6 Teacher Response to Children’s Texts

When my younger daughter made disparaging remarks about Billy Budd I rushed to Melville’s defense with a speech on the conflict between the rule of law applied generically and the merits of individual cases. Billy Budd struck a superior officer, I reminded her; according to the letter of the law, he must hang. And yet, and yet, we cannot quite swallow it. I ended in a glow of ambivalence. “It wasn’t that he struck him,” she murmured. “He killed him.”

Lynne Sharon Schwartz

True Confessions of a Reader

The last three chapters have been true confessions of a reader. I read the nonverbal, oral, and written texts of third graders in my writing workshop, and told stories about student intention, the risks, for children, of writing, the lure of fiction. I warmed myself a little (and you, I hope) in the glow of ambivalence, that pleasure we get from playing with complexity and contradiction when we do not have to decide what is to be done with Billy Budd, or James, or Jessie. Lynne Sharon Schwartz’s younger daughter murmurs in this chapter. Here are the confessions of a teacher struggling with complexity and contradiction, warmed by nervousness, frustration, and the heat of confrontation between actual people, not just the clash of meanings and interpretations.

Maya’s text, The Zit Fit: The Lovers in the School, provoked oral responses to Maya on two successive days, and five pages of written notes on the night in between–five pages written after I seemed to be wrapping up my notewriting with this comment: “I’m running out of gas very quickly (it’s after midnight). Some brief comments on Maya’s text” (Fieldnotes, 3-8-90). The comments were not brief. As I read Maya’s story and wrote and thought about the problems and issues I had to confront, I worried more and more about what a responsible sort of response would look like in this situation.

In what follows, I offer a story and an interpretation of my oral and written responses to Maya and her text. Interpretation, as Scholes (1985) reminds us, “depends upon the failures of reading. It is the feeling of incompleteness on the reader’s part that activates the interpretive process” (p. 22). In this case, it is the two conceptions of teacher response to children’s texts that I brought to this work (discussed in chapter 1) that lead to “failures of reading.” Both following the child and response as socioanalysis, as conceptions of teacher response to children’s texts, proved inadequate for reading (making sense of) what happened and what was at stake. As I tell the story of my response to Maya’s text, I also begin a critique of these conceptions of response that I continue in the final chapter.

My story begins at least a month before I saw Maya’s The Zit Fit, with a flurry of oral and written texts involving and surrounding Jessie. Some of these texts taught me about the word “zits” (slang for pimples) and the local uses it was put to by these third graders. Other texts suggested a possible friendship, or at least some connection, between Jessie and Jil that I had not picked up on in the classroom, and that would become important for my later response to Maya’s story.

On a Wednesday morning in early February, I got to school before the children were allowed into the school building. Groups of children often met me as I walked from the parking lot to say hello, tease me–“Hello Mr. Lens-crafter” (the eyeglass specialists) was an enduring favorite–or, on cold mornings, to complain about having to wait outside. On this day, I saw Suzanne and Robert, among others, yelling at Jessie, calling her “zit face.” I told them to stop it, and made a point to walk up to Jessie, touch her on the shoulder, and say good morning. Jessie paused long enough to say hello before continuing her own verbal defense and attack.

These verbal fights continued over the next few days. I wrote in my notes that “Jessie has been doing battle with Mary, Suzanne, Carol, and even sometimes, it seems, her friends Karen and Janis. But primarily with Suzanne and Mary” (Fieldnotes, 2-9-90). Friday, during writing time, I talked with Jessie about a book she had recently published. She refused to share it with any of her classmates.

I went out into the hall with Jessie, we sat on the floor, and she read her My Friends story. She had on outrageous tights (white with big black polka dots) and a polka dot dress, pink. The day before, she came to school with two piggy tails that stood straight up in the air. She complained about them to me, and dared me to say she didn’t look awful. When I said I thought her pigtails looked interesting, she walked away. (Fieldnotes, 2-9-90)

Jessie’s book had two chapters. The first chapter was entitled “The Fight,” and read:

I found another text connecting Jessie and Jil a little later that same day, in the wastebasket (see Figure 6.1). I noticed it when the children left for lunch. In the story, Jil, Jessie, and Paul sing a “dumb” song together before Lisa shoots Jessie in the back. I do not know who the author was, or why he or she threw it away. (It may have been a remnant from Lisa’s soap opera, discussed briefly in the last chapter, that I had not seen.)

Actually, I have a guess as to at least one reason it was thrown away. The attack on Jessie was not the only one accomplished with the piece of paper I found in the wastebasket. Below the story reproduced in Figure 6.1 was a message, written in cursive. The message read: “Mary you’r stupid!” It was written twice, once in pen and once in pencil. On the back of the paper was: “To: Mary.” Maybe the author of “The Killers” ran out of paper, and used the empty space beneath the story for a message, which Mary received and then threw away. Or perhaps the story itself was the first message, and was given to Jessie, Jil, Paul, or maybe even Lisa, by Mary, who then received a critical response to her work–you’r stupid–which she threw away. In any event, the story again associated Jessie with Jil; and Jessie was being attacked in real life and as a fictional character.

When I was writing my notes that night, I remembered that I had run into “zit face” in a writing conference even before I had heard it used orally against Jessie. Suzanne had been writing a rather impressive text inspired by a novel–Margaret Sidney’s Five Little Peppers and How They Grew–her grandmother had given to her. Suzanne’s book was entitled, The Missing Piece, and told stories about a family of sisters and brothers and their father–the mother had died. The book had five chapters, and one of them was entitled “Zit Face.” This particular chapter involved Kim, her father, her brother Ken, and her older sister Elaine.

