We will look at ways in which changing mapping technology has become embedded in daily life. With the development of location-aware technology like smartphones, there has been a big shift in what is possible to measure, who is collecting data, and how much data is produced. We will examine how geographic data, produced by diverse groups of people, have been incorporated into scientific research, disaster relief, and local government services. We will consider changes to mapmaking that have been made possible through the rise of online user-friendly geospatial tools and easier access to data. Relatedly, we will think about the digital divide between those who have access to mapping technology and those who do not. We will close the chapter by thinking about how technological change shapes the way we navigate between places and find information about businesses and services.

This chapter will introduce you to:

- Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI)

- Democratization of data production and mapping

- Participatory mapping

- Digital divides

- Issues around e-waste

- Counter-mapping

- Various ways maps are used in the real world

9.1 Volunteered Information

You may remember from your learning that spatial data has historically been collected by a few experts working for well-funded organizations (government, academia, etc.) and then made available to the public for use through static maps. Until recently, identifying the physical location of objects required special training and equipment. Technological developments in the mid-2000s, however, brought about huge changes in who collects data, how it is collected, and what types of places and events have data collected about them. Rather than a one-way exchange of information, it is now possible to produce spatial data using inexpensive, widely available mobile devices that accurately record spatial location without extensive training.

This form of data, collected by individuals with diverse backgrounds and skill levels, is known as Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI). VGI makes it possible to map phenomena that take place over such a large area or short period that they cannot be recorded by conventional data practices. VGI also supports groups that can map aspects of daily life ignored by official agencies. Data collected from cell phones can be used for surveillance, but the examples in this chapter will focus on the more positive and transparent uses of these new technologies. We will look at three different ways that VGI is being incorporated into daily practice, such as for science, disaster relief efforts, and local government.

9.1.1 VGI for Science

VGI offers exciting possibilities for scientific research. When collecting information about how a phenomenon occurs over space (e.g., the migration of birds from high to low latitudes in winter), scientists often have a limited number of monitoring sites they can support with trained staff and funding. Scientists increasingly use spatial data volunteered by enthusiastic citizens to expand what they can observe. It should be noted that citizen science projects were popular long before cell phones, but new technologies have increased the number of projects, the spatial accuracy of reported observations, and the ease of participation. With VGI, data can be collected and processed rapidly and at a very low cost. There are trade-offs, however, in terms of data quality. Even with the most well-intentioned volunteers, it can be difficult to establish consistent practices, coordinate data collection for all areas of interest, or assess possible errors in the data. In some cases, the volunteers are the sensors – they make observations and report back what they have seen or measured. For example, with eBird, volunteers count the number and type of birds they observe, as below. They enter the information into a website with reports from other birdwatchers. When combined, the data give a picture of species density and migration patterns.

Citizen science mapping. Ebird creates maps of bird distribution as reported by volunteer bird watchers on the site.

In other cases, information has already been collected but volunteers assist scientists in going through large quantities of data to identify important patterns. With Seafloor Explorer, for example, volunteers mark the number and type of species they observe in photographs of the seafloor. The location of each photo is known, helping scientists understand spatial patterns in marine biology.

Crowdsourced discovery. Volunteers mark sea star locations in an image from Seafloor Explorer. These locations can then be used by scientists to better track and understand the sea stars.

