Chapter 6 – Trend Lifecycles and Adopter Categories

Gozde Goncu Berk

Future trends manifest themselves in the behaviors, needs, and wants of today’s niche user, and in novel product, service, and process innovations that break existing patterns. To identify a trend at its emergence, it is vital to detect these pattern changes early, and to differentiate a trend’s lifecycle stages. Just as trend forecasting requires systematic research and analysis, and is not a sudden spark of insight, trends themselves do not appear out of the blue. Trends diffuse within a society over time based on their own characteristics and those of the people who adopt the products, ideas, and services that represent those trends.

Trends do not take place in a vacuum; they are embedded in the context. A trend forecaster needs to know where to look for signs to capture an emerging trend in its infancy. Trends are driven by large forces, and manifest themselves through certain types of behaviors, new styles, products, or services. As noted earlier, for example, it is expected that population aging will be a central megatrend of the future, driven by falling fertility rates and increased life expectancy. A trend forecaster trying to discover specific trends that fall under this umbrella megatrend might narrow their scope to places like Japan, with its large aging population, to track down innovators and early adopters of functional, personalized, or individualized products and services for older individuals. On the other hand, policies related to healthcare, infrastructure, housing, culture, and family dynamics all affect the lifestyle and trend adoption rate of aging baby boomers.

Trend forecasters use their understanding of the trend adoption and trend lifecycle processes to narrow down and target research efforts with a structured plan for where and how to look for early signs of new trends. The “Diffusion of Innovations” theory, developed by Everett Rogers in 1962, addresses how and why new ideas diffuse and get adopted in a society. While originating in communications studies, the theory is often used in other fields, including fashion and design, to understand the spread of trends.

Trend Adoption Process

As discussed earlier, trends encompass many emerging user behaviors, needs and wants, and novel products and services. Faith Popcorn, for example, describes a trend she calls “Eve-volution,” referring to the rise of women in the culture and their impact on businesses. Many products and services that relate to women cluster around the Eve-volution trend. SuperShe Island, for instance, is a female-owned, private island resort exclusively for women that offers motivational talks and activities such as yoga and meditation (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SuperShe_Island). We’ll use the term trend adoption to refer to adoption of products, services, or user behaviors clustered under a specific trend.

According to Rogers (2003), an individual’s decision to adopt something new is a process that occurs over time, in five stages: 1) knowledge, 2) persuasion, 3) decision, 4) implementation, and 5) confirmation. Knowledge occurs when a potential adopter learns about the existence of the new idea and becomes aware of how to use it. With persuasion, the individual forms a positive or negative opinion towards the new idea based on its perceived attributes, such as its advantages; its compatibility with the individual’s needs and wants; its level of complexity, trialability, and observability; and information gained from the evaluation by peers. Decision happens when the individual makes a choice to adopt or reject the idea based on the persuasion stage. In implementation, the new idea is put into use until it loses its distinctive characteristics and is no longer identified as new. Confirmation happens when reinforcement is needed about a decision to adopt or reject the new idea after implementation. How early or late an individual goes through this adoption process, as well as its speed, are related to the individual’s personal characteristics and to attributes of the new trend.

Other authors have adopted similar models to describe how trends are adopted within the fashion field. Kim et al. (2011) introduced a five-step fashion trend adoption process, including 1) awareness, 2), interest, 3) evaluation, 4), trial, and 5) adoption. With awareness, an individual becomes aware of a trend for the first time. Interest is the process of gathering more information about the trend based on piqued curiosity. In the trial stage, the user tries and tests the new trend to see if it meets their expectations. Finally, in the adoption stage, the user fully adopts the trend. In contrast to Roger’s model, the trend adoption model does not include the post-adoption stages that can illustrate the point in time at which the new trend begins to wind down.

| Innovation Adoption (Rogers,2 003) | Trend Adoption (Kim et. al., 2011) |

| Knowledge | Awareness |

| Interest | |

| Persuasion | Evaluation |

| Trial | |

| Decision | Adoption |

| Implementation | |

| Confirmation |

Table 1: Models that compare stages of innovation and fashion trend adoption as depicted in the literature.

