Chapter 5: The Sign

This chapter introduces the concepts of representation and the sign. These are counterparts to the theory of the symbol, and seek to account for the way that language acts both at a given historical moment and across different moments of time. The first part of this chapter adapts premises developed in the textbook Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, edited by Stuart Hall, Jessica Evans, and Sean Nixon.

The first (somewhat longer) section of this chapter addresses representation and the basic components of the sign, as theorized by Ferdinand de Saussure. It then describes the role of metaphor and engages the idea that the President (of the United States) functions as a sign for the reading, listening, and viewing public. The second part of this chapter is a recorded lecture from Dr. Belinda Stillion Southard of the University of Georgia. Dr. Stillion Southard addresses the relationship between language and beliefs by drawing upon the example of the suffragists and how they can teach us to be attentive to our language choices.

Watching the video clips embedded in the chapters may add to the projected “read time” listed in the headers. Please also note that the audio recording for this chapter covers the same tested content as is presented in the chapter below.

Chapter Recordings

- Part 1: Signs and Representation (Video, ~40m)

- Part 2: Change the Language, Change the Beliefs (Video also embedded below, ~14m)

Read this Next

- Norton, Anne. “Chapter 3: The President as a Sign.” Republic of signs: Liberal theory and American popular culture. University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Part 1: Signs and Representations

Here is a simple exercise about representation. Look at any familiar object in the room. You will immediately recognize what it is. But how do you know what the object is? Now try to make yourself conscious of what you are doing – observe what is going on as you do it. You recognize what it is because your thought processes decode your visual perception of the object in terms of a concept of it that you have in your head. This must be so because, if you look away from the object, you can still think about it by conjuring it ‘in your mind’s eye’.

Now, say what it is. The concept of the object has passed through your mental representation of it to me via the word for it which you have just used. The word stands for or represents the concept. It can be used to reference or designate either a ‘real’ object in the world or indeed even some imaginary object, like angels dancing on the head of a pin. This is how you give meaning to things through language. This is how we make sense of the world of people, objects, and events. It is also how you express complex thoughts about those things to other people in a way they are able to understand. That brings us to our first definition of representation.

Definition 1: Representation is the production of the meaning of the concepts in our minds through language. It is the link between concepts and language which enables us to refer to either the real world of objects, people or events, or to imaginary worlds of fictional objects, people, and events.

Definition 2: Representation means using language to say something meaningful about (or to represent) the world meaningfully, to other people. By this understanding, representation is an essential part of the process by which meaning is produced and exchanged between members of a culture.

How does the concept of representation connect meaning and language to culture? We will look at several theories about how language is used to represent the world.

Approaches to Language and Representation

We will distinguish between three different accounts or theories: (a) the reflective, (b) the intentional, and (c) the constructionist approaches to representation. In other words:

Reflective: Does language simply reflect a meaning which already exists out there in the world of objects, people and events (reflective)?

In the reflective approach, meaning is thought to lie in the object, person, idea, or event in the real world, and language functions as a mirror, to reflect the true meaning as it already exists in the world. As Gertrude Stein once said, “A rose is a rose is a rose.” In the fourth century BC, the Greeks used the notion of mimesis to explain how language, even drawing and painting, mirrored or imitated Nature; they thought of Homer’s great poem, The Iliad, as ‘imitating’ a heroic series of events. So the theory which says that language works by simply reflecting or imitating the truth that is already there and fixed in the world, is sometimes called ‘mimetic’. Language from this point of view is primarily denotative; it indicates the objective status of things.

Intentional: Does language express only what the speaker or writer or painter wants to say, his or her personally intended meaning (intentional)?

The second approach to meaning in representation argues the opposite case. It holds that it is the speaker, the author, who imposes his or her unique meaning on the world through language. Words mean what the author intends they should mean. This is the intentional approach. Again, there is some point to this argument since we all, as individuals, do use language to convey or communicate things that are special or unique to us, to our way of seeing the world. From this perspective, a speaker controls the intended meaning of their language, and correspondingly, steers how an audience might see or perceive them.

