Theme 2: How Does Blood and Organ Donation Work?

2.2 Components of the Blood

The Role of Blood in the Body

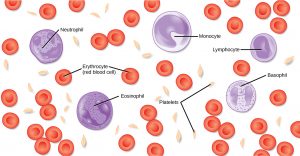

Most of us have suffered a cut or a scraped knee and have seen our own blood. What exactly is blood, and what does it do? Blood, like the human blood illustrated in Figure 1 is important for regulation of the body’s systems and homeostasis. Blood helps maintain the body’s systems in working order by stabilizing pH, temperature, proper amounts of water, salts and nutrients, and by eliminating excess heat. Blood supports growth by distributing nutrients and hormones, and by removing waste. Blood plays a protective role by transporting clotting factors and platelets to prevent blood loss and transporting disease-fighting agents to sites of infection.

Blood is actually a term used to describe the liquid that moves through the vessels and includes plasma (the liquid portion, which contains water, proteins, salts, lipids, and glucose) and the different types of cells found in the plasma. The three main types of cells in human blood are red blood cells, also called erythrocytes, white blood cells, or leukocytes, and platelets, or thrombocytes. Each of these blood components plays specific roles in maintaining the health of the body.

*

Red Blood Cells

Red blood cells, or erythrocytes (erythro- = “red”; -cyte = “cell”), are specialized cells that circulate through the body delivering oxygen to cells; they are formed from stem cells in the bone marrow. In mammals, red blood cells are small biconcave cells that at maturity do not contain a nucleus or mitochondria and are only 7–8 µm in size.

The red coloring of blood comes from the iron-containing protein hemoglobin. The principal job of this protein is to carry oxygen, but it also transports carbon dioxide as well. Hemoglobin is packed into red blood cells at a rate of about 250 million molecules of hemoglobin per cell. Each hemoglobin molecule binds four oxygen molecules so that each red blood cell carries one billion molecules of oxygen. There are approximately 25 trillion red blood cells in the five liters of blood in the human body, which could carry up to 25 sextillion (25 × 1021) molecules of oxygen in the body at any time. In mammals, the lack of organelles in erythrocytes leaves more room for the hemoglobin molecules, and the lack of mitochondria also prevents use of the oxygen for metabolic respiration. Variants of hemoglobin help humans adapt to different environments. For example, Hgb-S causes sickle-cell anemia; although this variant of hemoglobin is not as efficient at transporting O2, it does provide some protection against malaria, thus providing an advantage to heterozygous individuals. Another variant is Hgb-F or fetal hemoglobin, which transports O2 efficiently in the low oxygen conditions found in the developing fetus. Red blood cells develop and mature in the bone marrow.

The small size and large surface area of red blood cells allows for rapid diffusion of oxygen and carbon dioxide across the plasma membrane. In the lungs, carbon dioxide is released and oxygen is taken in by the blood. In the tissues, oxygen is released from the blood and carbon dioxide is bound for transport back to the lungs.

A characteristic of red blood cells is their glycolipid and glycoprotein coating; these are lipids and proteins that have carbohydrate molecules attached. In humans, the surface glycoproteins and glycolipids on red blood cells vary between individuals, producing the different blood types, such as A, B, and O. Red blood cells have an average life span of 120 days, at which time they are broken down. We will take a deeper dive into blood typing, antigens, and antibodies when we explore the immune system in a later section, and we also will learn that white blood cells play important roles in immunity.

*

White Blood Cells

White blood cells, also called leukocytes (leuko = white), make up approximately one percent by volume of the cells in blood. The role of white blood cells is very different than that of red blood cells: they are primarily involved in the immune response to identify and target pathogens, such as invading bacteria, viruses, and other foreign organisms. White blood cells are formed continually; some only live for hours or days, but some live for years.

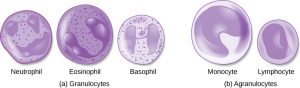

The morphology of white blood cells differs significantly from red blood cells. They have nuclei and do not contain hemoglobin. The different types of white blood cells are identified by their microscopic appearance after histologic staining, and each has a different specialized function. The two main groups, both illustrated in Figure 2 are the granulocytes, which include the neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils, and the agranulocytes, which include the monocytes and lymphocytes.

Granulocytes contain granules in their cytoplasm; the agranulocytes are so named because of the lack of granules in their cytoplasm. While they are named based on their appearances, each type of white blood cell also has unique functions. We will discuss the different types of leukocytes and their functions in a later section of this book.

