5. Adaptive Immunity

Antigens and the Adaptive Immune Response

Adaptive immunity occurs after exposure to an antigen either from a pathogen or a vaccination.The adaptive, or acquired, immune response takes days or even weeks to become established—much longer than the innate response; however, adaptive immunity is more specific to an invading pathogen. This part of the immune system works in tandem with the innate immune response to neutralize pathogens. In fact, without information from the innate immune system, the adaptive response could not be mobilized.

An antigen is a small, specific molecule on a particular pathogen that stimulates a response in the immune system. One example of an antigen is a specific sequence of 8 amino acids in a protein found only in an influenza virus, the virus responsible for causing “the flu.”. Another example is a short chain of carbohydrates found on the cell wall of Neisseria meningitidis, the bacteria that causes meningitis. There are millions of potential sequences of amino acids, carbohydrates, and other small molecules that can act as antigens. The adaptive immune system works because the immune cells responsible for it are each able to recognize and respond to one specific antigen, or a few very similar ones.

The adaptive immune responses depends on the function of two types of lymphocytes, called B cells and T cells. In adaptive immunity, activated T and B cells whose surface binding sites are specific to the antigen molecules on a pathogen greatly increase in numbers and attack the invading pathogen. Their attack can kill pathogens directly or they can secrete antibodies that enhance the phagocytosis of pathogens and disrupt the infection. Adaptive immunity also involves a memory to give the host long-term protection from reinfection with the same type of pathogen carrying the same antigens; on reexposure, this host memory will facilitate a rapid and powerful response.

*

B and T Cells

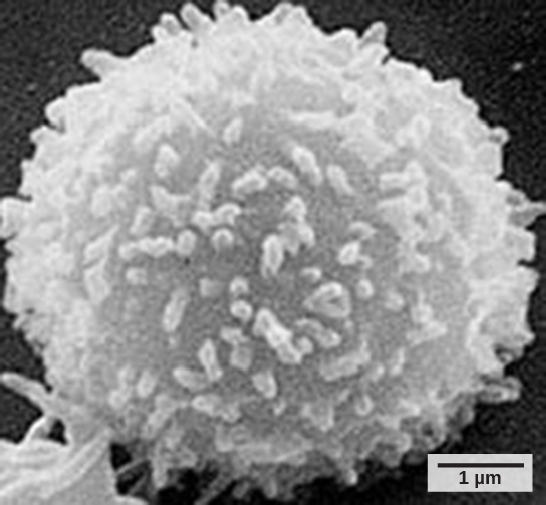

Lymphocytes, which are a subclass of white blood cells, are formed with other blood cells in the red bone marrow found in many flat bones, such as the shoulder or pelvic bones. The two types of lymphocytes of the adaptive immune response are B and T cells (Figure 1). Whether an immature lymphocyte becomes a B cell or T cell depends on where in the body it matures. The B cells remain in the bone marrow to mature (hence the name “B” for “bone marrow”), while T cells migrate to the thymus, where they mature (hence the name “T” for “thymus”). During the maturation process, each B or T cell develops unique surface proteins that are able to recognize a unique set of very specific molecules on antigens (discussed below). In other words, each B or T cell can recognize only a very few different molecules, but together the entire lymphocyte population in a healthy person should be able to recognize molecules from most pathogens. The specificity of these unique surface proteins, or receptors, on the lymphocytes is determined by the genetics of the individual and is present before a foreign molecule is introduced to the body or encountered. Except in certain immune system diseases called autoimmune diseases, no mature B or T cells are able to recognize and bind to molecules that are found on healthy human cells, but only to molecules found on pathogens or on unhealthy human cells.

B cells are involved in the humoral immune response, which targets pathogens loose in blood and lymph, and B cells carry out this response by secreting antibodies.T cells are involved in the cell-mediated immune response, which targets infected cells in the body. T cells include the Helper T cells and the Cytotoxic, or Killer, T cells. Cytotoxic T cells directly kill human cells that are infected or unhealthy. Helper T cells do not directly kill infected cells, but secrete molecules that are crucial for the function of all other cells in the immune response to a pathogen.