However, as a general theory of language, the intentional approach is also flawed. Our words sometimes have consequences that we do not anticipate. Other times, we can say more than we mean. What, for instance, is the role of intentions when we translate trauma experienced in one domain of our lives into words that we project onto other people? We cannot be the sole or unique source of meanings in language, since that would mean that we could express ourselves in entirely private languages. But the essence of language is communication and that, in turn, depends on shared linguistic conventions and shared codes. Language can never be wholly a private game. Our private intended meanings, however personal to us, have to enter into the rules, codes and conventions of language to be shared and understood. Language is a social system through and through. This means that our private thoughts have to negotiate with all the other meanings for words or images which have been stored in language which our use of the language system will inevitably trigger into action.

Constructionist: Or is meaning constructed in and through language (constructionist)? What kind of constructions are at play?

The third approach recognizes this public, social character of language. It acknowledges that neither things in themselves nor the individual users of language can fix meaning in language. Things don’t mean: we construct meaning, using representational systems – concepts and signs. Hence it is called the constructivist or constructionist approach to meaning in language. According to this approach, we must not confuse the material world, where things and people exist, and the symbolic practices and processes through which representation, meaning, and language operate. Constructivists do not deny the existence of the material world. However, it is not the material world that conveys meaning: it is the language system or whatever system we are using to represent our concepts. It is social actors who use the conceptual systems of their culture and the linguistic and other representational systems to construct meaning, to make the world meaningful, and to communicate about that world meaningfully to others.

Additionally, there may be several different kinds of constructions that are at play in a given instance of representation. One kind of representational construction is semiotic, which is based on language and shared meaning-making. Another kind of representational construction is discursive, which is a manifestation of power being exercised. Consider the clip below. Are the representations conjured by words like “freedom” and “terror” semiotic, discursive, or both?

George W. Bush’s 2001 Declaration of the “War on Terror”

The above clip from 2001 shows George W. Bush declaring “the war on terror” which initiated America’s 21st-century interventions in Afghanistan. Bush reuses words like “freedom” and “terror” over and over to create a web of representations and language that support the idea of an emergency or imminent threat. The argument that words construct our lived realities is brought to life here because Bush’s speeches constituted a reality of actual and ongoing warfare, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Iraqi people and a failed search for weapons of mass destruction. The representations conjured through this language created an impression of threat, danger, and fear. In turn, these representations produced a social reality that authorized an “endless” war.

Ferdinand de Saussure’s Theory of the Sign

Representations create a shared conceptual map for a body of people to use symbols to refer to similar ideas which are held in common. This shared conceptual map must be translated into a common language so that we can correlate our concepts and ideas with certain written words, spoken sounds or visual images. The general term we use for words, sounds or images which carry meaning is signs. These signs stand for or represent the concepts and the conceptual relations between them which we carry around in our heads and together they make up the meaning-systems of our culture.

The theory of the sign is most often attributed to the work and influence of the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure. Saussure. who was born in Geneva in 1857, did much of his work in Paris, and died in 1913. For our purposes, he is important for his general view of representation and the way his model of language shaped the semiotic approach to the problem of representation in a wide variety of cultural fields.

The production of meaning depends on language. As [Saussure] writes, ‘Language is a system of signs.’ Sounds, images, written words, paintings, photographs, etc. function as signs within language ‘only when they serve to express or communicate ideas … [To] communicate ideas, they must be part of a system of conventions ….” (Culler 1976, p. 19)

In an important move, Saussure divides the sign into two elements.