Platelets and Coagulation Factors

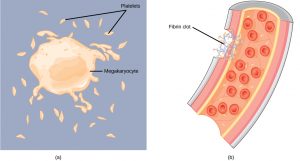

Blood must clot to heal wounds and prevent excess blood loss. Small cell fragments called platelets (thrombocytes) are attracted to the wound site where they adhere by extending many projections and releasing their contents. These contents activate other platelets and also interact with other coagulation factors, which convert fibrinogen, a water-soluble protein present in blood serum into fibrin (a non-water soluble protein), causing the blood to clot. Many of the clotting factors require vitamin K to work, and vitamin K deficiency can lead to problems with blood clotting. Many platelets converge and stick together at the wound site forming a platelet plug (also called a fibrin clot), as illustrated in Figure 3b. The plug or clot lasts for a number of days and stops the loss of blood. Platelets are formed from the disintegration of larger cells called megakaryocytes, like that shown in Figure 3a. For each megakaryocyte, 2000–3000 platelets are formed with 150,000 to 400,000 platelets present in each cubic millimeter of blood. Each platelet is disc shaped and 2–4 μm in diameter. They contain many small vesicles but do not contain a nucleus.

*

Plasma and Serum

The liquid component of blood is called plasma, and it is separated by spinning or centrifuging the blood at high rotations (3000 rpm or higher). The blood cells and platelets are separated by centrifugal forces to the bottom of a specimen tube. The upper liquid layer, the plasma, consists of 90 percent water along with dissolved substances, including the coagulation factors mentioned above.

The plasma component of blood without the coagulation factors is called the serum. Serum is similar to the fluid surrounding the cells in other tissues ,and contains precise concentrations of important ions like calcium and sodium necessary for cellular functions. Other components in the serum include proteins that assist with maintaining pH and water balance while giving viscosity to the blood. The serum also contains antibodies, specialized proteins that are important for defense against viruses and bacteria. Lipids, including cholesterol, are also transported in the serum, along with various other substances including nutrients, hormones, metabolic waste, plus external substances, such as, drugs, viruses, and bacteria.

Human serum albumin is the most abundant protein in human blood plasma and is synthesized in the liver. Albumin, which constitutes about half of the blood serum protein, transports hormones and fatty acids, buffers pH, and maintains water balance in the body.

Blood Types Related to Proteins on the Surface of the Red Blood Cells

Red blood cells are coated in antigens made of glycolipids and glycoproteins. The composition of these molecules is determined by genetics, which have evolved over time. In humans, the different surface antigens are grouped into 24 different blood groups with more than 100 different antigens on each red blood cell. The two most well known blood groups are the ABO, shown in Figure 4, and Rh systems. The surface antigens in the ABO blood group are glycolipids, called antigen A and antigen B. People with blood type A have antigen A, those with blood type B have antigen B, those with blood type AB have both antigens, and people with blood type O have neither antigen. Antibodies called agglutinogens are found in the blood plasma and react with the A or B antigens, if the two are mixed. When type A and type B blood are combined, agglutination (clumping) of the blood occurs because of antibodies in the plasma that bind with the opposing antigen; this causes clots that coagulate in the kidney causing kidney failure. Type O blood has neither A or B antigens, and therefore, type O blood can be given to all blood types. Type O negative blood is the universal donor. Type AB positive blood is the universal acceptor because it has both A and B antigen. The ABO blood groups were discovered in 1900 and 1901 by Karl Landsteiner at the University of Vienna.

The Rh blood group was first discovered in Rhesus monkeys. Most people have the Rh antigen (Rh+) and do not have anti-Rh antibodies in their blood. The few people who do not have the Rh antigen and are Rh– can develop anti-Rh antibodies if exposed to Rh+ blood. This can happen after a blood transfusion or after an Rh– woman has an Rh+ baby. The first exposure does not usually cause a reaction; however, at the second exposure, enough antibodies have built up in the blood to produce a reaction that causes agglutination and breakdown of red blood cells. An injection can prevent this reaction.

Link to Learning

*

Section Summary

Specific components of the blood include red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, and the plasma, which contains coagulation factors and serum. Blood is important for regulation of the body’s pH, temperature, osmotic pressure, the circulation of nutrients and removal of waste, the distribution of hormones from endocrine glands, and the elimination of excess heat; it also contains components for blood clotting. Red blood cells are specialized cells that contain hemoglobin and circulate through the body delivering oxygen to cells. White blood cells are involved in the immune response to identify and target invading bacteria, viruses, and other foreign organisms; they also recycle waste components, such as old red blood cells. Platelets and blood clotting factors cause the change of the soluble protein fibrinogen to the insoluble protein fibrin at a wound site forming a plug. Plasma consists of 90 percent water along with various substances, such as coagulation factors and antibodies. The serum is the plasma component of the blood without the coagulation factors.

*

Glossary

- plasma

- liquid component of blood that is left after the cells are removed

- platelet

- (also, thrombocyte) small cellular fragment that collects at wounds, cross-reacts with clotting factors, and forms a plug to prevent blood loss

- red blood cell

- small (7–8 μm) biconcave cell without mitochondria (and in mammals without nuclei) that is packed with hemoglobin, giving the cell its red color; transports oxygen through the body

- serum

- plasma without the coagulation factors

- white blood cell

- large (30 μm) cell with nuclei of which there are many types with different roles including the protection of the body from viruses and bacteria, and cleaning up dead cells and other waste