15.3 Recognition of Deferred Income Taxes

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Understand that the recognition of revenues and expenses under U.S. GAAP differs at many critical points from the rules established by the Internal Revenue Code.

- Explain the desire by corporate officials to defer the payment of income taxes.

- Determine the timing for the reporting of a deferred income tax liability and explain the connection to the matching principle.

- Calculate taxable income when the installment sales method is used as well as the related deferred income tax liability.

Question: At the beginning of this chapter, mention was made that Southwest Airlines reported deferred income taxes at the end of 2008 as a noncurrent liability of $1.9 billion. Such an account balance is not unusual. The Kroger Co. listed a similar $384 million debt on its January 31, 2009, balance sheet. At approximately the same time, Ford Motor Company reported a $614 million

deferred tax liability

for its automotive business and another $3.28 billion for its financial services division. What is the meaning of these accounts?

How is a deferred income tax liability created?

Answer: The reporting of deferred income tax liabilities is, indeed, quite prevalent. One survey in 2007 found that approximately 70 percent of businesses included a deferred tax balance within their noncurrent liabilities (Iofe & Calderisi, 2008). Decision makers need to have a basic understanding of any account that is so commonly encountered in a set of financial statements.

In the discussion of LIFO presented in Chapter 9 “Why Does a Company Need a Cost Flow Assumption in Reporting Inventory?”, the point was made that financial accounting principles and income tax rules are not identical. In the United States, financial information is presented based on the requirements of U.S. GAAP while income tax figures are determined according to the Internal Revenue Code. At many places, these two sets of guidelines converge. For example, if a grocery store sells a can of tuna fish for $6 in cash, the revenue is $6 on both the reported financial statements and the income tax return. However, at a number of critical junctures, the recognized amounts can be quite different.

Where legal, companies frequently exploit these differences for their own benefit by delaying tax payments. The deferral of income taxes is usually considered a wise business strategy because it allows the company to use its cash for a longer period of time and, hence, generate additional revenues. If an entity makes a 10 percent return on its assets and manages to defer a tax payment of $100 million for one year, the additional profit to be earned is $10 million ($100 million × 10 percent).

Businesses commonly attempt to reduce current taxable income by moving it into the future. In general, this is the likely method used by Southwest, Kroger, and Ford to create their deferred tax liabilities.

- Revenue or a gain might be recognized this year for financial reporting purposes but put off until an upcoming time period for tax purposes. The payment of tax on this income has been pushed to a future year.

- An expense is recognized immediately for tax purposes although it can only be deducted in later years according to financial accounting rules.

In both of these cases, taxable income is reduced in the current period (revenue is moved out or expense is moved in) but increased at a later time (revenue is moved in or expense is moved out). Because a larger tax will have to be paid in the subsequent period, a deferred income tax liability is reported.

Deferred income tax liabilities are easiest to understand conceptually by looking at revenues and gains. Assume that a business reports revenue of $100 on its Year One income statement. Because of certain tax rules and regulations, assume that this amount will not be subject to income taxation until Year Six. The $100 is referred to as a temporary tax difference. It is reported for both financial accounting and tax purposes but in two different time periods.

If the effective tax rate is 40 percent, the business records a $40 ($100 × 40 percent) deferred income tax liability on its December 31, Year One, balance sheet. This amount will be paid to the government but not until Year Six when the revenue becomes taxable. The revenue is recognized now according to U.S. GAAP but in a later year for income tax return purposes. Net income is higher in the current year than taxable income, but taxable income will be higher by $100 in the future. Payment of the $40 in income taxes on that $100 difference is delayed until Year Six.

Simply put, a deferred income tax liability1 is created when an event occurs now that will lead to a higher amount of income tax payment in the future.

Exercise

Link to multiple-choice question for practice purposes: http://www.quia.com/quiz/2093032.html

Question: Deferring the payment of an income tax liability does not save a company any money. This process merely delays recognition for tax purposes until a later period. Payment is put off for one or more years. If no tax money is saved, why do companies seek to create deferred income tax liabilities? Why not just pay the income tax now and get it over with?

Answer: As discussed above, delaying the mailing of an income tax check to the government allows a company to make use of its money for a longer period of time. When the cash is paid, it is gone and provides no further benefit to the company. As long as the money is still held, it can be used by management to buy inventory, acquire securities, pay for advertising, invest in research and development activities, and the like. Thus, a common business strategy is to avoid paying taxes for as long as legally possible so that more income can be generated from these funds before they are turned over to the government.

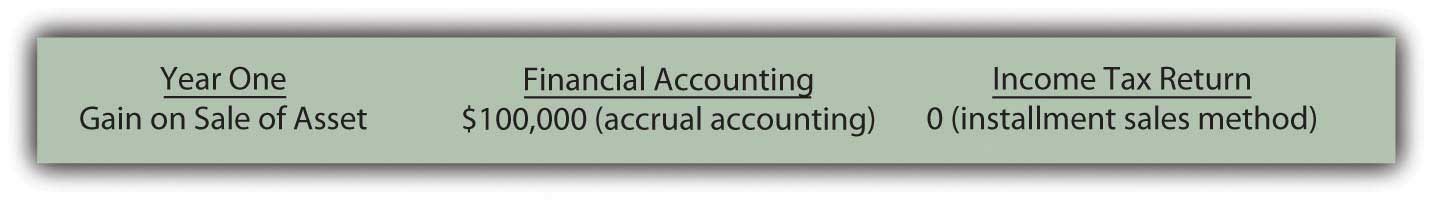

Question: Assume that the Hill Company buys an asset (land, for example) for $150,000. Later, this asset is sold for $250,000 in Year One. The earning process is substantially complete at that point so Hill reports a gain on its Year One income statement of $100,000 ($250,000 less $150,000). Because of the terms of the sales contract, the money will not be collected from the buyer until Year Four (20 percent) and Year Five (80 percent). The buyer is financially strong and expected to pay at the required times. Hill’s effective tax rate for this transaction is 30 percent.

