10 Quartal Harmony

QUARTAL HARMONY

Many young composers are under the impression that since tertian harmony is based on thirds, that quartal harmony is a replacement, being based on fourths. However, in practice (and in the literature) it is more of an augmentation of the tertian vocabulary, not a substitution. Some of the first prominent composers to write pieces implementing quartal concepts, such as Hugo Distler, Arnold Schönberg, and Paul Hindemith, rarely simply stacked perfect fourths on top of one another (an exception would be Schönberg’s Chamber Symphony Op. 9 in the slow section). Instead, they re-examined the concepts of consonance vs. dissonance. If one rotates a series of stacked fourths over the tonic in C (C, F, and Bb) one notices that also inherent in the combination is the minor seventh/major second (C to Bb). As such, the intervals of the major second, perfect fourth, and minor seventh all can be considered consonances – intervals that no longer need resolution.

In addition, the use of a minor seventh over the tonic implies a flatted seventh scale degree in the key – a modal influence over a tonal one. The sharing of sonorities between the tertian and quartal harmonic realms carries over to the often ambivalent articulation of tonal and modal structures. Once again, rather than choosing one system over another, composers have taken a more inclusive approach, allowing for both languages to co-exist within the confines of a single work.

An approach often observed regarding voice leading in pieces that employ quartal harmony is the somewhat archaic use of parallel perfect intervals. Derived from one of the earliest forms of Western music, organum uses parallel fourths, fifths, and octaves to reinforce its modal melodies. Although disallowed in subsequent eras, this sonority only expands the modern composer’s palette if used judiciously.

