Chapter 8 – Innovations and Trend Forecasting

Gozde Goncu Berk

The term trend has been used to refer to a change in opinions, attitudes, behaviors, expectations, or general patterns within a society. Being able to detect and reflect on these changes is the core of the trend forecasting process. Mason et al. (2015) defined the three fundamental and interacting elements that cause a trend to emerge: 1) basic human needs, 2) drivers of change, and 3) innovations.

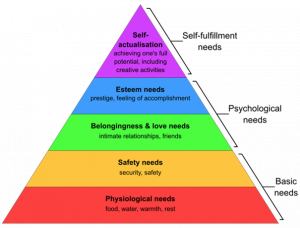

Basic needs are fundamental to all humans. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (1943) includes physiological needs such as food, water, and rest, and safety needs such as environmental protection and security. Once an individual satisfies their needs at the bottom of the “needs pyramid,” they will try to satisfy other needs and wants at the higher levels, such as the psychological need for belongingness and love, along with self-esteem and self-fulfillment needs. Monitoring pattern shifts on the levels of a population’s basic needs and its in-between need levels can help a forecaster identify emerging trends. The Covid-19 pandemic, for example, triggered an immediate and sudden shift to lower-level needs like safety, protection, and food. Basic face masks were in high demand when people first sought protection from the virus. As people adjusted to the new norms of the pandemic, face masks evolved into fashion statement pieces instead of being only a medical necessity. We started seeing masks with colorful prints and patterns, embroidered statements, or designer brand logos, with such options fulfilling higher-level desires.

Drivers of change can be slow, long-term macro changes that take place over a long period of time, such as the aging of a population, or faster and more immediate changes such the creation of a new technology, an economic crisis, a political shift, or an environmental incident. Futurist Patrick Dixon (2015) defines long-term trends as relatively more predictable in long-range forecasting. Some of the profound long-term megatrends he identifies are gradual falling rates of growth in world population; more automation of routine tasks in homes, offices and factories; and increasing concern about the environment.

We can see the impacts of these macro trends in the fashion design industry and beyond. Many fashion brands, for example, market collections designed for older populations, factory robots cut and sew fabric, artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms predict style trends, and virtual reality (VR) mirrors display a user’s image on a screen with virtual clothing automating, personalizing, and speeding up the fashion space. Environmental concerns are reflected in the use of biodegradable textiles such as the vegan leather made from pineapple leaf fibers (ananas-anam.com). Faster and more immediate changes are less predictable, but can also translate quickly into trends. As people shifted to remote work and distance learning during the Covid 19 pandemic, virtual meeting platforms became popular not only for work-related activities but for online playdates, birthdays, and family reunions. Fashion stylists and designers started giving advice on how to dress for “waist-up” online meetings, emphasizing bright colors, bold patterns, and form-fitting tops. Chapter Five, “Trend Drivers and Megatrends,” provide a detailed discussion of the factors that trigger change and trends.

Innovations that shift people’s behaviors, needs, and wants can lead to new trends, which can then springboard other related innovations.

Innovations that shift people’s behaviors, needs, and wants can lead to new trends, which can in turn springboard other related innovations. Innovations can include novel products, services, or processes that lead to new user experiences.

As we’ve discussed, trend research and forecasting is a complex process that requires far more than spotting the latest styles, colors, or hi-tech gadgets. It requires in-depth, structured research and analysis to make educated guesses about the future. Mason et al. (2015) introduces a layered framework for forming trend insights that can help you understand where to look for changes in pattern. At the top layer are the megatrends—the large social, economic, political, environmental, or technological changes that are slow to form that but affect people on many scales and across many industries (Goncu-Berk, 2015). On the middle layer are the individual trends, which are supported by the clusters of innovations that sit on the bottom layer. When new innovations don’t fit existing patterns and start to cluster around a new trend, or when changes on the macro level start to point in a new direction, they signal emergence of a new trend. Monitoring changes in macro-level long-term developments and innovations is therefore crucial in detecting the emergence of a new trend as well in evaluating the lifecycle of existing trends and their diffusion within a society.

