16 Process Music [Minimalism]

Process Music [Minimalism]

Although the term Minimalism has been widely adopted to describe the shared aesthetic principles of particular musicians (and artists), it fails to speak to any common methodology. We have, instead, chosen here to use the term process music, as this expression more accurately describes the compositional approach. Although composers who have implemented process music concepts have developed varied styles and techniques, the two fundamental concerns involve creating works consisting of extremely reduced basic materials that are developed through repetition and gradual modification.

Regarding the type of basic building blocks with which to begin a work, composers such as the American-born Frederic Rzewski (b. 1938) and Terry Riley (b. 1935) choose primarily diatonic material of a decidedly modal character, whereas others, such as Morton Feldman (1926-1987), favor chromatic, non-tonal ideas. Despite this, minimalism has come to be associated with compositions that adopt the former rather than the later stylistic premise.

Two ‘minimalist’ systems that have been used extensively are the additive process and the phasing process. The additive process involves an initial musical idea that expands and/or contracts over the course of a series of modifications. The building blocks are considered modular units that require repetition to clearly present its properties. Phasing processes are based on the concept of musical segments that shift against one another over a period of time as they are repeated. Note that the use of repetition in both cases is key for the listener’s cognitive facilities to ‘process’ the system involved, making this music more experiential in nature rather than expressive per se.

We will compose three works, each exploring one of the processes associated with this compositional system.

Index

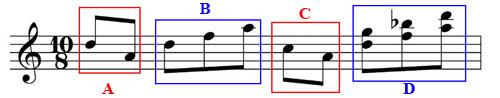

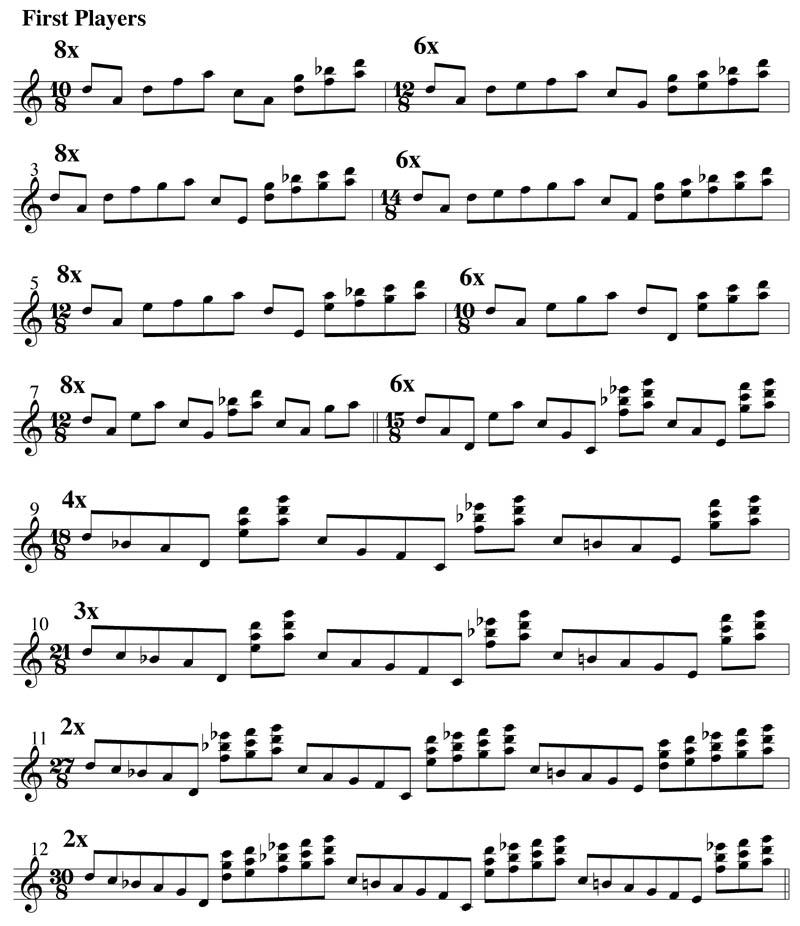

A. Additive Process

Developing the Basic Materials. We will begin with two simple ideas, descending and ascending patterns. Our material must be constructed so the listener can clearly distinguish the constituent parts while maintaining continuity between them. A and C are identical except for the first note of each group. B and D are as well identical with the exception of the splitting of D into parallel fourths. By repeating this modular unit we are providing the listener a durational parameter in order to allow modifications to be comprehended. If we moved directly from this bar to the next, the listener would have no guide as to what is primary material and what is development.