Index

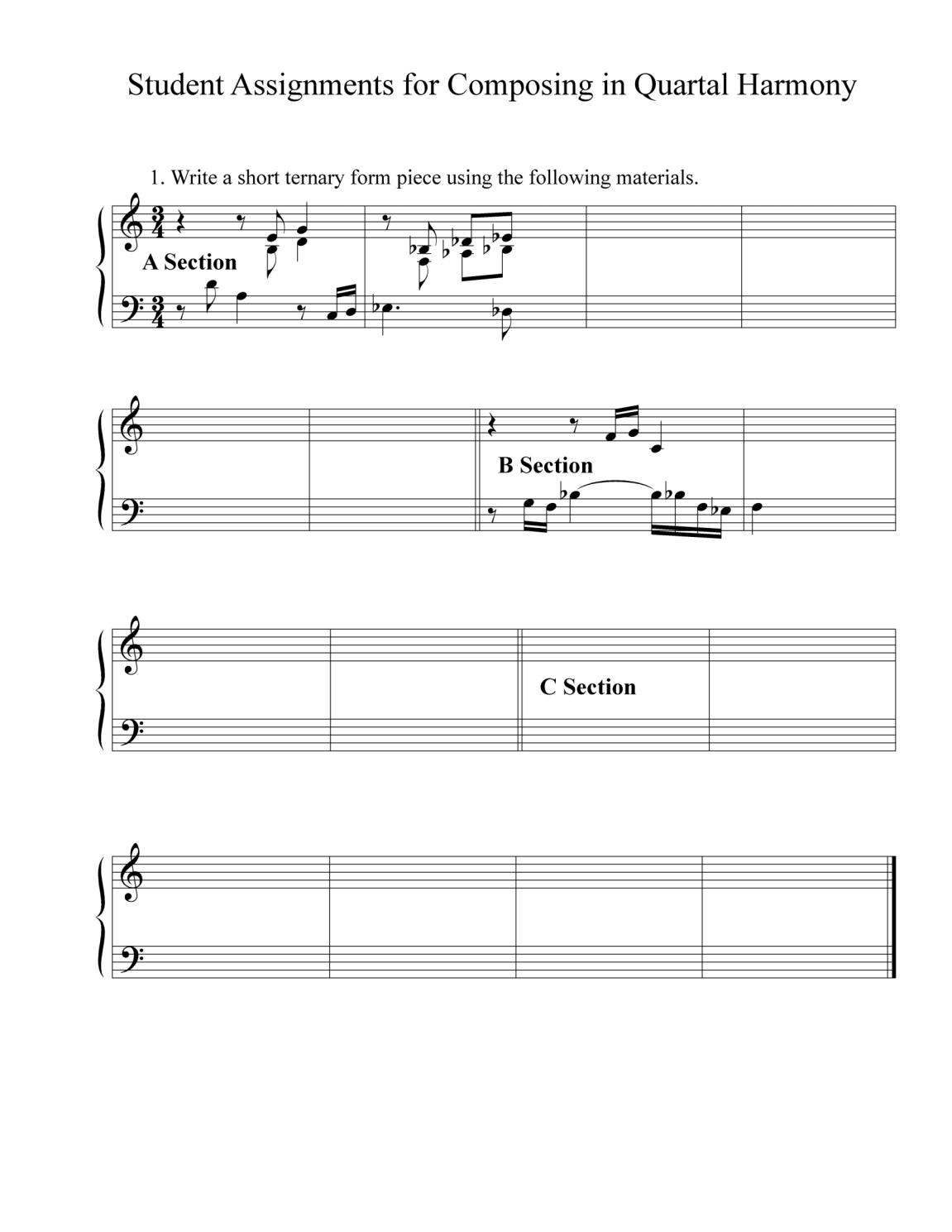

A. Ternary Piece using Quartal Harmony

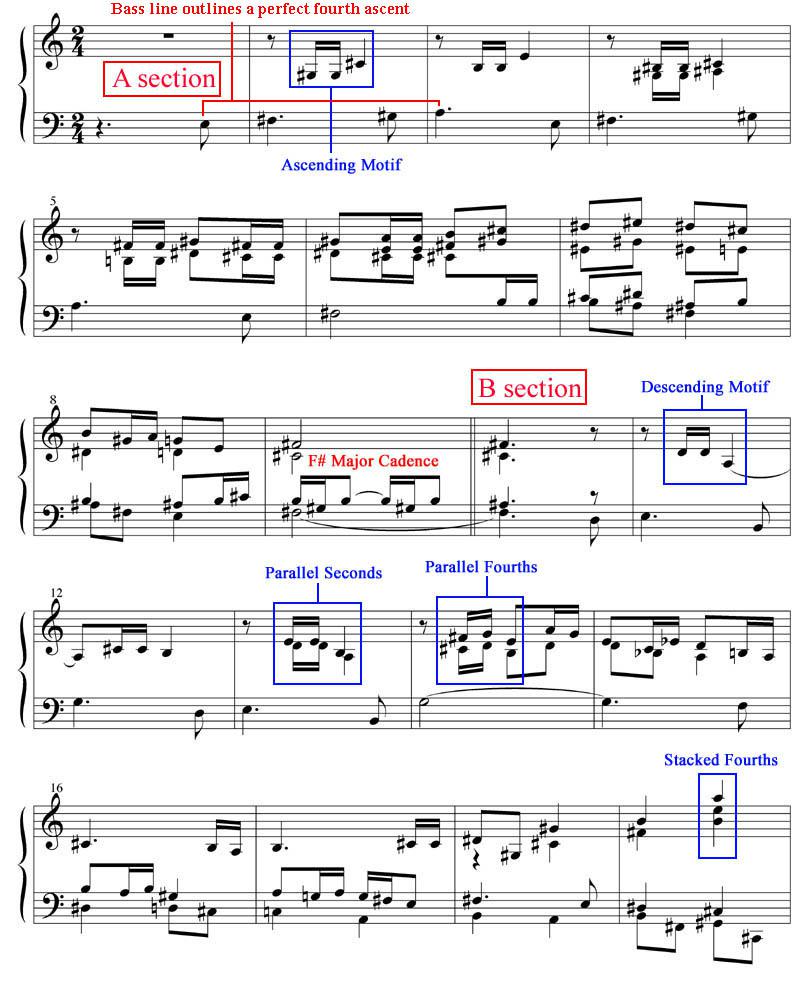

In the following example, we have adopted a structure already familiar to us from a previous lesson, the ternary form.

In the A section we have created a unified relationship between treble and bass within the quartal construct: the motive is distinguished by an ascending perfect fourth while the bass line outlines a perfect fourth ascent. The major second is also the interval at the point of entrance of the treble line. Note that tertian harmonies (as in bar four) are freely dispersed in the course of the music.

The relationship between the two sections is also in alignment with the traditional ternary form – however adapted here to suit the quartal construct. Note that B also acts as a developmental section, introducing an inverted motive, a more varied texture, and a climactic passage (bars 19-20).