Kim was getting so much zits she did not want to go to school. Nobody liked Kim. Her new name was Zit Face. Her friends said, “Run, run, as fast as you can, you can’t catch me you’re the Zit man.” They called her Zit man because all the boys in 5th grade had Zits. Ken would sing the song on the bus and on the playground and at home. Dad would ground him if he was around when he would sing it by Dad. Dad was very strict. “Run, run, run, as fast as you can, you can’t catch me you’re the Zit man, Zit, Zit, Zit, man, man, man.”

“Stop it!” outbursted Elaine.

Suzanne seems to have appropriated and transformed (a la Bakhtin) a children’s song about a gingerbread man for her own purposes. The song usually goes, “Run, run, as fast as you can, you can’t catch me I’m the gingerbread man.” The residual influence of the traditional song might account for the shift from “Zit Face” in the title of the chapter and the beginning of the story (“Her new name was Zit Face”), to “Zit man“in Ken’s song–also, “Zit man” completes the rhyme with “can”; “face” would not.

But the song also shows traces of the sort of chasing games and teasing Thorne (1986) described in relation to “female pariahs” in elementary schools. These girls were often called “cootie queens,” and cooties, a sort of imaginary social virus, could be spread with physical contact. Chasing games, where the person caught and touched got cooties, and elaborate rules for avoiding and passing on cooties, revolved around these unfortunate girls labeled as “cootie queens.” Such games functioned to isolate these girls from other children.

Suzanne’s story suggests that “zits” might have served similar functions to “cooties.” Ken’s song in the story sets up a chase, and expresses the perspective of the one being chased. The song is directed at the Zit man (Kim in Suzanne’s story), perhaps called over the shoulder during the chase, and tells her that she can run as fast as she wants, but she will never catch him. The song instructs the one with zits on the futility of trying to make contact with others–they will continue to actively avoid her, try as she might.

Suzanne’s use of “zit face” and “zit man” in her written text paralleled oral uses of such words, by her and others, to tease and isolate Jessie before school. Suzanne may have had Jessie in mind when she made up the character of Kim. I found it interesting that, given what I saw of Suzanne’s treatment of Jessie in real life, her story included a condemnation of just this sort of teasing by two important characters in her book: the father and Elaine. I had written in my fieldnotes at the time that “while the character [Kim] is cruelly treated in the story, the father does not condone it” (Fieldnotes, 2-9-90).

The father’s actions in Suzanne’s story were not so surprising–we might expect a young writer to portray a parent as censuring such teasing, even if the child herself did not see any problem with teasing other children. But having Elaine “outburst” “Stop it!” was different. In the other chapters, Elaine is presented by Suzanne as an intelligent, caring older sister. That Suzanne had Elaine object to Ken’s teasing suggests an evaluative position, on the author’s part, that at least recognized the questionable nature of such teasing and its possible consequences for the person teased. Later, I will argue that Maya took no such evaluative position in The Zit Fit, and that this was one of the things that concerned me in my response to it.

I had collected some records of what individual children were working on at different times during the year. In early February, at the same time that Suzanne and Jessie were producing the oral and written texts discussed above, Maya was working on The Zit Fit: The Lovers in the School. “Zit face” and “zit man” and “zit fit” were in the air and on the page.

Maya had been asking to share the last couple days. She got put off on Wednesday because, with the shortened period, we didn’t have any sharing. Today, I intended for her to share, but several obstacles arose. I wanted to conference with her about what she was going to share. The sharing sessions haven’t been going well–because of long, boring texts, ineffective reading, the arrangement (kids too far away to see illustrations), maybe kids are alienated from the particular author, busy writing/reading themselves, etc. And Maya has some confusing texts which are hard to follow. Maya couldn’t find her text at first–I conferenced with other people, and finally got to Maya a little before sharing time. (Fieldnotes. 3-8-90)

I called Maya over to the round table toward the side of the room. As she sat down, we started talking:

LENSMIRE: Okay, what do you want to share?

MAYA: It’s only chapter 1.

LENSMIRE: Okay, what is this zit fit thing, what is this about?

MAYA: Her name is Jil and she loves Jake, okay? You want me to read it to you?

LENSMIRE: Let me read parts and you can explain it to me. (I start reading) “Once there was a girl named Jil. One day she wanted zits to get a boyfriend.” What does that mean?

MAYA: She wanted zits.

LENSMIRE: And then she could get a boyfriend?

MAYA: Yes. (Long pause, about 8 seconds. I read a few more lines silently)

LENSMIRE: How do you think Jil’s going to feel about her name being in it? We should talk to Jil.

MAYA: Oh we told her, we already told her.

LENSMIRE: Let’s, let’s ask … Jil? (Jil walks over to the table) You’re in this, or your name is in this zit fit thing. Is that all right with you? If it’s not then we’ll have to, we’ll ask Maya to change the name. Tell you what, Maya–

MAYA: It’s not true.

LENSMIRE: Let’s do this Maya–

MAYA: I’m not changing–

LENSMIRE: Maya, Maya, this is what we need to do. Uh, let’s let Jil read it, okay? Jil doesn’t agree to it, you’ll have to go back and change the name of it, okay? I’m a little worried because I don’t want people’s feelings to be hurt by this.

MAYA: Hey, I’ve already changed James’ name.

LENSMIRE: Uh, huh. But we just have to, we just have to be careful, okay? So this is what we’re going to do. I’m going to ask Lisa to read her story today and I’m going to write “Friday” here, for Maya. (I write “Friday” in the left margin of Maya’s text. In the background, Grace is bringing the writing time segment of the workshop period to a close, and asking the class to get ready for sharing time.) Then, what we’re going to do is let Jil read it and then I’m going to read it, and hopefully you’ll be able to read it tomorrow in class. Do you have another piece you’d like to read in case this one doesn’t come through? (Maya nods) Okay, all right, can you give this to Jil then?