Invention, Design and Innovation

While the terms invention, design, and innovation are often used interchangeably, they have quite distinct meanings. Before proceeding further, it is worthwhile to clarify these and other related terms.

An invention is “a novel scientific or technical idea that is transformed into reality, achieving a completely unique function or result.” It is a radical breakthrough, usually in technology. One example from in fashion is VELCRO®, invented by engineer George de Mestral. He mimicked the hooks of the burrs trapped in his dog’s fur, and named his invention after the French words for velvet and hook (velours and crochet). Today, VELCRO® is a versatile product used in everything from apparel to packaging and medical industries.

Product design is “The activity in which ideas and needs are given physical form, initially as solution concepts and then as a specific configuration or arrangement of elements, materials and components” (Walsh et al., 1993, p. 18). Unlike invention, product design does not imply a radical breakthrough, but instead entails improvement of functionality and appeal to create novel product ideas which may address unsatisfied user or market needs. Mamalila, a German company which offers a versatile, convertible jacket for different phases of parenthood, is a good example of novel design. The Mamalila jacket does not offer any superior technology compared to readily available outdoor jackets, but it targets a latent user need and improves functionality and appeal need through a novel design feature. Design that is induced by unsatisfied user need is defined as market-pull, referring to the need for a solution to a user problem stemming from the users themselves or, in other words, the marketplace.

New technologies and inventions can also inspire design and lead to novel product ideas. When design is induced by technological and technical advancements or inventions, it is called technology-push. In this approach the technology provides a clear competitive advantage in meeting the user need, and alternative technologies are unavailable or very difficult to utilize. Tyvek®, for example, is a nonwoven textile material of high-density polyethylene fibers. It is extremely durable, lightweight, and breathable, and is also water resistant. These properties have made Tyvek® especially useful in construction applications like house wraps for insulation. The designers of UT.LAB benefited from the properties of Tyvek® in their design of fashionable and functional sneakers, pre-wrinkling the material for better fit and comfort, and using a unique printing technique to print patterns on the material.

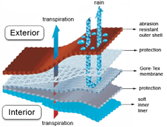

Another example technology-push in product design is GORE-TEX, a textile material originally used in the design of outdoor apparel because of its combined waterproof, windproof, and breathable characteristics. The properties of GORE-TEX technology have made it suitable for medical application in the design of vascular prosthetics.

As with technology-push, designers of platform products assume a product will embody a particular technology platform. Platform products are built around a preexisting technological system or a platform, such as the Mac operating system OS X. With large investments made to develop these platforms, they are incorporated into as many products as possible. For example, Nike Dri-FIT technology, for example, features microfiber, polyester fabric that can move sweat away from the body and to the fabric surface, where it evaporates. Nike employs this technology in the design of a variety of products, including shirts, socks, pants, shorts, sweatshirts, sleeves, hats, and gloves. Since the technology platform has already demonstrated its usefulness in the marketplace, it is simpler to develop new products than if the technology had to developed from scratch.

Innovation is defined as “an idea, service or practice that is perceived as new by individuals or by a society” (Rogers, 1962), and as “The whole activity from invention (the discovery of a new device, product, process or system) to the point of first commercial or social use” (Walsh et al., 1993, p. 16). Innovation therefore involves the development of a novel idea, its exploitation as a market opportunity, and its potential to add value to a society. Innovations can be the results of an invention or of new product development and design activities.

Innovations can also occur at different levels, such as product, service, or process. Process innovation is about finding a novel way of achieving an output. In process innovation, the final product does not change, but the techniques or equipment for creating the product is improved. Although process innovation is less known compared to product and service innovations, it has greater impact on society. The introduction of automation in manufacturing, for example, enabled products to be produced faster and cheaper. Service innovation involves “changes in the process of delivering existing services or the development of completely new services” (Rothkopf, 2009). Stitch Fix, an online styling and retailing service offering personal styling services, is a good example of service innovation. An alternative to traditional retailing, the company sends kits with clothing and accessories from different brands hand-selected for a user’s size, style, and price range. Process innovation is also seen in the company’s technology, which uses AI algorithms and human stylists working in combination to make recommendations to clients for clothing, shoes, and accessories. Finally, product innovation is the introduction of a good that is new or significantly improved with respect to its characteristics or intended uses. Product innovation is closely related to product design.

