8 Composing a Theme and Variations

Theme and Variations

One of the foundations of instrumental music for the past four hundred years has been the composing of variations based on either a newly created theme or a melody from a folk song, the literature of sacred music, or another composer (past or present). We have already discussed a couple varieties of the genre of variations, namely the basso ostinato and chorale settings. However, the approach we will take here will differ in context and structure.

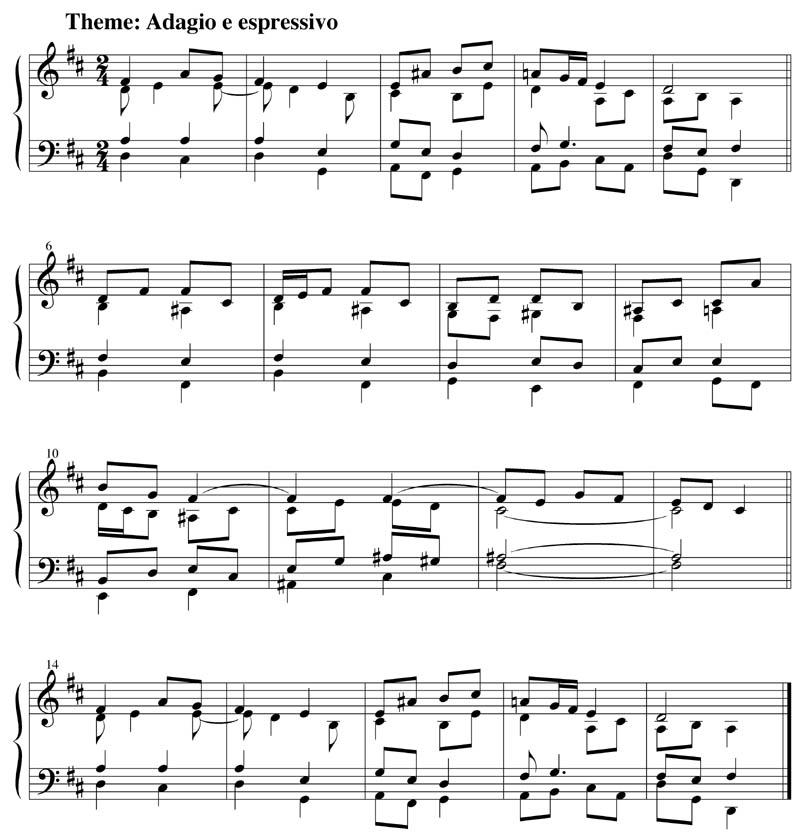

Theme. It is important to take as a theme some material that has a strong profile, one with a recognizable character that will be distinct over the course of the variations to come, or simply one that you are particularly attracted to. For sake of example, we have chosen to use the short ternary piece composed in a previous lesson.

