5 Composing Canons

Canons

Imitation has been, and continues to be, one of the driving forces behind many of the forms that distinguish the Western musical tradition. Of the many polyphonic structures built on the foundation of imitation between independent voices, the strictest is the canon (from the Greek kanon, meaning ‘rule’). Despite its apparent rigor, one of the advantages to this form is a straight-forward methodology involved in its composition. Canons have been used by composers as independent pieces, integral sections of larger works, or a starting point for less-constrained subsequent development. As such, the models below are intended to provide the student with a step-by-step approach to writing their own pieces using this fundamental compositional tool using the vocabulary of the Common Practice.

Index

A. Simple two-part canon at the octave

B. Simple two-part canon at intervals other than the octave

C. Two-part inversion canon at the octave

D. Two-part augmentation canon at the octave

A. Simple two-part canon at the octave

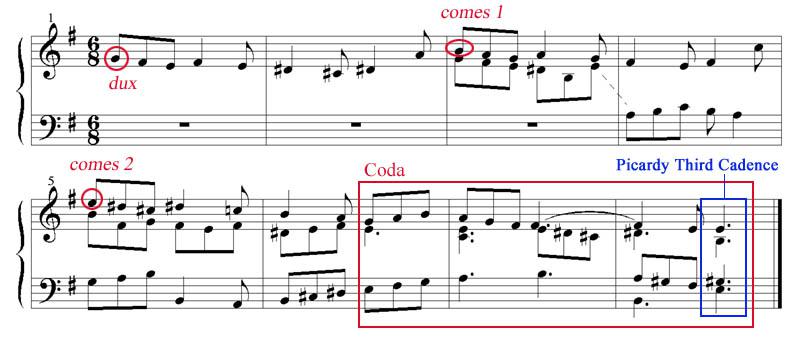

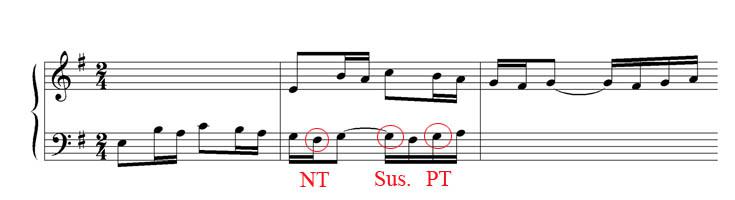

The first step involves creating a single melodic line that is both brief and has a distinct musical profile. The later can be accomplished through the careful placement of a large leap and a single climax note within the course of the motivic design. This voice is known as the dux, which is Latin for ‘leader’. The dux will establish what the following voice, or comes (Latin for ‘companion’), will imitate. Note that even when composing for a solo voice, the correct use of non-harmonic tones is pertinent in understanding what pitches will support a triad within a progression. As well, establishing a clear harmonic rhythm from the outset is useful once the second voice enters. In the following example, it is clear that the e minor tonality is established in the dux through a melody that outlines the progression of i-iv, wherein the harmonic rhythm is quarter-quarter. As well, we have provided a strong rhythmic impulse through the alternation of eighths and paired sixteenths.

Next, the composer simply copies the dux material in the following bar an octave higher: this is the entrance of the comes.

