Theme 1: What Makes Us Unique?

1.6 How Phylogenies are Made

Scientists must collect accurate information that allows them to make evolutionary connections among organisms. Similar to detective work, scientists must use evidence to uncover the facts. In the case of phylogeny, evolutionary investigations focus on two types of evidence: morphologic (form and function) and genetic.

*

Two Options for Similarities

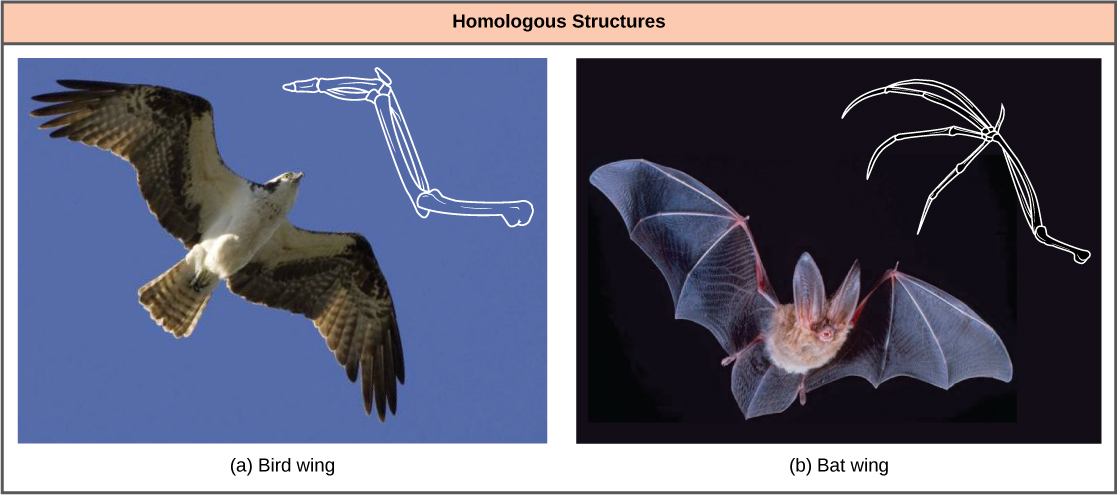

In general, organisms that share similar physical features and genomes are more closely related than those that do not. We refer to such features that overlap both morphologically (in form) and genetically as homologous structures. They stem from developmental similarities that are based on evolution. For example, the bones in bat and bird wings have homologous structures (Figure 1).

Notice it is not simply a single bone, but rather a grouping of several bones arranged in a similar way. The more complex the feature, the more likely any kind of overlap is due to a common evolutionary past. Imagine two people from different countries both inventing a car with all the same parts and in exactly the same arrangement without any previous or shared knowledge. That outcome would be highly improbable. However, if two people both invented a hammer, we can reasonably conclude that both could have the original idea without the help of the other. The same relationship between complexity and shared evolutionary history is true for homologous structures in organisms.