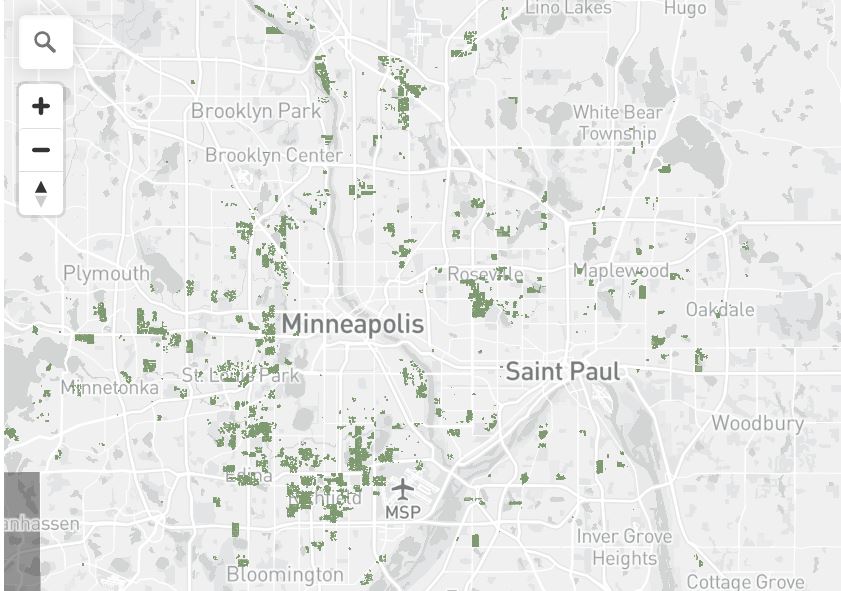

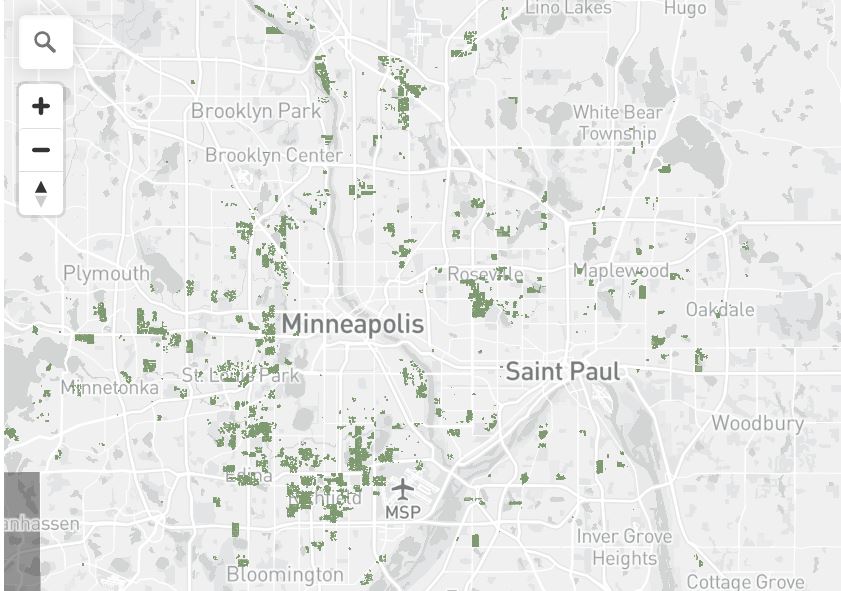

Social scientists are also relying on volunteer support for their mapping projects. Librarians, geographers, and other researchers with the Mapping Prejudice Project at the University of Minnesota have worked with thousands of volunteers to map historic racial covenants, or racially restrictive housing deeds, in Hennepin and Ramsey Counties. Volunteers help comb through tens of thousands of historic property deeds and locate phrases including language that explicitly restricted people who were not white from owning or occupying the property. After volunteers transcribe photographs of property records, researchers map the clean, verified data. The resulting maps have helped shed light on the historic nature of structural racism in a state with some of the largest racial disparities across the US.

Mapping Prejudice Project. Map of racial covenants in the Twin Cities of MN. Mapping Prejudice identifies and maps racial covenants, clauses that were inserted into property deeds to keep people who were not white from buying or occupying homes.

9.1.2 VGI for Disaster Response

When a disaster strikes, getting good information quickly is essential. By using data created by affected populations, emergency aid workers can get a better understanding of what is happening on the ground and respond appropriately. In January 2010, a massive earthquake shook Port-au-Prince, Haiti, claiming many lives and causing major damage to buildings.

Disaster. A United Nations patrol through the damaged suburb of Bel Air, Haiti (Jan 19 2010).

In the days following, many VGI and crowdsourcing endeavors emerged to support the relief effort. The group Mission 4636 set up a free number to which individuals could send text messages (SMS) to request supplies or report conditions such as people trapped beneath rubble, infrastructure damage, and food and water shortages. The site CrowdFlower coordinated Creole and French-speaking volunteers to translate, categorize, and geolocate over 40,000 received messages. A group of students at Tufts University used a mapping platform known as Ushahidi to sort through the massive influx of incoming data to identify urgent requests, as seen below. They also combined the translated messages with information from official reports and social media to be marked as events on a crisis map.