*

Four Stages of the Adaptive Immune Response

B cells, Helper T cells, and Cytotoxic T cells all respond to antigens in a similar pattern; subsequent sections of this chapter will address the specifics of the immune response in each cell type. In order for their immune functions to be elicited, the cells must first encounter antigens by binding specifically to them using specialized membrane proteins. This binding elicits changes in the activity of the immune cells, termed activation, which is the second step in the adaptive immune response. Activation responses vary between the three types of cells, but in general all involve both changes in gene expression and in the initiation of cell division. Third, the immune cells attack invading pathogens or infected cells. Depending on the type of lymphocyte, the specific methods used to neutralize pathogens can vary. In most infections, the attacks from many different lymphocytes, and from cells of the innate immune system, occur simultaneously and the atttacking cells often stimulate each other through chemical messenger such as cytokines. Finally, long-lived, pre-activated immune cells that wait for a subsequent infection are formed in the memory phase of the adaptive immune response. These cells are identical to the initial cells that first encountered the pathogen except that they have already undergone the activation step so are able to attack right away when activated again by an antigen.

Humoral Immune Response: B cells

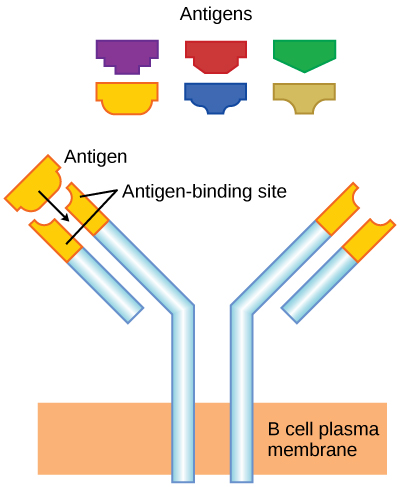

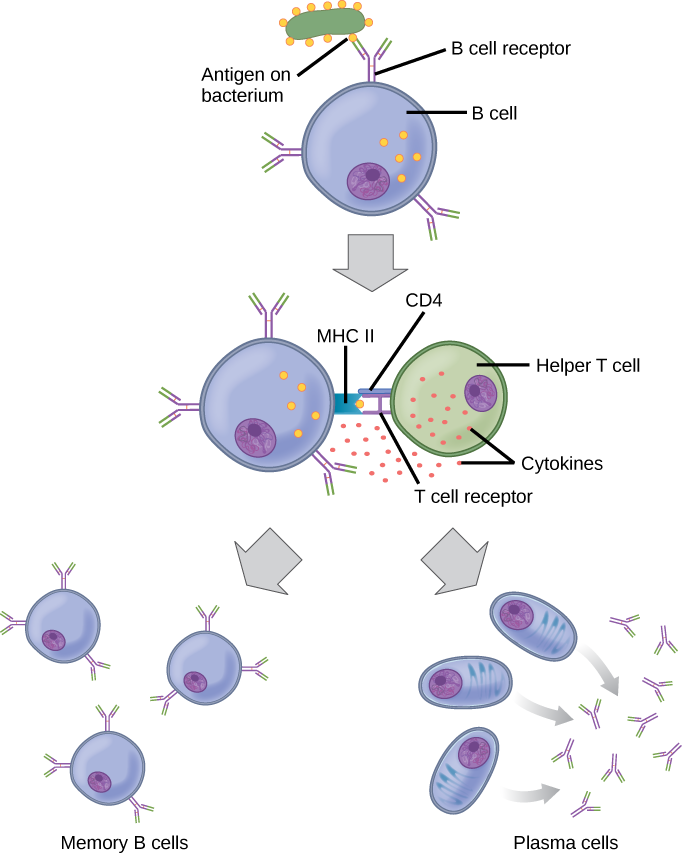

As mentioned, an antigen is a molecule that stimulates a response in the immune system. B cells participate in a chemical response to antigens present in the body by producing specific antibodies that circulate throughout the body and bind with an antigen whenever it is encountered. This is known as the humoral immune response because it involves molecules secreted into the blood plasma, an acellular fluid or “humor.” As discussed, during maturation of B cells, a set of highly specific B cells are produced, each with antigen receptor molecules in their membrane (Figure 2).

Each B cell has only one kind of antigen receptor, which makes every B cell different. Once the B cells mature in the bone marrow, they migrate to lymph nodes or other lymphatic organs, where they wait to encounter potential antigens. When a B cell encounters the antigen that binds to its receptor, the antigen molecule is brought into the cell, where it is processed by the cell, and reappears on the surface of the cell bound to B cell protein. When this process is complete, the B cell is considered to be activated.

Activation induces the B cell to divide rapidly, which makes thousands of identical (clonal) cells. These cells become either plasma cells or memory B cells. The memory B cells remain inactive at this point, until another later encounter with the antigen, caused by a reinfection by the same bacteria or virus, results in them dividing into a new population of plasma cells to carry out the memory phase of the B cell response. The plasma cells, on the other hand, produce and secrete large quantities, up to 100 million molecules per hour, of antibody molecules. An antibody, also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a protein that is produced by plasma cells after stimulation by an antigen. Antibodies are the agents of humoral immunity; they are the weapons the B cells use in their attacks on pathogens. Antibodies occur in the blood, in gastric and mucus secretions, and in breast milk. Antibodies in these bodily fluids can bind pathogens and mark them for destruction by phagocytes before they can infect cells.

