7 Composing Chorale Settings

Chorale Settings

The chorale, as with any other canus firmus, provides the composer with some a priori (or pre-existing) material from which new music can be composed. In fact, cantus firmus based writing was one of the first methods that Western composers used to develop sophisticated musical structures from the Medieval era on. The practice of setting chorales distinguishes itself through the specific forms that composers began applying to them in the seventeenth century. Often contrasting sets of settings are grouped together to form partitas. We will explore some of the prevalent forms of chorale arrangements through creating new settings of one of the oldest chorales, Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland. This Lutheran chorale originated in the early sixteenth century as an altered, metrical version of the fourth century Ambrosian hymn Veni, Redemptor Gentium.

Index

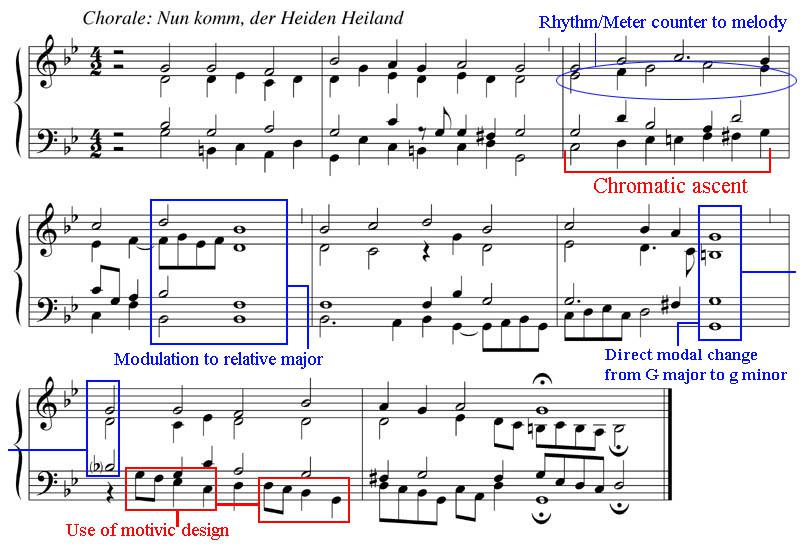

A. Original Setting (Samuel Scheidt)

In this version by the veritable father of the North German school of organ, Samuel Scheidt (1587-1654), we find a more vocally oriented and contrapuntally interesting method of supporting the cantus than exhibited by later composers, who too often derive voice parts from formulaic harmonic progressions in lieu of truly independent lines. As well, with the Scheidt we will observe a more appropriate modal treatment to this Renaissance cantus. Points of interest are here marked in the score.