Crisis mapping. The Ushahidi crisis map for Haiti, built by volunteers and people sending information from the site of the disaster.

Texts and their crowdsourced translations were vital in responding to urgent medical and rescue requests. The geographic and linguistic knowledge of the crowd often far exceeded the resources available to UN and US responders. In cases of aggregate need, such as food and water shortages, however, the messages were less helpful. Emergency response officials did not trust that the incoming requests showed a complete picture of need, in part because people had to use cell phones to report information, and there may have been areas where people did not have phones.

One very useful VGI activity during the Haiti relief effort came from contributions to Open Street Map (OSM). OSM is an open-source map on which anyone can add or edit geographic data. At the time the earthquake hit, existing maps of Haiti were out of date and incomplete. Volunteers from all over the world worked to trace roads and buildings from high-resolution satellite imagery. Within a few days, the crowdsourced map was the most detailed available, as seen below. The United Nations, the World Bank, and search-and-rescue teams quickly adopted it for their work. Crisis maps and OSM have been used during other natural disasters, and mapping projects are also being done in areas likely to have severe weather or geologic events.

Open street map. The Open Street Map Port-au-Prince before and after the earthquake in Haiti shows how quickly volunteers can create new data and maps.

There is increasing recognition in the VGI world that what gets mapped depends significantly on who is doing the mapping. Organizations like OSM and Missing Maps know that having more female contributors, for example, means that more childcare centers, health clinics (especially relating to reproductive health), schools, safety-related locations, and even grocery stores will end up on the map. For this reason, VGI projects are increasingly seeking out women directly as mapmaker recruits.

9.1.3 VGI for Government

Many local governments are using VGI to monitor traffic patterns, plan new bike routes, and interact with citizens. One example of this move towards using ordinary people’s observations to improve urban spaces is SeeClickFix. Using this application, individuals can report issues they see around their neighborhood, such as street light malfunctions, graffiti, or abandoned vehicles, per the figure below. You can select the location of the issue you are reporting, and it will appear on a map with concerns posted by other users. City officials monitor these posts and pass the reports to road maintenance, police, or another relevant government department. You can also post photos of problems and signal support for issues reported by other people. In some ways, these systems are more transparent than calling a city to file a complaint – everyone can see the unresolved cases on the map. This can be a problem for city staff, though, if they are unable to respond quickly or if the person submitting the request is not satisfied with the fix.

Mobile government. The 311 Mobile Application interface for SeeClickFix in Minneapolis, MN, and a report submitted to SeeClickFix from a cell phone. Individuals are able to report issues they see around their neighborhood, such as street light malfunctions, graffiti, or abandoned vehicles.

9.2 Neogeography

In addition to expanding the number of people who can create data, shifts in technology have also made it easier to make maps without special training. There are several user-friendly online and open-source mapping tools, and many government and nonprofit organizations that make their data freely available. This trend has been described as a democratization of mapping practice since the public is actively encouraged to participate in describing the world.

Advocates for this new geography or neogeography argue that it takes the power to choose how the world is represented out of the hands of the military, government, and academics. Amateur and self-trained neogeographers combine already-existing online tools and data to share information with friends or create a useful synthesis tool. For example, they might use Google Maps to ‘mash-up’ data from several sources, make a story map of a recent vacation using geotagged photos and social media posts, or map the movements of famous fictional characters, as below. By putting data and mapping tools into a more diverse set of hands, a wider range of experiences and concerns become visible.

Neogeography. A Google Map made by a neogeographer that marks events and places described in John Steinbeck’s classic novel The Grapes of Wrath.

Some traditionally trained geographers and cartographers have questioned the quality or accuracy of the resulting maps. This book has spent dozens of pages discussing mapping principles and has only skimmed the surface of cartographic methods. With today’s technology, anyone can make a map, but they may not understand the underlying data, appropriate symbolization choices, or how to handle the ‘lies’ maps inevitably tell.

9.3 Participatory Mapping

Participatory mapping joins VGI and neogeography to create opportunities to decentralize the power of traditional institutions in mapping. VGI provides novel sources of data not curated by organizations like the US Census or private firms. In the case of neogeography, increasingly user-friendly tools allow individuals and groups to create maps without formal geographical training. A third way of opening the process of geospatial research is participatory mapping, where the lines between researcher and subject are blurred in ways that bring non-expert users into the mapping process.

