5.3 Preparing Financial Statements Based on Adjusted Balances

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Explain the need for an adjusting entry in the reporting of unearned revenue and be able to prepare that adjustment.

- Prepare an income statement, statement of retained earnings, and balance sheet based on the balances in an adjusted trial balance.

- Explain the purpose and construction of closing entries.

The last adjusting entry to be covered at this time is unearned (or deferred) revenue. Some companies operate in industries where money is received first and then earned gradually over time. Newspaper and magazine businesses, for example, are paid in advance by their subscribers and advertisers. The earning process becomes substantially complete by the subsequent issuance of their products. Thus, the December 28, 2008, balance sheet for the New York Times Company reported a liability titled “unexpired subscriptions” of $81 million. This balance represents payments collected from customers who have not yet received their newspapers.

Question: In Journal Entry 13 in Chapter 4 “How Does an Organization Accumulate and Organize the Information Necessary to Prepare Financial Statements? “, the Lawndale Company reported receiving $3,000 for services to be rendered at a later date. An unearned revenue account was recorded as a liability for that amount and appears in the trial balance in Figure 5.1 “Updated Trial Balance”. When is an adjusting entry needed in connection with the recognition of previously unearned revenue?

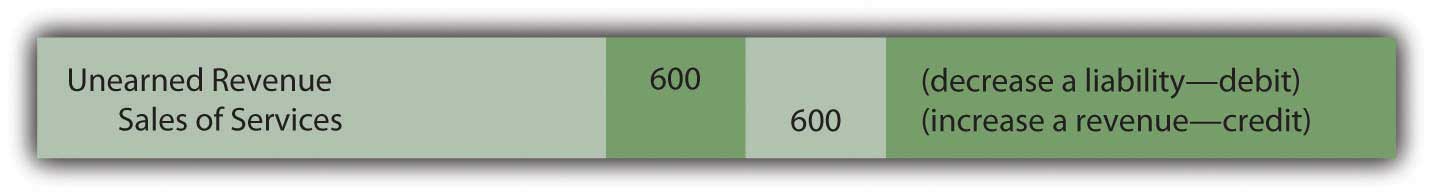

Answer: As indicated, unearned revenue represents a liability recognized when money is received before work is done. After any portion of the required service is carried out so that the earning process is substantially complete, an appropriate amount is reclassified from unearned revenue on the balance sheet to revenue on the income statement. For example, in connection with the $3,000 payment collected by Lawndale, assume that all the work necessary to recognize the first $600 has now been performed. To fairly present this information, an adjusting entry is prepared to reduce the liability and recognize the earned revenue.

Exercise

Link to multiple-choice question for practice purposes: http://www.quia.com/quiz/2092631.html

Question: After all adjusting entries have been recorded in the journal and posted to the appropriate T-accounts in the ledger, what happens next in the accounting process?

Answer: At this point, the accountant believes that all account balances are fairly presented because no material misstatements exist according to U.S. GAAP. As one final check, an adjusted trial balance is produced for a last, careful review. Assuming that no additional concerns are noticed, the accountant prepares an income statement, a statement of retained earnings, and a balance sheet.

The basic financial statements are then completed by the production of a statement of cash flows. In contrast to the previous three, this remaining statement does not report ending ledger account balances but rather discloses the various changes occurring during the period in the composition of the cash account. As indicated in Chapter 3 “In What Form Is Financial Information Actually Delivered to Decision Makers Such as Investors and Creditors?”, all cash flows are classified as resulting from operating activities, investing activities, or financing activities.

The reporting process is then completed by the preparation of the explanatory notes that always accompany a set of financial statements.