MAYA: Yes. (Audiotape, 3-8-90)

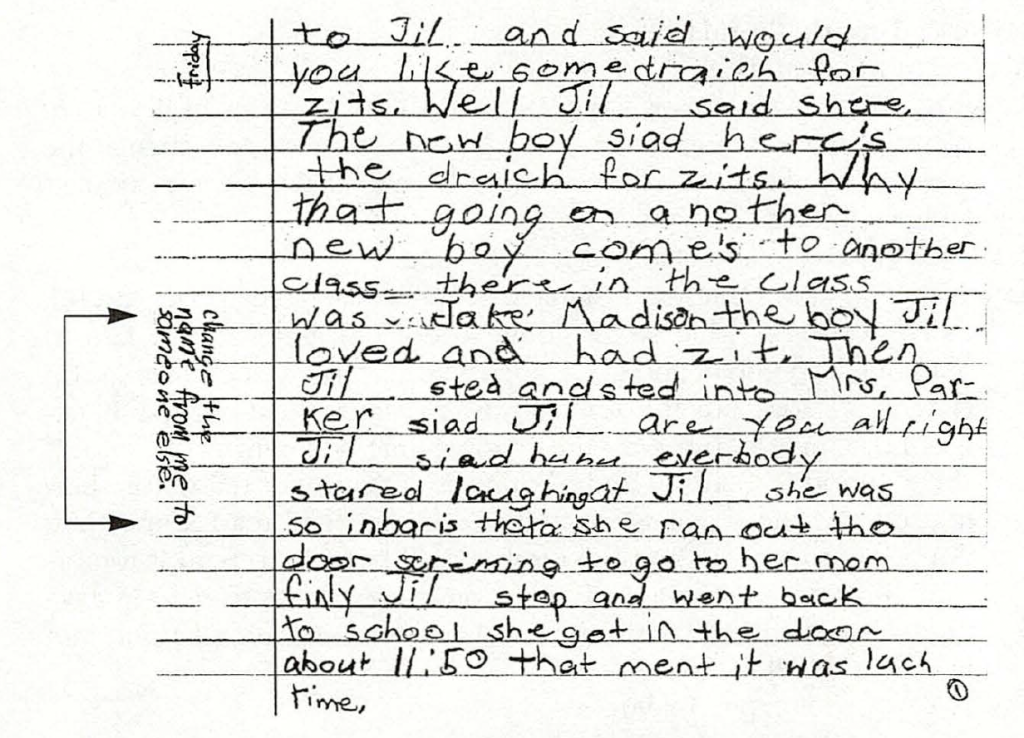

I had not read the entire text. Maya gave it to Jil, who took it back to her seat to read. After sharing time, Jil gave me Maya’s story. Jil had written, in the left margin in pencil, “change the name from me to someone else” (see Figure 6.2).

That night I read Maya’s story through (I have done some editing in the version below):

The Zit Fit: The Lovers in the School

Once there was a girl named Jil. One day she wanted zits to get a boyfriend. When Jil went to school there was a new boy. He went to Jil and said, “Would you like some drugs for zits?” Well Jil said, “Sure.” The new boy said, “Here’s the drugs for zits.”

With that going on, another new boy comes to another class. There in the class was Jake Madison, the boy Jil loved and (who) had zits. Then Jil stared and stared until Mrs. Parker said, “Jil, are you all right’?”

Jil said, “Hu hu.” Everybody started laughing at Jil. She was so embarrassed that she ran out the door screaming to go to her mom. Finally Jil stopped and went back to school. She got in the door about 11:50. That meant it was lunch time. After lunch it was recess. Jake wanted Jil to play with him. Jil knew she could not let Jake down, so Jil went to Jake and Jil said, “Would you like to play with me’?”

Jake said, “Sure, if you want.”

Jil said, “I didn’t have anyone to play with so you were my last hope.”

Jake said, “OK, let’s go play with the fat boys.” Jil said, “They always beat me up.”

Jake said, “I’ll make sure they won’t.” Jil could tell Jake loved her. When they went to the fat boys they did beat Jil up. Jake scared them away. After that Jake turned around and kissed Jil.

In the conference, I began reading Maya’s text as a fictional narrative. There were common markers for the beginning of a story–“Once” and “One day”–and a main character and the problem she faced were established (Jil wanted a boyfriend). I was puzzled, and a little repulsed, by the idea that the character of Jil would want zits, and I asked Maya, “What does this mean?” I was trying to make sense of the fictional world Maya was creating. After she answered with, “She wanted zits,” I made a sort of prediction to see if I understood how things worked in this strange place: “And then she could get a boyfriend?”

After Maya answered, there was a pause, and when I began talking with Maya again, my reading of what sort of text this was had shifted from a fictional narrative to a written version of the verbal attacks children subjected each other to on the playground and in the classroom. I now read the text as an utterance that participated directly in the immediate social relations of real children in the room. I was worried about people being hurt by this text: “How do you think Jil’s going to feel about her name being in it?” Ethical and political issues were at stake: how we would treat each other here; what rights people had to control an important part of their identities–their names; what part texts such as this one played in establishing, maintaining, and changing social relations among children.

Why did my reading of Maya’s text shift in the conference? And was the shift justified? I am guessing that during the long pause, I read at least to the line where “Jake Madison” was introduced. Maya had erased, incompletely, the name “James” and written “Jake” over it, leaving “Jake Madison.” This did not conceal who she was referring to very effectively, since James Madison was a child in the class, our author of The Fake Line Leader from Alabama. This, plus the unusual spelling of “Jil,” with Jil in the class spelling her name that way, probably moved me to my second reading. As to whether or not the shift was justified, that was one of the things I tried to figure out in my fieldnotes that night.