Much conventional academic research follows a model that draws clear lines between researchers and research subjects. For example, a researcher studying vulnerability to flooding in a coastal community might collect data on topography, housing structures, and weather patterns to create a risk map for local officials without consulting residents in vulnerable areas. To give another example, the National Land Cover Database (NLCD) below, created by the US Geological Survey, uses remotely sensed imagery to make maps of multiple types of land uses by using predetermined categories such as Barren Land or Mixed Forest. In both cases, researchers are studying people and landscapes from a distance.

NLCD data. Map showing land use classification in the National Land Cover Database, 2021.

Participatory mapping blurs the line between researcher and research subject. Participatory mapping, often called public participatory GIS (PPGIS) or participatory GIS (PGIS), draws from work in related areas such as participatory action research. Such methods actively involve impacted communities, arguing that their perspectives and local expertise are essential to the research process. In addition, the inclusion of local groups from the beginning ensures that these individuals will have a say in how the research is conducted and can use the results of their research to advocate for desired changes. We know that mapping is a fusion of society and technology, and participatory mapping helps ensure that the ‘society’ component better reflects the broad range of people and institutions that govern social interactions.

One example of participatory mapping is a project done by Paul Robbins and others in Rajasthan, India (Robbins 2003). Officials in this area used geographic data to develop forest management plans, using categories very similar to the NLCD. In conversations with local herders and foresters, this research group provided photos of different parts of the local landscape and asked what they would be called. Using GIS software, the team created a map of classifications using the categories used by these local groups and compared it to the one created for government use, finding multiple discrepancies. In one case, land labeled as just ‘forest’ by government offices fell into three different categories for foresters based on their use of the land. By creating maps based on local knowledge and understandings of the landscape, participatory mapping became a tool for these local groups to shape future land use planning.

Participatory mapping has developed into a valuable approach for addressing issues such as environmental justice, housing security, and vulnerability to climate change. Participatory mapping has been used in many contexts and involves people from all walks of life. Particularly noteworthy is how maps produced through participatory mapping increasingly represent the perspectives of Indigenous and socially marginalized groups. These communities have too often been subject to top-down dictates from governments and companies who have used mapping and geospatial methods in ways that ignore local knowledge and priorities. Furthermore, these mapping tools can be used by these groups to assert their rights and advocate for the welfare of their communities.

9.4 Digital Divides

While there are many new possibilities for mapping, there are also huge disparities in terms of who has the technology, skills, and time to create data and maps. The “digital divide” between those who have access to technology and those who don’t is evident at multiple scales. Wealthy countries like the United States have faster, cheaper internet service, more comprehensive access to computers, and more resources devoted to the creation of geospatial data than developing nations. It is estimated that up to a quarter of the world’s population does not have access to electric power, much less the technology necessary to generate digital data or maps about their experiences.

Digital divide. Map of the cost of broadband subscription as a percentage of average yearly income.

This digital divide has resulted in a large discrepancy in the quantity and quality of data created for different parts of the world (e.g., lower spatial and attribute resolution in poorer countries.) This also means that international organizations continue to have more influence in shaping maps and narratives about developing countries than the people who live there.

The digital divide is also evident in smaller areas within wealthy countries and cities. There are strong differences in the speed of Internet connections and the use of new map technology between urban and rural areas. There are also notable divides in the use of technology based on socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. Who owns smartphones or other devices that leave a digital footprint? Who has the time and resources to volunteer geographic information? Unsurprisingly, data is more often produced by citizens from wealthy, tech-savvy urban neighborhoods than from poor, rural places. This results in inconsistent accuracy in data for different places on the map. In sum, just because new technology provides the possibility for more widespread participation in mapping, that does not guarantee that this participation will be equitable without appropriate technologies and the existence of supportive social, economic, and political institutions.

9.4.1 E-Waste

With rapid changes in new technology, the lifetime of electronic products is often very short. Cell phone and computer companies encourage customers to trade in their devices for newer models every couple of years or even yearly. Hundreds of millions of used computers, monitors, TVs, mobile phones, and other electrical products are thrown away annually. An estimated 57 million tons of electronic waste (e-waste) were generated worldwide in 2021 alone (Gill 2022). Electronic components frequently contain hazardous substances such as lead, mercury, and cadmium and must be disposed of carefully to avoid negative environmental consequences. So what happens to all of these used and broken electronics?