The final trial balance for the Lawndale Company (including the four adjusting entries produced above) is presented in the appendix to this chapter. After that, each of the individual figures is appropriately placed within the first three financial statements. Revenues and expenses appear in the income statement, assets and liabilities in the balance sheet, and so on. The resulting statements are also exhibited in the appendix for illustrative purposes. No attempt has been made here to record all possible adjusting entries. For example, no income taxes have been recognized and interest expense has not been accrued in connection with notes payable. Depreciation expense of noncurrent assets with finite lives (the truck, in the company’s trial balance) will be discussed in detail in a later chapter. However, these illustrations are sufficient to demonstrate the end result of the accounting process as well as the basic structure used for the income statement, statement of retained earnings, and balance sheet.

The statement of cash flows for the Lawndale Company cannot be created based solely on the limited information available in this chapter concerning the cash account. Thus, it has been omitted. Complete coverage of the preparation of a statement of cash flows will be presented in Chapter 17 “In a Set of Financial Statements, What Information Is Conveyed by the Statement of Cash Flows?” of this textbook.

Question: Analyze, record, adjust, and report—the four basic steps in the accounting process. Is the work year complete for the accountant after financial statements are prepared?

Answer: One last mechanical process needs to be mentioned. Whether a company is as big as Microsoft or as small as the local convenience store, the final action performed each year by the accountant is the preparation of closing entries. Several types of accounts—specifically, revenues, expenses, gains, losses, and dividends paid—reflect the various changes that occur in a company’s net assets but just for the current period. In order for the accounting system to start measuring the effects for each new year, all of these specific T-accounts must be returned to a zero balance after the annual financial statements are produced.

- Final credit totals existing in every revenue and gain account are closed out by recording equal and off-setting debits.

- Similarly, ending debit balances for expenses, losses, and dividends paid require a credit entry of the same amount to return each of these T-accounts to a zero balance.

After these “temporary” accounts are closed at year’s end, the resulting single figure is the equivalent of the net income reported for the year less dividends paid. This net effect is recorded in the retained earnings T-account. The closing process effectively moves the balance for each revenue, expense, gain, loss, and dividend paid into retained earnings. In the same manner as journal entries and adjusting entries, closing entries are recorded initially in the company’s journal and then posted to the ledger. As a result, the beginning retained earnings balance for the year is updated to arrive at the ending total reported on the balance sheet.

Assets, liabilities, capital stock, and retained earnings all start out each year with a balance that is the same as the ending figure reported on the previous balance sheet. Those accounts are not designed to report an impact occurring just during the current year. In contrast, revenues, expenses, gains, losses, and dividends paid all begin the first day of each year with a zero balance—ready to record the events of this new period.

Key Takeaway

Companies occasionally receive money for services or goods before they are provided. In such cases, an unearned revenue is recorded as a liability to indicate the company’s obligation to its customer. Over time, as the earning process becomes substantially complete, the unearned revenue is reclassified as a revenue through adjusting entries. After this adjustment and all others are prepared and recorded, an adjusted trial balance is created and those figures are then used to produce financial statements. Finally, closing entries are prepared for all revenues, expenses, gains, losses, and dividends paid. Through this process, all of these T-accounts are returned to zero balances so that recording for the new year can begin. The various amounts in these temporary accounts are moved to retained earnings. Thus, its beginning balance for the year is increased to equal the ending total reported on the company’s balance sheet.

Talking with a Real Investing Pro (Continued)

Following is a continuation of our interview with Kevin G. Burns.

Question: Large companies have millions of transactions to analyze, classify, and record so that they can produce financial statements. That has to be a relatively expensive process that produces no income for the company. From your experience in analyzing companies and their financial statements, do you think companies should spend more money on their accounting systems or would they be wise to spend less and save their resources?

Kevin Burns: Given the situations of the last decade ranging from the accounting scandals of Enron and WorldCom to recent troubles in the major investment banks, the credibility of financial statements and financial officers has eroded significantly. My view is that—particularly today—transparency is absolutely paramount and the more detail the better. Along those lines, I think any amounts spent by corporate officials to increase transparency in their financial reporting, and therefore improve investor confidence, is money well spent.

Video Clip

Unnamed Author talks about the five most important points in Chapter 5 “Why Must Financial Information Be Adjusted Prior to the Production of Financial Statements?”.