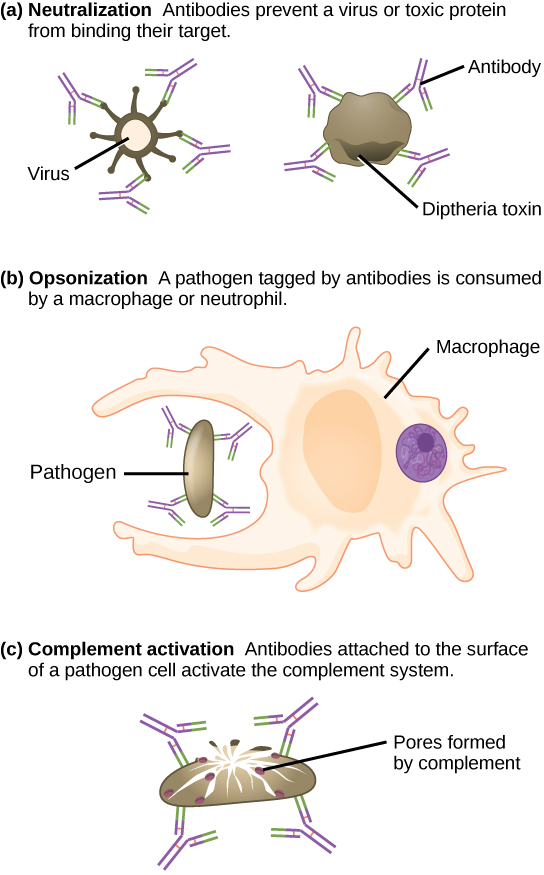

These antibodies circulate in the blood stream and lymphatic system and bind with the antigen whenever it is encountered. The binding can fight infection in several ways. Antibodies can bind to viruses or bacteria and interfere with the chemical interactions required for them to infect or bind to other cells. The antibodies may create bridges between different particles containing antigenic sites clumping them all together and preventing their proper functioning. The antigen-antibody complex stimulates the complement system described previously, destroying the cell bearing the antigen. Phagocytic cells of the innate immune system are attracted by the antigen-antibody complexes, and phagocytosis is enhanced when the complexes are present. Finally, antibodies stimulate inflammation, and their presence in mucus and on the skin prevents pathogen attack.

The production of antibodies by plasma cells in response to an antigen is called active immunity and describes the host’s active response of the immune system to an infection or to a vaccination. There is also a passive immune response where antibodies come from an outside source, instead of the individual’s own plasma cells, and are introduced into the host. For example, antibodies circulating in a pregnant female’s body move across the placenta into the developing fetus. Antibodies are also passed to the child in breast milk. The child benefits from the presence of these antibodies for up to several months after birth. In addition, a passive immune response is possible by injecting antibodies into an individual in the form of an antivenom to a snake-bite toxin or antibodies in blood serum to help fight a hepatitis infection. This gives immediate protection since the body does not need the time required to mount its own response.

*

Cell-Mediated Immunity: T cells

Activation of T cells also begins when T cells encounter antigens and bind to them with specific proteins on their cell surfaces, called T cell receptors. Each T cell’s receptor proteins are able to bind to only one or a few very similar antigens, allowing each one to respond to different pathogens. Unlike B cells, T lymphocytes are unable to recognize pathogens without assistance. They rely on cells of the innate immune system to help them encounter antigens, and to start the responses required for an immune attack, in a complex process that is beyond the scope of this textbook. T cells that have encountered antigens that bind to their specific receptors in this process, and received important signals from the innate immune cells are considered to be “activated.