Trade agreements, such as the Basel Convention (1989), attempt to restrict the flow of e-waste from country to country. There are many loopholes, however, and a thriving black market has developed in some locations. Indeed, border agents checking shipping containers leaving the European Union found that almost one in three contained illegal e-waste. Waste has become particularly concentrated at ports in the developing world, such as Guiyu, China, and Agbogbloshie, Ghana. Impoverished individuals in these places have become experts at pulling apart electronic circuitry to sell the most valuable components, as seen below. Many techniques for disassembling electronics, such as burning plastic casings to get to the recyclable metals, have serious health effects.

The human toll of e-waste. People working to process electronic waste in Agbogbloshie, Ghana, moving material (left), and burning components for copper (right).

9.5 Counter-Mapping

Maps are social because power dynamics influence everything about mapmaking. These dynamics include who is considered an authoritative mapmaker, which data are present on and absent from maps, and which values and worldviews are embedded in maps. Sociologist Nancy Peluso coined the term ‘counter-mapping’ in 1995, based on her work with community-based mapmakers in Kalimantan, Indonesia (Peluso 1995). In Indonesia, maps of forest resources have long been political, with implications for forest protection and exploitation alike. Maps produced by government authorities have often led to both timber and mineral extraction and disadvantaged local communities’ rights to the forest. In Kalimantan, Peluso documented community members’ use of mapping techniques, including hand-drawn sketching and the use of GPS software, to bolster the legitimacy of customary (in other words, not formally or legally codified) rights to land and uses of forest resources. Counter-mapping typically involves local communities controlling their own narrative and representation, challenging omissions within ‘official’ maps, and complicating oversimplified boundaries and borders.