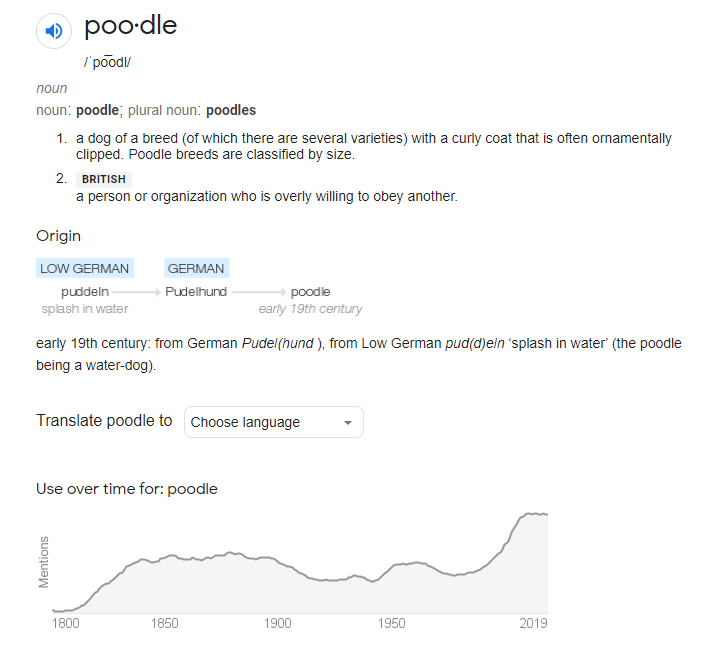

First, there is the “concept” or “meaning” of the sign; a shared idea. This is the signified. Every time your read, hear, or see “poodle,” it correlates to the concept of a floofy dog.

Second, there is the signifier: the form or sound-image (the actual word, image, photo, etc.) that consists of the different sounds that combine to create a word (P-O-O-D-L-E). can also be an image, such as the one shown below. The signifier is the material dimension of the sign. It may consist of the actual sounds we make with our vocal cords, the images made with cameras, the marks we use to write words or paint on canvas, or digital 1s and 0s we transmit electronically.

