17 Publishing: Writing & Revision, Process & Product

Sharing our work

What now? Teachers are partnering with librarians to create safe spaces to read, write, and share. Paper, pencils, markers, and mentor texts are readily available. Kids of all ages are writing. Writers are creating poetry and newspapers, writing family recipes and sending postcards, making cartoons and mapping imaginary lands. We’re reading, and we’re excited about writing.

At one time, I did think that the writing was enough. I was a convert to the “process, not product” school of thought, in which the journey was the most important part of writing. I read everything I could find about teaching creative writing and about the whole language movement.[1] But as I developed and conducted writing workshops, I discovered that writers were eager to share their work. This sharing had become an essential element of the Writing Box experience.

We know children understand that writing is a way to communicate. At an early age, they can communicate by writing and/or dictating lists, menus, letters, and labels. Social media is all about communication and validation, which often comes easily, such as by getting “likes” on a Facebook page. On the other hand, some young writers have never had positive attention paid to their creative and informational writing.

826

It was with my volunteer work with 826 Minneapolis that I internalized the importance of publishing the work of young writers.

Dave Eggers, the publisher of McSweeney’s, had many friends and family members who were teachers, and who told him that many of the issues with illiteracy and achievement gaps could be addressed and in part resolved by providing one-on-one attention to struggling learners. The 826 model developed from an after-school drop in homework-help program into one encouraging adult volunteers to drop in for two hours whenever they could. I can attest to the transformative power of this simple program for creating and sharing the written word.

826 National arose from a tutoring center called 826 Valencia, named after its street address in the heart of San Francisco’s Mission District. 826 Valencia opened on April 8, 2002, and consists of a writing lab—a street-front, student-friendly, retail pirate supply store (that sells scurvy water and captain’s logs) in the front that partially funds the programs—and three satellite classrooms in nearby elementary, middle, and high schools.

The Wallace Foundation’s Something to Say: Success Principles for Afterschool Arts Programs from Urban Youth and Other Experts, by Denise Montgomery, evaluates the 826 National programs. Montgomery finds that the programs’ success is due not only to the consistent and growing attendance of participants but also to 826 National’s ability to raise visibility through stakeholder ties.[2]

What does it mean to publish?

For a librarian, “to publish” means to publish professionally—to go through the publication process that includes editors, copy editors, and publishing or media companies who create a product and sell it in the marketplace.