The Innovation Spectrum

In The Four Lenses of Innovation: A Power Tool for Creative Thinking, Gibson (2015) discusses innovations from the perspective of “the pattern recognition principle,” defining trends as patterns of change and innovators as creatives who can recognize these patterns. Gibson introduces the concept of patterns with an term from cognitive psychology called automaticity, which help us form habits that, through repetition and practice, become automatic and reflexive response patterns requiring lesser brain activity (e.g., being able to talk to another person while driving). Collective patterns or trends can also be formed in societies, with, for example, large numbers of people watching the same TV shows, following the same clothing fashions, or using the same social media applications, and making subconscious choices based on what other are saying or doing. Some innovations alter these existing societal patterns or trends, while others introduce products, services, or processes that entirely disrupt existing patterns and form new trends.

Innovation is a buzzword that means different things to different people. There have been many attempts to classify innovation into dichotomous scales relating existing societal patterns. Abernathy and Utterback (1978) differentiated incremental and radical innovation, while Porter (1986) similarly illustrated continuous and discontinuous technological changes. Authors have also defined incremental vs. breakthrough innovations (Tushman & Anderson, 1986), and conservative vs. radical innovations (Abernathy & Clark, 1985), and efficiency, sustaining, and disruptive innovations (Bower & Christensen, 1995). If we were to think of innovation on a spectrum based on the degree of the novelty, on the most conservative end of the spectrum are the incremental innovations, followed by radical innovations, and finally disruptive innovations.

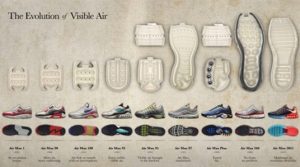

Incremental innovations involve modest changes to existing patterns over time, such as new product features and service improvements. These are enhancements that keep a business competitive—simply the next version of an existing product or a service perpetuating its existing performance. New versions of Nike Air Max shoes, with improved technical characteristics and minor changes in appearance, are a good example of incremental innovations. These shoes are characterized by pressured air pouches in the midsole that create cushioning and impact protection during the gait cycle. The pouches, visible from the exterior of the shoe, have taken many different forms and sizes over time, with improvements made for different purposes. This cushioning system then evolved into another product called Nike Joyride, featuring midsole pouches filled with colorful beads instead of air for improved and softer cushioning.

Proceeding along the spectrum, radical innovations represent a significant change in patterns, with distinct novelty in a product, technology, service, or business model compared to existing solutions. Radical innovation takes a current process or product and provides a significantly greater efficiency or superior technology. The first Nike Air Max, introduced in the 1980s, was a radical innovation, introducing the idea of using pressurized air for cushioning in a sneaker sole. Later versions of the Nike Air Max were based on this first radical innovation. As a radical innovation, Nike Air Max added a significant level of novelty to sneakers, but it did not make existing sneakers or shoes obsolete, disrupting related social and business patterns.

At the most radical edge of the spectrum are the disruptive innovations — ideas that disrupt societal patterns, entirely change an industry or a marketplace, and force competitors to adjust their view of the business. Disruptive innovations are cannibalize existing products or markets, or radically change a market or industry. For example, the invention of Nylon, the first commercial synthetic fiber, not only created a fashion revolution but impacted the course of history during World War II. The fiber was used to manufacture ropes and parachutes, which allowed the U.S. to be better equipped. And as skirt hemlines, nylon stockings became a coveted product, with thousands of women lining up to compete for the limited supply. The nylon stockings’ elasticity, light weight, strength, and ease of care made silk stockings, which did not stretch and required a garter belt, obsolete. In addition, the sheer nylon stockings created new behavioral patterns such as removing leg hair—still a mainstream trend, and one which has led to many other related products and services.