Misleading Appearances

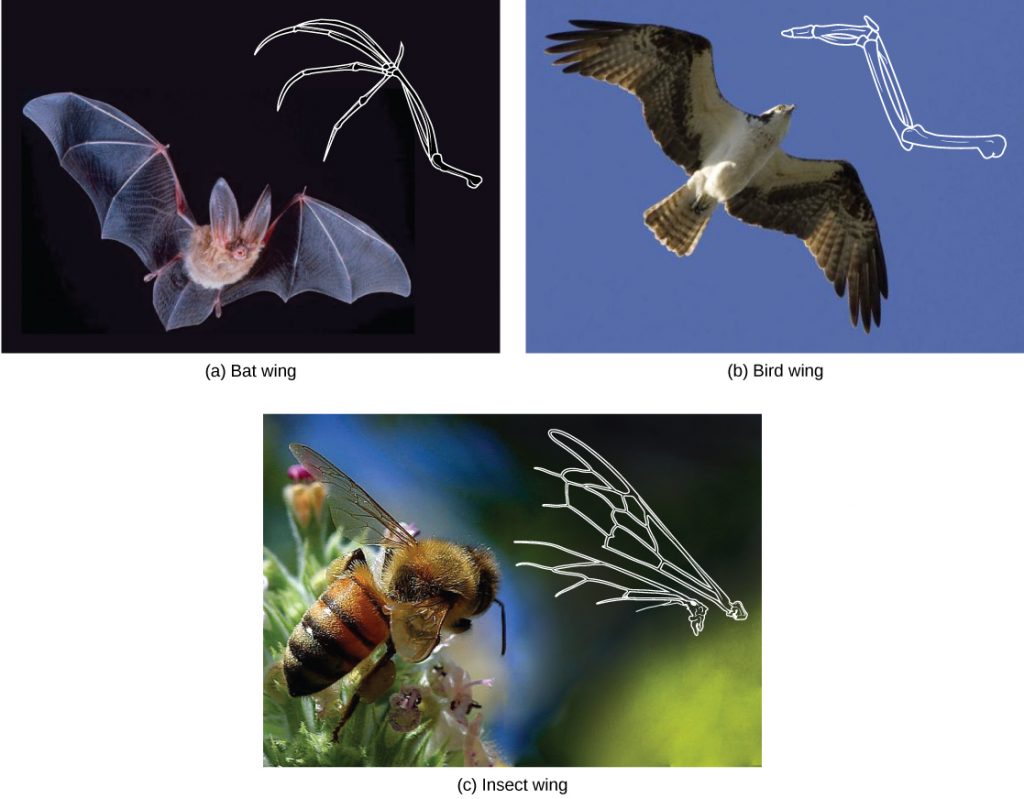

Some organisms may be very closely related, even though a minor genetic change caused a major morphological difference to make them look quite different. Similarly, unrelated organisms may be distantly related, but appear very much alike. This usually happens because both organisms were in common adaptations that evolved within similar environmental conditions. When similar characteristics occur because of environmental constraints and not due to a close evolutionary relationship, it is an analogy or homoplasy. For example, insects use wings to fly like bats and birds, but the wing structure and embryonic origin is completely different. These are analogous structures (Figure 2).

Similar traits can be either homologous or analogous. Homologous structures share a similar embryonic origin. Analogous organs have a similar function. For example, the bones in a whale’s front flipper are homologous to the bones in the human arm. These structures are not analogous. A butterfly or bird’s wings are analogous but not homologous. Some structures are both analogous and homologous: bird and bat wings are both homologous and analogous. Scientists must determine which type of similarity a feature exhibits to decipher the organisms’ phylogeny.

Molecular Comparisons

The advancement of DNA technology has given rise to molecular systematics, which is use of molecular data in taxonomy and biological geography (biogeography). New computer programs not only confirm many earlier classified organisms, but also uncover previously made errors. As with physical characteristics, even the DNA sequence can be tricky to read in some cases. For some situations, two very closely related organisms can appear unrelated if a mutation occurred that caused a shift in the genetic code. Inserting or deleting a mutation would move each nucleotide base over one place, causing two similar codes to appear unrelated.

Sometimes two segments of DNA code in distantly related organisms randomly share a high percentage of bases in the same locations, causing these organisms to appear closely related when they are not. For both of these situations, computer technologies help identify the actual relationships, and, ultimately, the coupled use of both morphologic and molecular information is more effective in determining phylogeny.

Why Does Phylogeny Matter? Evolutionary biologists could list many reasons why understanding phylogeny is important to everyday life in human society. For botanists, phylogeny acts as a guide to discovering new plants that can be used to benefit people. Think of all the ways humans use plants—food, medicine, and clothing are a few examples. If a plant contains a compound that is effective in treating cancer, scientists might want to examine all of the compounds for other useful drugs.

