12 Polytonality

Polytonality

Polytonality is a catchall theoretical term that can be applied to a multiplicity of musical concepts that need to be examined individually.

Composers such as the American Charles Ives (1874-1954) write works that consist of strata of primarily diatonic parts, just each in a different key. This juxtaposition of two or more keys (or modes) can be used in denser texture as a way to draw clear lines of delineation between significantly contrasting material. However, when the substance of the music is more unified, the implementation of varying keys can be used to create a unique blending of harmonies.

Alternatively, composers such as Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji (1892-1988), freely draw from a triadically based vocabulary that does not necessarily relate to any single tonality. These chords and scalar materials can sound in succession and/or simultaneously to create unique and expressive sonorities.

A more systematic technique, planing (which is often associated with the so-called Impressionistic School of composition) involves articulating a series of chords of identical quality but with different roots. Although the scale from which the basic melody is derived can lie within one tonality, the displacement resulting from the accompanying chord qualities, which by definition will contain chromaticism in direct conflict with the underlying key, will suppress the functionality associated with those scale degrees.

Index

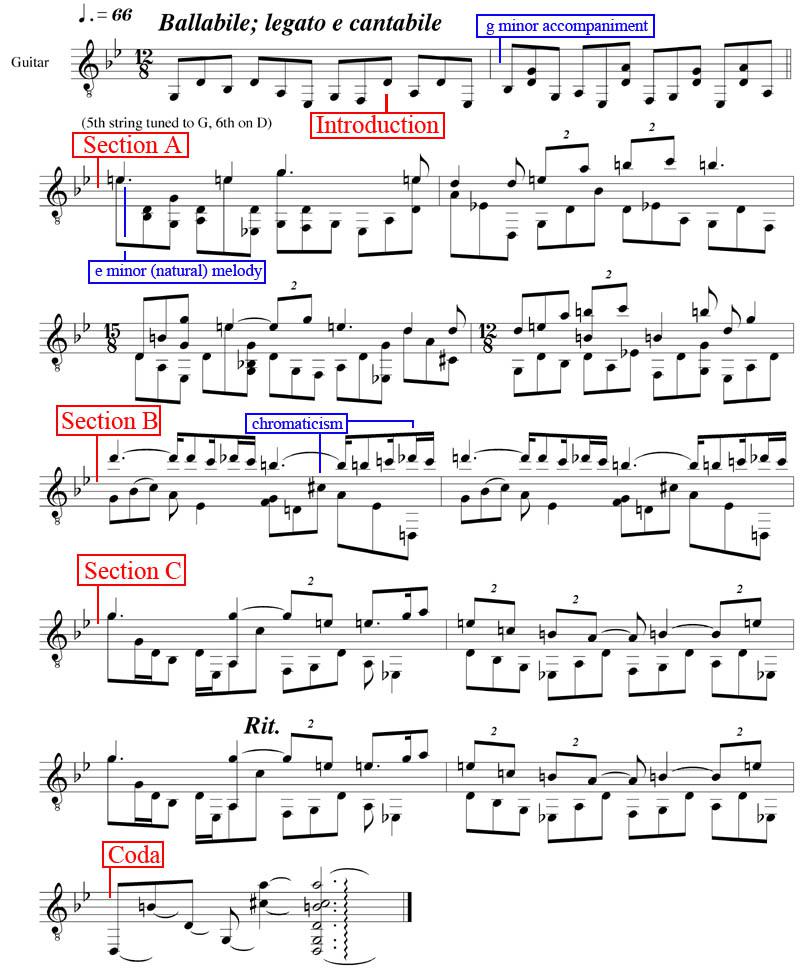

A. Bitonal Composition

Developing Compatible Keys in a Polytonal Composition. When working with two keys simultaneously, the composer must decide how they will complement one another (if they should, in fact) as well as how their characters will be exploited when in conjunction. In the following piece for guitar, we will establish two clearly distinct key regions: g minor and e minor. These keys can complement one another in that they share many pitches, however the critical third of g minor (Bb) will create tension with the dominant of e minor (B natural) and the tonic of e minor is in complete conflict with the sub-mediant of g minor (Eb).

To bring clarity to the situation, the keys will be separated first in terms of register, with g minor restricted to the lower tessitura, functioning as an accompaniment to the treble melody in e minor. Secondly, they will be expressed in contrasting rhythmic strata, with the triple time accompaniment guiding the meter in which the duple time melody will be articulated. In this way the metrical layout will be complementary similarly to the juxtaposition of the keys.

The piece is laid out in four distinct sections with a brief coda. The introduction establishes for the listener a simple accompanimental figuration unambiguously in g minor. This allows the contrast that is established with the sudden commencement of the melody in e minor in section A to be more significant.

