10.4 Physical Delivery

Learning Objectives

- Explain the role of facial expressions and eye contact in speech delivery.

- Explain the role of posture, gestures, and movement in speech delivery.

- Explain the connection between personal appearance and credibility in speech delivery.

- Explain the connection between visual aids and speech delivery.

Many speakers are more nervous about physical delivery than vocal delivery. Putting our bodies on the line in front of an audience often makes us feel more vulnerable than putting our voice out there. Yet most audiences are not as fixated on our physical delivery as we think they are. Knowing this can help relieve some anxiety, but it doesn’t give us a free pass when it comes to physical delivery. We should still practice for physical delivery that enhances our verbal message. Physical delivery of a speech involves nonverbal communication through the face and eyes, gestures, and body movements.

Physical Delivery and the Face

We tend to look at a person’s face when we are listening to them. Again, this often makes people feel uncomfortable and contributes to their overall speaking anxiety. Many speakers don’t like the feeling of having “all eyes” on them, even though having a room full of people avoiding making eye contact with you would be much more awkward. Remember, it’s a good thing for audience members to look at you, because it means they’re paying attention and interested. Audiences look toward the face of the speaker for cues about the tone and content of the speech.

Facial Expressions

Facial expressions can help bring a speech to life when used by a speaker to communicate emotions and demonstrate enthusiasm for the speech. As with vocal variety, we tend to use facial expressions naturally and without conscious effort when engaging in day-to-day conversations. Yet I see many speakers’ expressive faces turn “deadpan” when they stand in front of an audience. Some people naturally have more expressive faces than others—think about the actor Jim Carey’s ability to contort his face as an example. But we can also consciously control and improve on our facial expressions to be more effective speakers. As with other components of speech delivery, becoming a higher self-monitor and increasing your awareness of your typical delivery habits can help you understand, control, and improve your delivery. Although you shouldn’t only practice your speech in front of a mirror, doing so can help you get an idea of how expressive or unexpressive your face is while delivering your speech. There is some more specific advice about assessing and improving your use of facial expressions in the “Getting Competent” box in this chapter.

Facial expressions are key for conveying emotions and enthusiasm in a speech.

Jeff Wasson – Immutable Law Of The Universe #2 – CC BY 2.0.

Facial expressions help set the emotional tone for a speech, and it is important that your facial expressions stay consistent with your message. In order to set a positive tone before you start speaking, briefly look at the audience and smile. A smile is a simple but powerful facial expression that can communicate friendliness, openness, and confidence. Facial expressions communicate a range of emotions and are also associated with various moods or personality traits. For example, combinations of facial expressions can communicate that a speaker is tired, excited, angry, confused, frustrated, sad, confident, smug, shy, or bored, among other things. Even if you aren’t bored, for example, a slack face with little animation may lead an audience to think that you are bored with your own speech, which isn’t likely to motivate them to be interested. So make sure your facial expressions are communicating an emotion, mood, or personality trait that you think your audience will view favorably. Also make sure your facial expressions match with the content of your speech. When delivering something lighthearted or humorous, a smile, bright eyes, and slightly raised eyebrows will nonverbally enhance your verbal message. When delivering something serious or somber, a furrowed brow, a tighter mouth, and even a slight head nod can enhance that message. If your facial expressions and speech content are not consistent, your audience could become confused by the conflicting messages, which could lead them to question your honesty and credibility.

“Getting Competent”

Improving Facial Expressions

My very first semester teaching, I was required by my supervisor to record myself teaching and evaluate what I saw. I was surprised by how serious I looked while teaching. My stern and expressionless face was due to my anxiety about being a beginning teacher and my determination to make sure I covered the content for the day. I didn’t realize that it was also making me miss opportunities to communicate how happy I was to be teaching and how passionate I was about the content. I just assumed those things would come through in my delivery. I was wrong. The best way to get an idea of the facial expressions you use while speaking is to record your speech using a computer’s webcam, much like you would look at and talk to the computer when using Skype or another video-chat program. The first time you try this, minimize the video window once you’ve started recording so you don’t get distracted by watching yourself. Once you’ve recorded the video, watch the playback and take notes on your facial expressions. Answer the following questions:

- Did anything surprise you? Were you as expressive as you thought you were?