A research team in China identified a DNA segment that they thought to be common to some medicinal plants in the family Fabaceae (the legume family). They worked to identify which species had this segment (Figure 3). After testing plant species in this family, the team found a DNA marker (a known location on a chromosome that enabled them to identify the species) present. Then, using the DNA to uncover phylogenetic relationships, the team could identify whether a newly discovered plant was in this family and assess its potential medicinal properties.

*

Building Phylogenetic Trees

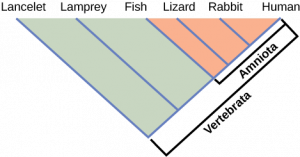

How do scientists construct phylogenetic trees? After they sort the homologous and analogous traits, scientists often organize the homologous traits using cladistics. This system sorts organisms into clades: groups of organisms that descended from a single ancestor. For example, in Figure 4, all the organisms in the orange region evolved from a single ancestor that had amniotic eggs. Consequently, these organisms also have amniotic eggs and make a single clade, or a monophyletic group. Clades must include all descendants from a branch point.

Which animals in this figure belong to a clade that includes animals with hair? Which evolved first, hair or the amniotic egg?

Shared Traits

Organisms evolve from common ancestors and then diversify. Scientists use the phrase “descent with modification” because even though related organisms have many of the same characteristics and genetic codes, changes occur. This pattern repeats as one goes through the phylogenetic tree of life:

- A change in an organism’s genetic makeup leads to a new trait which becomes prevalent in the group.

- Many organisms descend from this point and have this trait.

- New variations continue to arise: some are adaptive and persist, leading to new traits.

- With new traits, a new branch point is determined (go back to step 1 and repeat).

The tricky aspect to shared ancestral and shared derived traits is that these terms are relative. We can consider the same trait one or the other depending on the particular diagram that we use. Returning to Figure 4, note that the amniotic egg is a shared ancestral character for the Amniota clade, while having hair is a shared derived character for some organisms in this group. These terms help scientists distinguish between clades in building phylogenetic trees.

Choosing the Right Relationships

To aid in the tremendous task of describing phylogenies accurately, scientists often use the concept of maximum parsimony, which means that events occurred in the simplest, most obvious way. For example, if a group of people entered a forest preserve to hike, based on the principle of maximum parsimony, one could predict that most would hike on established trails rather than forge new ones.

For scientists deciphering evolutionary pathways, the same idea is used: the pathway of evolution probably includes the fewest major events that coincide with the evidence at hand. Starting with all of the homologous traits in a group of organisms, scientists look for the most obvious and simple order of evolutionary events that led to the occurrence of those traits.

*

Section Summary

To build phylogenetic trees, scientists must collect accurate information that allows them to make evolutionary connections between organisms. Using morphologic and molecular data, scientists work to identify homologous characteristics and genes. Similarities between organisms can stem either from shared evolutionary history (homologies) or from separate evolutionary paths (analogies). Scientists can use newer technologies to help distinguish homologies from analogies. After identifying homologous information, scientists use cladistics to organize these events as a means to determine an evolutionary timeline. They then apply the concept of maximum parsimony, which states that the order of events probably occurred in the most obvious and simple way with the least amount of steps. For evolutionary events, this would be the path with the least number of major divergences that correlate with the evidence.

*

Glossary

- analogy

- (also, homoplasy) characteristic that is similar between organisms by convergent evolution, not due to the same evolutionary path

- cladistics

- system to organize homologous traits to describe phylogenies

- maximum parsimony

- applying the simplest, most obvious way with the least number of steps

- molecular systematics

- technique using molecular evidence to identify phylogenetic relationships

- monophyletic group

- (also, clade) organisms that share a single ancestor

- shared ancestral trait

- describes a characteristic on a phylogenetic tree that all organisms on the tree share

- shared derived trait

- describes a characteristic on a phylogenetic tree that only a certain clade of organisms share