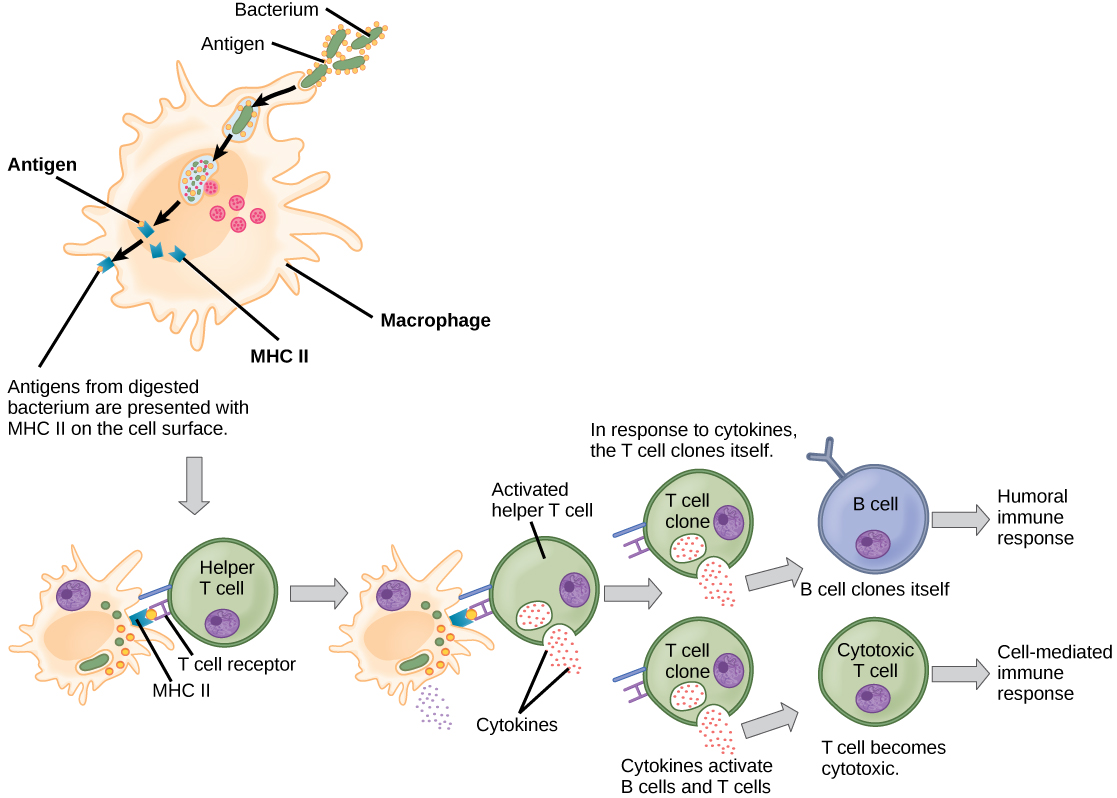

There are two main types of T cells: Helper T cells (sometimes called TH) and Cytotoxic T cells (TC, also known as killer T cells.) The Helper T cells function indirectly to tell other immune cells about potential pathogens. After encountering an antigen, a Helper T cell’s activation causes many rounds of cell division to occur, producing thousands of identical cells that all have the same T cell receptor and all have initiated the expression of genes required for producing and secreting cytokines. As with B cells, the clone includes active TH cells and inactive memory TH cells. Helper T cells carry out their attacks on pathogens through the secretion of these cytokines. These chemical messengers greatly enhance the activities of macrophages, innate immune cells and Cytotoxic T cells, and also stimulate naïve B cells to secrete antibodies. A summary of how the humoral and cell-mediated immune responses are activated appears in Figure 4. Similar to memory B cells, memory Helper T cells are long-lived, and can carry out a fast response to the same pathogen after decades.

*

Immunological Memory

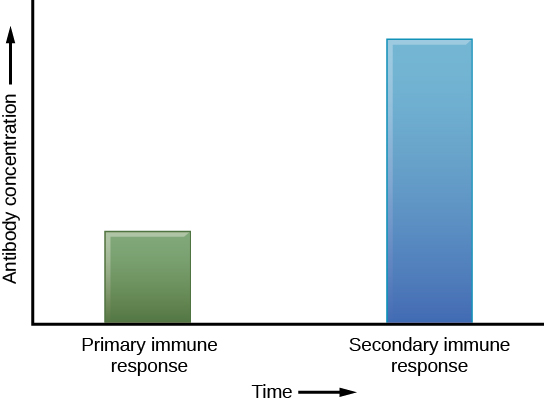

The adaptive immune system has a memory component that allows for a rapid and large response upon reinvasion of the same pathogen. During the adaptive immune response to a pathogen that has not been encountered before, known as the primary immune response, plasma cells secreting antibodies and differentiated T cells increase, then plateau over time. As B and T cells mature into effector cells, a subset of the naïve populations differentiates into B and T memory cells with the same antigen specificities (Figure 5). A memory cell is an antigen-specific B or T lymphocyte that does not differentiate into an effector cell during the primary immune response, but that can immediately become an effector cell on re-exposure to the same pathogen. As the infection is cleared and pathogenic stimuli subside, the effectors are no longer needed and they undergo apoptosis. In contrast, the memory cells persist in the circulation.