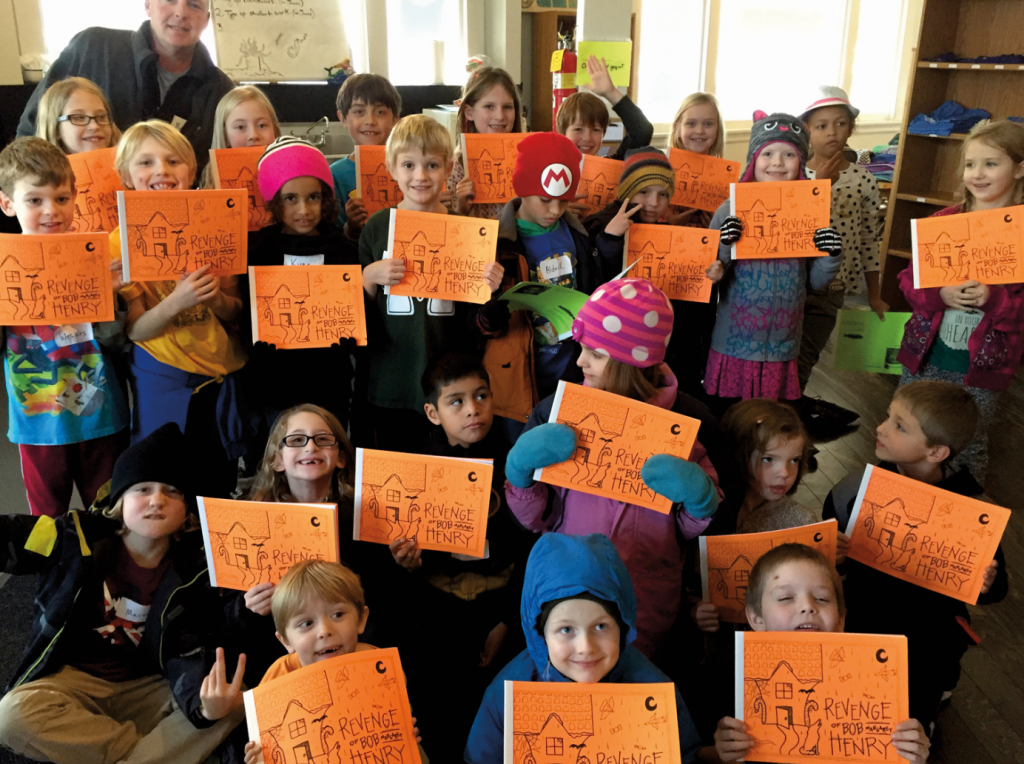

But publishing can also mean simply sharing our writing: reading aloud, for instance, to an audience of one, or of thirty. Or making physical copies—one handmade book, or a collection of 30 stapled, bound copies of the same title. Technology today enables us to bind a paperback book of our writers’ collected works. The validation and joy that comes from holding a physical book, produced and distributed by its writers, cannot be measured. The outcomes can.

The work of 826 National and its Minneapolis affiliate, the Mid-Continent Oceanographic Institute, persuaded me that publishing can be done in many forms, and that publishing/sharing the work should be part of any writing program.

I witnessed this excitement in 55 fifth-grade writers who contributed short stories to Up, Up and Away: Advice and Adventures from the Future Authors and Astronauts of Farnsworth Aerospace. They read aloud with confidence during their publication party. Their families—fathers and mothers, grandparents and cousins, aunts and uncles—beamed with pride as the authors signed their pages of the finished book.

Lauren Broder, PhD, director of research and evaluation of 826 National, confirmed the importance of publishing as one of the cornerstones of their program, and reiterated the importance of outside validation to support and inspire the young writers’ work. (For more information about 826 National, contact Dr. Broder at laurenb@826national.org, 415. 864.2098.)

In his TED talk of February, 2008, Dave Eggers spoke of the value of the volunteer tutors, who sit “shoulder to shoulder” with the writers and whose “concentrated attention shining this beam of light on [the writers’] work, on their thoughts, on their self expression … is absolutely transformative because so many of their students had not had that before.”

Young writers who know that their work is going to be published work hard. They revise and revise and revise to create a product worthy of publication.

Eggers stated that the 826 program also succeeded because there was no stigma attached to going to the pirate supply store. The kids who come for tutoring see themselves as the cool kids.

An 826 tutoring/writing center is a place where young writers’ opinions and thoughts are of value. A library with a Writing Box program can be a similar safe place, where children and young adults can improve their literacy skills. Librarians who provide a platform for sharing writers’ work are confirming the value of the children’s writing. Isn’t that the goal of every library’s children and young adult services program?[3]

Means for sharing the writing product

Children can share one-on-one with parents, teachers, or peers. We can post work on bulletin boards or tape it to walls and windows. We can take photographs and scan and upload them to websites, create handmade books or newspapers or zines. These are all forms of publishing. The writing product can be shared internally or disseminated to families or classes or buddies or to the community. The physical product of writing in any format creates a reality that this work is worthy of sharing.

A few words about revision

I recently had the opportunity to speak to a mom about a school assignment on which her young adult daughter was procrastinating. The daughter had a draft, but the mom felt it wasn’t completed. The daughter didn’t have any problem writing; in her mom’s opinion, the kid had stalled in the revision process.

My advice wasn’t very satisfying. Mostly I said “back off.” The teacher here is really the editor, who will note unclear word choices and atrocious spelling and grammar. The writing was the joy. The revision is the work that makes a piece readable/publishable.

And then I remembered mentor texts. In the Children’s Literature Research Collections of the University of Minnesota, where I am the curator, we have boxes and boxes, files and files of corrected and revised manuscript pages from children’s and young adult writers like Sharon Creech, Christopher Paul Curtis, Katherine Paterson, and Kate DiCamillo.

