9.2 The Selection of a Cost Flow Assumption for Reporting Purposes

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Appreciate that reported inventory and cost of goods sold numbers are not intended to be right or wrong but rather must conform to U.S. GAAP, which includes several different allowable cost flow assumptions.

- Recognize that three cost flow assumptions (FIFO, LIFO, and averaging) are particularly popular in the United States.

- Understand the meaning of the LIFO conformity rule and realize that use of LIFO in the U.S. largely stems from the presence of this tax rule.

- Know that U.S. companies prepare financial statements according to U.S. GAAP and their income tax returns based on the Internal Revenue Code so that significant differences often exist.

Question: FIFO, LIFO, and averaging can present radically different portraits of identical events. Is the gross profit for this men’s clothing store really $60 (FIFO), $40 (LIFO), or $50 (averaging) in connection with the sale of one blue shirt? Analyzing the numbers presented by most companies can be difficult if not impossible without understanding the implications of the assumption applied. Which of the cost flow assumptions is viewed as most appropriate in producing fairly presented financial statements?

Answer: Because specific identification reclassifies the cost of the actual unit that was sold, finding theoretical fault with that approach is difficult. Unfortunately, specific identification is nearly impossible to apply unless easily distinguishable differences exist between similar inventory items. That leaves FIFO, LIFO, and averaging. Arguments over both their merits and problems have raged for decades. Ultimately, the numbers in financial statements must be presented fairly based on the cost flow assumption that is applied.

In Chapter 6 “Why Should Decision Makers Trust Financial Statements?”, an important distinction was made. The report of the independent auditor never assures decision makers that financial statements are “presented fairly.” That is a hopelessly abstract concept like truth and beauty. Instead, the auditor states that the statements are “presented fairly…in conformity with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America.” That is a substantially more objective standard. Thus, for this men’s clothing store, all the following figures are presented fairly but only in conformity with the cost flow assumption used by the reporting company.

Question: Since company officials are allowed to select a cost flow assumption, which of these methods is most typically found in the reporting of companies in the United States?

Answer: To help interested parties gauge the usage of various accounting principles, a survey is carried out annually of the financial statements of six hundred large companies in this country. The resulting information allows accountants, auditors, and decision makers to weigh the validity of a particular method or presentation. For 2007, that survey found the following frequency of application of cost flow assumptions. Some companies use multiple assumptions: one for a particular part of inventory and a different one for the remainder. Thus, the total here is well above six hundred even though over one hundred of the surveyed companies did not have inventory or mention a cost flow assumption (inventory was probably an immaterial amount). As will be discussed a bit later in this chapter, using multiple assumptions is especially common when a U.S. company has subsidiaries located internationally.

| Inventory Cost Flow Assumptions—600 Companies Surveyed (Iofe & Calderisi, 2008) | |

|---|---|

| First-in, First-out (FIFO) | 391 |

| Last-in, First-out (LIFO) | 213 |

| Averaging | 155 |

| Other | 24 |

Interestingly, individual cost flow assumptions tend to be more prevalent in certain industries. In this same survey, 86 percent of the financial statements issued by food and drug stores used LIFO whereas only 10 percent of the companies labeled as “computers, office equipment” had adopted this same approach. That difference could quite possibly be caused by the presence of inflation or deflation. Prices of food and drugs tend to escalate consistently over time while computer prices often fall as technology advances

Question: In periods of inflation, as demonstrated by the previous example, FIFO reports a higher gross profit (and, hence, net income) and a higher inventory balance than does LIFO. Averaging presents figures that normally fall between these two extremes. Such results are widely expected by those readers of financial statements who understand the impact of the various cost flow assumptions.

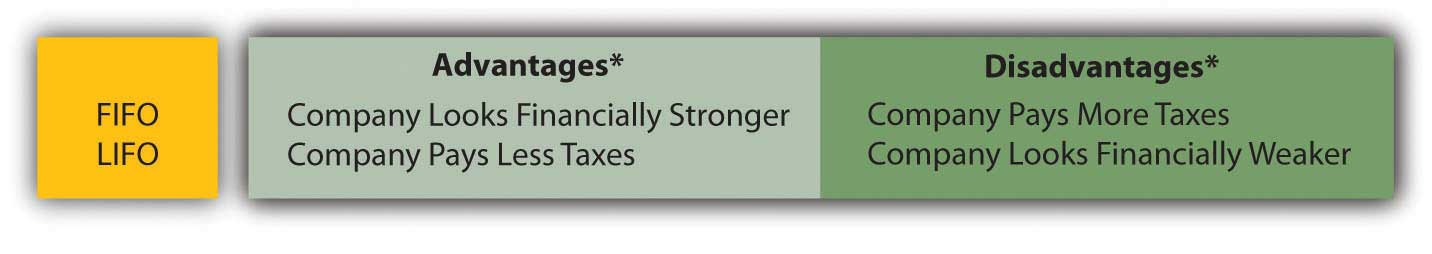

Any one of these methods is permitted for financial reporting. Why is FIFO not the obvious choice for every organization that anticipates inflation in its inventory costs? Officials must prefer to report figures that make the company look stronger and more profitable. With every rise in prices, FIFO shows a higher income because the earlier (cheaper) costs are transferred to cost of goods sold. Likewise, FIFO reports a higher total inventory on the balance sheet because the later (higher) cost figures are retained in the inventory T-account. The company is no different physically by this decision but FIFO makes it look better. Why does any company voluntarily choose LIFO, an approach that reduces reported income and total assets when prices rise?