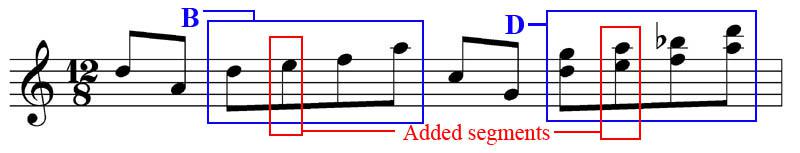

Preparing the Modifications. We need to take care with how we first modify the material, and the manner in which it is applied, in that this transformation will be the initial clue for the listener to understand the succeeding process. The continuity that has been established within the construction of the basic materials themselves should be reflected in a consistent manner of development through each modular unit. Here we have decided to leave A and C unchanged while B and D have added segments. Of course any additions or subtractions and their placement are at the discretion of the composer. The choice to put these additions within a musical construct rather than at the beginning or end was determined by their triadic nature – simply put, the idea is to ‘fill in’ the leaps.

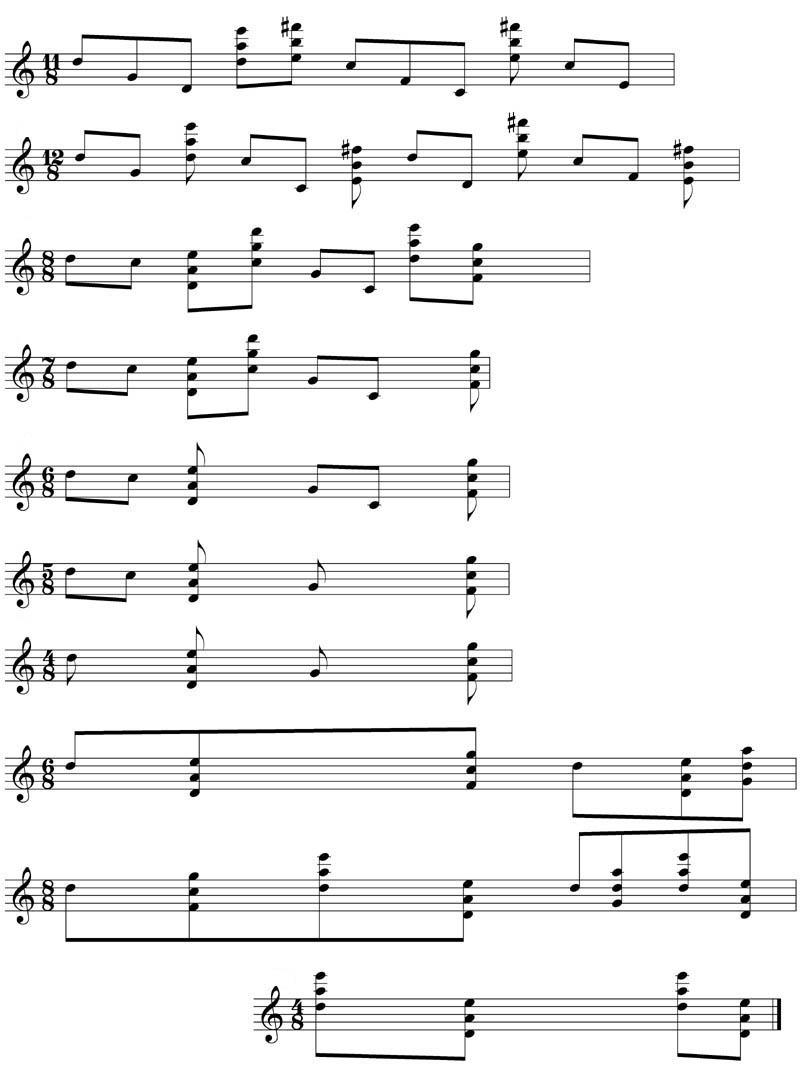

Note that the process from modular units 1-7 consists of B and D expanding and then contracting again. By 7 there is no durational difference between any of the musical segments.

