2 Starting a Writing Box Eight-Week Program

We ask librarians to create “purposeful programs.” Purposeful writing by young writers might include postcards, greeting cards, bookmarks, brochures, menus, ads, personal notes, maps, lists, book recommendations, and newspapers. Even the youngest writers can understand the purpose of these writing formats. And unlike the completion of a tedious worksheet, the creation of products like these is an authentic writing experience.

At the beginning of each Writing Box workshop, we ask writers to engage thoughtfully with a piece of literature or text as a prompt to their writing. When we talk about memoir, I might, for example, begin a workshop by talking about families. There are all different kinds of families. My mentor texts might include Susan Kuklin’s Families, Todd Parr’s The Family Book, and John Coy’s Their Great Gift: Courage, Sacrifice, and Hope in a New Land.

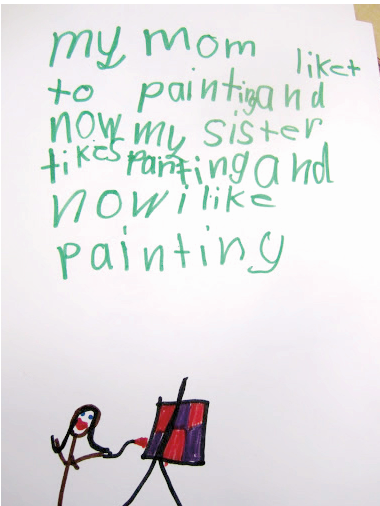

I would then read aloud Dan Yaccarino’s All the Way to America: The Story of a Big Italian Family and a Little Shovel. On the surface, this is an immigration story. Delving a little deeper, however, we discover that it is about what gets passed down in families: objects like shovels or pieces of clothing, genetic traits like curly hair, aptitudes like a talent for singing or drawing. As we reflect on the story, I chart these sorts of things on an easel pad. I may also suggest that we can write about what we hope to pass down to the next generation. (Some children do not have families where objects are passed down, are not with their biological parents, are with temporary caregivers, or have experienced devastating life events like evacuation or fires or homelessness). I may mention that I wish to pass down my love of reading or my knowledge about teaching.

As we begin to look at the details of setting up a Writing Box program, it’s important to recognize that as public librarians we are not imitating school practice. During summer reading programs, we are not teaching children to read, and during Writing Box programs, we are not teaching children to write. We know that self-selection of materials is a key component for readers who are choosing to read. Similarly, we are facilitating writing as a self-selected activity.

On the other hand, partnering, collaborating, and consulting with literacy specialists, classroom teachers, and after-school programs is to be encouraged, as these educators enrich and support our own programs and practice.

The public library can give children and adolescents opportunities to develop their literacy skills outside of the confines of school and the classroom. Just as librarians are charged with the mission of providing materials for the “freedom to read,” we must also provide the “freedom to write.”

The skills required for the themes described in this book build upon each other. A writer who can draw can make a map, and a writer who can make a map can dictate labels for it. A writer who can draw and write can make both a map and a label. A writer who can draw and label maps can tell a story. A story can be told by drawing pictures and labeling with words, and a writer can dictate a story to accompany the pictures. As writers gain confidence in their own written words, the workshops ask for more and more writing as the weeks go on.

Mentor Texts

Mentor texts—books or materials that model writing for our writers—are essential to the success of a Writing Box program. Writers can use these texts as inspiration: “I want to do a map like that!” “I LOVE Baby Mouse. I am going to write a story about yesterday in gym class but they are going to be kittens instead of mice.”

Think about diversity when selecting mentor texts, and about, as Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop notes, the importance of books providing windows to other lives as well as mirrors to our own.

It is likely that many of the mentor texts suggested in the chapter lists are already in your library. Planning a Writing Box program is a terrific excuse to refresh your collections in these subject areas.

More about selecting mentor texts in Chapter 4.

Starting A Writing Box Program

Post on large chart paper and read aloud the Bill of Writes at each session. Sometimes I ask another grown-up to do the read aloud.

A Bill of Writes (adapted from Kids Have All the Write Stuff)

- I write to please myself.

- I decide how to use the Writing Box.

- I choose what to write and know when it is finished.

- I am a writer and a reader right now.

- I have things to say and write every day.

- I write when I play and I play when I write.

- I can write about my experience and my imagination.

- I enjoy writing with technology.

- I spell the way I can and learn to spell as I write.

- I learn as I write and write as I learn.