Maya never gave any indication that “Jil” did not refer to Jil (Jil is usually spelled with two l’s, connecting “Jil” to Jil–of course, a third grader might not have experience with another spelling). In her response, Jil says “change the name from me.” Does this mean Jil did read it as a reference to herself, or is it that writing something like “change the character’s name of Jil to another name” is more difficult? But both Maya’s revision (changing “James” to “Jake”) and Jil’s use of “me” suggest that Jil and James are in the story. (Fieldnotes. 3-8-90)

I ignored, in the above, a fairly obvious clue that located this story in this classroom–Maya uses the regular classroom teacher’s name, Mrs. Parker, in her story.

I also tried to justify my reading of Maya’s text as a verbal attack with reference to what I knew about the word “zit,” and by contrasting it to Suzanne’s chapter, “Zit Face.”

The zit thing is troubling, especially given the import of the word “zit” in the class. It was the word used to ostracize Jessie. And whereas Suzanne pulls it off, Maya doesn’t. How doesn’t she pull it off? She doesn’t recognize and note how hurtful this could be. (Fieldnotes. 3-8-90)

In these notes, I made an explicit connection between Maya’s use of the word “zit” and the teasing I had watched Jessie endure. And the texts that I had read (and discussed above), in which Jessie and Jill were connected to each other, strengthened the association I made between what was happening to Jil in Maya’s story and what had happened with Jessie.

I also invoked Suzanne’s chapter in this note, and attempted to criticize Maya’s text through contrast. “This” in the final line of my fieldnotes clearly referred to the use of the word “zits” in Maya’s story. Suzanne’s story had characters that voiced objections to verbal attacks on another character. She had “pulled off” telling a story about children teasing one another using the word “zits,” without making their behavior seem entirely acceptable. That seems to be what I was concerned with here. Maya, however, apparently does not pull this off, because she “doesn’t recognize and note how hurtful this [using ‘zits’] could be.”

But this evaluation missed the way Maya’s text worked. Suzanne could have characters tease and object to teasing–could “recognize and note how hurtful this could be”–because these things happened within the fictional world she had created. Maya’s text was different. Verbal attacks using the word “zits” do not occur within the fictional world Maya created (although other sorts of attacks did–I address this later). In fact, one of the things that bothered me right at the beginning of our conference was the seeming positive evaluation of zits by the characters of Jil and James. Maya said that Jil wanted zits so she could get a boyfriend. Consequently, it makes little sense to demand that Maya somehow object, in her story, to teasing involving “zits,” since that does not occur there.

What I interpreted as a verbal attack on Jil was not accomplished by having one character in the story call another character “zit face” or “zit man” (as had happened in Suzanne’s story). Instead, the attack depended on attributing to Jil (and James) a desire for something most people seek to avoid: zits. I may have been more repulsed by this attribution to Jil than third graders would be. That is, I might bring meanings to “zits” as an adult–adolescent memories of pimples that sprouted before important dates, or the association of acne with infection–that younger children would not bring. Still, the uses of “zits” by third graders for exclusion and hurting others made it a potent word, and one I doubted Jil or James would want to be associated with.

In the first moments of our writing conference, I shifted from reading Maya’s text as a fictional narrative to reading it as a verbal attack on children in the room. My response assumed that the text would be read by children in the class as involving actual children–Jil and James. With this assumption, my response became caught up in a fairly direct way with social relations, norms, and the sharing of texts within the writing workshop.

One of the reasons Maya’s story disturbed me was because I associated it with the verbal attacks I saw Jessie encounter. Jessie was not a passive victim, nor did she think of herself in those terms, but she often fought back alone against groups of children. Jil was also often alone in the workshop, although not as unpopular as Jessie. My sense of who the underdogs were among the children, and wanting to insert myself in these relations of power for their benefit, influenced my response. My sense of such things, of course, could have been wrong.

Carol, on several occasions and in relation to Maya’s story, told me just that–that I was wrong. It turned out that Carol was something of a secret collaborator with Maya on this text, probably the other of the “we” Maya referred to in our writing conference when she said, “Oh we told her, we already told (Jil)” about the story. When Carol found out later that I wanted Maya to change the character’s name from Jil to something else, she told me that Jil just had us teachers fooled, that she was “not such a nice person at all” (Fieldnotes, 3-13-90). I recorded my perceptions of who I thought Maya, James, and Jil were in the classroom community and how this influenced my reading of Maya’s text in my notes:

The story can be read as a double-pronged attack on Jil and James, with different intents. The story is insulting to both Jil and James. Both read it that way themselves (or at least Maya anticipated James would and changed his first name). Unless you argue that they just wouldn’t want to be in any text that Maya wrote, which is possible.

The story is insulting to them on one level because of the boy/girl thing (teasing might be a better word). It’s also insulting for Jil because she “wants zits,” she embarrasses herself in front of the teacher, she doesn’t have anyone to play with except for a boy (Jake/James), she gets beat up, and she gets kissed.

For James, besides the insult of interacting with a girl, defending her, and kissing her, there is a status thing. Jil is not in the in group (does not play or work, as far as I know, with Lisa, Mary, Carol). Therefore, to be associated with Jil might be especially insulting.

Maya’s position seems closer to James than Jil–is this a sort of high-status teasing by suggesting a cool person likes an uncool person? Perhaps Maya is scoring points with friends for teasing a popular boy and slamming an unpopular girl. (Fieldnotes. 3-8-90)

I was assigning motives here and reading for children–highly speculative activities. Maya’s text, with its references to zits and Jil and James, had forced me to consider the rhetorical effects of a child’s story. This was the first time during the year that I had tried, in any sustained way, to do such a reading. In an important sense, I began this book with the attempt. From my work with these children across 6 or so months, I was trying to determine possible meanings of the text in this particular setting. Possible meanings–I did not necessarily feel confident in my assessments of social relations and local meanings at the time.