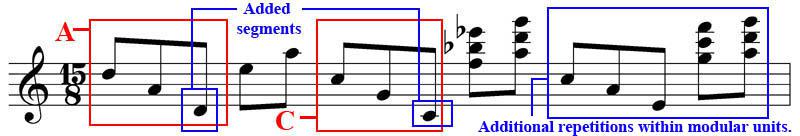

Different Modifications. The second section begins by extending the A and C motives first this time, before allowing B and D to join. To key the listener in to the fact that a new section has arrived, a new voice is introduced, again a parallel fourth higher in D.

Expansion and Contraction. The greatest point of extension occurs in modular unit 12, exactly halfway through our process. The addition of selected chromaticism during this middle section introduces another dimension for the listener to use in the cognitive process as the modular units become increasingly longer. As well, we will restrict the number of repetitions during these passages to avoid tiring the listener’s ear. It is important to note that it was a decision based on compositional dramatic interest to limit the expansion here; some process pieces involve expansion ad infinitum.

The next section transforms our initial material through subtracting segments in a different manner than when they were first added. To provide the listener with another clue that a significant new pattern is beginning, the parallel fourth voices have been amplified to parallel fifths.

The final modular units become more concentrated than even the initial musical ideas, as the chart below illustrates.

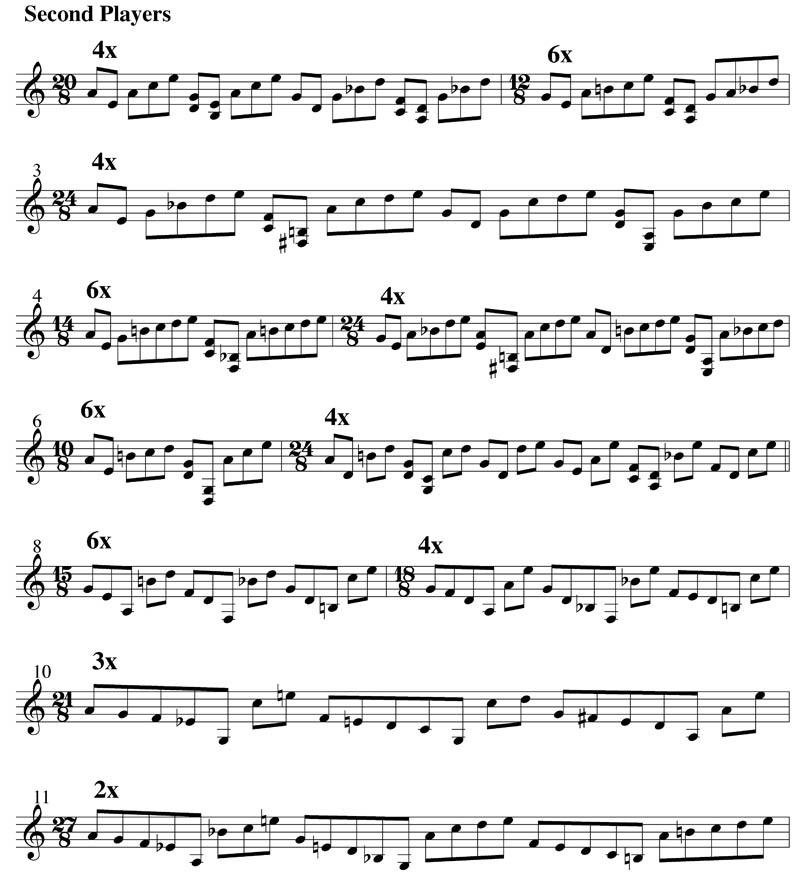

Subsidiary Parts. After writing the initial process, the composer noted that a compelling texture was lacking and a second part (or player) was composed. Since some of the measures here are of a different duration than in the first part, a full score is not possible. Compare the first modular unit below with our original: here we have applied the same pattern but with two different pitch interpretations. Therefore, the second part (in 20/8) must be repeated half as many times as the first part (in 10/8). As well, in keeping with the parallel fourth idea, we have created a second line a fourth lower than the original. In addition, instead of adding a parallel voice above in D (as in the original) in the second part C has an additional lower fourth.

Other Modifications. Again, to bring clarity to the structure, the addition of a second part is useful regarding texture and details. Note that in the second section, when the first part introduces a third, even higher voice, the lowest voice of the second part is dropped out. Only in the third section (modular units 13-24) is it brought back to fill out the final texture. As well, the pitch content of the second part is at times capricious in order to bring an unexpected element into the otherwise systematic rubric.