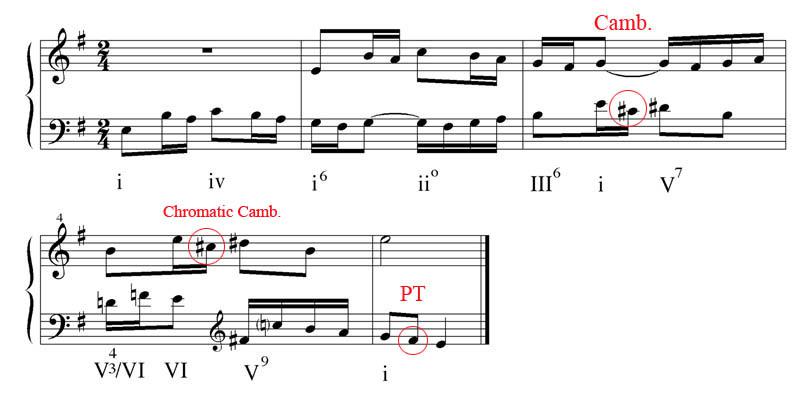

Now the composer can introduce new material in the dux which complements the comes part above. We must be careful to employ consonances (primarily 6ths and 3rds) to generate triadic implications between the two voices. Equally important is the rhythmic interplay and continuity: as the sixteenth-note motive has been established in bar one, this impulse should be maintained to a fair degree in the subsequent development of the piece (with the possible exception of cadence regions). As well, leaps in one voice can be balanced with more scale-based material in the other. In all, when composing new material in the dux, it must maintain its own individual melodic contour. To test this, play the new line alone and judge whether or not it still sounds like an independent melody. Another way to test the balance between the melodic contours of the voices is locating all regions of similar, parallel, contrary, and oblique motion between the voices – none should dominate in the course of a phrase and none should be entirely excluded either.

As in step two, we now copy this accompanying material from the dux to the comes in the next bar – this pattern will be maintained until the arrival of the cadence.

Finally, at the cadence point, the composer can chose to make some alterations within the comes – the composer should support the tonal function of the end of the phrase rather than necessarily feel compelled to copy the dux verbatim. Note that at all times the composer must be aware of the harmonic implications resulting from the interplay between the parts so that the progression proceeds logically.

Listen: Track 7

B. Simple two-part canon at intervals other than the octave

Once the student has successfully composed a simple canon at the octave, other techniques can be explored. One such technique involves composing a canon at an interval other than the octave. In the following example, a canon at the fifth is illustrated using the same initial melody as the previous piece. Remember, the procedure is the same in writing all canons of this nature. Note that once the composer chooses to write a canon at any interval other than the octave (or unison), minor adjustments can be made in the pitch content of the comes in order to more appropriately agree with the overall tonality or a specific tonal region. In bar three we notice that the D in the treble part has been raised to a D# – although it is imitating the G from bar two in the bass, it is chromatically altered here to imply the major dominant (V) with the dux below. Similarly, the chromatically raised seventh and sixth scale degrees in the dux at the end of bar two are not raised in the following bar in the comes: doing so may imply a tonal shift towards b minor (which is entirely plausible, but not advisable in such a brief example as this – the student may wish to explore canonic modulation further in the study of the genre).

Listen: Track 8

The following two examples are intended as additional illustrations of simple two part canons. In the first, we have another canon at the octave with the dux in the bass part followed by the comes a bar later. Note that these canons exemplify a significant High Baroque tendency to alternate and interlock the rhythmic activity between the constituent voice parts in order to sustain a state of near-perpetual motion.

Listen: Track 9

In the second, a canon at the sixth, we have reversed the order of the entrances, with the treble acting as the dux. As can be observed in this brief piece, an interesting texture results from the crossing of the dux and the comes, a technique that the student is encouraged to explore.