Answer: LIFO might well have faded into oblivion because of its negative impact on key reported figures (during inflationary periods) except for a U.S. income tax requirement known as the LIFO conformity rule. Although this tax regulation is not part of U.S. GAAP and looks rather innocuous, it has a huge impact on the way inventory and cost of goods sold are reported to decision makers in this country.

As prices rise, companies prefer to apply LIFO for tax purposes because this assumption reduces reported income and, hence, required cash payments to the government. In the United States, LIFO has come to be universally equated with the saving of tax dollars. When LIFO was first proposed as a tax method in the 1930s, the United States Treasury Department appointed a panel of three experts to consider its validity. The members of this group were split over a final resolution. They eventually agreed to recommend that LIFO be allowed for income tax purposes but only if the company was also willing to use LIFO for financial reporting. At that point, tax rules bled over into U.S. GAAP.

The rationale behind this compromise was that companies were allowed the option but probably would not choose LIFO for their tax returns because of the potential negative effect on figures reported to investors, creditors, and others. During inflationary periods, companies that apply LIFO do not look as financially healthy as those that adopt FIFO. Eventually this recommendation was put into law and the LIFO conformity rule was born. If LIFO is used on a company’s income tax return, it must also be applied on the financial statements.

However, as the previous statistics point out, this requirement did not prove to be the deterrent that was anticipated. Actual use of LIFO has become quite popular. For many companies, the savings in income tax dollars more than outweigh the problem of having to report numbers that make the company look a bit weaker. That is a choice that company officials must make.

Exercise

Link to multiple-choice question for practice purposes: http://www.quia.com/quiz/2092924.html

Question: The LIFO conformity rule requires companies that apply LIFO for income tax purposes to also use that same method for their financial reporting to investors, creditors, and other decision makers. Is the information submitted to the government for income tax purposes not always the same as that presented to decision makers in a set of financial statements? Reporting different numbers seems unethical.

Answer: In jokes and in editorials, companies are often derisively accused of “keeping two sets of books.” The implication is that one is skewed toward making the company look good (for reporting purposes) whereas the other makes the company look bad (for taxation purposes). However, the existence of separate records is a practical necessity. One set is kept based on applicable tax laws while the other enables the company to prepare its financial statements according to U.S. GAAP. Different rules mean that different numbers result.

In filing income taxes with the United States government, a company must follow the regulations of the Internal Revenue Code1. Those laws have several underlying objectives that influence their development.

First, they are designed to raise money for the operation of the federal government. Without adequate funding, the government could not provide hospitals, build roads, maintain a military and the like.

Second, income tax laws enable the government to help regulate the health of the economy. Simply by raising or lowering tax rates, the government can take money out of the economy (and slow public spending) or leave money in the economy (and increase public spending). As an illustration, recently a significant tax break was passed by Congress for first-time home buyers. This move was designed to stimulate the housing market by encouraging additional individuals to consider making a purchase.

Third, income tax laws enable the government to assist certain members of society who are viewed as deserving help. For example, taxpayers who encounter high medical costs or casualty losses are entitled to a tax break. Donations conveyed to an approved charity can also reduce a taxpayer’s tax bill. The rules and regulations were designed to provide assistance for specified needs.

In contrast, financial reporting for decision makers must abide by the guidance of U.S. GAAP, which seeks to set rules for the fair presentation of accounting information. That is the reason U.S. GAAP exists. Because the goals are entirely different, there is no particular reason for the resulting financial statements to correspond to the tax figures submitted to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Not surprisingly, though, significant overlap is found between tax laws and U.S. GAAP. For example, both normally recognize the cash sale of merchandise as revenue at the time of sale. However, countless differences do exist between the two sets of rules. Depreciation, as just one example, is computed in an entirely different manner for tax purposes than for financial reporting.

Although separately developed, financial statements and income tax returns are tied together at one significant spot: the LIFO conformity rule. If a company chooses to use LIFO for tax purposes, it must do the same for financial reporting. Without that requirement, many companies likely would use FIFO in creating their financial statements and LIFO for their income tax returns. Much of the popularity shown earlier for LIFO is undoubtedly derived from this tax requirement rather than any theoretical merit.

Key Takeaways

Information found in financial statements is required to be presented fairly in conformity with U.S. GAAP. Because several inventory cost flow assumptions are allowed, presented numbers can vary significantly from one company to another and still be appropriate. FIFO, LIFO, and averaging are all popular. Understanding and comparing financial statements is quite difficult without knowing the implications of the method selected. LIFO, for example, tends to produce low-income figures in a period of inflation. This assumption probably would not be used extensively except for the LIFO conformity rule that prohibits its use for tax purposes unless also reported on the company’s financial statements. Typically, financial reporting and the preparation of income tax returns are unrelated because two sets of rules are used with radically differing objectives. However, the LIFO conformity rule joins these two at this one key spot.

1Many states also charge a tax on income. These states have their own unique set of laws although they often resemble the tax laws applied by the federal government.

References

Iofe, Y., senior editor, and Matthew C. Calderisi, CPA, managing editor, Accounting Trends & Techniques, 62nd edition (New York: American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, 2008), 159.