15 Combining Workshops

For me it is sometimes impossible to select one theme. Would this be a poetry response? Would it be cartoons? Why can’t it be both?

Just as librarians emphasise the importance of self-selection of titles to read, the Writing Boxes program encourages self-selection in writing formats. These “containers” for writing—cartooning, mapping, poetry, and so on—, and so on—can be sparks to writing practice. We provide the materials and format, then let go.

When I am selecting mentor texts, often a title is suitable for more than one writing response.

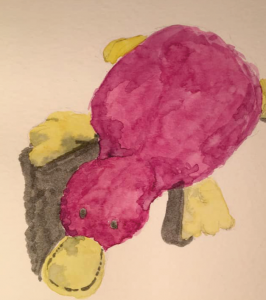

An example of this would be memoir. I might, for example, read aloud Bubba and Beau: Best Friends by Kathy Appelt, illustrated by Arthur Howard. This picture book about a baby and a puppy and their favorite pink blankie is the perfect prompt for workshop participants to remember their own beloved comfort objects, like a stuffed platypus. We can then list the attributes of Patty on chart paper:

- Platty was/is a dark cherry color.

- Platty has a duck bill.

- Platty is shaped like a three-pound avocado.

- Platty was as long as my arm when I was four-years-old.

- Platty’s head fit right under my chin when I went to bed.

- I liked to chew on his front feet.

I can create a cartoon that has each of these statements and a picture in one square.

We might also start with a memoir prompt like “Where I’m from,” and that can become a memoir cartoon. A mentor text for this would be Hey, Kiddo, written and illustrated by Jarrett J. Krosoczka.

Best selling graphic artist Raina Telgemeier (The Baby Sitters Club, Smile, Drama, Sisters) created a guide for anyone who wishes to write their memoir in comic format. In Share Your Smile: Raina’s Guide to Telling Your Own Story, Ms. Telgemeier provides suggested writing prompts like looking through family photographs, and talks about jotting down our own memories. The book contains practice pages for drawing your family members along with cartoon templates. Just as we do in the Writing Box sessions, Telgemeier shows how she would draw and write her travel story from her own childhood.

A recent public program

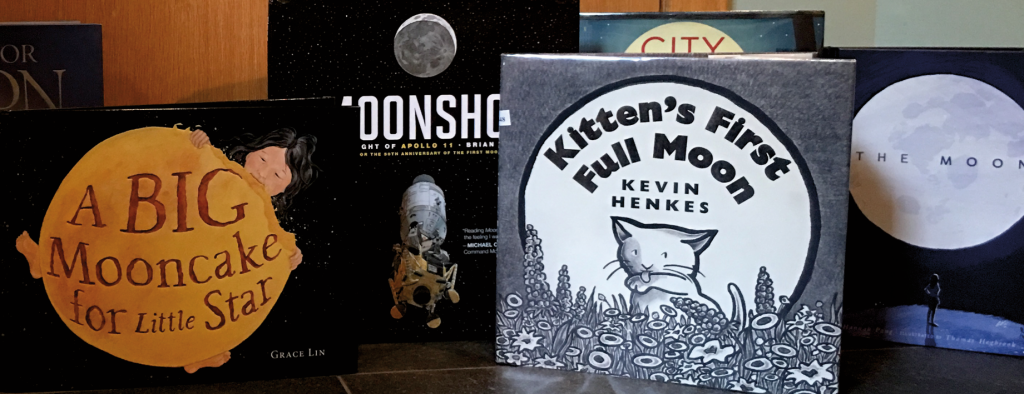

For the 50th anniversary of the moon landing, I was asked to do an evening pajama party read aloud. I didn’t know the ages of the participants in advance. The session was one hour long. I gathered mentor texts: poetry like Moon Have You Met My Mother, by Karla Kuskin; picture books like Kevin Henkes’ Kitten’s First Full Moon, A Kite For Moon by Jane Yolen and Heidi Stemple, and Grace Lin’s Big Mooncake for Little Star; story collections like Thirteen Moons on Turtles Back by Joseph Bruchac; and informational books like Brian Floca’s Moonshot and Moon! Earth’s Best Friend by Stacy McAnult. I displayed factual texts, books about the planets and the solar system, and a richly illustrated, oversized volume titled Planetarium. And I provided Writing Boxes and postcard templates for a writing response after the read alouds.

We had over 300 attendees who were scheduled in two sessions, at 7:00 pm and 8:00 pm. In each session, I read aloud for half an hour, then we wrote poems and postcards; three young participants spent that time fact checking in the reference books.

HeartMaps

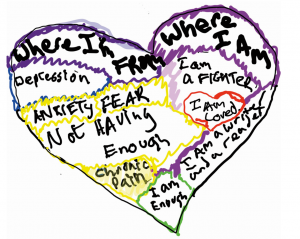

In Heart Maps, Georgia Heard shares 20 unique, multi-genre heart maps to help writers, young and old, to write from the heart. Her suggested formats include the First Time Heart Map, Family Quilt Heart Map, and People I Admire Heart Map. Heard’s clear, concise instructions and inspiring prompts help the writing mentor librarian produce a workshop that will facilitate authentic writing. Heart Maps are the perfect activity for intergenerational programming, helping families sharing stories.