- What facial expressions did you use throughout the speech?

- Where did your facial expressions match with the content of your speech? Where did your facial expressions not match with the content of your speech?

- Where could you include more facial expressions to enhance your content and/or delivery?

You can also have a friend watch the video and give you feedback on your facial expressions to see if your assessment matches with theirs. Once you’ve assessed your video, re-record your speech and try to improve your facial expressions and delivery. Revisit the previous questions to see if you improved.

Eye Contact

Eye contact is an important element of nonverbal communication in all communication settings. Chapter 4 “Nonverbal Communication” explains the power of eye contact to make people feel welcome/unwelcome, comfortable/uncomfortable, listened to / ignored, and so on. As a speaker, eye contact can also be used to establish credibility and hold your audience’s attention. We often interpret a lack of eye contact to mean that someone is not credible or not competent, and as a public speaker, you don’t want your audience thinking either of those things. Eye contact holds attention because an audience member who knows the speaker is making regular eye contact will want to reciprocate that eye contact to show that they are paying attention. This will also help your audience remember the content of your speech better, because acting like we’re paying attention actually leads us to pay attention and better retain information.

Eye contact is an aspect of delivery that beginning speakers can attend to and make noticeable progress on early in their speech training. By the final speech in my classes, I suggest that my students make eye contact with their audience for at least 75 percent of their speech. Most speakers cannot do this when they first begin practicing with extemporaneous delivery, but continued practice and effort make this an achievable goal for most.

As was mentioned in Chapter 4 “Nonverbal Communication”, norms for eye contact vary among cultures. Therefore it may be difficult for speakers from countries that have higher power distances or are more collectivistic to get used to the idea of making direct and sustained eye contact during a speech. In these cases, it is important for the speaker to challenge himself or herself to integrate some of the host culture’s expectations and for the audience to be accommodating and understanding of the cultural differences.

Tips for Having Effective Eye Contact

- Once in front of the audience, establish eye contact before you speak.

- Make slow and deliberate eye contact, sweeping through the whole audience from left to right.

- Despite what high school speech teachers or others might have told you, do not look over the audience’s heads, at the back wall, or the clock. Unless you are in a huge auditorium, it will just look to the audience like you are looking over their heads.

- Do not just make eye contact with one or a few people that you know or that look friendly. Also, do not just make eye contact with your instructor or boss. Even if it’s comforting for you as the speaker, it is usually awkward for the audience member.

- Try to memorize your opening and closing lines so you can make full eye contact with the audience. This will strengthen the opening and closing of your speech and help you make a connection with the audience.

Physical Delivery and the Body

Have you ever gotten dizzy as an audience member because the speaker paced back and forth? I know I have. Anxiety can lead us to do some strange things with our bodies, like pacing, that we don’t normally do, so it’s important to consider the important role that your body plays during your speech. Extra movements caused by anxiety are called nonverbal adaptors, and most of them manifest as distracting movements or gestures. These nonverbal adaptors, like tapping a foot, wringing hands, playing with a paper clip, twirling hair, jingling change in a pocket, scratching, and many more, can definitely detract from a speaker’s message and credibility. Conversely, a confident posture and purposeful gestures and movement can enhance both.

Posture

Posture is the position we assume with our bodies, either intentionally or out of habit. Although people, especially young women, used to be trained in posture, often by having them walk around with books stacked on their heads, you should use a posture that is appropriate for the occasion while still positioning yourself in a way that feels natural. In a formal speaking situation, it’s important to have an erect posture that communicates professionalism and credibility. However, a military posture of standing at attention may feel and look unnatural in a typical school or business speech. In informal settings, it may be appropriate to lean on a table or lectern, or even sit among your audience members. Head position is also part of posture. In most speaking situations, it is best to keep your head up, facing your audience. A droopy head doesn’t communicate confidence. Consider the occasion important, as an inappropriate posture can hurt your credibility.