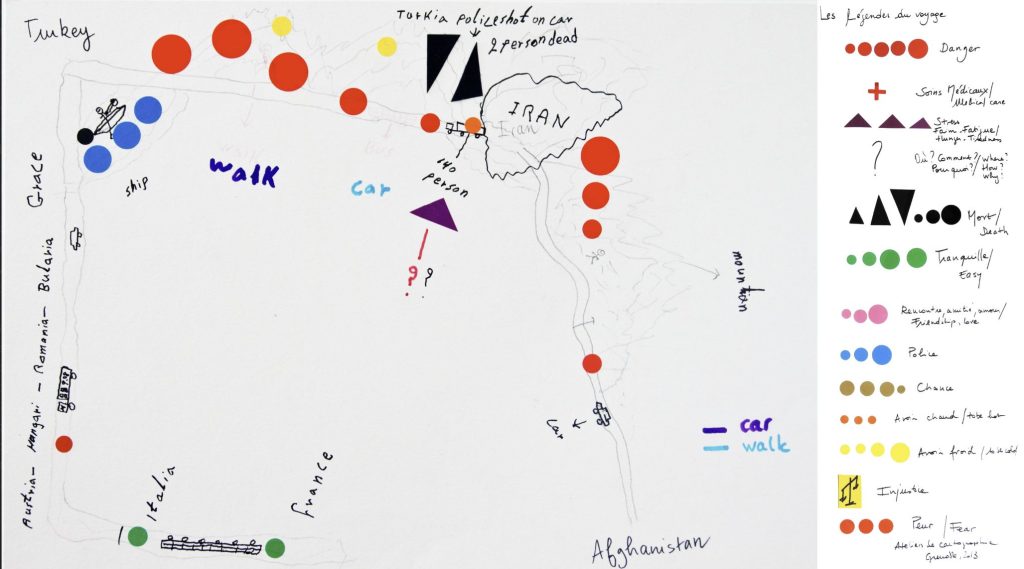

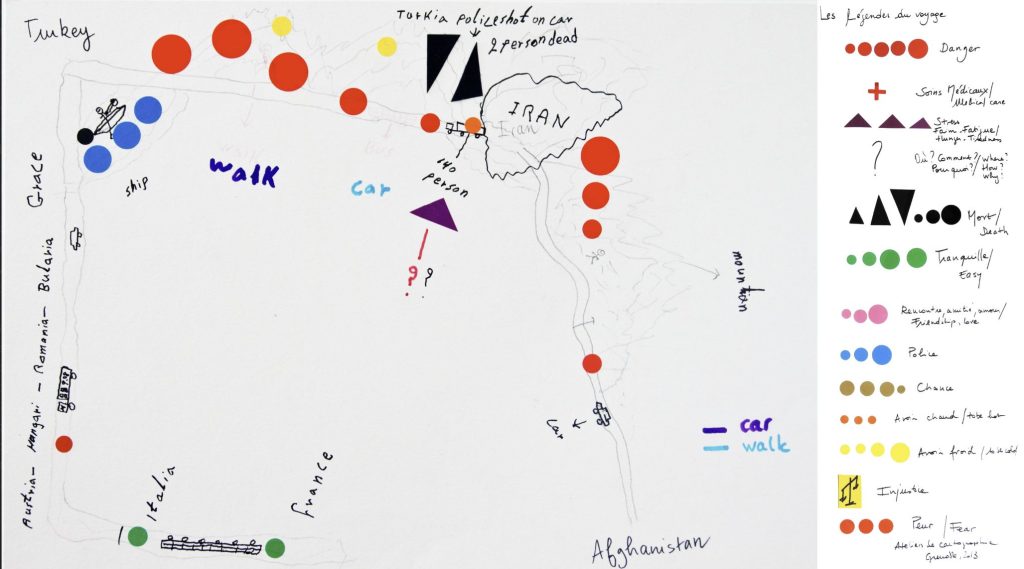

There are many different examples of counter-mapping around the world. For example, for researcher Amalia Campos-Delgado, cognitive maps created by migrant travelers moving north toward the US-Mexico border revealed the border to be far more mobile and fragmented than traditional maps usually depict. Campos-Delgado asked migrants in shelters south of the border to “draw their journey” north using paper and colored pencils (Campos-Delgado 2018). The resulting maps highlighted the emotional distress involved in leaving home, the violence and dangers involved in migration, the importance of safe spaces like shelters, checkpoints, and unofficial encounters with security personnel that extend very far from the actual border–none of which can be found on a standard map of the US southern border. Another example of a migration counter-map is portrayed below, which visually describes the route of a migrant from Afghanistan to France, and is presented on the site Not an Atlas. The map was developed during a workshop titled Crossing Maps that brought together artists, researchers, and asylum seekers. The map purposely mixes views from above and common elements such as place names, which many maps use, with more personal impressions on the ground, such as vehicles, police encounters, and dangers.

Migration counter-mapping. This map portrays the personal journey of a migrant seeking asylum in France after a long journey. The legend describes many features, including help, police, and danger. From the project Counter Cartographies of Exile: From France to Afghanistan.

Another example of counter-mapping can be found in the Native Land Digital project, which features a mapping interface with layers including Indigenous territories, languages, and treaties. Nation-state boundaries do not appear on this map unless the map viewer clicks ‘Settler Labels’ in the lower right-hand corner of the map, and even if this layer is enabled, it is more transparent, and thus less visible, than the Indigenous layers. These decisions by the Native-led mapmaking team produce the powerful effect of decentering settler geographies and offering map viewers a window into an Indigenous world.

Native Land Digital. Mapping interface with layers including Indigenous territories, languages, and treaties.

Colonial representations of space have been challenged in specific places by Indigenous people for various purposes. For example, Jim Enote, a Zuni farmer and museum director, has been collaborating with Zuni mapmakers for years to create maps of Zuni homelands that recenter Zuni place names and incorporate the cultural and spiritual aspects of the land–information usually omitted from colonial maps of the territory in what is today New Mexico (Steinauer-Scudder 2018). Further south, the Waorani people are using maps in the Amazon to fight against the Ecuadorian government’s plans to auction their land to oil companies. The Waorani worked with local partners and the US-based NGO Digital Democracy to roll out a community-based mapping strategy, entailing sketching by hand, collecting GPS points to match the community-identified features, and producing and revising draft maps based on community input.

