Chapter 3 – Developing a Collective Perspective

Marilyn Revell DeLong

A collective perspective is needed to understand how trends work within the marketplace. To capture the trend outlook involves becoming aware not only of one’s personal aesthetic response and how one’s likes and dislikes influence selections, but of the perspective of the user groups involved in a trend who may have different needs and desires. Understanding one’s personal response is the first step in learning about trends. The next step is to develop a collective perspective that involves the user and the context of the time and place in which the trend is occurring.

The times in which we live change continuously. In this regard, the zeitgeist, a German term meaning “spirit of the time,” is prevalent in thinking about trends. As a forecaster, you’ll need to recognize what is considered an expression of the current time—what is perceived as new, up-to-date, and modern and attractive for yourself and other individuals. But this is not easy.

The times in which we live change continuously. In this regard, the zeitgeist, a German term meaning “spirit of the time,” is prevalent in thinking about trends. As a forecaster, you’ll need to recognize what is considered an expression of the current time—what is perceived as new, up-to-date, and modern and attractive for yourself and other individuals. But this is not easy.

Though living at a particular time and in a particular place, an individual is often not fully aware of the shifts in societal directions that are trending as harbingers of change. It takes practice, and a large measure of curiosity and intuition, to become aware of this zeitgeist. To describe this zeitgeist, you need to be able to distinguish individual, collective, and universal perspectives.

Individual, Collective, and Universal Perspectives

Fashion is influenced by how we choose to design our individual appearances. But what an individual wears and how they choose to appear is ever changing because of the zeitgeist of the time. Today you may be wearing a particular ensemble with a particular scarf or tie to set it off; tomorrow, wearing the ensemble minus the scarf or tie but with the addition of a jacket and brightly colored shoes. The zeitgeist reflects the current mood and affects changes in what individuals consider up-to-date. This includes the products we select, the way we use them in combination, and when and how we discard what is perceived as out-of-date.

Individual selections can influence the spirit of the times and fashion. It is important to consider the individual who plays an active role in selecting product innovations: some people are influential in the way they accept products to attract special attention because they like to be first to appear in or own the latest products. As such, they influence others because of their quick adoption of an innovation. Such individuals may be like chameleons, changing from one product to another. By contrast, others may have settled upon their own individual style; they are comfortable with a product or wearing the same style that varies little from year to year. They may not be a great influence on others, and may be oblivious to product innovations offered in the marketplace. We will learn more about these variations in how individuals directly or indirectly reference the collective experience that is fashion.

To be fashionable means recognizing the relation of your individual response to the collective response of the group or groups with which you currently associate. Relating significantly to a time and being able to say that something is “so current” or “so retro” illustrates reference to a collective response within a given societal group—or multiple reference groups, i.e., the people you work with, the group you exercise with, those who live in your city. Fashion becomes a back-and-forth negotiation that occurs between wearing what provides an individual identity and what still conforms to a collective audience.

This collective response was noted by Blumer (1969) in his early research on collective selection. Members of the apparel industry selecting for a target market from current designer collections gave evidence of the spirit of the times in making their selections. Though their target markets differed, their selections were surprisingly similar and mirrored the zeitgeist. Selecting wisely meant both recognizing the zeitgeist and understanding what would be accepted as a current look among individuals in their specific target market. Both the zeitgeist of the collective and the wants, needs, and desires of the individual were therefore recognized in their selections.

Realizing that fashion is about both an individual’s identity and their conformity within a group, how do you assess the cohesiveness of a collective? A target market identified by age, lifestyle, or other demographics may be marked by specialized characteristics. Such a group may become a style tribe—a group within a culture whose members wear a recognizable and distinctive look. Ted Polhemus (1994), the anthropologist who coined the term, pointed out the need for individuals within a group to dress and appear alike. This collective response is a congregating force of style tribes. Sometimes the tribe is named because the identifying characteristics are so distinctive they gain recognition as a group different from the wider collective. The use of the term recognizes the decentralizing nature of fashion today. We select products based upon the zeitgeist, but also upon factors such as lifestyle and demographics (e.g., age and gender).