Another potential disruptive innovation which can completely change the way clothing is designed, produced, and retailed is 3D printing. Fashion designer Iris Van Herpen and several start-up companies have been experimenting with 3D printed clothing, which could create a completely new user experience in which users can download and print the latest designs in their homes. 3D printing also has the potential of making mass production obsolete, creating a new reality of on-demand, totally customizable clothing.

Trend Challenge

Discuss what innovation spectrum category the following product examples could fit. What characteristics make them to fit into one of these categories?

(Image retrieved from: https://www.sony.com/en/brand/stories/en/our/products_services/signature-series/)

Innovation and Trends

We live in a time of constant change. As a result, what individuals expect from products, services, and brands also changes. Trend research is about seeing these changes happen and evolving strategies to fit or even stay ahead of them. Trends manifest themselves at multiple levels from economic, social, political, and cultural contexts and through innovations. The stronger the trend, the more that related innovations will proliferate across different and sometimes unrelated industries. It is thus possible to define a trend as a change that is reflected in innovations. Detecting and filtering emerging trends and turning them into innovation opportunities can have a dramatic impact on an organization. Recognizing shifting trends and emerging hot-spots is critical to channeling innovation efforts to maximum effect. By dissecting a trend to its core components—adopters, location, timeframe, and drivers—you can begin to identify innovation opportunities.

The relationship between innovation and trend is chicken-an-egg; it’s difficult to identify which of the two exists first. While trends lead innovations, innovations can also start new trends. Especially disruptive innovations can transform current behaviors and create new ones, kickstarting new trends. Innovations stemming from new technologies which create completely new products or experiences and make existing alternatives obsolete can create new trends. The wide accessibility of mobile internet technology, for instance, has led to an on-the-go lifestyle trend in which all aspects of life, from work to personal, are intertwined and managed from mobile devices and, lately, wearable technologies and smart clothing.

Scientific and technological advancement can be a significant source of innovation. While technology-push creates new fields of opportunities for innovations, it requires user demand in order for people to feel motivated to change their existing patterns. Another important source of innovation is unmet latent user needs and wants, which can be traced by investigating changing trends and patterns in lifestyles.

Most often, innovations arise from the interplay of technology-push and market-pull, embedded in trends that manifest themselves in changing patterns. Recognizing the future potential of emerging trends opens up opportunities for new innovations. Researching trends requires in-depth study of changing patterns and shifts in people’s needs and wants. These trend insights, developed through in-depth research.

Trend Challenge

References

Abernathy, W. J., & Utterback, J. M. (1978). Patterns of industrial innovation. Technology review, 80(7), 40–47.

Abernathy, W. J., & Clark, K. B. (1985). Innovation: Mapping the winds of creative destruction. Research policy, 14(1), 3–22.

Bower, J. L., & Christensen, C. M. (1995). Disruptive technologies: Catching the wave.

Gibson, R. (2015). The four lenses of innovation: A power tool for creative thinking. John Wiley & Sons.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). Preface to motivation theory. Psychosomatic Medicine.

Maximilian Rothkopf. (2009). Innovation in commoditized service industries: An empirical case study analysis in the passenger airline industry (Vol. 2). LIT Verlag Münster.

Mason, H., Mattin, D., Luthy, M., & Dumitrescu, D. (2015). Trend-driven innovation: Beat accelerating customer expectations. John Wiley & Sons.

Porter, M. E. (1986). Changing patterns of international competition. California Management Review, 28(2), 9–40.

Tushman, M. L., & Anderson, P. (1986). Technological discontinuities and organizational environments. Administrative Science Quarterly, 439–465.

Walsh, V., Roy, R., Bruce, M., & Potter, S. (1993). Perspectives on design and innovation. Creativity and Innovation Management, 2(2), 78–86.