With Heard’s permission, I am sharing this uniquely creative process. For my example, I first brainstormed from the “where I’m from” prompt, thinking about struggles of my childhood and young adulthood. Then I thought about where I am now. Here is my heart map.

Zines

Zines are also included in the chapter on newspapers and zines, and in the publishing chapter. Zines are generally defined as self-published, small print-run publications. Often, zines are written by and for a community whose members are enthusiasts of a certain subject or literary genre.

All you need for a zine is paper, a copy machine, and a stapler. (May I suggest the Bostitch No-Jam Booklet Stapler.)

Jenna Freedman is a librarian, zine maker, and zine librarian who manages the zine collections at Barnard College Library in New York City. In Zine Librarian Zine: DYI-IYL, Do it Yourself in Your Library, she describes how to catalog and preserve a zine collection—helpful information not only for creating a collection of mentor texts for program participants, but for pitching a collection to administrators. This zine was edited by Rachel Murphy, Jenna Freedman and Alycia Sellie, with the blessing of the original Zine Librarian Zine-ster, Greig Means. The cover is designed by Torie Quiñonez.

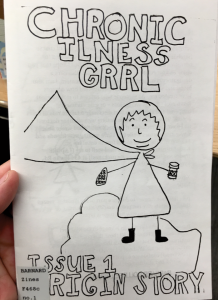

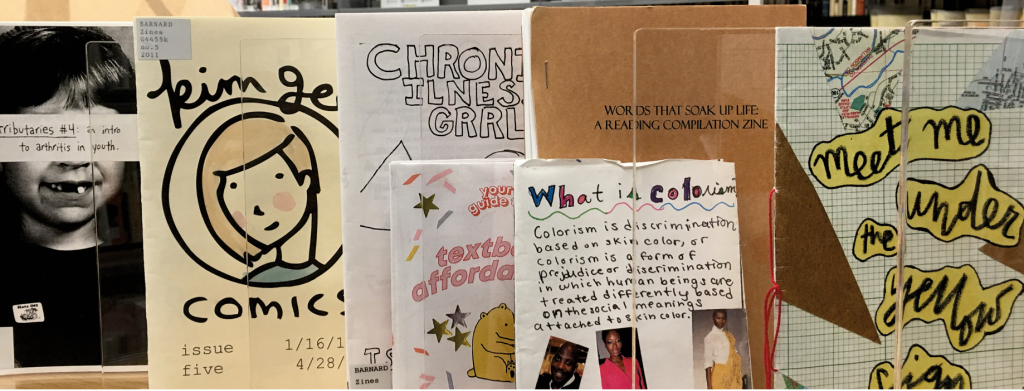

Zines can be also memoirs in comic format, like Chronic Illness Grrl #1: Origin Story, by Katie Tastrom. Or a librarian might partner with a classroom teacher— like a health teacher—for a research project. JC Parker, an eighteen-year-old from D.C., created Tributaries #4: An intro to arthritis in youth using factual information illustrated with out-of-copyright images digitized from the National Library of Medicine.

In combining workshops, it’s easy to see how a class collections of poems or recipes or cartoons or informational text about butterflies can be transformed into a zine, perhaps in a bookmaking workshop, a culminating subject project, or as part of an out-of-school makerspace program. We might, for instance, look at the informational mentor texts about bees and create a new publication, like The Flower Lovers: a little zine about pollinators, No.1: Twelve Wild Bees.

The community of writers in a library may also wish to create a zine, with the mentor-librarian giving format guidance and suggestions about previous themes that could provide the content, including informational writing, cartoons, and poetry. The Phoenix Public Library, for instance, facilitates the creation of a teen zine, Create!zine—a publication by teens for teens in the Phoenix area that gives teens the opportunity to be published and to contribute to the arts in Phoenix.

Combining & Building on Workshops Prompts

- A letter to a friend from a previous neighborhood containing a map of the new neighborhood.

- A text message to Dad to containing the grocery list for the birthday cake.

- A letter to a fictional character with information they’ll need for their journey.

- A thank you note to an author whose books you love.

- A letter in a secret code.

- A letter with a recipe someone else gave you.

Resources

Arnold, Chloe. A Brief History of Zines. z.umn.edu/wbr60.

Krosoczka, Jarrett J. 2018. Hey, Kiddo: How I Lost My Mother, Found My Father, and Dealt with Family Addiction. Graphix.

Parker, J. C. 2014. Tributaries #4: An into to arthritis in youth.

Phoenix Public Library. Create!zine. z.umn.edu/wbr61.

Tastrom, Katie. Chronic Illness Grrl #1: Origin Story. z.umn.edu/wbr62.

Weber, Greta. Zines Deserve a Bigger Place in DC Punk History. Here’s Why. z.umn.edu/wbr63.