Regarding the number of repetitions, the length of the piece overall informs the individual decisions of the composer. However, to avoid too consistent an approach, an alternation of 8 and 6 repetitions in the shorter modular units provides enough time for the listener to grasp the content and follow the new rhythmic layout without saturating the ear. The numbers of repetitions of the longer modular units are kept at a minimum for the same reason.

Listen: Track 34 (ensemble – 1st Players: flute, clarinet, harp; 2nd Players: vibes, bass clarinet)

B. Phasing Process

Phasing with Equal Modular Units. The simplest form of the phasing process involves taking two identical modular units and shifting each element rhythmically forward or backward within one while the other remains unchanged. To illustrate the result, we have taken musical ideas similar to our last piece and applied this process. To elucidate the analysis, we have circled one element so that its changing position can be traced throughout the piece. The composition does not leave much room for compositional choice once the materials are chosen and the particular system is set in motion. However, the rhythmic patterns that emerge from the interplay between the voices can be intriguing.

This type of work also asks for the listener to apply the ear in unique ways since a traditional narrative is absent. Try to focus, for example, on only the low A’s and G’s throughout as you hear the piece unfold. What one also notices is that despite the fact that tonal/modal materials are used in this style, the concept of dissonance is suspended. The idea of tension relies more on the changing patterns of synchronization. In our performance below, each stage of the process is repeated four times.

Listen: Track 35 (harp and vibraphone arrangement)

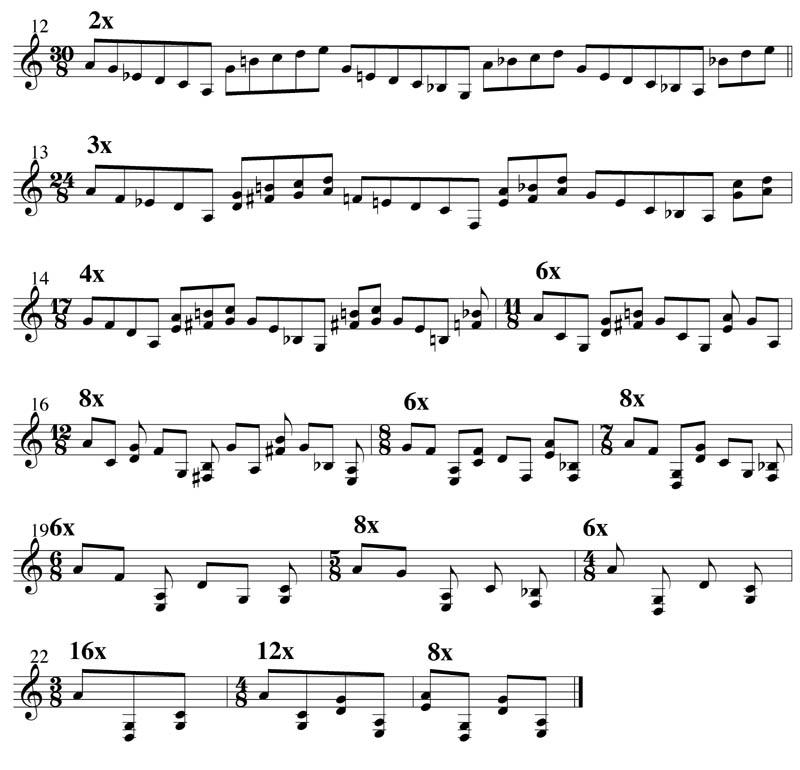

Phasing with Unequal Modular Units. When juxtaposing multiple modular units, each with their own duration, the resultant patterns can become that much more complex. Although the composer is, of course, at liberty to transform each individual part (similar to our previous two pieces), allowing them to play out without external modification can be aesthetically rewarding on its own.

In the following piece we have created five disparate patterns in A Dorian in which each modular unit possesses a unique duration. In our performance below, each pattern is introduced successively rather than simultaneously so that the listener can appreciate each design and its interplay with the existing voices before another enters. To conclude such a piece, we can allow each voice to repeat its pattern until all end together. However, because of the numerous voices and their asymmetrical individual durations, this would become very tiresome. Instead, we have improvised a closing wherein each player in sequence arrives at, and sustains, the tonic, after which a brief codetta is improvised.

Listen: Track 36 (ensemble: vibraphone, clarinet, piano, marimba, and harp)