Listen: Track 24

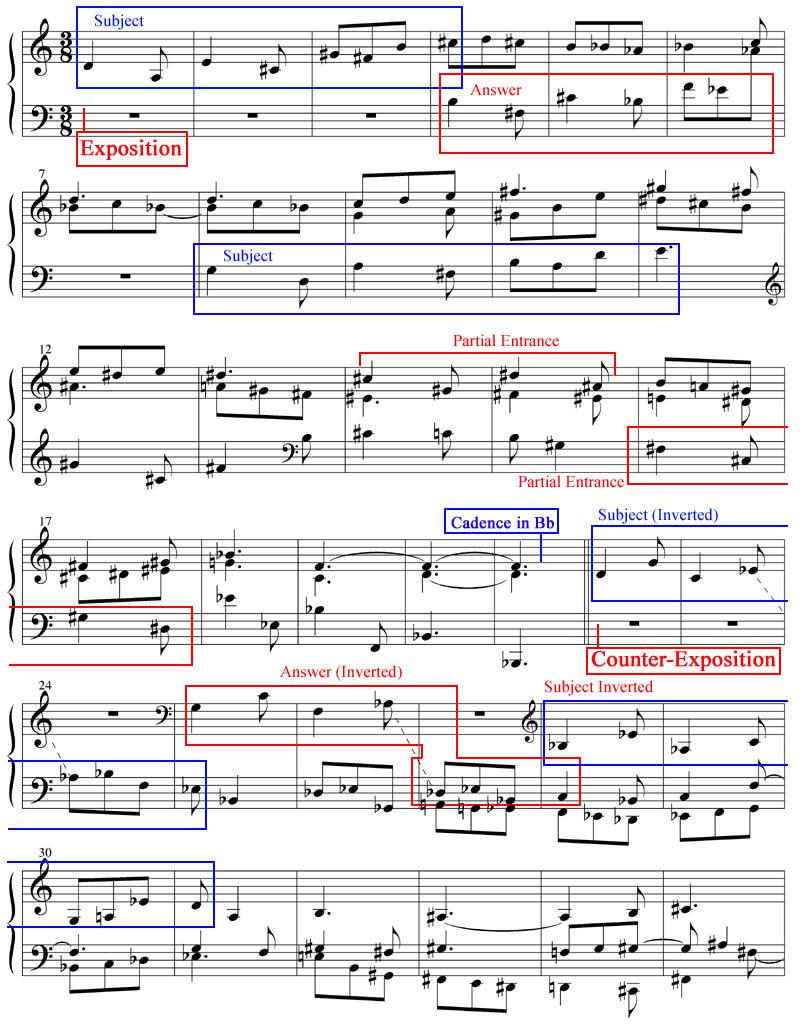

B. Quartal Harmony Fugue

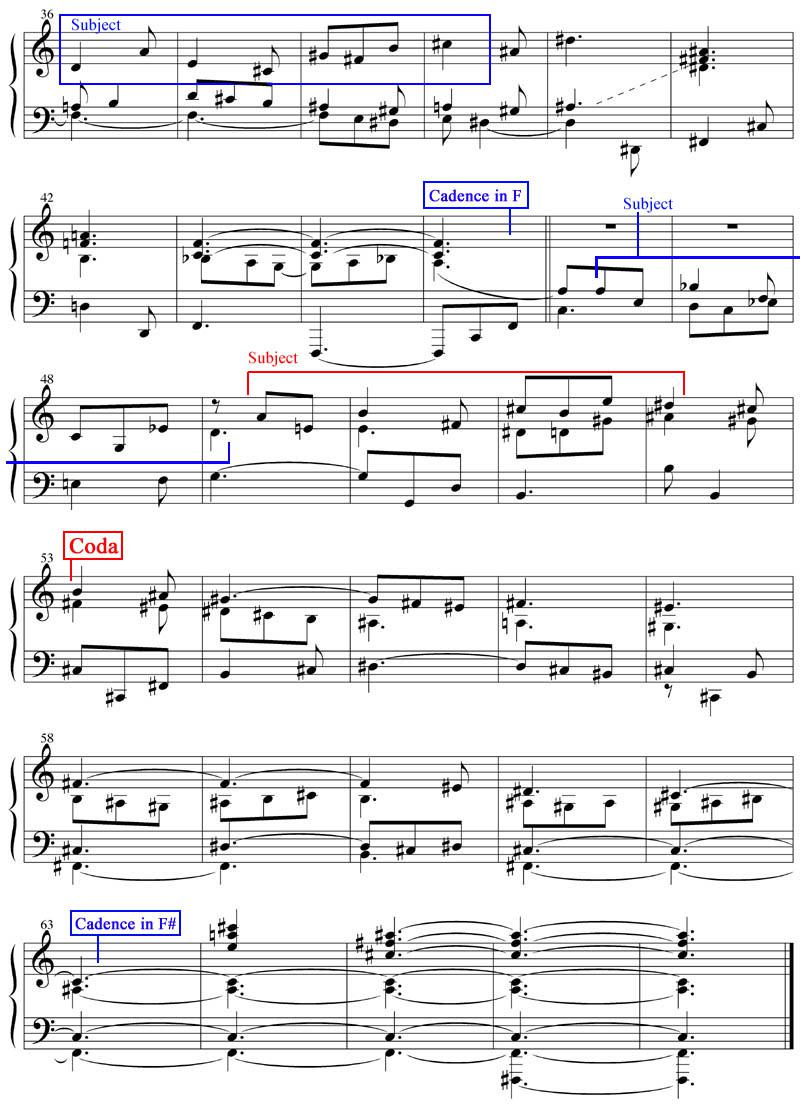

In the following example, we have adopted another form familiar to us from the previous lesson on the fugue.

Exposition. Although not necessary, we have molded our subject here to incorporate many of the significant intervals of the quartal system, namely the perfect fourth, fifth, and major second. However, unlike the Common Practice fugue, the transposition of our

answer is not restricted to the dominant key region. As well, the final entrance of the subject in the exposition is introduced in a key to our taste.

Counter-Exposition. In bar 22 a second exposition begins, this time with the subject inverted.

Key/Modal Regions and Cadence Points. As we have seen in the ternary example, and distinctly evident in this piece, the use of the quartal system allows for easily accomplished modulations, more so than in the tertian. A notational obstacle can occur, however, and the composer may sometimes have to jump from sharps to