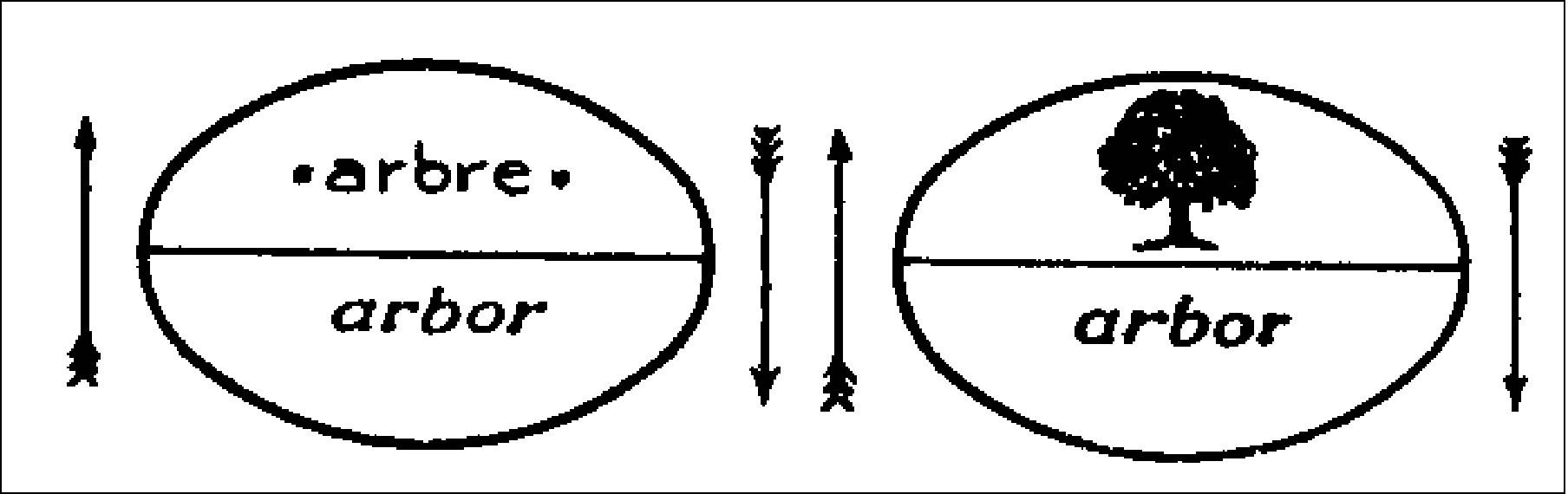

In his original diagram of the sign, Saussure places the signified over the signifier and separates them with a bar. This bar is meant to illustrate that the signifier (or sound-image) is only associated with the signified (or the implied concept) by convention. There is no necessary relationship between them. The bar is a visual reminder that a signifier (a word or series of sounds) may come to mean something different. Across or at a precise moment in time, a signifier may have different signifieds. Saussure also encloses the sign in an ellipse. This ellipse illustrates how the signifier and signified appear as if they are fixed. If I say the word “tree,” the meaning (a leafy living organism) seems as though it is permanently attached to this word. However, the sign illustrates that this association is only ever temporary at best.

Both the signifier and the signified are required to produce meaning, but it is the relation between them, fixed by our cultural and linguistic codes, that sustains representation. The sign is the union of the signifier and the signified. Although we can talk about them as if they were distinct or separate entities, they only exist as components of the sign, which is the central fact of language.

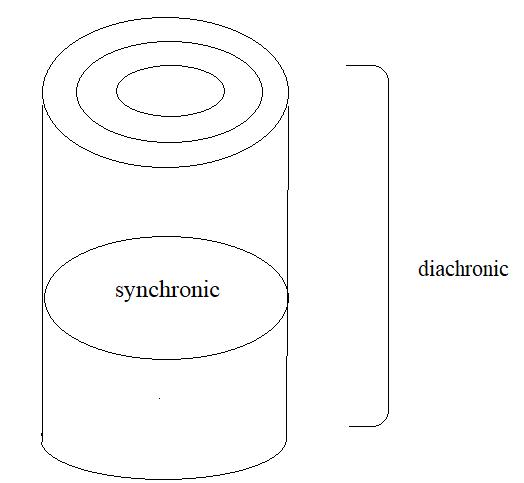

He also introduces a distinction between the “diachronic” and “synchronic” axes of language.

The diachronic refers to the transformation of signs over time. This is represented by the “vertical” (y) axis in the figure below. It is the time during which a language transforms and evolves. The diachronic axis draws attention to the sign’s meaning for all time. It describes the distinct associations of signifiers and signifieds across time and traces a path between them. As a given signifier acquires and sheds distinct signifieds, it may remain in use but with new meanings, uses, and effects across history.

The synchronic refers to “horizontal” or immediate time in which the sign exists. It is the “horizontal” (x) axis that refers to the individual synchronic snapshots of language’s meaning. These are the individual moments in time where the meaning of signs appears stable, natural, and normal. The synchronic dimension of language isolates the meaning of the sign as a relationship to other, related signs in a specific and historically defined instance. The synchronic meaning of the sign is what it means at a particular moment in time, and not what it means for ‘all time’.

Consider, for example, how many words there have been since the 1990s to describe the aversive emotional impact of the digital age: people have accused the age of the internet of causing information overload, the too-much-information effect (now just ‘TMI’), information anxiety, and (most offensively, but nonetheless a real term that was once used) infobesity. Each of these invokes a similar concept, anxiety at the quantity of information that is out there because of the internet. But the sign is arbitrary because in each case it is attached to a different signifier.

“Each language produce a different set of signifiers, articulating and dividing the continuum of sound (or writing or drawing or photography) in a distinctive way … each language also produces a different set of signifieds; it has a distinctive and thus arbitrary way of organizing the world into concepts and categories” (Culler, 1976, p. 23).