Would my response have been different if a different group of children were involved as author and characters? I am sure it would have been. I might have attributed, for example, a defensive posture to Jessie if she had authored the piece, instead of what seems the attribution–correct or incorrect–of an offensive, aggressive posture on the part of Maya. I worried a little about this attribution in my fieldnotes, both for what it meant for my future relationship with Maya, and for what it said about me and my past relations with Maya.

So, ultimately, I’m thinking of censuring this piece because it feels ugly and hurtful. How do I say that to Maya? What effect does this have on her when I encourage her to write about things that she cares about, is interested in? And, to be truthful, I also have to ask about how my response is affected by my own relationship with Maya–I am often frustrated with her behavior in class, so am I using this text to get back at her a little, even if “justified?” (Fieldnotes. 3-8-90)

But it is unlikely that any author would have been allowed to share The Zit Fit that day in class. Why? My response to Maya’s text depended upon one of the ways I had previously inserted myself into the social relations of children in the writing workshop–a rule about names–and that rule would have been in effect whoever the author was.

Almost from the beginning of the year, children wrote themselves, their friends, and their enemies into stories. Students soon began voicing complaints, and Grace and I also became concerned as we read some children’s texts. Eventually, Grace told the children that they could not write anything mean about others. I agreed with Grace’s intent–she wanted children to respect and not hurt one another–but not with the rule. I had two concerns. One was preserving the norm of student ownership. I wanted children to be able to write what they wanted, to control their own texts as far as was possible. And, at times, this might include writing mean things about others. This was connected to my second concern. Given my experience with children, I was worried about how they would interpret the word “mean.” I wanted to leave a space open for anger and criticism in their writing–directed, perhaps, at authority figures, bullies.

The rule eventually put in place was more specific, and specific to our classroom. I invoked it with Maya immediately after the long pause in which I shifted my reading of her text. I said, “How do you think Jil is going to feel about her name being in it? We should talk toJil.” I interpret some of Maya’s responses–“Oh we told her” and “I’ve already changed James’ name”–as at least partial acknowledgement of this rule, if not agreement with its use in this case. I gave a rough statement of the rule in my notes that night:

I immediately invoked the rule that has emerged. To go public with a text, the names of characters must be approved by people in the room who have those names. (Fieldnotes. 3-8-90)

Quite a bit was at stake here. The rule attempted to balance protecting children’s feelings and establishing a supportive classroom environment against student control of text. The rule assumed a private/public distinction: Children had control over writing they kept private (they could include other children’s names in their stories). But if those stories were to go public, the use of children’s names had to be approved by the children involved. Student control, versus teacher control, was served by this rule in another way. The rule did not depend on the teacher to determine the “meaning” of a particular writer’s use of a child’s name. That determination was left to the child. As a teacher, I tried to enforce the rule, lend my institutional authority to its enactment.

Another issue was involved here. The rule gave children control over the stories that were told about them, at least in public. Writing workshop approaches are based on the idea that children’s own voices and stories should be heard in writing classrooms. But Graves, Calkins, and Murray do not seem to worry about children writing stories for others. The issue is: Who gets to tell whose story? The workshop provided a public sphere in which various individuals and groups defined themselves and others in their writing. Much like the struggles women, people of color, members of the working class, and others, have taken up to define themselves, to have their own tell their own stories (instead of white, elite males), there were struggles for definition of self within the workshop. Jil must have thought something was at stake when she wrote, “change the name from me to someone else.”

With the rule about names, I tried to intervene in these struggles in order to give individual children control over the use of their own names in the workshop. Who threatened individual children’s control of their names? Who threatened to silence certain children by making them the “objects” of someone else’s stories, rather than the subjects of their own? My discussion, in chapter 5, of who did and did not write themselves explicitly into fictional texts as characters provides an answer–other children. And in particular, children with high status and power in the room. My examples there came from texts that were made public before I understood much about children’s responses to seeing their names in other people’s stories. The most striking example of children silencing other children, of reducing other children to “objects,” was Mary and Suzanne’s casting of John, Leon, and Robert as towers in their play. I shared Mary and Suzanne’s text in the context of a discussion of public texts, so I probably misled you. That text did not go public.

And if I remained silent here, I could mislead you again, for good effect. But the rule about names did not impede their play’s progress to larger audiences. When they first showed it to me, I did not pay much attention to their list of characters. Mary and Suzanne wanted to enter their play in a contest sponsored by a local theater group, and needed my signature on an application form that certified, among other things, that the play was the original work of the authors. With pen in hand, I learned that Suzanne and Mary copied their play out of a book in the school library. Actually, they condensed the adult author’s play quite skillfully. Or, if you prefer, they appropriated her words for their own purposes. But that is another story.

But not entirely. The rule about names was supposed to give control over certain words–children’s names–to the children who claimed them as their own. It was supposed to keep authors from appropriating other children’s names for their own purposes, unless those children went along with the author’s purposes. The rule had emerged, and I had enforced it, before I understood its significance. It “assumed” what I was just beginning to articulate for myself in my response to Maya’s text–that children could turn their texts to purposes I had not anticipated, and that I could not support if I wanted all children to “come to voice” in the writing workshop.

There were problems with the rule. The public/private distinction was shaky, especially in a writing workshop in which children continually talked and shared their writing in collaborative projects and peer conferences. According to Maya, she and Carol had already told Jil about The Zit Fit, and possibly James as well. This could have been done during class, on the playground, or on the way home from school.

So the rule could not stop children from hurting each other. In fact, one thing I realized in this case was how, if Jil somehow had been isolated from Maya’s story before, invoking the rule made her read the story. Jil’s control over her name was bought at this price. And this was placed against her hearing the story read in front of the class, or seeing it published in the classroom library.

