8. Translation

The synthesis of proteins is one of a cell’s most energy-consuming metabolic processes. In turn, proteins account for more mass than any other component of living organisms (with the exception of water), and proteins perform a wide variety of the functions of a cell. The process of translation, or protein synthesis, involves decoding an mRNA message into a protein product. Amino acids are strung together in lengths ranging from approximately 50 amino acids to more than 1,000.

*

The Protein Synthesis Machinery

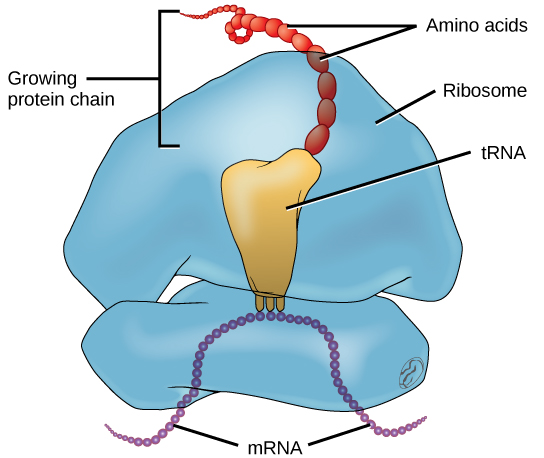

In addition to the mRNA template, many other molecules contribute to the process of translation. The composition of each component may vary across species; for instance, ribosomes may consist of different numbers of ribosomal RNAs (rRNA) and polypeptides depending on the organism. However, the general structures and functions of the protein synthesis machinery are comparable from bacteria to human cells. Translation requires the input of an mRNA template, ribosomes, tRNAs, and various enzymatic factors (Figure 1).

A ribosome is a complex macromolecule composed of structural and catalytic rRNAs, and many distinct proteins. Ribosomes are located in the cytoplasm and endoplasmic reticulum of animal cells. Each mRNA molecule is simultaneously translated by many ribosomes, all synthesizing protein in the same direction. Ribosomes are made up of a large and a small subunit that come together for translation. The small subunit is responsible for binding the mRNA template, whereas the large subunit sequentially binds tRNAs, a type of RNA molecule that brings amino acids to the growing chain of the polypeptide.

Serving as adaptors, specific tRNAs bind to sequences on the mRNA template and add the corresponding amino acid to the polypeptide chain. Therefore, tRNAs are the molecules that actually “translate” the language of RNA into the language of proteins. For each tRNA to function, it must have its specific amino acid bonded to it. In the process of tRNA “charging,” each tRNA molecule is bonded to its correct amino acid.

*

The Genetic Code

To summarize the last chapter, the cellular process of transcription generates messenger RNA (mRNA), a mobile molecular copy of one or more genes with an alphabet of A, C, G, and uracil (U). Translation of this mRNA template converts nucleotide-based genetic information into a protein product. Protein sequences consist of 20 commonly occurring amino acids; therefore, it can be said that the protein alphabet consists of 20 letters. Each amino acid is defined by a three-nucleotide sequence called the triplet codon. The relationship between a nucleotide codon and its corresponding amino acid is called the genetic code.

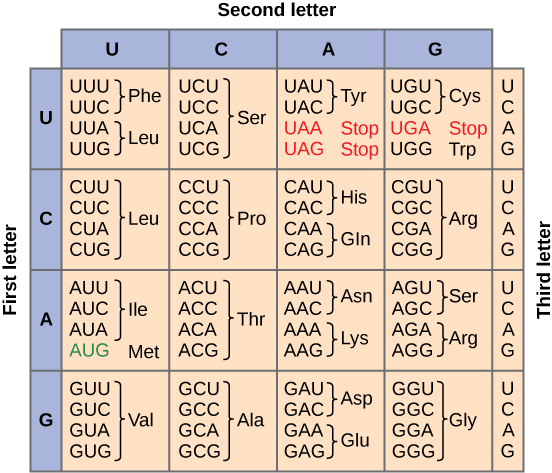

Given the different numbers of “letters” in the mRNA and protein “alphabets,” combinations of nucleotides corresponded to single amino acids. Using a three-nucleotide code means that there are a total of 64 (4 × 4 × 4) possible combinations; therefore, a given amino acid is encoded by more than one nucleotide triplet. A table of the amino acids encoded by each triplet, called a Codon Table, is shown in Figure 2.

Three of the 64 codons terminate protein synthesis and release the polypeptide from the translation machinery. These triplets are called stop codons. Another codon, AUG, also has a special function. In addition to specifying the amino acid methionine, it also serves as the start codon to initiate translation. This codon signals to the the parts of the translation machinery to begin adding amino acids, and also recruits a tRNA carrying the amino acid methionine, abbreviated Met on the codon table above. Because of this, all newly . synthesized proteins start with the amino acid methionine. The reading frame for translation is set by the AUG start codon near the 5′ end of the mRNA. The genetic code is universal. With a few exceptions, virtually all species use the same genetic code for protein synthesis, which is powerful evidence that all life on Earth shares a common origin.