The language system that is the raw material of signs is used here in a very broad sense. Cultural norms of pronunciation and signification make Spanish, Swedish, Basque, Turkish, and English ‘languages’. However, photographs, cinema, and medical imaging (e.g. x-rays), all possess their own unique “languages” as well. Similarly, we might say that mathematics, computer science, physics, chemistry, and biology share similar “languages.” Other, less academic genres share a “language” that is not ‘linguistic’ in any ordinary sense. For example, the ‘language’ of facial expressions or of gesture, the ‘language’ of fashion, of clothes, or of traffic lights. Music is a ‘language’, with complex relations between different sounds and chords. When this language represents a meaning for a subject, it becomes a sign.

Saussure divided language into two parts. He called the underlying rule-governed structure of language, which enables us to produce well-formed sentences, the langue (the language system). This consisted of the general rules and codes of the linguistic system, which all its users must share if it is to be of use as a means of communication. The rules are the principles that we learn when we learn a language and they enable us to use language to say whatever we want. For example, in English, the preferred word order is subject-verb-object (‘the cat sat on the mat’), whereas, in Latin, the verb usually comes at the end. For Saussure, the underlying structure of rules and codes (langue) was the social part of language, the part which could be studied with the law-like precision of science because of its closed, limited nature. It was his preference for studying language at this level of its ‘deep structure’ which makes Saussure’s model of language structuralist.

‘La langue is the system of language, the language as a system of forms’ (Culler, 1976, p. 29).

The second part consisted of the particular acts of speaking or writing or drawing, which — using the structure and rules of the langue – are produced by an actual speaker or writer. He called this parole. The second part of language, the individual speech-act or utterance (parole), he regarded as the ‘surface’ of language. There was an infinite number of such possible utterances. Hence, parole inevitably lacked those structural properties — forming a closed and limited set — which would have enabled us to study it ‘scientifically’.

“Parole is actual speech [or writing], the speech acts which are made possible by the language” (Culler, 1976, p. 29)

Perhaps the most important aspect of the sign’s use in language is that the meaning of the sign is always determined differentially. That means that The meaning of the sign is fixed based on the relative meanings of the other signifier/signifier combinations that exist relative to it at a given moment in time. For example, the meaning of “panther” is stabilized, for instance, by signs like “cat,” “lion,” “feline,” and “ocelot.” But it is also stabilized by its relationship to other signs like “Wakanda,” “Fred Hampton,” “Kwame Ture,” and “COINTELPRO.” The meaning of a sign depends on other, related signs. The difference between signs ultimately determines many of the concepts we share in common.

Ultimately, language is a social phenomenon. It cannot be an individual matter because we cannot make up the rules of language individually, for ourselves. Their source lies in society, in the culture, in our shared cultural codes, in the language system – not in nature or in the individual subject.

Metaphor Transfers Meaning between Signs

Metaphor describes a relationship between signs. It fits with our discussion because it supports the constructivist view of representation. We experience reality through the language our shared language community uses. Metaphor is part of our basic capacity to construct this reality. It allows us to focus on certain aspects of reality while avoiding others. And different metaphors can depict and transform the *same* reality, so that two people can look at, read, or hear the same thing and come away with a different interpretation of reality.

The word “metaphor” is older than the theory of the sign and is often attributed to Aristotle, who mentions it explicitly in the Rhetoric. In Greek, it is the composite of meta (over) and phereas (to carry). It can be defined as a figure of speech in which two dissimilar things are said to be similar, offering a new perspective on a known issue. Metaphor provides “perspective” by activating a range of cognitive associations. Metaphors are “Non-literal comparisons in which a word or phrase from one domain of experience is applied to another domain.” Most importantly, they transfer the characteristics of one object (a vehicle) onto a second object (the tenor).