Listen: Track 18

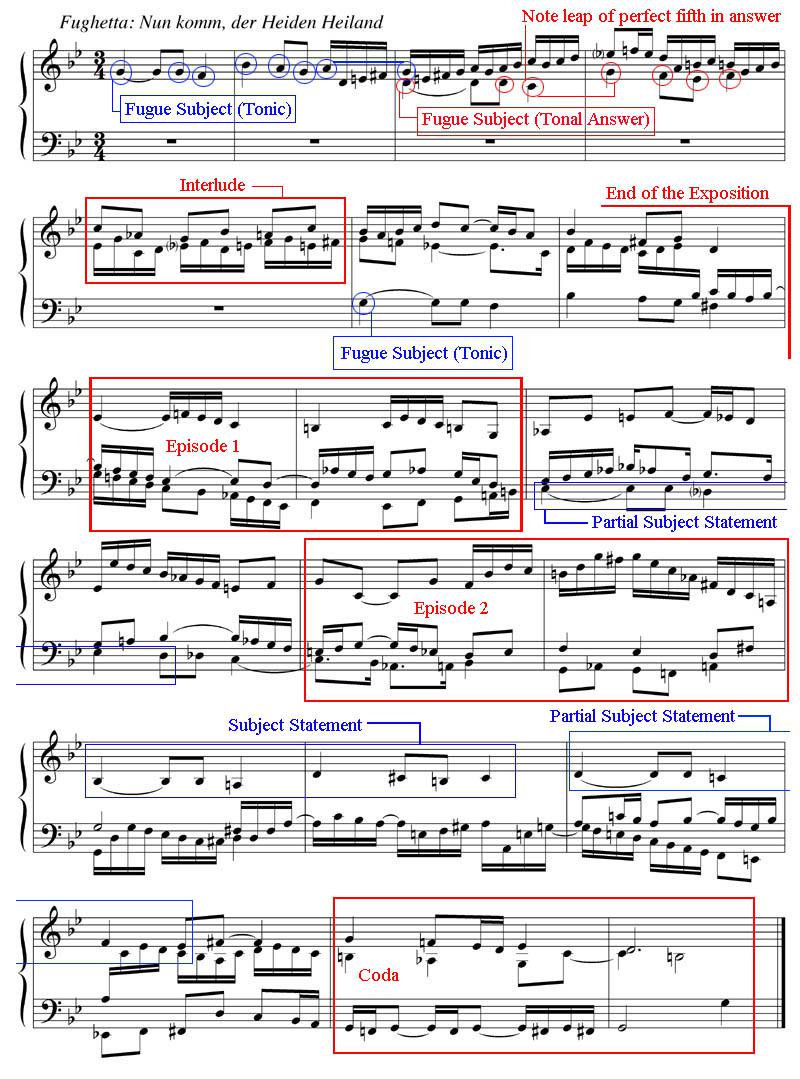

One of the forms adapted to chorale settings is the fugue, or, as here, a fughetta (meaning a short fugue). The chorale fughetta is ordinarily derived only from the opening musical phrase (that typically identifies the particular chorale). Here, we have slightly altered its rhythm and meter to create a distinct profile to our subject, emphasizing the notable perfect fourth leap. In the chapter on Composing a Fugue, a comprehensive step-by-step approach to the form is explained. The piece here will be used only to illustrate the particulars of how a chorale phrase can be transformed into a subject and expressed contrapuntally. Other aspects of fugal composition worthy of note will be indicated below.

Points:

The answer in this exposition is a tonal answer. This means that although it maintains the contours and rhythm of the subject, it will be slightly modified to support the harmonic structure needed. The perfect fourth leap of the subject in this situation becomes a perfect fifth.

At the conclusion of the answer there is an interlude (bar 5). This is a brief sequence used to bring the harmonic region back to the tonic, and in so doing preparing the final entrance of the subject in this exposition.

Although following the exposition, episodes separate the next two subject entrances, this is not always needed. In fact, the two final subject entrances of the piece are placed back to back – and even in the same voice – to create a dramatic moment in anticipation of the coda.