Other authors define fashion trends as cyclical patterns that reoccur over time. According to Easey (2009), the fashion cycle starts with the introduction of a new style, continues with growth—where the style spreads in a population, gains popularity, reaches maturity, and is accepted as a major trend—and then loses popularity in the decline phase. Rousso (2012) defines the fashion trends cycle in five stages: introduction, rise, culmination, decline, and obsolescence. The fifth stage, obsolescence, refers to the end of the fashion cycle for a trend.

Trend Challenge

Think about a new product, service, or lifestyle change you recently adopted or tried and rejected. Consider the following questions, and note your answers in 1–2 paragraphs for each question:

- How did you first learn about it? (It could happen simultaneously through multiple channels)

- What sparked your interest or persuaded you to try it?

- How did you evaluate whether it fits your expectations?

- When and how did you fully adopt or reject it?

- If you adopted the product, service, or lifestyle change, how would you define its novelty and how well it currently meets your expectations?

Rogers (2003) also describes five perceived attributes that influence rate of adoption of a new product or service:

Relative advantage is the perception of the improved benefit of adopting a new product, service, or trend in comparison to the one it supersedes. The greater a new trend’s relative advantage, the faster its adoption. A smart watch is an example of a product associated with the health consciousness megatrend. The relative advantage it offers compared to a traditional watch is improved wellbeing and health through real-time monitoring of vital signs such as heart rate, sleep, or calories burned.

Compatibility refers to how a new product or service fits with the experiences, needs, values, and existing habits or products of an individual. If the new idea is compatible with these factors, its rate of adoption is much faster. A new smart watch, for instance, will be adopted fairly quickly by a person who owns a smart phone and has experience with the operating system, and less quickly by someone with no experience using a smart communication device. Individuals who need to track their health or athletic performance will also be more likely to adopt a smart watch.

Complexity is the degree to which a new product is perceived as difficult to understand and use. Unlike relative advantage and compatibility, complexity is negatively correlated with the rate of adoption. The more a new idea is easy to understand and implement, or a product is intuitive and easy to use, the faster is its adoption. Compared to a traditional watch, a smart watch is harder to operate and maintain; it requires navigating a user interface, synchronizing the watch with other devices, and charging its battery. On the other hand, a smart watch with an intuitive user interface or one compatible with the operating system of an already-owned smart phone is likely to be adopted more quickly than a more complicated or entirely new one.

Trialability is the ease of testing a new trend before a potential adopter adopts and implements it. Being able to try out the new idea reduces the risk for adopters and increases the rate of adoption. Marketers use trialability to increase the adoption of a new product. Smart watch retailers, for example, offer possibilities of interaction by displaying the watches in user-friendly retail settings and organizing try-on appointments and demonstrations.

Observability is how visible the product is to others. New products that are used publicly, like a smart watch, spread much faster than products used in private. Social media has been a highly effective tool for increasing the observability of new ideas. Marketers utilize popular social media accounts to increase the observability of their new offerings.

The speed at which a trend adoption process takes place, and whether a new product is adopted or rejected, are influenced by these five attributes. While the relative advantage and compatibility of fashion products such as clothing and accessories may be less obvious, product trends have very high observability and trialability and low complexity. A fashion trend in 2021, for example, was pairing chunky boots with dresses, skirts, and ankle-length trousers. The relative advantage of following the trend was being able to identify with the latest fashions and to showcase a fashionable identity; most users likely had prior experience wearing boots and and the trend was compatible with the need for comfortable footwear; trying this trend is not a complex task and anyone can do so at a store before making a purchase; and the observability of the trend was very high publicly as well as in online realms.

Trend Challenge

Think back to the product, service, or lifestyle change you analyzed in the previous trend challenge activity, and write 1-2 paragraphs in answer to each of the following questions:

- What were the main relative advantages it provided?

- How would you evaluate its compatibility with your previous experiences, needs, and values and your other existing habits?

- How would you discuss its complexity? How easy is it to use or understand?

- How would you rate its trialability and why?

- How observable was the trend? How did you learn about it?