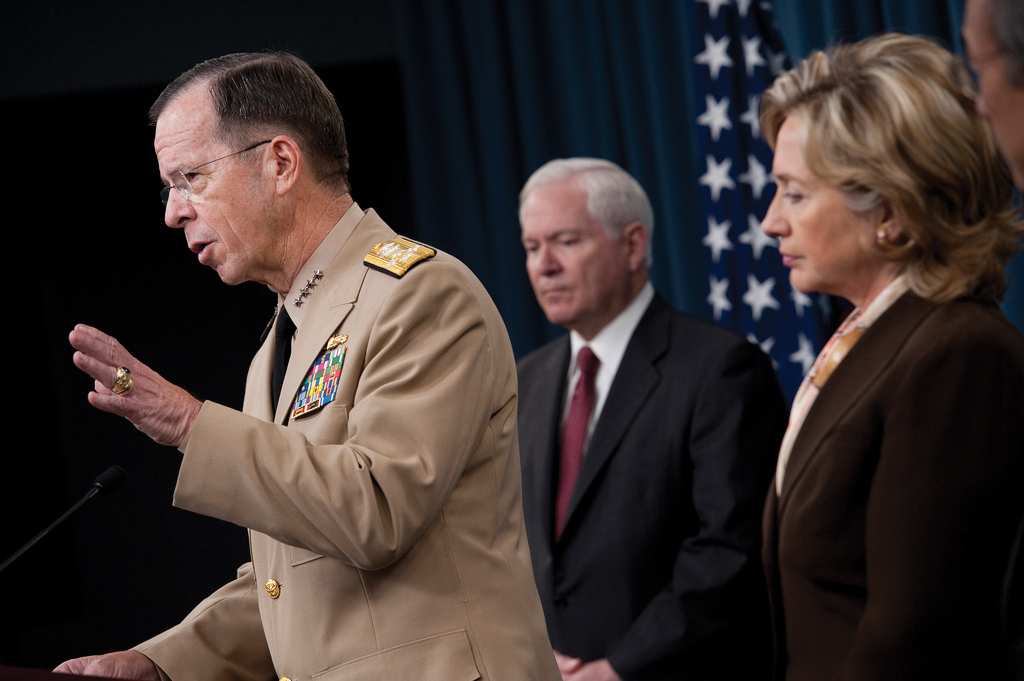

Government and military leaders use an erect posture to communicate confidence and professionalism during public appearances.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Gestures

Gestures include arm and hand movements. We all go through a process of internalizing our native culture from childhood. An obvious part of this process is becoming fluent in a language. Perhaps less obvious is the fact that we also become fluent in nonverbal communication, gestures in particular. We all use hand gestures while we speak, but we didn’t ever take a class in matching verbal communication with the appropriate gestures; we just internalized these norms over time based on observation and put them into practice. By this point in your life, you have a whole vocabulary of hand movements and gestures that spontaneously come out while you’re speaking. Some of these gestures are emphatic and some are descriptive (Koch, 2007).

Emphatic gestures are the most common hand gestures we use, and they function to emphasize our verbal communication and often relate to the emotions we verbally communicate. Pointing with one finger or all the fingers straight out is an emphatic gesture. We can even bounce that gesture up and down to provide more emphasis. Moving the hand in a circular motion in front of our chest with the fingers spread apart is a common emphatic gesture that shows excitement and often accompanies an increased rate of verbal speaking. We make this gesture more emphatic by using both hands. Descriptive gestures function to illustrate or refer to objects rather than emotions. We use descriptive gestures to indicate the number of something by counting with our fingers or the size, shape, or speed of something. Our hands and arms are often the most reliable and easy-to-use visual aids a speaker can have.

While it can be beneficial to plan a key gesture or two in advance, it is generally best to gesture spontaneously in a speech, just as you would during a regular conversation. For some reason, students are insecure about or uncomfortable with gesturing during a speech. Even after watching their speech videos, many students say they think they “gestured too much” or nit-pick over a particular gesture. Out of thousands of speeches I’ve seen, I can’t recall a student who gestured too much to the point that it was distracting. Don’t try to overdo your gestures though. You don’t want to look like one of those crazy-arm inflatable dancing men that companies set up on the side of the road to attract customers. But more important, don’t try to hold back. Even holding back a little usually ends up nearly eliminating gestures. While the best beginning strategy is to gesture naturally, you also want to remain a high self-monitor and take note of your typical patterns of gesturing. If you notice that you naturally gravitate toward one particular gesture, make an effort to vary your gestures more. You also want your gestures to be purposeful, not limp or lifeless. I caution my students against having what I call “spaghetti noodle arms,” where they raise their hand to gesture and then let it flop back down to their side.