Listen: Track 10

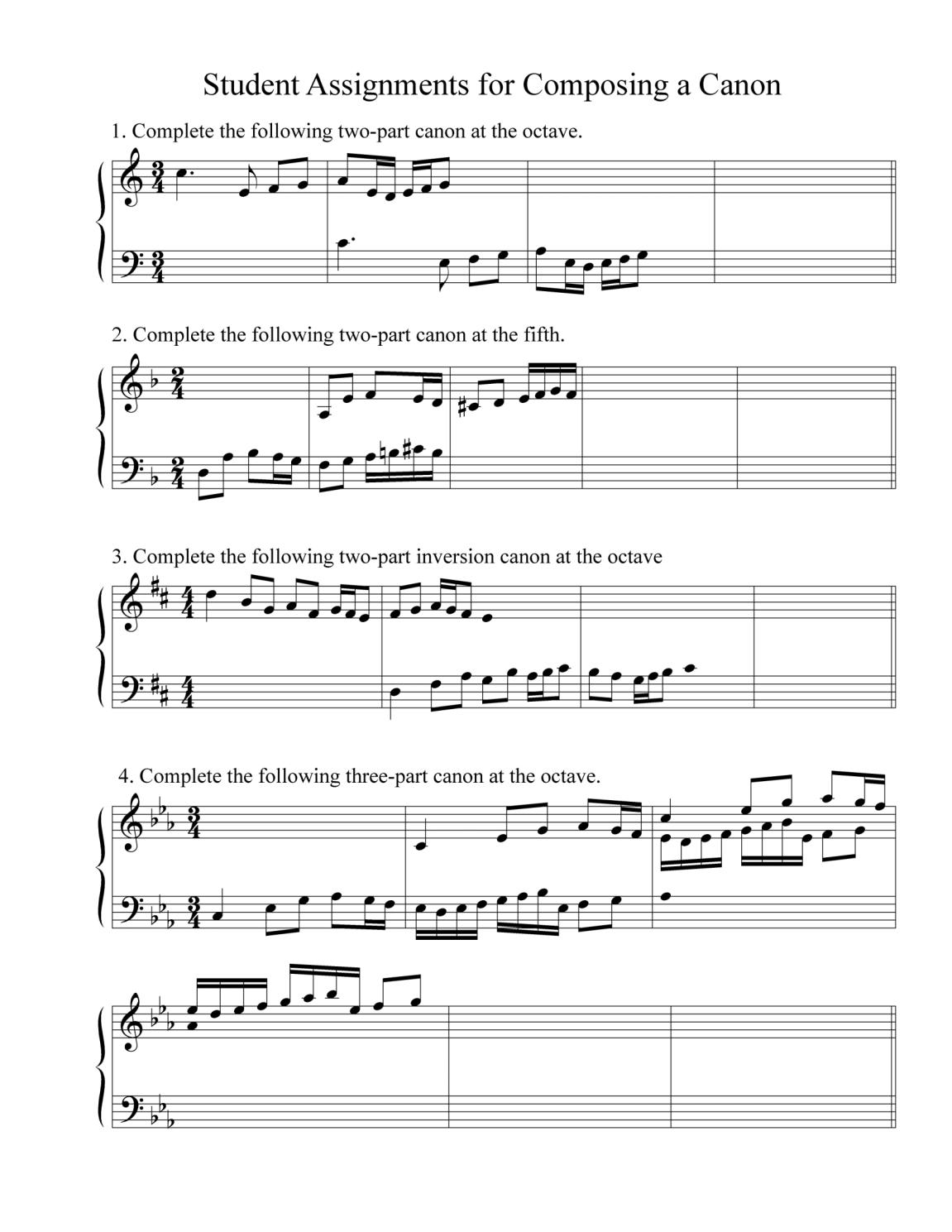

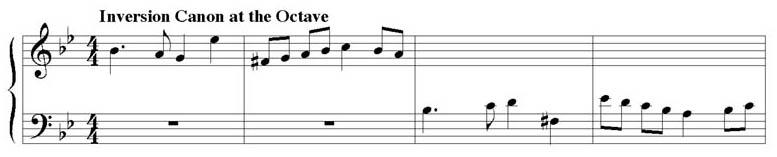

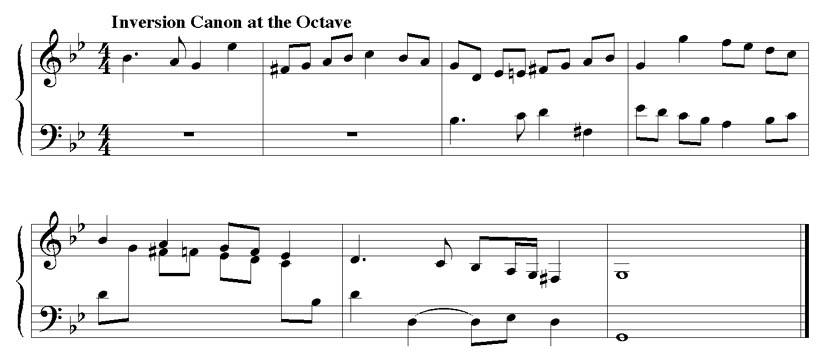

C. Two-part inversion canon at the octave

One of the basic manipulations of melodic material that can be implemented in order to achieve a new and distinct contour is the inversion. As we have seen before, it is sometimes necessary to make chromatic and other minor alterations in order for the new line to conform to the tonal space it has been accorded. However, as with the previous canons, the approach to its composition is not all that different. In step one, we have provided the two bar introduction of the dux material (treble voice) followed by its inversion in the comes (bass voice).

Next, we continue to compose as previously described. In this example note the climax occurs at the octave leap in bar four (dux), which becomes the dominant in the penultimate bar (comes).