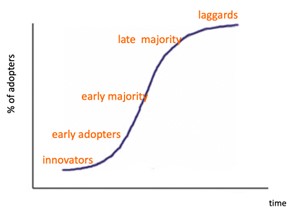

Adopter Categories

New ideas are not accepted all at once. Some people are more apt to try the new trends at their emergence, while others need more time or don’t ever adopt. This process of adoption, or the diffusion of the new idea in a society, takes place over time following an S-shaped curve (Figure 1). Only a few individuals initially adopt the new trend, but over time and if it becomes popular, more and more individuals adopt it and the adoption rate increases (Goncu-Berk, 2015).

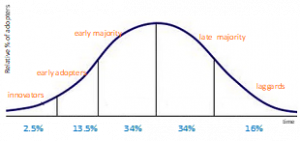

Rogers (2003) introduced “adopter categories” based on the pace at which individuals react to something new, such as using or purchasing a new product. The distribution of the percentage of adopters over time forms a bell-shaped curve (Figure 2), divided into the five adopter categories of (1) innovators, (2) early adopters, (3) early majority, (4) late majority, and (5) laggards, based on the degree to which an individual is relatively early in adopting new ideas compared to other members within a system. Another way to examine adoption over time is the relative percentage of adopters of a new trend. In this case, 2.5% of the population are innovators, 13.5% early adopters, 34% early majority, 34% later majority, and 16% laggards.

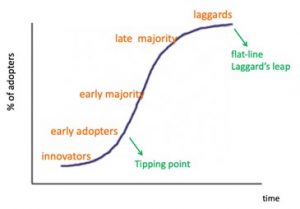

In the adoption process, the tipping point refers to the critical mass or threshold at which an emerging trend becomes widespread and highly visible (Figure 3); it’s the sweet spot of diffusion from early adopters to early majority. Trend researchers and forecasters study innovators and early adopters to discover an emerging trend and evaluate whether it will become mainstream—whether it will pass the tipping point. Trend forecasters are also interested in what is called the flat line or the laggard’s leap, the point at which the trend is no longer novel and is at the end of its lifecycle (Figure 3).

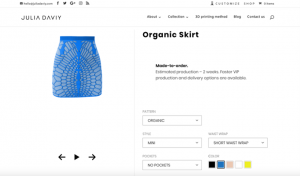

Innovators are the first group of people a trend forecaster needs to track to detect a trend in its infancy. A recent innovation related to clothing and textiles is the application of 3D printing technology for the design and manufacture of garments. Several new ventures retail 3D printed clothing, and haute couture designers are experimenting with the technology. Julia Daviy (juliadaviy.com), for example, offers made-to-order 3D printed items such as the mini skirt. Innovators who would be first to adopt a skirt like this would need to be knowledgeable about 3D printing technology and its application in the fashion industry in order to seek out such a product, and would also need the financial means to acquire it.

Early adopters follow innovators’ implementation and adoption of the new idea. They operate as opinion leaders in the diffusion process, and other potential adopters look to early adopters for information and advice about the new trend. Early adopters are highly interconnected and visible; their opinion leadership can therefore influence the mass opinion. Early adopters have a critical role in triggering what is known as the “critical mass”—the point at which adoption of a new idea by enough early adopters leads to adoption by a much larger number. Trend forecasters study early adopters to understand the spread and impact of a trend, since they mark the tipping point from a minor trend to a major, highly visible, and influential one (Raymond, 2010). Especially with the spread of social media, the sharing of pictures, videos, or recommendations by early adopters with many followers is a highly effective way of influencing the opinion of the masses.

Early majority and late majority adopters are two subsequent groups which make up 68% of the population that adopts an innovation, and represent individuals who are more deliberate and skeptical in their decisions (Goncu-Berk, 2015). Early majority adopters are also socially active, but they are not opinion leaders. They are deliberate in adopting a new trend and stick with it the longest, while late majority adopters are the quickest to drop a trend. Trend forecasters track early majority adopters to assess profitability of a trend, and later majority adopters to understand when a trend is at a downturn (Raymond, 2010).