To illustrate the revision process, I have included here the first page of the first draft of Because of Winn Dixie, of the fourth draft, and of a draft very close to the published first page. Newbery medal winner DiCamillo told me that she donates her papers to the Kerlan Collection because she wants all children to know that writing begins with a big mess. And she wants adults to know that writing begins with a big mess.

Resources

826 Valencia, and Miranda Tsang. 2014. 642 Things to Write About. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Aliki. 1986. How a Book Is Made. New York: Crowell.

Asher, Sandy, and Susan Hellard. 1987. Where Do You Get Your Ideas? Helping Young Writers Begin. New York: Walker.

Bauer, Marion Dane. 1992. What’s Your Story? A Young Person’s Guide to Writing Fiction. New York: Clarion Books.

Benke, Karen. 2010. Rip the Page! Adventures in Creative Writing. Boston: Trumpeter.

Bulloch, Ivan, Diane James, and Toby Maudsley. 1991. The Letter Book. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers.

Calkins, Lucy. 1986. The Art of Teaching Writing. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Cleary, Beverly, Paul O. Zelinsky. 1983. Dear Mr. Henshaw. New York: Morrow.

Fletcher, Ralph J. 1996. A Writer’s Notebook: Unlocking the Writer within You. New York: Avon Books.

Guthrie, Donna, Nancy Bentley, and Katy Keck Arnsteen. 1994. The Young Author’s Do-It-Yourself Book: How to Write, Illustrate, and Produce Your Own Book. Brookfield, CT: Millbrook Press.

Hambleton, Vicki, Cathleen Greenwood, and Vicki Hambleton. 2012. So, You Want to Be a Writer? How to Write, Get Published, and Maybe Even Make It Big! New York, NY: Aladdin: Beyond Words.

Hawkins, Lisa K, and Abu Bakar Razali. 2012. “A Tale of 3 P’s—Penmanship, Product, and Process: 100 Years of Elementary Writing Instruction.” Language Arts 89 (5):305–317.

Initiative, Common Core Standards. “English Language Arts Standards.” z.umn.edu/wbr75.

Irvine, Joan, and Barbara Reid. 1987. How to Make Pop-Ups. New York: Morrow Junior Books.

Janeczko, Paul B. 1999. How to Write Poetry, Scholastic Guides. New York, NY: Scholastic Reference.

Katzen, Mollie, and Ann Henderson. 1994. Pretend Soup and Other Real Recipes: A Cookbook for Preschoolers & Up. Berkeley, CA: Tricycle Press.

Keats, Ezra Jack. 1998. A Letter to Amy. New York: Viking.

Kennedy, X. J., Dorothy M. Kennedy, and Jane Dyer. 1992. Talking Like the Rain: A Read-to Me Book of Poems. Boston: Little, Brown.

Kessler, Leonard P. 1986. Old Turtle’s Riddle and Joke Book. New York: Greenwillow Books.

Loewen, Nancy, and Christopher Lyles. 2009. Sincerely Yours: Writing Your Own Letter, Writer’s Toolbox. Minneapolis, MN: Picture Window Books.

Mavrogenes, Nancy A. 1987. “Young Children Composing Then and Now: Recent Research on Emergent Literacy.” Visible Language 21 (2):271.

Shaskan, Trisha Speed, and Stephen Shaskan. 2011. Art Panels, Bam! Speech Bubbles, Pow! Writing Your Own Graphic Novel, Writer’s Toolbox. Mankato, MN: Picture Window Books.

Traig, Jennifer. 2015. Stem to Story: Enthralling and Effective Lesson Plans for Grades 5–8: Jossey-Bass.

Williams, Vera B. 1981. Three Days on a River in a Red Canoe. New York: Greenwillow Books.

- Goodman, Kenneth S. (1992) "I Didn't Found Whole Language," The Reading Teacher 46(3) pp. 188-199 ↵

- Montgomery, Denise. 2013. Something to Say: Success Principles for Afterschool Arts Programs from Urban Youth and Other Experts. New York: Wallace Foundation. ↵

- Competencies for Librarians Serving Children in Public Libraries, created by the ALSC Education Committee, 1989. Revised by the ALSC Education Committee, 1999, 2009, 2015; approved by the ALSC Board of Directors at the 2015 American Library Association Annual Conference. ↵