Listen: Track 19

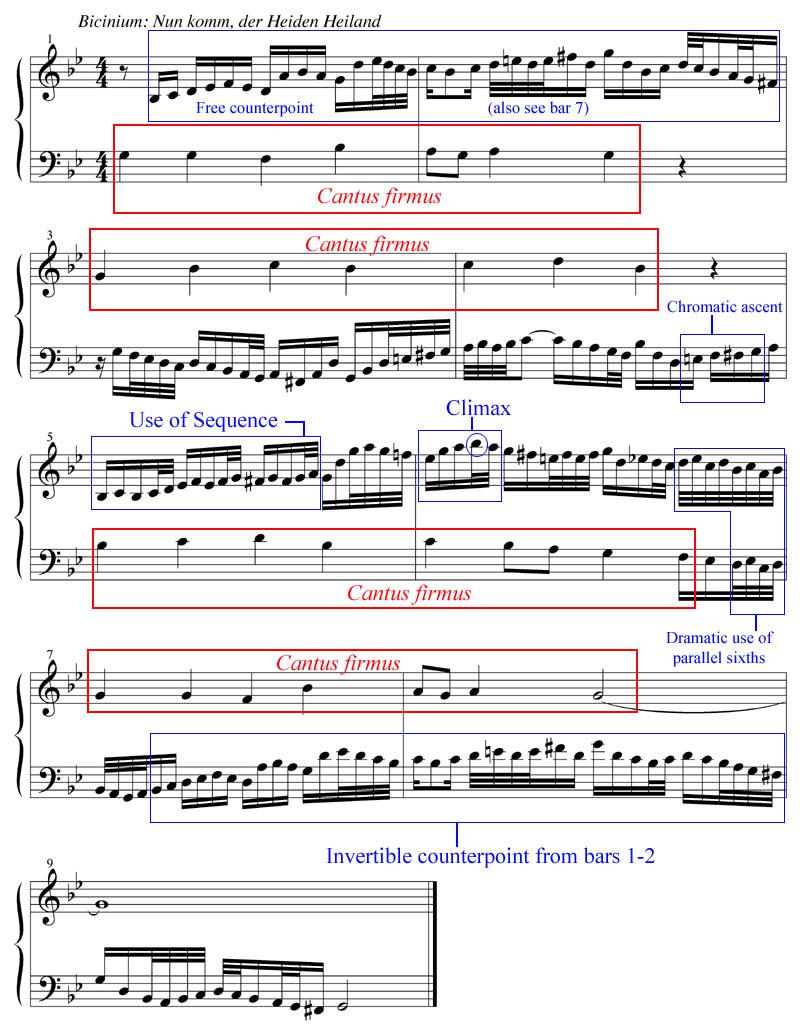

The bicinium is one of the more antiquated approaches to chorale settings. Reaching its height in the organ settings of Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562-1621) and Samuel Scheidt, it virtually disappears by the late seventeenth century. Dormant for over two hundred years, it began to find new life in the second quarter of the twentieth century in the hands of composers such as Hugo Distler (1908-42) whose interest in the early Baroque brought forth a revival of its forms and manner of developing materials.

The bicinium typically alternates each phrase of the chorale (in or close to its original form) between two soloistic voices. Original material of a quasi-improvisational character is composed against each phrase in the free voice. These passages usually consist of intricate and ornate filigree, often (but not necessarily) with some motivic connections. It is the very bare quality of this form that provides for its unique character, and along with it, special demands on the composer to maintain interest and drama within such an exposed texture. Implied harmonic progressions should, however, remain the basis for the contrapuntal extrapolations and thus guide the logic of the new material. Overall, what should be remembered most is that the bicinium is at its best an engaging interplay between two voices of absolutely equal significance and fluidity. Although there are no occurrences of voice crossings in our composition below, this is something that does not need to be avoided as bicinia are normally performed on two separate manuals.

We have chosen to begin with the first phrase of the cantus in the bass, cutting short the last note just a bit to allow for a brief change in texture. The interaction between sixteenth and thirty-second note rhythms displayed in this initial counterpoint will become the impulse for the remaining phrases. Note that the final beat of the treble line in bar 2 descends to meet its first cantus note in bar 3; this idea of a seamless segue is continued throughout the remaining three phrases.

In bar 4 we notice a brief chromatic ascent, recalling a similar passage in the Scheidt setting, in an otherwise freely devised line.

As we begin the third phrase, in bar 5, a three-step sequence is employed to allow for a moment of repose from the liberal flourishes that have typified the counterpoint thus far. This passage ultimately leads to the climax (about two-thirds through the piece) with a single high Bb quickly followed by a dramatic descent of parallel sixths that will bring us to the final phrase.

Since the first and last lines of Nun komm are identical, the free treble voice we composed in bars 1-2 can be converted into the free bass part in 7-8. This use of invertible counterpoint (wherein two or more contrapuntal voices are exchanged) brings closure to the piece by recapitulating opening material almost verbatim. A very brief codetta is added by extending the final note of the cantus and developing the last bass passage of bar 8 an octave lower.