Laggards are the last, slowest, and most resistant to adopt new ideas in Roger’s Diffusion of Innovations model (2003). They are defined as the most traditional and reluctant to change. Trend forecasters track this group to verify that a trend has reached its limits and that new related ideas are already emerging and diffusing in the first adopter categories. The point at which a trend reaches the laggard is defined as the “laggard’s leap” or “the flat line,” denoting no potential increase in the number of adopters after this stage.

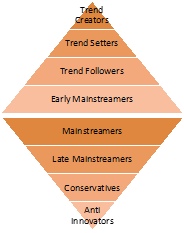

Vejlgaard (2008) defines adopter categories in a similar way, using the “Diamond Shape Trend Model.” This model includes eight adopter categories, with the widest, middle section representing most of the population, and the two narrow ends the adopter categories with the smallest number individuals. Trend adoption travels from one adopter category to the next, from the top to the bottom. In this model, the more visible and observable a trend is, the faster it flows. For example, it takes one to two years for cosmetic trends to travel from trend setters to mainstreamers, two to three years for clothing and accessories, and five to seven years for interior design. The speed of the diffusion is highly dependent on contextual factors such as geographic location, political environment, and socio-cultural and religious values of the population.

At the top of Vejlgaard’s trend adoption model are trend creators, who represent a small group of risk-taking inventors, designers, or entrepreneurs who create and launch the new ideas. Trend setters, the first to accept and try a new product, are usually young, wealthy, and style-conscious individuals, celebrities, or social media users. They are influential in promoting the new idea or the trend, and in making it visible to the trend followers, who need the assurance of others in accepting the new. Early mainstreamers mark the diffusion of the trend to the majority, while mainstreamers adopt a new trend when everybody else has done so. Late mainstreamers adopt the trend a few seasons later, and conservatives prefer to stick with fewer older styles. Finally, anti-innovators refuse any new change or trend.

Trend Challenge

- Write a paragraph discussing similarities and differences between Roger’s and Vejlgaard’s adoption categories and how they relate to one another.

- Browse through trendhunter.com and identify a trend you are interested in. Write a paragraph briefly defining the trend, and discussing who would be the innovators and early adopters of that specific trend. What are their likely demographic characteristics?

Fashion Adoption Process

Fashion is one of the most visible expressions of trends, reflecting changes in the collective aesthetic and behavior through multiple mediums. In this book we define fashion not only as clothing and accessories, but as personal expression and a channel for identity. Fashion adoption decisions can be made based on factors other than a product’s functional and practical relative advantage. Individuals don’t adopt high heels, for instance, because they offer a better walking experience; they do so because they like the message the shoes convey—of being up-to-date or in fashion.

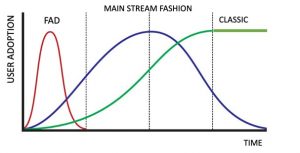

Fashion products can become a fad or a classic, depending on the duration of their effect. “Fad” and “classic” are often used in fashion-forecasting literature (Figure 6). A fad is a short-paced, popular collective behavior that fades rapidly once its initial novelty is gone. Recent fads include videogames, the Ice Bucket Challenge (raising awareness for ALS), or posting pictures of what a person might look like as they age. Small sunglasses, transparent accessories, and the hipster beard are fashion-related fads that did not have long life spans. Fads are easily recognized and adopted as short-term ephemeral trends. A classic, on the other hand, is a more durable product with a longer lifespan and a lasting significance. Leather jackets, the little black dress, Hunter rainboots, and Duluth Pack bags are examples of classic fashion products. Classics are often priced higher than fads, but not always.

Trend Challenge

Write a paragraph describing a fad and a classic product. Discuss the features of each, their adoption timeframe, and who their adopters might be.

How and why fashions change has been studied by many in various disciplines over the years. Related theories each depend upon a recognizable change in direction of the trend, and change is depicted in various ways such as the attributes of a look, the origin of the style, and its distribution and adoption.

Pendulum Swing: Pendulum swing theory defines fashion trends as periodic movement between two opposite points of exaggeration in a style. These swings may occur over decades, or over a fashion season. When a trend can no longer proceed in one direction, it starts moving the other way. Such swings are defined and delimited as they relate to the body. When the heel height of a shoe is extreme, for example, it can become a stilt.

