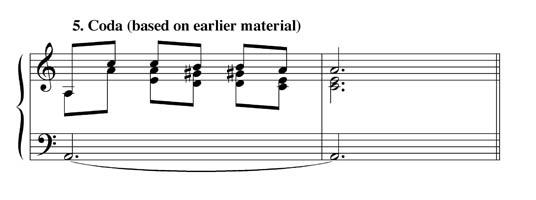

Finally, a coda is added to bring closure to the harmonic progression. In this example, the material has been drawn from the first variation, however use of new, quasi-improvised material is perfectly suited to this style.

Complete score. When brought together as a unit, many examples (including the present model) adopt the principle of ‘paired variations’ wherein each section is repeated, albeit with some degree of modification or dynamic change. As an assignment, the student is invited to compose a new set of variations using this same bass line and progression, or a new one can be composed of similar length and dimensions. Additional concepts composers have incorporated into their basso ostinati have included the transference of the bass line to another voice in select variations, modulating the bass line to different key areas (notably the relative major/minor), a metrical or rhythmic alteration of the ostinato, and the use of imitative structures juxtaposed over the ostinato.

Listen: Track 1

Composing a Basso Ostinato with Tonicizations and Modulations

Note that these examples are modeled after the English Baroque practice of implementing a ritornello variation (or a variation that is used as a refrain – see the Grounds of Henry Purcell). This is an interesting alternative to the paired variation model that is more commonly found in the German Baroque (see Buxtedhude’s Chaconne in e minor). Student composers are encouraged to explore both models.

This first example incorporates a tonicization to the supertonic key region within the course of a variation. The second example integrates a modulation (to the relative minor in this case) through a modification of the basso ostinato.

The following listening list is provided for the student to explore numerous outstanding examples of how this form has been adapted from the Baroque through the present.

List from the Common Practice

Johann Sebastian Bach: Passacaglia and Fugue in c minor (organ/pedal harpsichord)

Heinrich Ignaz Franz Von Biber: the last of the Rosenkrantz Sonatas (violin solo)

Johaness Brahms: Fourth Movement from the Fourth Symphony (orchestra)

Dietrich Buxtehude: Passacaglia in d minor (organ) – features a modulating ostinato

François Couperin: Passacaille from the Ordre no.8 (harpsichord)

Girolamo Frescobaldi: Cento Partite sopra Passacagli (keyboard) – features metrical and rhythmic alterations of the ostinato.

G.F. Handel: Passacaglia from the Suite no.7 in g minor

Georg Muffat: Passacaglia (organ)

Henry Purcell: Chacony in g minor (string ensemble)

Max Reger: Introduction, Passacaglia and Fugue in e minor , Op. 127 (organ)

List from the Modern Era

Hugo Distler: Chaconne from the Partita “Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland“ (organ)

Philip Glass: Act I, Scene 1 from Satyagraha (opera)

Leopold Godowsky: Passacaglia on the Opening of Schubert’s ‘Unfinished’ Symphony (piano)

Paul Hindemith: Final movement from the Viola Sonata, Op. 11 no. 5

Dmitri Shostakovich: Passacaglia from Violin Concerto in a minor (Op. 77)

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji: section three of the Interludium Alterum from Opus Clavicembalisticum (piano)

Ronald Stevenson: Passacaglia on DSCH (for piano)

Anton Webern: Passacaglia Op. 1 (orchestra)