For example, if I were to say “my roommate is a pig!,” pig (sign 2) would be the vehicle because I am attempting to transfer characteristics of ‘pig-ness’ onto them. My roommate is the tenor (sign 1) because they are the literal person, subject, or topic that I am trying to describe.

| Sign 1 | Sign 2 | |

| Signifier |

|

|

| Signified | The concept of a roommate | The concept of a pig |

The social construction aspect of metaphors enters the picture when we habitually or even unconsciously begin to use metaphors that texture our reality. We could think, for instance, of how often we describe social or professional situations in terms of implied violence or hostility, thereby setting the expectation and reflecting the reality that our social and work lives are violent. When life is war, we conceive of aspects of our reality in warlike terms. “They attacked my argument” or “I shot down her point” are ways of imagining oneself as a speech-combatant in which the other person is the enemy. When debates or arguments are battles, then they are framed implicitly as things to be won and lost, rather than spaces for shared understanding. If for instance, we moved to metaphors where arguments were a dance, then this vehicle would allow us to instead imagine ourselves as partners who are practicing for the purposes of collaboration. This is also the direct tie-in to Part 2 of this recording by Dr. Belinda Stillion Southard. Dr. Stillion Southard argues that it is possible to change beliefs by changing language and that the metaphors we use directly guide the values that we support.

An example of an extended metaphor. TW: Strong language

As a final example of metaphor, the above clip displays John Mulaney’s “Horse in the Hospital” sketch. The “horse” is the vehicle for an extended metaphor. Although he doesn’t explicitly name his tenor, you will likely be able to deduce it. As John Mulaney notes at the beginning of the clip, the President represents a larger body of people and values. In other words, the President is a signifier for a shared set of public meanings. Once you’ve watched the clip, let’s turn to Anne Norton’s chapter, “The President as Sign.”

The President as Sign

Norton makes the point that Americans are so extensively wedded to the idea of representation that it would be nearly impossible to think of our culture without the many ways that Americans represent themselves to themselves:

Americans represent themselves in public documents and private letters, diplomas and diaries. In education, institutions, and the mundane practices of everyday life, Americans read and write themselves (as they read and write their nation) into being. This self-conscious being in language does not replace being in the flesh. The constraints of the body are partially evaded, but the needs and desires of the body are enhanced and elaborated in writing and in these written selves. (Anne Norton, “The President as Sign” in Republic of Signs, p.3)

All of these are “signs,” documents, letters, diplomas, diaries, reading, writing, and bodies are sites of representation, of meaning-making. To that end, the president is a very good example of the theory of the ‘sign’ in practice. The President represents a lot: “the nation, the government, the executive branch.” The President is assumed to represent the nation to itself in many ways.

“The embodiment of the presidency enables the President to present an image of the people to itself: singular, united, with a common material form and a single will.” (p. 121)

On the one hand, as the elected “representative” of the people, the President often seems to stand in for the popular will, even if they do not win the popular vote. The character of the President is understood to reflect the character of the voting public. The policies of the President reflect the values of their electors and the vision of the future they would like to see. The President also represents the nation when they engage with other leaders abroad, where they strive to erase the idea that there are many ‘meanings’ competing for attention and publicity in the United States. The fact that the President cannot represent “everything” but must represent “something” is precisely what makes them a sign; their body and individuality act as the material support for a multiplicity of meanings competing for national attention and accountability. That responsibility is, in the words of philosopher Jacques Derrida, both necessary and impossible. It is necessary because governing to benefit the widest population possible. It is impossible because the interests of the population appear to conflict, because the interest of some is to be against governance, or because some interests are refused. That is also why it is so important that the person elected be capable of understanding the obligation of the position to the public.

Using Ronald Reagan and Franklin Delano Roosevelt as examples, Norton demonstrates the “variety of representative strategies made available to Presidents through the interplay of signifier and signified in the sign” (93), and revealing the complex history of personality traits and circumstance that help shape presidential history.