Listen: Track 11

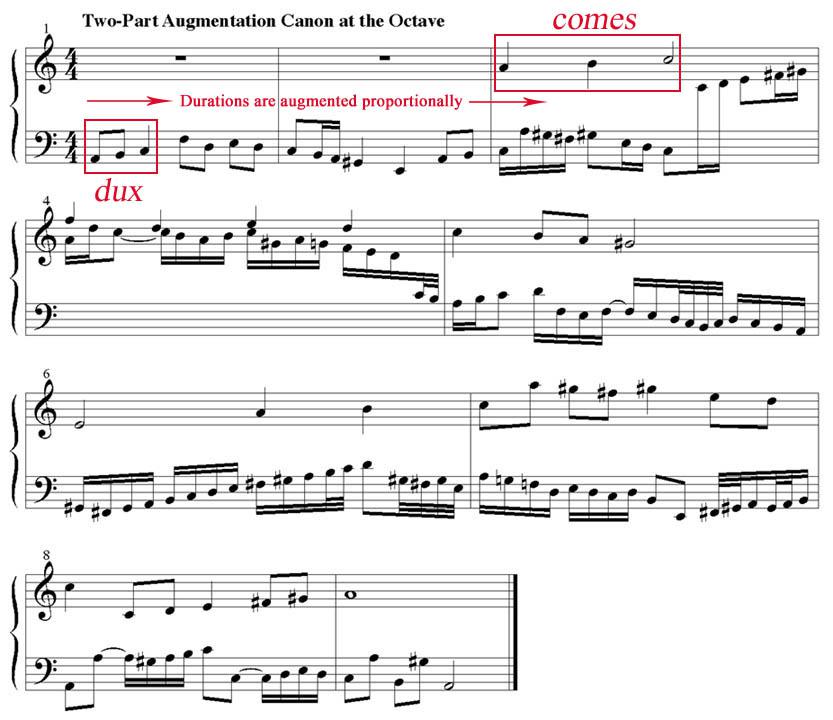

D. Two-part augmentation canon at the octave

Although used less often, another transformation that supplies the composer with a unique approach to canonic composition is rhythmic augmentation. In its simplest form, the durations of the dux are increasing proportionally in the comes. Unlike our previous canonic works, this change in the basic impulse creates an opportunity for the composer to explore a dux contrapuntal line with more fantasy and activity, both in terms of range and decorative aspects.

Listen: Track 12

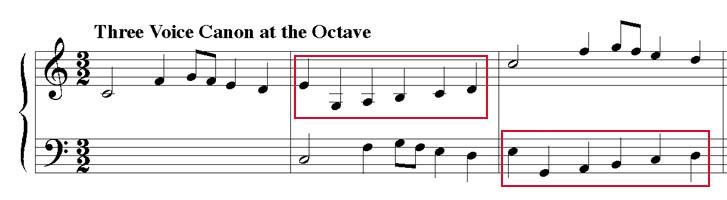

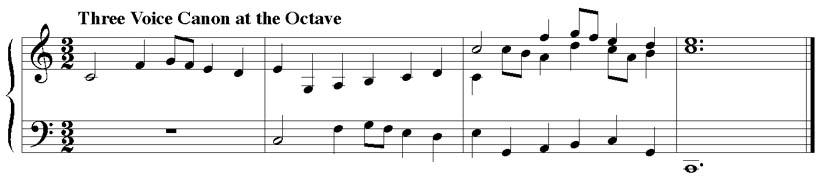

E. Simple three-part canon at the octave

In a three-part canon, the composer must contend with two comes voices. So although the method of first creating the dux and then simply copying out the appropriate music in the following part, this must now be done twice. This also gives the composer additional choices regarding the order of the entries and in which voices the comes will occur. In this example, we have chosen to introduce the dux in the alto, followed by the comes 1 in the bass and the comes 2 in the soprano.

Similarly, when we compose a new contrapuntal line in the dux to complement the comes 1, it must be copied to the comes 1 to complement the comes 2.

Finally, we must compose a new dux line that both supports the overall harmonic implications and complements the two comes voices yet maintains a melodic integrity of its own. Don’t be surprised if this task seems to be the most difficult part of the composition. It is wise to remember that a strong melody doesn’t presuppose linear activity only – as we see in this example, the dux is comprised mostly of leaps in bar three, however it avoids sounding like an accompaniment and reveals a distinct and independent melodic profile of is own.