Section B introduces some brief chromaticism into the two key regions, which is, ironically, the same sounding note (Db/C#) in each. As well, the climactic notes of the whole composition occur here.

Section C brings back the purely diatonic ideas of A but with the melody reaching into a lower register, thus bringing the two keys into their closest spacing.

The Coda finds a middle ground between the two keys, perhaps leaning a bit towards the accompaniment, in order to facilitate a persuasive sounding cadence. As well, the C# of the middle section is reasserted as a concluding bond.

Listen: Track 29

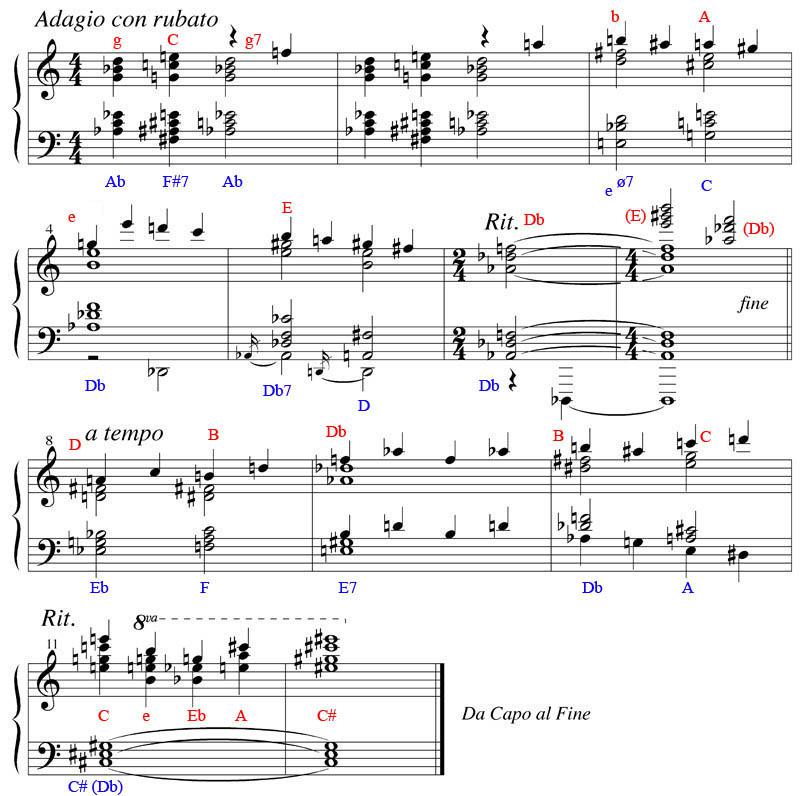

B. Polychordal Composition

Developing a Non-tonal Triadic Vocabulary. When juxtaposing two or more chordal structures from different keys, two fundamental issues come in to play: the degree of harmonic congruence between the triads and the manner in which the progression will take shape. To explore these topics, we have composed a brief, simple, and stately ternary piece for piano that will exhibit primarily contrasting tonal triads between the treble and bass throughout. The spelling of chords is largely dependent on how easily they can be read simultaneously rather than chronologically within each hand. As well, our analysis will not be concerned with inversion, only root and quality.

In the first bar, the treble contains a diatonic-root progression g-C-g(7). However, because the g is minor and the C is major, the idea that the progression is from either key is suppressed. In the bass, a step progression of a major second is constructed Ab-F#(Gb)-Ab. Regarding the overall harmonic tension, we observe the greatest degree of friction in the first juxtaposition since each note in the bass is contrasted by a semitone in the treble. The second sonority is built upon the disposition of a tritone, with the common E between the two chords.

In bar three, the first sonority exudes significantly less tension with the quasi-whole-tone construction of D-E-F#-(G#)-Bb. The second sonority is the first in the composition to feature a contrast based on a third A-C. The particular quality that results stems from the conflict between the A major quality (through the use of the C#) and its minor counterpart (C) in the lower triad. This third relation is explored throughout the piece (note the many Db-E based triads that are juxtaposed). By the end of the first section, the two hands converge on the same tonality.

The second part begins very much like the first with each hand displaced by a semitone followed by a tritone. It is interesting to compare the last sonority of bar 10 with the second of bar 3. Here the A-C (third relation) juxtaposition is employed once again, but this time reversing hands. Bar 11-12 is unique in that it pits one triad in the bass against a sequence of different triads (with different degrees of tension) in the treble.

On a final note, examine the treble part in bars 8-10. This can be construed as a type of planing, in which the progression is built upon a succession of triads with identical qualities.

Listen: Track 30