Roosevelt, whose mobility was limited due to polio, took office during the Great Depression. His prominent disability was analogous to the hardship the entire nation faced, and when he spoke of national recovery he could therefore be trusted. When the United States eventually emerged from the Great Depression, Roosevelt garnered comparisons to Lincoln, as the nation’s second savior. The President’s sick body — and his ability to apparently overcome it — was a sign of the nation’s economic sickness, and the chutzpah it would need to overcome it, albeit in a deeply ableist way.

Roosevelt could be recognized as a representative without recourse to that faith in abstractions that the collapse of central economic significations had undermined. The multiple referents Roosevelt entailed as signifier played a crucial role in determining the meaning of his presidency. The nation was economically paralyzed. Roosevelt was paralyzed. But Roosevelt came from a family of great wealth, power, and prestige. He possessed these himself. This apparent contradiction. in Roosevelt as signifier enabled him to simultaneously represent and subvert the image of the nation as paralyzed and impotent. (p.106)

Reagan’s authority and reputation as president in part derived from his career in acting. Though he had not served in actual combat, he had portrayed it on screen, lending credibility to his calls for military action. Reagan’s self-aggrandizing bears resemblance to the boasting of Davy Crockett, frontiersman turned congressman. Reagan’s own boasting alludes to this history of the mythic Westerner, explaining the personal exceptionalism that allowed him to transcend from actor to president. As President, Reagan’s own “personal exceptionalism” became an “American exceptionalism,” an idea that America is beholden to no one and nothing, creating tremendous national debts while rallying his voters in the name of white and evangelical values. Consider the following advertisement, which presents a famous example of “American exceptionalism” as nostalgia for a version of American life which, for many, has never existed:

Reagan’s 1984 “Morning in America” Campaign Advertisement

As Reagan and Roosevelt illustrate, the office of the presidency holds meaning as a result of those who have previously held office, personality traits, and simultaneous political contexts. This is made possible as a result of the president’s visibility to the public, as the president is seen by the public they are able to see themselves reflected in the president “singular, united, with a common material form and a single will” (121). That is why the president is a sign: different versions and visions of a “whole” of the people, the “whole” of the nation.

One of the last points that Norton makes is about Richard Nixon and the way that the Watergate controversy changed the character of the president-as-sign. One of the things that are at least as true today as it was during the Watergate scandal is that the people are subjected to power as a function of sight. As Norton writes,

Those who watched the Watergate hearings saw those who held power brought unwillingly into the public eye. They saw them subjected to the gaze, their actions, their words, their secrets revealed. All who watched participated directly in this exercise of the power of surveillance’ a power they held collectively. Those who watched knew that they watched with their compatriots. They knew that their watching was a sign and an exercise of a power held (as it was then exercised) collectively. The President, the President’s men’ and the congressional committee came under the watching eye of the people.

In the following clip from the film Frost/Nixon, which depicts a famous series of post-presidential interviews with Richard Nixon, you can see how Nixon moves from being the “watcher” to being “the watched”:

Part 2: “Change the Language, Change the Beliefs”

A Lecture by Dr. Belinda Stillion-Southard

This lecture continues the discussion of representation by explaining what kind of work language does and how changing our vocabularies can make tangible differences in our world. Dr. Stillion-Southard is a scholar of American feminist rhetoric in the United States and primarily discusses historical instances of speech that sharply contrast with public and political speech today.

Secondary Readings

- Norton, Anne. “Chapter 3: The President as a Sign.” Republic of signs: Liberal theory and American popular culture. University of Chicago Press, 1993

Additional Resources

- De Saussure, Ferdinand. Course in general linguistics. Columbia University Press, 2011.

- Barthes, Roland. Mythologies: Selected and Translated from the French. Translated by Annette Lavers, Hill and Wang, 1972.

- Culler, Jonathan D. The Pursuit of Signs: Semiotics, Literature, Deconstruction. Cornell University Press, 2002.

- Silverman, Kaja. “Liberty, maternity, commodification.” New Formations 5 (1988): 69-89.