Listen: Track 5

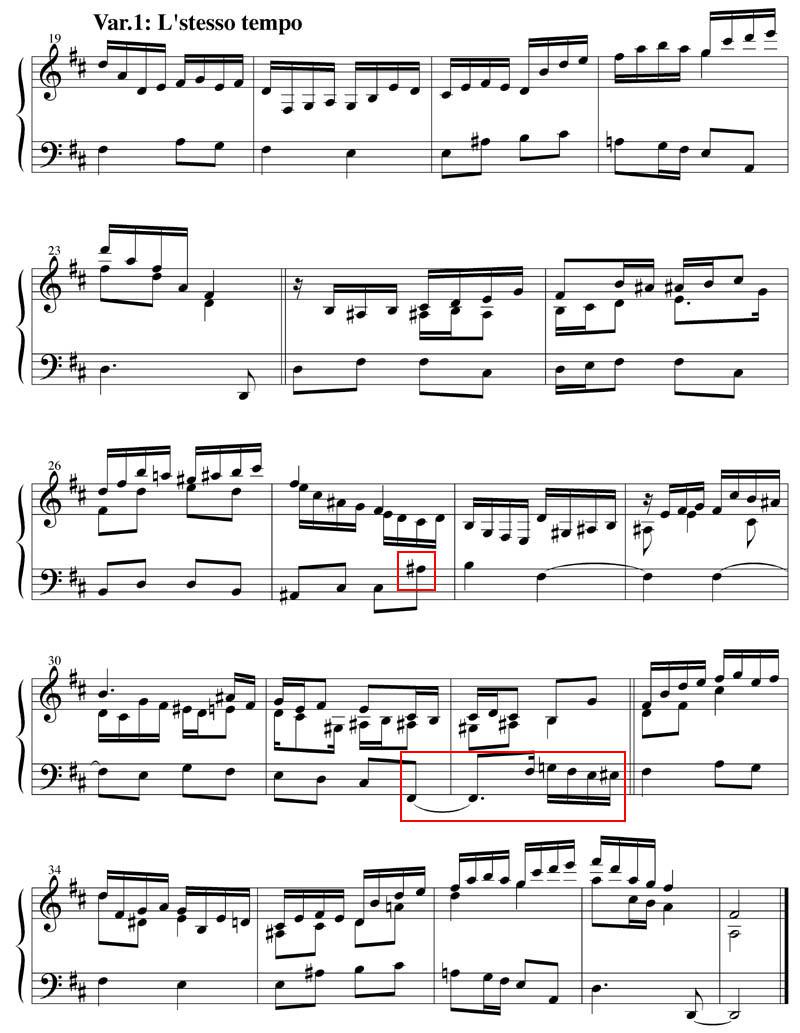

First Variation: Displacement of Theme. Here we have taken the lyrical melody of the theme and placed it in the bass (with a couple of alterations marked below in the score); the displacement of a melody from the treble to an inner or lower voice is a typical device in preparing to compose a variation. One method involves writing the part out entirely on the manuscript first, then composing around it as appropriate. Although many of the harmonic ideas of the theme are used again here, the flowing sixteenth note texture of the upper parts defines the character of this variation.

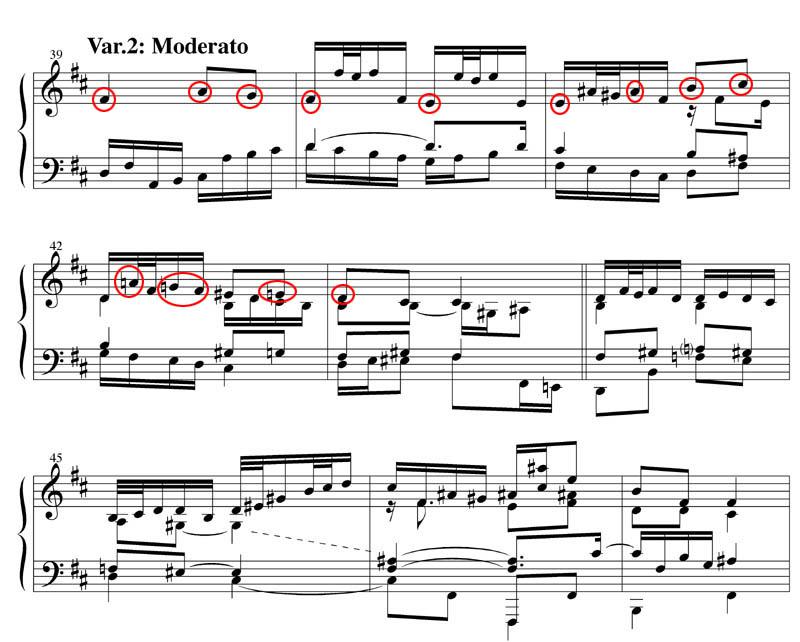

Second Variation: Ornamented Theme. In this variation the theme is broken into three sections (ABA). The first section of the melody is interpreted with embellishments (note the highlighted notes of the original theme). As well, instead of arriving at a D major cadence, as in the original, here the A section concludes with a secondary dominant preparing for a modulation to b minor in the next section. B is interpreted with greater license, creating shorter motifs from the original.

