14.6 Bonds with Other Than Annual Interest Payments

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Realize that interest payments are frequently made more often than annually such as quarterly or semiannually.

- Determine the stated interest rate, the effective interest rate, and the number of time periods to be used in a present value computation when interest payments cover a period of time other than a year.

- Compute the stated cash interest and the effective interest when interest payments are made more frequently than once each year.

- Prepare journal entries for a bond with interest payments made quarterly or semiannually or at some other period shorter than once each year.

Question: In the previous examples, both the interest rates and payments covered a full year. How is this process affected if interest payments are made at other time intervals such as each quarter or semiannually?

As an illustration, assume that on January 1, Year One, an entity issues bonds with a face value of $500,000 that will come due in six years. Cash interest payments at a 6 percent annual rate are required by the contract but the actual disbursements are made every six months on June 30 and December 31. The debtor and the creditor negotiate an effective interest rate of 8 percent per year. How is the price of a bond determined and the debt reported if interest payments occur more often than once each year?

Answer: None of the five basic steps for issuing and reporting a bond is changed by the frequency of the interest payments. However, both the stated cash rate and the effective rate must be set to agree with the time interval between the payment dates. The number of periods used in the present value computation is also based on the length of this interval.

In this example, interest is paid semiannually so each time period is only six months in length. The stated cash rate to be used for that period is 3 percent or 6/12 of 6 percent. Similarly, the effective interest rate is 4 percent or 6/12 of 8 percent. Both of these interest rates must align with the specific amount of time between payments. Over the six years until maturity, there are twelve of these six-month periods of time.

Thus, the cash flows will be the following:

- Interest: $500,000 face value times 3 percent stated rate or $15,000 every six months for twelve periods. Equal payments are made at equal time intervals making this an annuity. Payments are made at the end of each period so it is an ordinary annuity.

Plus

- Face value: $500,000 at the end of these same twelve periods. This payment is a single amount.

As indicated, the effective rate to be used in determining the present value of these cash payments is 4 percent per period or 6/12 times 8 percent.

Present Value of $1

http://www.principlesofaccounting.com/ART/fv.pv.tables/pvof1.htm

Present Value of an Ordinary Annuity of $1

http://www.principlesofaccounting.com/ART/fv.pv.tables/pvofordinaryannuity.htm

- The present value of $1 in twelve periods at an effective rate of 4 percent per period is $0.62460.

- The present value of an ordinary annuity of $1 for twelve periods at an effective rate of 4 percent per period is $9.38507.

- The present value of the face value cash payment is $500,000 times $0.62460 or $312,300.

- The present value of the cash interest payments every six months is $15,000 times $9.38507 or $140,776 (rounded).

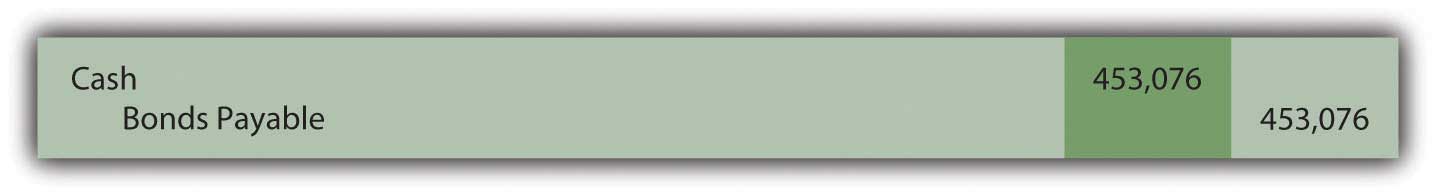

- Total present value of the cash flows set by this contract is $312,300 plus $140,776 or $453,076. The bond is issued for the present value of $453,076 so that the agreed-upon effective rate of interest (8 percent for a year or 4 percent for each six-month period) is being earned over the entire life of the bond.

Figure 14.24 January 1, Year One—Issuance of $500,000 Bond to Yield Effective Rate of 4 Percent Semiannually