If the pathogen is never encountered again during the individual’s lifetime, B and T memory cells will circulate for a few years or even several decades and will gradually die off, having never functioned as effector cells. However, if the host is re-exposed to the same pathogen type, circulating memory cells will immediately differentiate into plasma cells and active Helper T cells without requiring the help of innate cells, or cytokines from activated Helper T cells. This is known as the secondary immune response. One reason why the adaptive immune response is delayed is because it takes time for naïve B and T cells with the appropriate antigen specificities to be identified, activated, and proliferate. On reinfection, this step is skipped, and the result is a more rapid production of immune defenses. Each of these newly reactivated effector cells also produces a stronger response than the first set of effector cells. For example, memory B cells that differentiate into plasma cells in a secondary immune response output tens to hundreds-fold greater antibody amounts than were secreted during the primary response (Figure 6). This rapid and dramatic antibody response may stop the infection before it can even become established, and before the innate immune system can initiate the inflammatory response that causes symptoms of infection such as fever, redness, swelling and body aches. The individual may not even realize they had been exposed to the pathogen.

Vaccination is based on the knowledge that exposure to noninfectious antigens, derived from known pathogens, generates a mild primary immune response. Vaccines usually contain either weakened or dead microbes, or fragments of molecules found on pathogens that are known to contain antigens. The also usually contain molecules that stimulate the innate response, since innate immune responses are important in the generation of strong adaptive responses. The immune response to vaccination may not be perceived by the host as illness but still confers immune memory. When exposed to the corresponding pathogen to which an individual was vaccinated, the reaction is similar to a secondary exposure. Because each reinfection generates more memory cells and increased resistance to the pathogen, some vaccine courses involve one or more booster vaccinations to mimic repeat exposures.

*

Section Summary

The adaptive immune response is a slower-acting, longer-lasting, and more specific response than the innate response. However, the adaptive response requires information from the innate immune system to function. The adaptive immune response in B cells, Helper T cells and Cytotoxic T cells involved four phases: encounter, activation, attack, and memory. in this response, activated T cells differentiate and proliferate, becoming Helper (TH) cells or Cytotoxic (TC) cells. Helper T cells cells stimulate B cells, Cytotoxic T cells, and innate immune cells to enhance their attacks on pathogens. B cells differentiate into plasma cells that secrete antibodies, whereas Cytotoxic T cells destroy infected or cancerous cells. Memory cells are produced by activated and proliferating B and T cells and persist after a primary exposure to a pathogen. If re-exposure occurs, memory cells differentiate into effector cells without input from the innate immune system. Vaccination works by eliciting a primary immune response, without exposure to pathogens that could cause disease.

*

Glossary

- active immunity

- an immunity that occurs as a result of the activity of the body’s own cells rather than from antibodies acquired from an external source

- adaptive immunity

- a specific immune response that occurs after exposure to an antigen either from a pathogen or a vaccination

- antibody

- a protein that is produced by plasma cells after stimulation by an antigen; also known as an immunoglobulin

- antigen

- a macromolecule that reacts with cells of the immune system and which may or may not have a stimulatory effect

- B cell

- a lymphocyte that matures in the bone marrow

- cell-mediated immune response

- an adaptive immune response that is controlled by T cells

- cytotoxic T lymphocyte (TC)

- an adaptive immune cell that directly kills infected cells via enzymes, and that releases cytokines to enhance the immune response

- effector cell

- a lymphocyte that has differentiated, such as a B cell, plasma cell, or cytotoxic T cell

- helper T lymphocyte (TH)

- a cell of the adaptive immune system that binds APCs via MHC II molecules and stimulates B cells or secretes cytokines to initiate the immune response

- humoral immune response

- the adaptive immune response that is controlled by activated B cells and antibodies

- lymph

- the watery fluid present in the lymphatic circulatory system that bathes tissues and organs with protective white blood cells and does not contain erythrocytes

- memory cell

- an antigen-specific B or T lymphocyte that does not differentiate into an effector cell during the primary immune response but that can immediately become an effector cell on reexposure to the same pathogen

- passive immunity

- an immunity that does not result from the activity of the body’s own immune cells but by transfer of antibodies from one individual to another

- primary immune response

- the response of the adaptive immune system to the first exposure to an antigen

- secondary immune response

- the response of the adaptive immune system to a second or later exposure to an antigen mediated by memory cells

- T cell

- a lymphocyte that matures in the thymus gland

-

-

-

-

- CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

- OpenStax, Concepts of Biology, Section 17.3 Adaptive Immunity

Provided by: Rice University

Access for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/concepts-biology

License: CC-BY 4.0

Adapted By: Kristina Prescott Sarah Malmquist

-

-

-