There were two primary ways for children to go public with their texts: sharing time and the writing workshop library. My response to Maya’s text anticipated sharing time in at least two senses. First, I was talking to Maya just a few minutes before sharing time was to begin, and the conference was supposed to help Maya get ready for sharing. I had little time to read and figure out what should be done. Second, my response anticipated sharing time in the sense that I was worried about how children in the class--including Jil and James—would respond to Maya’s text. Sharing time was a public, teacher-sponsored event. My response to Maya’s text cannot be separated from my sense of responsibility for what happened there.

This deserves comment. Sharing time replaced the teacher at the front of the room with the child writer who read stories and solicited responses from peers. Grace and I encouraged and required children in the workshop to listen carefully to the texts shared by classmates. In this sense, we lent our institutional authority to the discourse of sharing time. In such situations, as Gilbert (1989) reminds us, children’s stories become part of the official curriculum of the classroom, and thus, are deserving of our scrutiny for what they are “teaching.” Maya wanted to share her text publicly in the writing workshop. That is what forced me to invoke the rule about names, and to worry about what Maya’s text might mean to her classmates.

In an ideal writing conference, as in Habermas’ (1970) ideal speech situation, we would expect an open-ended conversation between teacher and student in which various claims are raised and discussed, by both parties, in relation to the text at hand. The conference with Maya did not look much like this. I quickly decided that I could not allow Maya to read her text without Jil’s response and time for me to look at her text more closely. Most of the conference has me telling Maya what will happen: I told her Jil would read the text, that I would read the text, and that Maya could share tomorrow. There was little exploration of what Maya wanted to do with this piece, what she thought of it, or what help she needed. I attribute this to the time constraints I felt, to my determination that a classroom rule applied in this situation, and to my own struggle to figure out what the responsible thing to do was. My power as a teacher and adult enabled me to dominate the conference as I did.

We were working under severe time constraints, when perhaps more time was needed in order to unravel and work through what was for me a puzzling and emotionally charged text. When I decided that the rule about names was important in this situation, that also constrained my and Maya’s talk. One way it did this was by increasing the number of people who were involved in the situation, and whose perspectives would have to be taken into account. Instead of just Maya and me working something out between the two of us, I had decided that at least Jil and James needed to be in on the conversation, if not literally, then at least their interests considered. And in some sense, the function of the rule about names was to stop talk between the teacher and student, since the rule referred the question of whether or not a child’s name appeared in a story to another child. That is, the rule called for a conversation among children, not necessarily one between teacher and student. In my conference with Maya, I looked away from Maya and our discussion, in order to bring Jil into our conversation.

Finally, I faced a great deal of uncertainty in relation to the meaning of Maya’s text, and what I should do about it (beyond referring the question of names to children involved). I was faced with a text that drew on slippery, shifting things like social relations among children and local, timely meanings of words like “zits.” Furthermore, if I was correct that at least part of Maya’s intent was to hurt or tease other children, then it seems unlikely that our writing conference would be the place to expose and construct meaning in polite conversation. Maya would have good reason–given her knowledge of teacher disapproval of children hurting one another, and given her position of relatively little power in relation to me–to conceal, not reveal, possible meanings of her text; it would make sense for her to conceal her intention(s), rather than help me understand what her text and she were about.

That night, when I was no longer under the same time constraints or pressure to make a decision–when the situation was less “forced” (Scollan, 1988)–I could interact with and respond to Maya’s text in ways that I had not earlier in the day.

I hadn’t noticed at first that it is, formally, a fairly well-structured story. The boy/girl relationship sets up a series of problems that are eventually resolved with a man saving a woman and the woman getting a kiss (sounds like I should be objecting to this on feminist grounds as well). (Fieldnotes, 3-8-90)

I noticed how the story depended on the sorts of cultural knowledge I had anticipated questioning in my conception of response as socio-analysis. At the beginning of the story, there was the suggestion that a physical characteristic of Jil (acne), rather than, for example, her intelligence or courage, was what would make her attractive to the man of her choice. Later, against what her own experience told her, she believed Jake when he said that the fat boys would not beat her up. Jil did get beat up–this was a common occurrence, the author did not seem to take a moral stance against it, and Jil was unwilling or unable to fight back (something the third grade girls I worked with were usually quite able and willing to do in fights with each other and with their third grade male classmates). At the end, she was rescued (a little late, like in Charles Bronson movies) by Jake, and was kissed by him. There was much in Maya’s text (more than I have noted) that is “traditionally given in gender and identity” (Willinsky, 1990), and that could have become the focus of response and conversation.

But I did not pursue this line the next day in my second conference with Maya. I was more concerned about the immediate consequences for Jil and James of this story going public. I was also concerned about how to talk with Maya about this, since I anticipated violating a norm of the workshop that many children and I took quite seriously–student control over their own texts.

Maya sat back in her chair, arms at her sides, hands pressing against the seat of her chair. I tried to look at her, but sometimes had trouble looking her in the face. I was fairly sure my reading of her text was a good one, but I didn’t like confronting Maya about it. (Fieldnotes, 3-9-90)

I opened the conference with a sort of good news/bad news scenario. The good news was that the story had a good structure–it set up problems for the characters and resolved them by the end. The bad news:

LENSMIRE: The problem I have with it is this, it’s really mean. It’s really mean to the characters, it’s really mean to Jil. And she, she, she said that you can’t use her name in it. I think people–

MAYA: What am I supposed to do, use an alien’s name? It’s not fair. I want it to be somebody’s name in the class. (Audiotape, 3-9-90)

I had said what I thought the meaning of Maya’s text was for Jil and the class. Maya bristled. She returned to “I want it to be somebody’s name in the class” repeatedly in our conference. At the time, I could not figure this out. One guess now is that she was using the word “somebody” to say she wanted to keep Jil as the character’s name. In other words, it was a way of resisting my request that she take out Jil’s name. Another guess is that James, and not Jil, was a primary target of Maya’s text, and that she knew that in order for James to be properly teased by the story, there had to be a girl from the class in the other character’s position. In other words, Maya knew what James himself knew when he wrote his first Line Leader with Ken: She knew that she could provoke response by suggesting a romantic relationship between boys and girls in the room. Perhaps Maya had learned this in part from James and Ken. In order to involve James in such a provocative situation, a girl from the class was needed.