The project team built and utilized a new mapping application called Mapeo, which allowed the Waorani to retain ownership over their intellectual property throughout the process, work with their data offline, and build maps themselves. The resulting maps digitized the locations of animal trails and habitats, burial sites, waterfalls and fishing holes, tree groves, and other kinds of cultural, historical, and spiritual sites that would be destroyed if oil companies were allowed to begin extraction. These maps look very different from the official maps of the region produced by the Ecuadorian government, which typically depict an empty green forest with a few small dots indicating the presence of Waorani villages. The Waorani maps were a decisive tool in a legal case the Waorani brought against the Ecuadorian government to fight the sale of their land, which they won in 2019 with a court ruling that the government had violated the Waorani’s right to free, prior, and informed consent. In this case, the maps helped demonstrate that far from being empty, the forest that the Waorani call home is rich with environmental, cultural, historic, and spiritual significance. .

9.6 Digital Maps, Real World

Digital maps shape the way that we move through and think about space. Most of the time, this is very helpful, as when we use phones to navigate from one place to another. Digital maps are also increasingly used to help guide us to specific kinds of destinations, such as the nearest gas station or coffee shop, as well as to provide information such as open hours or reviews. There can be downsides to these very helpful technologies, however.

GPS-enabled devices have become vital to the way we navigate from place to place. With the help of a smartphone, you can arrive in a new city and, without knowing anything about the area, find your hotel or locate a popular restaurant. Increasingly, people trust the route-planning algorithms embedded in online maps rather than their knowledge of an area or paper maps. There are many examples of obedient drivers following flawed directions from their GPS units into dangerous situations, including driving into lakes, onto airport runways, or on roads not suitable for the size of their vehicle. While you might urge individuals to pay more attention to their physical surroundings, it is undeniable that the internet, our phones, and Google Maps mediate our movements through space. An estimated one billion people use Google Maps every month. We are increasingly reliant on GPS to help us get from one activity to another. In one study in England, four out of five 18- to 30-year-olds confessed to an inability to navigate without electronic help (Ward 2013).

Google and other search engine listings impact where we choose to shop, eat, and spend our free time. When trying to find the nearest restaurant or get information about a business, many people turn to Google Maps. So, where does Google get its data? The bulk of the information in Google Places (Google’s business directory) comes from commercial mailing list databases, but ordinary users can also edit details such as phone numbers or hours of operation. This means rival companies can spam or hack a listing if it is not actively maintained by the real business owners.

An example of how someone can modify online directories is demonstrated by the fate of the Serbian Crown, a restaurant serving hearty Serbian fare for 40 years at the same location. The restaurant was forced to close in 2013 after seeing a sudden 75% decline in customers on the weekends. The puzzled owner eventually discovered that Google Places had been changed to incorrectly report the store as closed on Saturdays, Sundays, and Mondays. This service allows anyone with a Google email address to modify the information about a real place. Most of the time, this is helpful because anyone can correct an error, but sometimes this functionality can harm real people. Google has gotten better at monitoring these so-called ‘community edits’ but still has trouble tracking fake map listings.

9.7 Conclusion

Rapid changes in technology have greatly expanded who can create data and maps. These changes hold exciting possibilities for scientific research, disaster relief, government practices, social justice, and representing/navigating daily life. However, it is also important to acknowledge that the benefits of these innovations are not equally dispersed. Large portions of the global population do not have consistent access to electricity, much less the kinds of spatial data and techniques discussed in this chapter. Maps have a profound impact on the ways we move through the world and perceive space. As we have discussed in this chapter, mapping technology has changed significantly over time, with both positive results, like greater participation in data creation, and negative ramifications, like the digital divide.

References

Campos-Delgado, A. 2018. “Counter-mapping migration: Irregular migrants’ stories through cognitive mapping.” Mobilities 13(4): 488-504.

Gill, V. 2022. Mine e-waste, not the Earth, say scientists. BBC.

Holder, S. 2018. Who maps the world? Bloomberg.

Peluso, N. 1995. “Whose woods are these? Counter-mapping forest territories in Kalimantan, Indonesia.” Antipode 27(4): 383-406.

Ryan, A. 2019. Maps in court and the Waorani victory. Digital Democracy.

Steinauer-Scudder, C. 2018. Counter Mapping. Emergence.

Ward 2013. Four out of five young drivers can’t read a map as we become more reliant on satnavs. Daily Mail.