Officials for Hill are pleased to recognize the $100,000 gain on this sale in Year One because it makes the company looks better. However, they prefer to wait as long as possible to pay the income tax especially since no cash has yet been collected from the buyer. How can the recognition of income be deferred for tax purposes so that a deferred income tax liability is reported?

Answer: According to U.S. GAAP, this $100,000 gain is recognized in Year One based on accrual accounting. The earning process is substantially complete and the amount to be collected can be reasonably estimated. However, if certain conditions are met, income tax laws permit taxpayers to report such gains using the installment sales method2. In simple terms, the installment sales method allows a seller to delay the reporting of a gain until cash is collected. The gain is recognized proportionally based on the amount of cash received. If 20 percent is collected in Year Four, then 20 percent of the gain becomes taxable in that year.

In this illustration, no cash is received in Year One so no taxable income is reported.

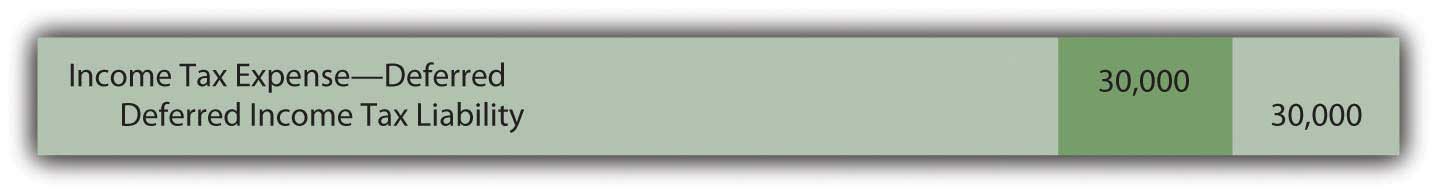

The eventual tax to be paid on the gain will be $30,000 ($100,000 × 30 percent). How is this $30,000 reported in Year One if payment is not required until Years Four and Five?

First, because of the matching principle, an expense of $30,000 is recorded in Year One. As can be seen above, the $100,000 gain is reported on the income statement in that year. Any related expense should be recognized in the same period. That is the basic premise of the matching principle.

Second, the $100,000 gain creates a temporary difference. The amount will become taxable when the cash is collected. At that time, a tax payment of $30,000 is required. Accountants have long debated whether this liability is created when the income is earned or when the payment is to be made. In legal terms, the company does not owe any money to the government until the Year Four and Year Five tax returns are filed. However, U.S. GAAP states that recognition of the gain in Year One creates the need to report the liability. Thus, a deferred income tax liability is also recorded at that time.

Consequently, the following adjusting entry is included at the end of Year One so that both the expense and the liability are properly reported.

In Year Four, the customer is expected to pay the first 20 percent of the $250,000 sales price ($50,000). If that payment is made at that time, 20 percent of the gain becomes taxable and the related liability comes due. Because $20,000 of the gain (20 percent of the total) is now reported within taxable income, a $6,000 payment ($20,000 gain × 30 percent tax rate) is made to the government, which reduces the deferred income tax liability.

Exercise

Link to multiple-choice question for practice purposes: http://www.quia.com/quiz/2092988.html

Key Takeaway

U.S. GAAP and the Internal Revenue Code are created by separate groups with different goals in mind. Consequently, many differences exist as to amounts and timing of income recognition. Business officials like to use these differences to postpone the payment of income taxes so that the money can remain in use and generate additional profits. Although payment is not made immediately, the matching principle requires the expense to be reported in the same time period as the related revenue. In recognizing this expense, a deferred income tax liability is also created that remains in the financial records until payment is made. One of the most common methods for deferring income tax payments is application of the installment sales method. According to that method, recognition of the profit on a sale is delayed until cash is collected. In the interim, a deferred tax liability is reported to alert decision makers to the eventual payment that will be required.

1Many companies also report deferred income tax assets that arise because of other differences in U.S. GAAP and the Internal Revenue Code. For example, Southwest Airlines included a deferred income tax asset of $365 million on its December 31, 2008, balance sheet. Accounting for such assets is especially complex and will not be covered in this textbook. Some portion of this asset balance, although certainly not all, is likely to be the equivalent of a prepaid income tax where the company was required to make payments by the tax laws in advance of recognition according to U.S. GAAP.

2The installment sales method can also be used for financial reporting purposes but only under very limited circumstances.

References

Iofe, Y., senior editor, and Matthew C. Calderisi, CPA, managing editor, Accounting Trends & Techniques, 62nd edition (New York: American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, 2008), 266.