Movement

Sometimes movement of the whole body, instead of just gesturing with hands, is appropriate in a speech. I recommend that beginning speakers hold off trying to incorporate body movement from the waist down until they’ve gotten at least one speech done. This allows you to concentrate on managing anxiety and focus on more important aspects of delivery like vocal variety, avoiding fluency hiccups and verbal fillers, and improving eye contact. When students are given the freedom to move around, it often ends up becoming floating or pacing, which are both movements that comfort a speaker by expending nervous energy but only serve to distract the audience. Floating refers to speakers who wander aimlessly around, and pacing refers to speakers who walk back and forth in the same path. To prevent floating or pacing, make sure that your movements are purposeful. Many speakers employ the triangle method of body movement where they start in the middle, take a couple steps forward and to the right, then take a couple steps to the left, then return back to the center. Obviously you don’t need to do this multiple times in a five- to ten-minute speech, as doing so, just like floating or pacing, tends to make an audience dizzy. To make your movements appear more natural, time them to coincide with a key point you want to emphasize or a transition between key points. Minimize other movements from the waist down when you are not purposefully moving for emphasis. Speakers sometimes tap or shuffle their feet, rock, or shift their weight back and forth from one leg to the other. Keeping both feet flat on the floor, and still, will help avoid these distracting movements.

Credibility and Physical Delivery

Audience members primarily take in information through visual and auditory channels. Just as the information you present verbally in your speech can add to or subtract from your credibility, nonverbal communication that accompanies your verbal messages affects your credibility.

Personal Appearance

Looking like a credible and prepared public speaker will make you feel more like one and will make your audience more likely to perceive you as such. This applies to all speaking contexts: academic, professional, and personal. Although the standards for appropriate personal appearance vary between contexts, meeting them is key. You may have experienced a time when your vocal and physical delivery suffered because you were not “dressed the part.” The first time I ever presented at a conference, I had a terrible cold and in my hazy packing forgot to bring a belt. While presenting later that day, all I could think about was how everyone was probably noticing that, despite my nice dress shirt tucked into my slacks, I didn’t have a belt on. Dressing the part makes you feel more confident, which will come through in your delivery. Ideally, you should also be comfortable in the clothes you’re wearing. If the clothes are dressy, professional, and nice but ill fitting, then the effect isn’t the same. Avoid clothes that are too tight or too loose. Looking the part is just as important as dressing the part, so make sure you are cleaned and groomed in a way that’s appropriate for the occasion. The “Getting Real” box in this chapter goes into more detail about professional dress in a variety of contexts.

“Getting Real”

Professional Dress and Appearance

No matter what professional field you go into, you will need to consider the importance of personal appearance. Although it may seem petty or shallow to put so much emphasis on dress and appearance, impressions matter, and people make judgments about our personality, competence, and credibility based on how we look. In some cases, you may work somewhere with a clearly laid out policy for personal dress and appearance. In many cases, the suggestion is to follow guidelines for “business casual.” Despite the increasing popularity of this notion over the past twenty years, people’s understanding of what business casual means is not consistent (Cullen, 2008). The formal dress codes of the mid-1900s, which required employees to wear suits and dresses, gave way to the trend of business casual dress, which seeks to allow employees to work comfortably while still appearing professional (Heathfield, S. M., 2012). While most people still dress more formally for job interviews or high-stakes presentations, the day-to-day dress of working professionals varies. Here are some tips for maintaining “business casual” dress and appearance:

- Things to generally avoid. Jeans, hats, flip-flops, exposed underwear, exposed stomachs, athletic wear, heavy cologne/perfume, and chewing gum.

- General dress guidelines for men. Dress pants or khaki pants, button-up shirt or collared polo/golf shirt tucked in with belt, and dress shoes; jacket and/or tie are optional.

- General dress guidelines for women. Dress pants or skirt, blouse or dress shirt, dress, and closed-toe dress shoes; jacket is optional.

- Finishing touches. Make sure shoes are neat and polished, not scuffed or dirty; clothes should be pressed, not wrinkled; make sure fingernails are clean and trimmed/groomed; and remove any lint, dog hair, and so on from clothing.