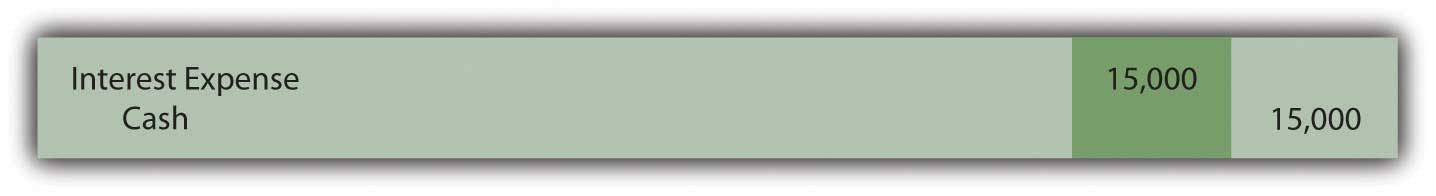

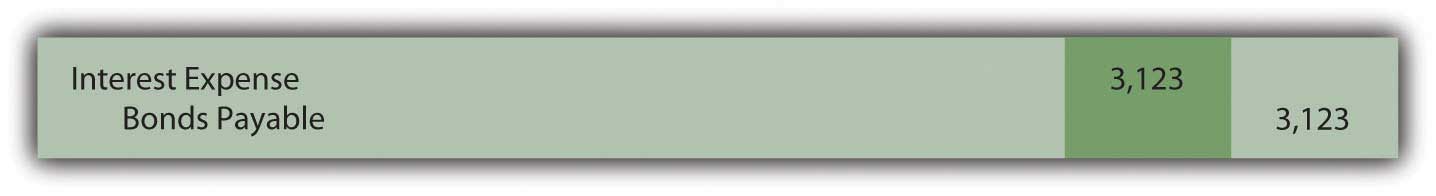

On June 30, Year One, the first $15,000 interest payment is made. However, the effective rate of interest for that period is the principal of $453,076 times the six-month negotiated rate of 4 percent or $18,123 (rounded). Therefore, the interest to be compounded for this period is $3,123 ($18,123 interest less $15,000 payment). That is the amount of interest recognized but not paid on this day.

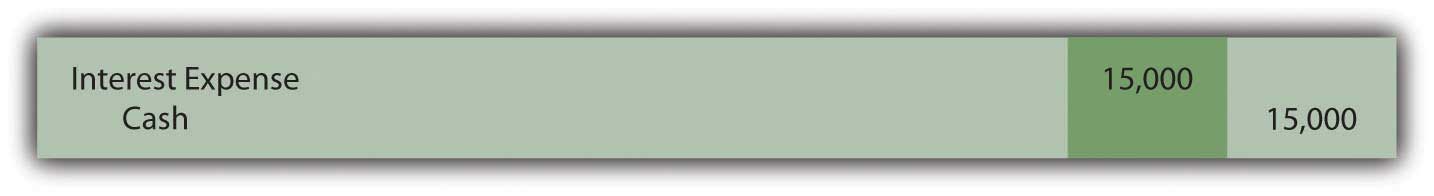

For the second six-months in Year One, the compound interest recorded above raises the bond’s principal to $456,199 ($453,076 principal for first six months plus $3,123 in compound interest). Although another $15,000 in cash interest is paid on December 31, Year One, the effective interest for this six-month period is $18,248 (rounded) or $456,199 times 4 percent interest. Compound interest recognized for this second period of time is $3,248 ($18,248 less $15,000).

The Year One income statement will report interest expense of $18,123 for the first six months and $18,248 for the second, giving a total for the year of $36,371.

The December 31, Year One, balance sheet reports the bond payable as a noncurrent liability of $459,447. That is the original principal (present value) of $453,076 plus compound interest of $3,123 (first six months) and $3,248 (second six months).

Once again, interest each period has been adjusted from the cash rate stated in the contract to the effective rate negotiated by the two parties. Here, the annual rates had to be halved because payments were made semiannually. In addition, as a result of the compounding process, the principal balance is moving gradually toward the $500,000 face value that will be paid at the end of the bond term.

Exercise

Link to multiple-choice question for practice purposes: http://www.quia.com/quiz/2093024.html

Key Takeaway

Bonds often pay interest more frequently than once a year. If the stated cash rate and the effective rate differ, present value is still required to arrive at the principal amount to be paid. However, the present value computation must be adjusted to reflect the different pattern of cash flows. The length of time between payments is considered one period. The effective interest rate is then determined for that particular period of time. The number of time periods used in calculating present value is also based on this same definition of a period. The actual accounting and reporting are not affected, merely the method by which the interest rates and the number of periods are calculated.

Talking with a Real Investing Pro (Continued)

Following is a continuation of our interview with Kevin G. Burns.

Question: Assume that you are investigating two similar companies because you are thinking about recommending one of them to your clients as an investment possibility. The financial statements look much the same except that one of these companies has an especially low amount of noncurrent liabilities while the other has a noncurrent liability total that seems quite high. Which company are you most likely to recommend?

Kevin Burns: I have done well now for many years by being a conservative investor. My preference is always the company that is debt free or as close to debt free as possible. I do not like leverage, never have. I even paid off my own home mortgage more than ten years ago.

On the other hand, long-term liabilities have to be analyzed as they are so very common. Is any of the debt convertible so that it could potentially dilute everyone’s ownership in the company? Is the company paying a high stated rate of interest? Why was the debt issued? In other words, how did the company use the money it received? As with virtually every area of a set of financial statements, you have to look behind the numbers to see what is actually happening. If the debt was issued at a low interest rate in order to make a smart acquisition, I am impressed. If the debt has a high interest rate and the money was not well used, that is not attractive to me at all.

Video Clip

Unnamed Author talks about the five most important points in Chapter 14 “In a Set of Financial Statements, What Information Is Conveyed about Noncurrent Liabilities Such as Bonds?”.