In the conference, I answered her by saying that the story would be hurtful to whomever she placed in Jil’s role. I listed the things that happened to the character–she liked zits, was embarrassed in class, beat up by boys–as reasons someone would not want to be that character. Finally, I asked her directly about her intentions, if she wanted to hurt someone’s feelings with the story.

MAYA: It’s just a story.

LENSMIRE: But what were you trying to do in this story? Why did you write that story?

MAYA: Because I liked it.

Maya answered and defended herself (and her text) against my questions with two short utterances that invoked powerful literary and workshop assumptions. Her first response, “It’s just a story,” points to the disjunction between author and material in fictional texts that I discussed in the last chapter. There, I emphasized how fiction lessened risks of personal exposure for authors, because readers of fiction could not assume that the author was expressing her own experiences or beliefs and values. But there is another consequence of the “distance” between authors and their material in fiction, one that Maya seemed to count on here. Britton (1982; again with quotes from Widdowson, 1975) provides part of Maya’s defense:

The literary writer, in fact … is “relieved from any social responsibility for what he says in the first person.” (Love letters … count as evidence in a court of law, love poems don’t!) (p. 158)

Maya did not write her story in first person, but with her first statement above, she asserted that her text was fictional, and by implication, that certain demands should not be made of it or her. It was just a story–she was not trying to tell about things that really happened to real people, so she should not be held accountable for lying or slandering. She was engaged in an acceptable sort of lying, and that lying included making up settings and characters and events. Maya had not written, to draw on Britton’s example above, a letter to a friend, or to Jil herself, in which she said all sorts of nasty things about her. From this angle, my questions for Maya were inappropriate–I wanted to connect her story too closely to real children and real feelings, and hold her responsible for the effects of her story in the classroom.

At the heart of our conflict at that moment in our second writing conference, was the status of Maya’s text in the world and her relationship to it. Maya and I represented two major opposing positions in literary theory on such questions, positions suggested by the traditional distinction between rhetoric and poetry:

Rhetoric and poetry, the text that means and the text that is, the text for persuasion and the text for contemplation. … (Scholes, 1985, p. 77)

My position was one that emphasized the participation of Maya’s text in the social life of the classroom. I asked Maya, “But what were you trying to do in this story?” I was emphasizing the rhetorical consequences of her text, and wanted to make sure she understood her text had effects on others. I aligned myself with literary theorists such as Bakhtin (1981), Said (1983), and others, who conceive of texts as “something we do, and indissociably interwoven with our practical forms of life” (Eagleton, 1983).

Maya’s position, expressed in, “It’s just a story,” removed her text from the social life of the classroom, and removed her social responsibility for her text. Her position has a long tradition–in Romanticism (Williams, 1983), as well as support from more recent literary theories such as New Criticism and certain versions of deconstruction (such as de Man, 1979). Here, texts are creations of imagination, self-referential and solitary objects, sites for the play of indeterminate meaning, removed from the struggles and responsibilities of everyday life:

At the center of the world is the contemplative individual self, bowed over its book, striving to gain touch with experience, truth, reality, history, or tradition. (Eagleton, 1983, p. 196)

Maya’s second comment, in response to my question as to why she wrote that story, requires less attention, not because it is less important, but because it assumed a commitment of writing workshop approaches that I have already developed in some detail–individual student control of texts. Maya justified her text by saying, “Because I liked it.” She asserted her right, in the writing workshop, to choose the texts she would write. In a setting in which children were encouraged to make their own individual choices, and the teachers worked to support student intention, Maya’s text (usually) would need little more justification for being written and shared than that she liked it. The workshop’s commitment to individual student intention, as Willinsky (1990) has shown, has roots in Romanticism. Thus, Maya’s first and second comments express different aspects of a “poetic” conception of texts, in which the texts authors write are abstracted from the contexts of their production and consumption.

Maya and I had reached an impasse. Maya was set on having the character’s name be someone in the class–this was her piece, she had the right to control it. And she wanted to share it. This was exactly what I felt I could not allow. I rejected the notion of Maya running from girl to girl in the class, looking for someone to take Jil’s place (if nothing else, making the text public that way).

LENSMIRE: Well, I’m not going to let you share that story as it is right now, because I’m afraid it would hurt people’s feelings. But if you want to try to make changes to it that you think would make it better, that way, you can, okay? Or, you can find, I know you have a lot of other stories, because you write a lot. So what are you going to do? What do you want to do?

MAYA: I have to change the name. I suppose I have to change the name.

Maya said this slowly and grudgingly. She gave in to me–I do not believe she had been persuaded–and agreed to not name the character after Jil or other children in the class. I talked to her about the first part, about the zits. Maya told me that Carol had named it The Zit Fit, so I told her that she could just name it something else then and change the first part. I ignored the other aspects of the text I found questionable; I even said that the rest of the story was fine, which was not necessarily true. I wish I could say that I had made a well-reasoned decision that we had dealt with enough for now, but I just forgot. Maya did not look too pleased as she left the table; I did not feel too happy myself.

The story is not over, but not because Maya continued to pursue this text. The next time I conferenced with her, she was working on a text describing a game she and her brother played together. It was Carol’s turn.