*

The Mechanism of Protein Synthesis

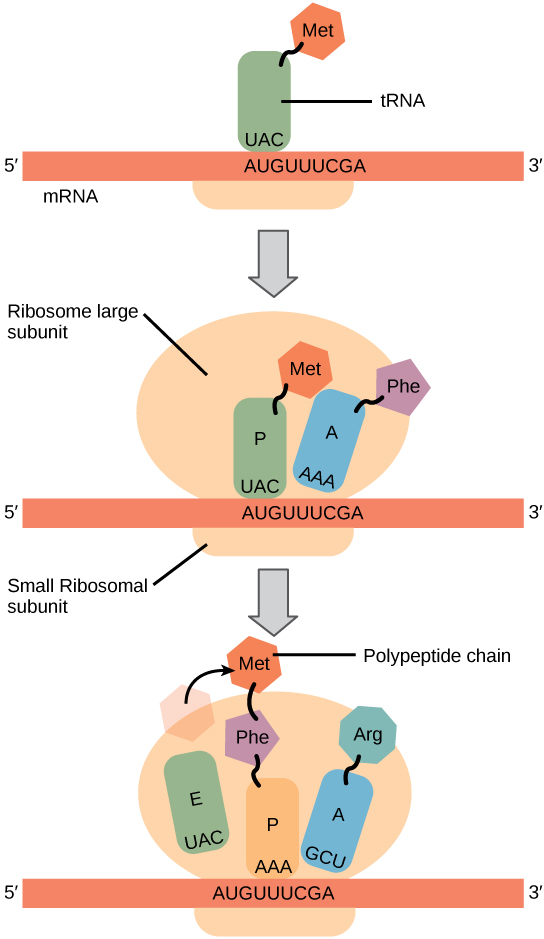

Just as with mRNA synthesis, protein synthesis can be divided into three phases: initiation, elongation, and termination. The process of translation is similar in most cells, in most species. Protein synthesis begins with the formation of an initiation complex. In E. coli, this complex involves the small ribosome subunit, the mRNA template, three initiation factors, and a special initiator tRNA. The initiator tRNA interacts with the AUG start codon, and links to a special form of the amino acid methionine that is typically removed from the polypeptide after translation is complete.

The elongation phase of translation involves the large ribosomal subunit. The large ribosomal subunit of E. coli consists of three compartments: the A site binds Arriving charged tRNAs (tRNAs with their attached specific amino acids). The P site binds charged tRNAs carrying amino acids that have formed bonds with the growing Protein chain but have not yet dissociated from their corresponding tRNA. The E site releases dissociated tRNAs so they can exit and be recharged with free amino acids. The ribosome shifts one codon at a time, catalyzing each process that occurs in the three sites. With each step, a charged tRNA enters the complex, the polypeptide becomes one amino acid longer, and an uncharged tRNA departs(Figure 3).

Termination of translation occurs when a stop codon (UAA, UAG, or UGA) is encountered. When the ribosome encounters the stop codon, the growing polypeptide is released and the ribosome subunits dissociate and leave the mRNA. After many ribosomes have completed translation, the mRNA is degraded so the nucleotides can be reused in another transcription reaction.

Concept in Action

*

Section Summary

The central dogma describes the flow of genetic information in the cell from genes to mRNA to proteins. Genes are used to make mRNA by the process of transcription; mRNA is used to synthesize proteins by the process of translation. The genetic code is the correspondence between the three-nucleotide mRNA codon and an amino acid. The genetic code is “translated” by the tRNA molecules, which associate a specific codon with a specific amino acid. The genetic code is degenerate because 64 triplet codons in mRNA specify only 20 amino acids and three stop codons. This means that more than one codon corresponds to an amino acid. Almost every species on the planet uses the same genetic code.

The players in translation include the mRNA template, ribosomes, tRNAs, and various enzymatic factors. The small ribosomal subunit binds to the mRNA template. Translation begins at the initiating AUG on the mRNA. The formation of bonds occurs between sequential amino acids specified by the mRNA template according to the genetic code. The ribosome accepts charged tRNAs, and as it steps along the mRNA, it catalyzes bonding between the new amino acid and the end of the growing polypeptide. The entire mRNA is translated in three-nucleotide “steps” of the ribosome. When a stop codon is encountered, a release factor binds and dissociates the components and frees the new protein.

*

Glossary

- codon

- three consecutive nucleotides in mRNA that specify the addition of a specific amino acid or the release of a polypeptide chain during translation

- genetic code

- the amino acids that correspond to three-nucleotide codons of mRNA

- rRNA

- ribosomal RNA; molecules of RNA that combine to form part of the ribosome

- stop codon

- one of the three mRNA codons that specifies termination of translation

- start codon

- the AUG (or, rarely GUG) on an mRNA from which translation begins; always specifies methionine

- tRNA

- transfer RNA; an RNA molecule that contains a specific three-nucleotide anticodon sequence to pair with the mRNA codon and also binds to a specific amino acid

-

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

OpenStax, Concepts of Biology, Section 9.4 Translation

Provided by: Rice University

Access for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/concepts-biology

License: CC-BY 4.0

Adapted By: Sarah Malmquist