Listen: Track 20

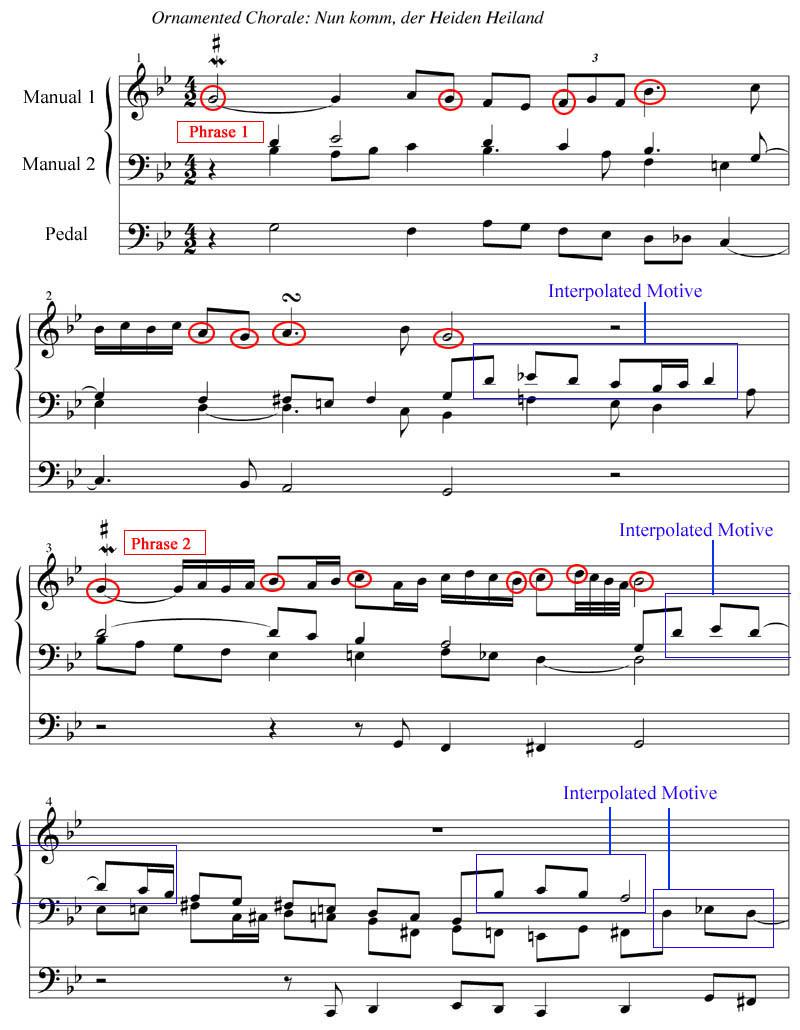

The ornamented chorale focuses first on crafting an elaborate and decorated version of the normally stately cantus. This finely detailed line can then be supported by an accompaniment comprised of material that is significantly less convoluted and restless. This form, which provides for enormous creative license, maintained a popularity throughout the Baroque. However, one can point to Franz Tunder (1614-67) as the North German composer to bring to the genre an expansiveness and creative depth that was unequalled during the era.

In our original composition below, we’ve chosen to expand the meter for the sake of clarity, especially at a slow tempo. The pitches from the original chorale melody are circled in red. Note the spacing between the notes is irregular and the contour of the solo is stretched both below and above its original ambitus (or range). The spacing between the phrases is irregular – only one beat is silent between the first and second phrases while an entire bar is wedged between the second and third. This approach is taken to avoid too monotonous a texture: gaps of varying lengths between phrases are created to allow the supporting voices to take some time to prepare for the next entrance with new material.

We have decided to build into the framework of the piece an interpolated motive (meaning a subsidiary and very brief melodic idea) that is occasionally introduced to bring greater unity to the somewhat meandering accompaniment.

The first and fourth phrases as set here are nearly identical, but to bring greater drama to the work, we have lifted the final cantus line an octave higher. To accomplish this change in register seamlessly, we have employed a rising scalar passage at the end of the third phrase in bar 5 to act as a segue. This ascent is balanced at the coda through a descending chain of suspensions in the accompaniment.

Listen: Track 21

The following listening list is provided for the student to explore numerous outstanding examples of how this form has been adapted from the late Renaissance to today.

List from the Common Practice

Johann Sebastian Bach: Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten [BWV 668] also known as Vor deinen Thron tret ich – excellent example of a canonic interpretation of a chorale.

Georg Böhm: Prelude “Vater unser im Himmelreich“ – one of the most outstanding examples of the ornamented chorale in the literature.

Johaness Brahms: Prelude “O Welt, ich muss dich lassen“

Dietrich Buxtehude: Partita “Auf meinen lieben Gott” – featuring settings in the form of dance movements.

Felix Mendelssohn: Organ Sonata VI – first movement is a set of variations on Vater unser im Himmelreich.

Max Reger: Fantasia “Alle Menschen müssen sterben“ – highly wrought, chromatic example of a chorale setting.

Samuel Scheidt: Tabulatura nova – an anthology assembled by the composer featuring a veritable encyclopedia of chorale and chant settings.

Johannes Schrem: Sancta Maria / Dies sind die heil’gen zehn Gebot‘ – one of the earliest trio settings from the Renaissance.

Ulrich Steigleder: Vater unser im Himmelreich – the most extensive partita of the Baroque era, comprised of forty settings.

Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck: O lux beata trinitas – a partita using a chant source.

List from the Modern Era

Hugo Distler: Kleine Orgelchoral-Bearbeitungen [Op. 8/III] – features neo-Renaissance techniques integrated with quartal/modal harmony.

Johann Nepomuk David: “Ich stürbe gern aus Minne“ – for soprano and organ

Flor Peeters: Prelude “Lasst uns erfreuen“ [Op. 81/2]

Hans Friedrich Micheelsen: Prelude “Erhalt uns, Herr, bei deinem Wort” – quartal harmony supporting the cantus.

Josef Ahrens: Das heilige Jahr – compendium of short compositions exploring a wide variety of textures and harmonic ideas.