Alongside each utterance … off-stage voices can be heard. (Barthes, 1974)

After Maya and I finished our conference, I worked at the round table. I looked up when I heard Carol, two rows over from me with Maya just behind her, almost shouting at me, “That’s unfair!” She said this several times before I understood what she was talking about. Then she said, “It’s just a name.” I ignored her and looked back at my work.

The next Monday, I overheard Carol and Maya attempting to enlist their regular teacher, Grace, on their side. Carol told Grace that Maya should be allowed to use Jil’s name in the story. Grace left them and walked over to me. Before Grace got to me, Carol called out after her, “Jil is a popular name.” Grace told me that she had told them they had to respect their classmates. I told Grace that I wanted the same thing. While we were talking, Carol said, “Okay, then we’ll just put it backwards–LIJ.” Carol and Maya continued talking, just loud enough for Grace and me to hear, and probably Jil as well, who sat a few feet behind them. They seemed to be accomplishing orally what I was not allowing them to do with Maya’s written text.

Tuesday:

The Carol and Maya “It’s just a name” saga continues. Today the attack shifted. Somewhere in here, Carol and Maya noticed that Jil had written on Maya’s text–“change the name from me.” Now Carol said, “How dare Jil write on Maya’s paper” (she actually said, “How dare.”) She was about three or four feet away from me, arms at her side, fists clenched, with a lot of indignation on her face, body slightly bent forward from the waist. I didn’t get it right away, but I soon realized what she was talking about.Today I took her on. I told her that I wasn’t going to back down. That it was a classroom rule that people could take their names out of other people’s stories before the stories went public. Carol responded that it still was not right for Jil to write on Maya’s paper. I told her that I had asked Jil to respond, she had, and that it wouldn’t happen that way again. She said it still wasn’t right. As she walked away, she said that Jil wasn’t the nice person we teachers thought she was, “not such a nice person at all.” But she seemed somewhat subdued. Maybe from my tone of voice she realized that I was serious. (Fieldnotes. 3-9-90)

Whatever purposes Carol had for arguing with me, she assumed that a student’s text was her private possession. She assumed student ownership. And she used this norm as a resource to argue with me–how dare Jil write on Maya’s paper. Graves (1981) had introduced his concept of student ownership with a little story about how renters and owners acted differently toward the houses in which they lived–owners took better care of them. He believed student ownership of texts resulted in better quality products because, like homeowners, students who owned their texts would care for them more, in the crafting of their material and their attention to surface features. Apparently, Carol and Maya looked upon Jil’s comment, written in the margin of Maya’s paper, as an unsightly bit of graffiti. In any event, this was the last time Carol confronted me about this issue. Conferences with Carol about her work seemed, to me at least, largely unaffected by all this. Carol continued writing long texts and talking with me regularly.

I talked with Maya’s mother, Lauren, at parent-teacher conferences at the end of March. I knew Lauren better than most of the other parents–for the first few months of school, Lauren had helped children put together and publish their books in the workshop. We had had the chance to talk about what I was trying to do in my teaching, and Lauren responded positively to what I said and what she saw happening in the classroom. During our conference, I told Lauren that Maya and I had had a run-in over a text I thought would be hurtful to others. Lauren’s response was supportive. She told me that she had been concerned, after talking with me about writing workshop approaches, that children would be granted control over their writing without taking on any responsibility for what they wrote. Her only question for me was, did Maya understand why I had questioned her piece? I told Lauren that I had talked with Maya about how I thought her story would hurt other children’s feelings.

But Lauren’s question cannot be answered quite as simply as I answered it that night. If by “understand” we mean something approaching Habermas’ (1984, 1987) notion of reaching agreement, I doubt that Maya understood. I depended, ultimately, on my institutional authority to settle what would happen. I had begun questioning student intention and material with Maya, and she and Carol questioned my intervention in Maya’s writing. But the process was most likely terminated long before Maya and I had talked enough to explain ourselves to each other.

I do not want to imply, however, that all difficulty in this case arose from complexity and misunderstanding–that if only we had had the time and the knowledge, everything would have run along smoothly. This story was also about a conflict of wills and beliefs and values. I think that, in some ways, Maya and Carol and I understood each other quite well, that Maya understood my concerns about her story, but rejected the normative claim I was making that it was not all right to share that sort of story. And if her intentions were not entirely honorable, then she had reasons for hiding those intentions and not engaging me in an open discussion of her text.

I acted to keep a text that I decided would be hurtful to other children from going public. My response was caught up in questions of how we should treat one another, who gets to tell whose stories, and social relations among children. I decided that following the child would be morally and politically irresponsible.

But response as socioanalysis suffered here as well, for at least two reasons. First, the commitment to looking to the past, to addressing the distorted stories children bring with them from outside the classroom, ignores the life, the culture in which children participate in schools. Maya’s text included material worth examining for what it said about women and their relations to men in our society. But in this case, the immediate relations among children were more pressing. Second, the powerful image of response as an intimate, isolated conversation, involving two people and a text, ignores all the ways teacher response itself participates in the social life of the classroom. In this instance, my response to Maya’s text included conversations with Jil, Carol, Maya’s mother, and Grace; it responded to a text written by Suzanne and the teasing Jessie encountered; it drew on readings of who children were to each other, and classroom norms; and it anticipated the responses of future readers of Maya’s texts, as well as Maya’s responses to what I said.

I have tried to suggest throughout my discussion the tentativeness of my interpretation of this case and the meanings of what people said and did. If things were tentative here, they were even more so while I was teaching, and that was an important problem in this occasion for response. My decision to not follow Maya’s lead represented a fairly hard stand on soft ground. Following the child would have been easier; treating the text as a cultural artifact of American society would have been easier. Reading and responding to Maya’s text in relation to this particular context was much harder.