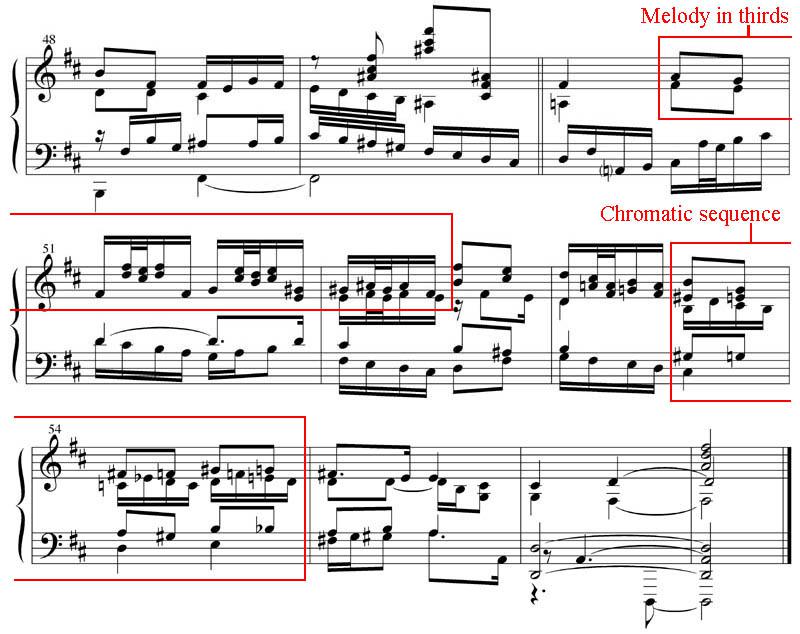

The repetition of the A section is further heightened by using thirds to amplify the melodic elaboration. However, since the original A section of Var. 2 did not cadence in the tonic key, here we must now find a new way of returning to D major. To solve this problem, the passage that prepared the original cadence is chromatically sequenced to reach the dominant of D (A major) instead of the dominant of b (F#).

Third Variation: Change in Meter. A metrical alteration can be used to change the inherent character of a theme. Here our duple meter melody is modified into a triple meter variant. In the score below we have highlighted harmonic passages worthy of note; especially as we pass through more variations, keeping too closely to the original progressions can become tiresome. Of particular interest is the use of the Neapolitan chord in the B section. One structural divergence from the original takes place at the first cadence point: the conclusion of A does not occur until the downbeat of bar 62, which is also the beginning of B. This creates a sense of seamless integration of the two sections.

Fourth Variation: Modal Change. Although a more complex issue when there is a modulation involved, as is the case here, the use of the parallel key can create a sudden change in the mood of the theme.

Fifth Variation: Fugue. It is not uncommon to interpolate contrapuntal structures into the course of a set of variations (such as canons, fugues, etc.). However, regarding how much of the theme should be used in such a context becomes the point in question. Some composers choose to incorporate only the very recognizable opening of the melody, while others use more substantial segments or break the theme up and use portions at various junctures in the course of the variation. Here we’ve used only ideas from A as material for the subject but a brief hint of B occurs in the course of the development. For more information on how to compose a variation using fugal structures, see the related chapter on the subject.

Ending the Variations. Here we have adopted the practice of some composers who of employ, as a last ‘variation’, a recapitulation of the original form of the theme (with or without some modifications) as a way of creating a sense of closure to the piece.

However, this is not a requirement for a set of variations; a culminating, climactic variation is also an alternate suggestion. The number of variations, their order, the style – or changing styles – of the series of variations, whether or not they are integrated with one another, are all variables at the discretion of the composer. The important concept for the student composer to remember is to explore the potential expressive content latent in any theme. As such, a theme and variation format can be an excellent method of developing one’s ability to adapt a melodic idea to many different contexts.

Listen: Track 22