Brannon (2010) suggests that an idealized version of the pendulum would pause at a compromise point and then swing in the opposite direction. Once waistlines reach a level where they cannot go any higher, for instance, it would be expected that they would lower quickly to call attention to the change. When the fit of close-to-the-body leggings is extreme, the opposite movement would be toward wide-legged trousers as another extreme, before possibly settling somewhere in the middle as a less extreme and accepted fashion.

Trickle Down: The oldest theory of fashion distribution is described by Veblen (1899), an economist. In this theory, a social class is distinguished based on conspicuous consumption and leisure. Fashion originates within the upper social class and trickles down to the lower classes through imitation, as the upper class recreates new forms of fashion to affirm their status in the society. Similarly, Simmel (1904) defines fashion change from the perspective of social distinction and integration, with the lower class trying to obtain the status of the elite by imitating their fashion, and the upper class subsequently creating new innovations and obsolescence to maintain the demarcation. While the trickle-down theory can be related to the flow of some trends from haute couture to fast fashion or from celebrities to the majority, the flow of trends based on social hierarchy may no longer be as relevant as it once was. With the advent and rapid spread of social media, anyone can create trend-related content and influence others.

Trickle Across: The trickle-across theory claims that new styles diffuse horizontally among similar social groups and communities within a short timeframe (King, 1963; Robinson, 1975; Blumer, 1969). New styles emerge from a process of collective selection, in which collective tastes are formed by many people. Collective taste functions as a selector for the acceptance or rejection of ideas, and as a formative agent for innovation. In the 21st century, mass production combined with mass communication makes new styles available simultaneously to all socioeconomic classes. Again, social media may become influential in defining groups who adhere to certain styles and, through their promotion and acceptance, define those styles as fashionable.

Trickle Up: A relatively newest theory of fashion flow by Field (1970) suggests that new styles emerge from the street, a subculture, or lower-status groups, and are then adopted by higher-status groups or the mainstream. Sproles’ (1979) subculture leadership theory also defines fashion trends in an upward direction from subcultures to the mainstream. Styles that emerge from lower socioeconomic groups are usually generated by adolescents and young adults who belong to subcultures. Age replaces social status as the variable that conveys prestige to the fashion innovator. Punk fashion, for example, with roots in the British youth subculture, has been disseminated and commercialized by designers, led by Vivienne Westwood, a prominent London designer of the 20th century. Today, fashion companies and trend-spotters pay close attention to street styles to detect emerging trends that have potential for mainstream acceptance.

Trend Challenge

References

Blumer H. Fashion: (1960). From class differentiation to collective selection. The Sociological Quarterly 10(3):275–291.

Easey M., ed. (2009). Fashion marketing. John Wiley & Sons.

Field A. (1970). The status float phenomenon: The upward diffusion of innovation”.” Business Horizons 13, 45–52.

Goncu-Berk, G. (2015). Fashion Trends. In Bibliographical Guides. London: Bloomsbury Academic. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/9781474280655-BIBART12001-ED

King C. (1963). Fashion adoption: A rebuttal to the “Trickle Down” theory.” In Toward Scientific Marketing, edited by S. Greyser. American Marketing Association.

Kim, E., Fiore, A. M., & Kim, H. (2013). Fashion trends: analysis and forecasting. Berg.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological review, 50(4), 370.

Mason, H., Mattin, D., Luthy, M., & Dumitrescu, D. (2015). Trend-driven innovation: Beat accelerating customer expectations. John Wiley & Sons.

Raymond M. (2010). The trend forecaster’s handbook. Laurence King Pub.

Robinson E. (1975). Style changes—Cyclical, inexorable, and foreseeable. Harvard Business Review 53(6): 121–131.

Rogers E.M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations. 5th Ed. The Free Press.

Rousso C. (2012). Fashion forward: A guide to fashion forecasting. Fairchild Books.

Simmel G. (1904). Fashion. International Quarterly 10: 130–155.

Sproles B. (1979). Fashion: Consumer behavior toward dress. Burgess.

Veblen T. (1899). The theory of the leisure class. Macmillan.

Vejlgaard, H. (2008). Anatomy of a trend. McGraw-Hill