Begin with a plan

To begin, you need to create a workshop plan. For example, in the public library setting, I suggest the following topics. They are ordered in a way that helps participants build their skills, starting with the simple skill of map making and moving to more complicated writing activities.

- Maps

- Cartoons

- Menus and Recipes

- Hieroglyphics

- Newspapers and Newsletters; Blogs, Facebook, and Twitter

- Postcards and Letters

- Poetry

- Handmade Books

Each workshop should be one hour long, and each suggested program has five common elements:

- Books or materials related to the topic; we call these mentor texts

- Creation of an example by the librarian

- Modeling of the action of writing

- A simple interaction with the children

- Writing Boxes, which are available for reference checkout during library hours from the reference, information, or circulation desk.

Finding a good space

It seems self-evident, but the next step is to find a good space for writing. The children’s room is fine. Tables and chairs are great but not essential. My school library had moveable soft furniture and wooden stools and benches. We did all of our writing on clipboards. Children wrote sitting up, lying down, wherever they were most comfortable.

While libraries are not the shushing quiet spaces of yesteryear, it is good to remember that writing is a noisy business. Children and young adults are not quiet when they’re excited about their work. Find a room or a space where noisy activity does not disturb others.

Who should participate?

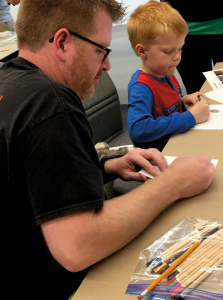

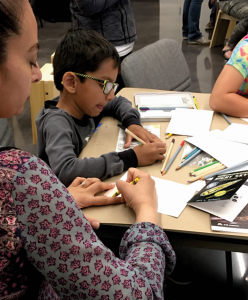

The Writing Box program was initially designed for the school-aged child, but we discovered there was no reason to limit attendance by age. Welcome anyone who wishes to write to participate in the program. This means moms and dads, caretakers and babysitters, sisters and brothers, teachers and grad students—whoever is interested. Sitters can write postcards home while babies are asleep in carriages. Grandfathers have discovered their own artistic and writing talent while creating comic memoirs.

Supporting and separating the grown-ups

The Writing Box program should not be a drop-off program. In our libraries, all children ages eight and younger were required to have an adult in the room or nearby (within sight). Encourage adults to actively participate and create their own writing pieces.

You might need to separate an adult from a child if the adult becomes too involved with their child’s writing. Announce this possibility at the beginning of the program, speaking directly to the adults after reading aloud the “Bill of Writes.” You can use language like this:

“Grown ups. I know it’s hard to sit back as your child misforms letters, misspells easy words or asks “how do you spell cow?” It’s hard to break the habit of perfectionism.

“If your child is young, ask if you can take dictation. If your child knows how to write, perhaps move to another table or say ‘I am working on my own writing, why don’t you try to do it on your own for awhile and we can edit afterwards?’”

Adults often making critical comments while a child is writing. “You know how to make your r’s better than that.” “That’s not how a map is supposed to look.” “Is that all you are going to write?” “That’s not how you spell dinosaur.” are examples of over-involvement. Encourage the adults to focus on their own work, or keep their eyes on their own papers. Remind them that writing is not editing, and that there will always be time for editing later.

Practical advice

Writers can be pre-registered, or workshops can be open access. I have used both systems. Librarians know their populations best.

At the Brooklyn Public Library, we found that our teen book buddies (ages 12 and up) were a terrific help in the preparation, maintenance, and checking in and out of our Writing Boxes. The young adults enjoyed the responsibility of being in charge of these elements of the program. In my school library, we had library helpers from the fourth and fifth grades charged with retrieving books and stocking supplies. These older helpers can all take dictation from the younger writers and listen as they share their work.

Helpful Hints

- Set up the room with books, placed face out, on the related topic.

- Model the writing activity and verbalize why you are doing it: “I am drawing a map. Here is my house. I am writing ‘my house.’ I am listing who lives in the house. What is across the street? The firehouse is across the street. I am writing ‘Firehouse.’”

- Encourage adults to join in—not to observe, but to participate. You might say, “Mrs. Fox, is there anyone that you would like to send a letter to?”

- Encourage older children to help the younger ones at their table, but keep in mind that they should also have their own writing experience.

- Have a dictionary or online spelling resource available, but encourage the children not to worry about spelling and don’t let them get bogged down by it. Remind them that we are writing, not editing.

- In the Writing Box program, there is no place for awards, ribbons, or prizes. The process IS the product.