Obviously, these are general guidelines and there may be exceptions. It’s always a good idea to see if your place of business has a dress code, or at least guidelines. If you are uncertain whether or not something is appropriate, most people recommend to air on the side of caution and choose something else. While consultants and professionals usually recommend sticking to dark colors such as black, navy, and charcoal and/or light colors such as white, khaki, and tan, it is OK to add something that expresses your identity and makes you stand out, like a splash of color or a nice accessory like a watch, eyeglasses, or a briefcase. In fact, in the current competitive job market, employers want to see that you are serious about the position, can fit in with the culture of the organization, and are confident in who you are (Verner, 2008).

- What do you think is the best practice to follow when dressing for a job interview?

- In what professional presentations would you want to dress formally? Business casual? Casual?

- Aside from the examples listed previously, what are some other things to generally avoid, in terms of dress and appearance, when trying to present yourself as a credible and competent communicator/speaker?

- In what ways do you think you can conform to business-casual expectations while still preserving your individuality?

Visual Aids and Delivery

Visual aids play an important role in conveying supporting material to your audience. They also tie to delivery, since using visual aids during a speech usually requires some physical movements. It is important not to let your use of visual aids detract from your credibility. I’ve seen many good speeches derailed by posters that fall over, videos with no sound, and uncooperative PowerPoint presentations.

The following tips can help you ensure that your visual aids enhance, rather than detract, from your message and credibility:

- Only have your visual aid displayed when it is relevant to what you are saying: insert black slides in PowerPoint, hide a model or object in a box, flip a poster board around, and so on.

- Make sure to practice with your visual aids so there aren’t any surprises on speech day.

- Don’t read from your visual aids. Put key information from your PowerPoint or Prezi on your speaking outline and only briefly glance at the screen to make sure you are on the right slide. You can also write information on the back of a poster or picture that you’re going to display so you can reference it while holding the visual aid up, since it’s difficult to hold a poster or picture and note cards at the same time.

- Triple check your technology to make sure it’s working: electricity, Internet connection, wireless clicker, sound, and so on.

- Proofread all your visual aids to find spelling/grammar errors and typos.

- Bring all the materials you may need to make your visual aid work: tape/tacks for posters and pictures, computer cables/adaptors, and so on. Don’t assume these materials will be provided.

- Have a backup plan in case your visual aid doesn’t work properly.

Key Takeaways

- Facial expressions help communicate emotions and enthusiasm while speaking. Make sure that facial expressions are consistent with the content being presented. Record yourself practicing your speech in order to evaluate your use of facial expressions.

- Eye contact helps establish credibility and keep your audience’s attention while you’re speaking.

- Posture should be comfortable and appropriate for the speaking occasion.

- Emphatic and descriptive gestures enhance the verbal content of our speech. Gestures should appear spontaneous but be purposeful.

- Movements from the waist down should be purposefully used to emphasize a point or as a transition during a speech.

- Audience members will make assumptions about your competence and credibility based on dress and personal appearance. Make sure your outer presentation of self is appropriate for the occasion and for the impression you are trying to project.

- Visual aids can add to your speech but can also interfere with your delivery and negatively affect your credibility if not used effectively.

Exercises

- Identify three goals related to delivery that you would like to accomplish in this course. What strategies/tips can you use to help achieve these goals?

- What nonverbal adaptors have you noticed that others use while speaking? Are you aware of any nonverbal adaptors that you have used? If so, what are they?

- Getting integrated: Identify some steps that speakers can take to ensure that their dress and physical appearance enhance their credibility. How might expectations for dress and physical appearance vary from context to context (academic, professional, personal, and civic)?

References

Cullen, L. T., “What (Not) to Wear to Work,” Time, June 9, 2008, 49.

Heathfield, S. M., “Dress for Success: A Business Casual Dress Code,” About.com, accessed February 7, 2012, http://humanresources.about.com/od/workrelationships/a/dress_code.htm.

Koch, A., Speaking with a Purpose, 7th ed. (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2007), 105.

Verner, A., “Interview? Ditch the Navy Suit,” The Globe and Mail, December 15, 2008, L1.