Listen: Track 13

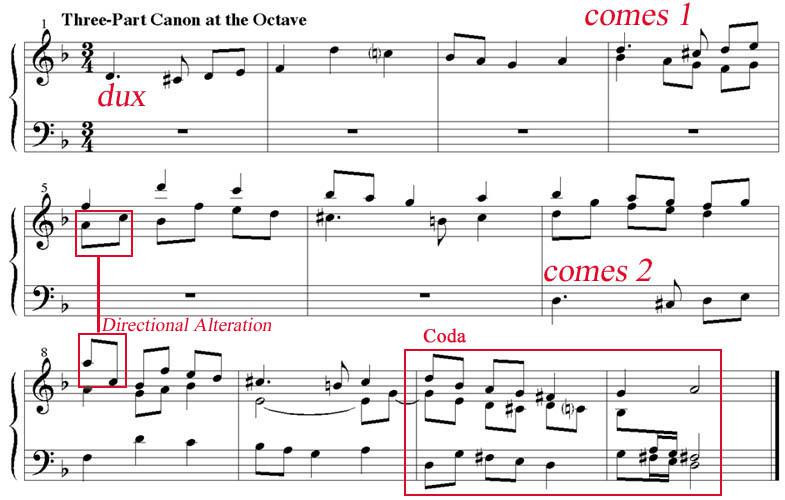

The following example is an additional illustration of a simple three-part canon. Of special interest here was the compositional choice to change the direction of one the leaps while maintaining integrity in terms of pitch. Although this was done to accommodate the two hands of a keyboardist (for which this piece was initially conceived), it also serves to keep the ranges of the constituent voices closer so that the counterpoint can be heard more properly. As well, a Coda is added to prolong the cadence region – note that the independence of the voices is compromised here to create for the listener a clear sign that the conclusion of the piece has arrived.

Listen: Track 14

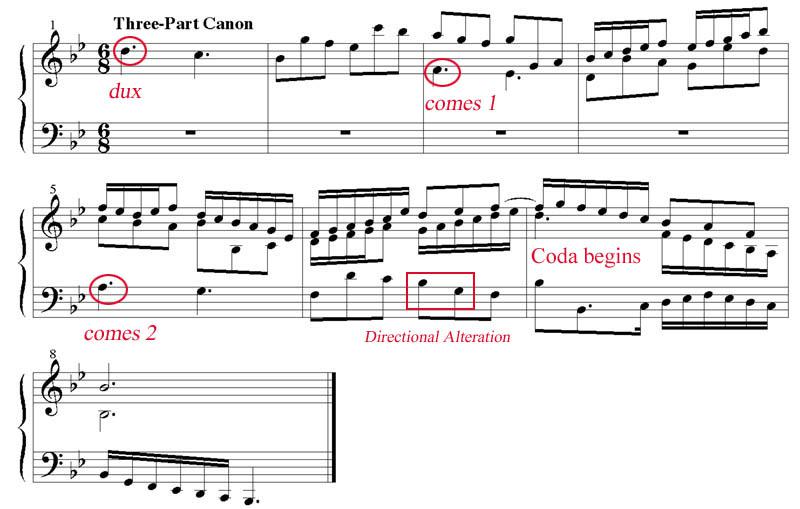

F. Three-part canon at intervals other than the octave

When dealing with multiple entrances at intervals other than the octave, the composer needs to choose an approach that will allow the counterpoint between the dux and the comes 1 also harmonize correctly between the comes 1 and comes 2. In the first example this is accomplished by having each voice entering at the same interval away from its predecessor.

To create more momentum in this exercise, sixteenth-note motives were employed as a counterpoint against the eighth-note subject.

Listen: Track 15

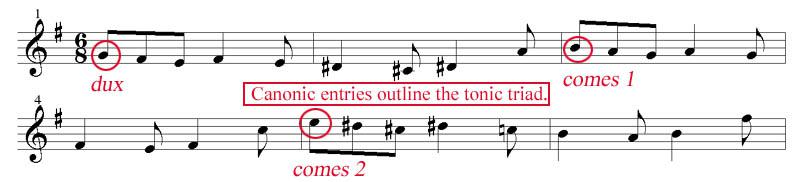

In the following example, each step of the tonic triad (e minor in this case) is articulated as the entry point for each of the three voices. Note that in regards to the sixth and seventh scale degree, there is some freedom regarding what pitch will be used (normally dependent upon the supporting harmonic structure).

As well, in this coda, the voice structure is expanded to four and a Picardy third cadence is implemented. The student should exert a sense of freedom in the coda sections of canons lest a strict canon be warranted.

Listen: Track 16