flats (or vice versa) to keep the diatonic relationships readable (see bars 17-18 below). As well, the composer can choose not to observe the tertian (Common Practice) necessity to return to the original key, especially since in the quartal system the key can be somewhat ambivalent from the outset. In our piece, for example, there are three cadence points: the first in Bb, the second in F, and the third in F#.

Listen: Track 25

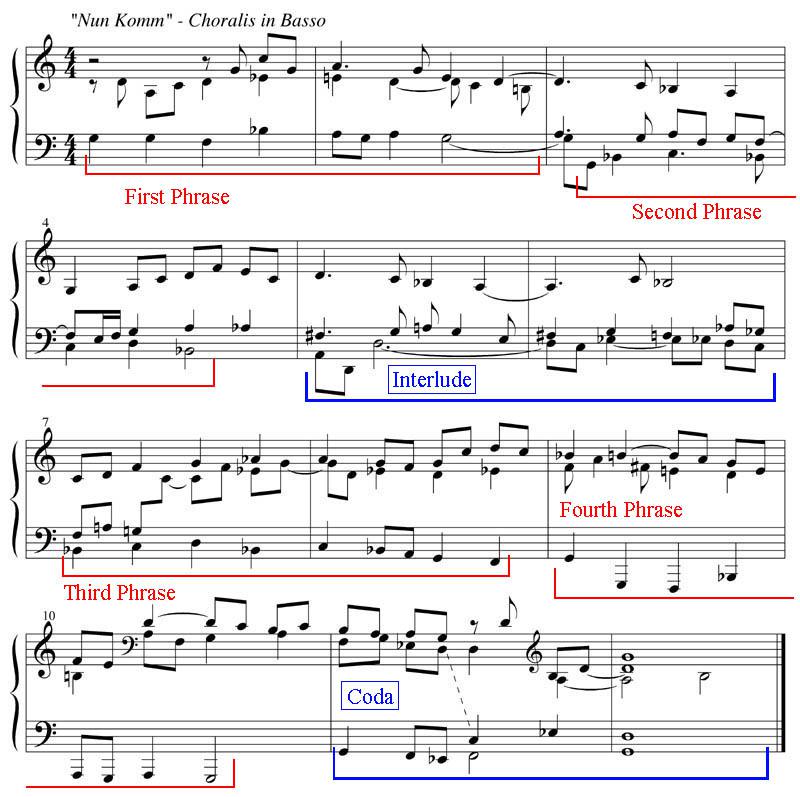

C. Chorale Setting using Quartal Harmony

In the following example, we will create a chorale setting based on the tune Nun komm that we explored in a previous chapter. Nun komm‘s modal character, as well as the major second and perfect fourth intervals that provide the distinct profile to the first phrase, makes this tune well suited to our quartal vocabulary.

Note that the two upper voices consist primarily of free counterpoint (meaning without imitation). Structurally we have introduced an interlude and coda that is seamlessly integrated within the course of the phrases.

Listen: Track 26