To observe and describe the zeitgeist involves cultural brailing—gaining an awareness of what is happening around you and then assessing its meaning. A first step is becoming aware of how others within your group look and act like a collective that is distinguishable from other groups. An individual’s aesthetic response is not formed in a vacuum independent of others. To assess a trend, a person must be aware of similarities as well as differences among members of associated groups. This includes not only features of how we dress, but motivating needs and wants. A collective need based on function and comfort, for example, may be expressed in a number of ways that relate to the zeitgeist—the way we appear, but also, simultaneously, the cars we drive, the furniture we use, the houses we live in, and the type of entertainment we enjoy. All are part of the zeitgeist!

A universal perspective arises when many people across groups and cultures agree upon and adopt a similar innovation or style. Many factors of a global dimension can arise to increase such a universal response. Traveling, for example, makes a person consider the types of clothing that might be acceptable to wear when visiting another country and culture. An example of a universal perspective might be a casual look involving blue jeans, a T-shirt, and a mobile phone. Even though these products reflect the zeitgeist of the West, they have become products of a universal response that function around the world as an expression of fitting in, of being recognized and accepted. As products are designed and manufactured globally, the market for them may be increasingly distributed and accepted worldwide.

The rise of global communication via the Internet has created the potential for an increase in universal responses that span a variety of cultures. The widespread influence of social media is a factor in this spread, and the global reach includes acceptance of distinguishable styles by subcultural groups. The “Emo” style of 2020, for example, has been influenced by style icon Billie Eilish and adopted mostly by younger age groups with some style characteristics of punk, such as heavy use of black and metal, wearing Converse shoes or combat boots, styling dyed hair with a side part and swept over one eye, and wearing dark eye liner and lipstick. Another example is “Anime,” a style of Japanese animation, often with adaptations of comic characters with large and emotive eyes. Anime has spread beyond the culture of Japan where it originated, and has become an aesthetic response recognized as it distinguishes a subcultural group that has evolved into a universal perspective.

Reflecting upon your aesthetic response and sorting out what is individual, collective, and universal is useful in trend forecasting. Your ability to forecast change may depend upon whether you are looking to satisfy only your individual aesthetic response, the collective nature of a specific group, or a more global perspective.

Trend Challenge

Look over a current fashion magazine. Identify and paste into your notebook three products you’re unfamiliar with. Use bullet points to describe them. Looking at the three together, what similarities do they share? How can you describe those similarities in terms of style trends? You might, for example, notice a new lipstick that features a shiny gold case and a bright, bold, and shiny-wet look. Or perhaps a natural look is trending in shades of nude, with matte textures. Look for similarities in the three products and translate those similarities to trends. Be sure to name the style. It okay to use the name the company has assigned to it.

Fashion and Style in Trends

Fashion involves both order and the change occurring in a society where social movement is possible. According to Entwistle (2001), fashion in one’s dressing is a specific system for the production and organization of dress grounded both in time and location: “it is a system of dress found in societies where social mobility is possible, . . . and it is characterized by a logic of regular and systematic change” (p. 41). Kaiser (2013) confirms its collective as well as its evolving nature:

…fashion involves becoming collectively with others. Fashion materializes as bodies move through time and space. Time and space are both abstract objects and contexts: the process of deciphering and expressing a sense of whom we are (becoming) happens in tandem with deciphering and expressing when and where we are. (p. 1)

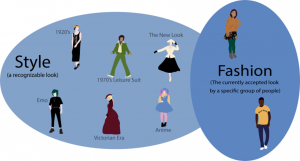

While related, fashion and style are not synonymous in meaning. In aesthetics, style is the distinctive pattern and characteristic expression that defines a product or an art form (Nystrom 1928, p. 3). Style is about those characteristics that define one product or combination of products, but style does not necessarily reflect acceptability or currency. It can thus be recognized as new, but also as historic or recently outdated. An individual may choose to dress according to an individual style, but not necessarily be in fashion. Fashion, in contrast, is defined as the prevailing style, with an emphasis on an accepted and recognizable pattern of expression. Fashion involves the zeitgeist, the expression of what is recognized and accepted as current and up-to-date at a particular time and place and as defined by a specific group of people.

Fashion in Appearance

Fashion related to appearance is the way a group of people at a given time and cultural setting choose to look. Fashion in clothing, defined as the currently accepted style in the appearances of a group of people, evolves and changes with time and cultural values. Being fashionable is thus about appearing current and up-to-date, which often means focusing on a myriad of details such as how clothing fits and moves with the body, how it is proportioned, and how it combines colors, textures, lines, and shapes into currently accepted product designs.

Being in fashion involves a balance between expressing one’s individuality on one level and conforming to a group on the other. This tension and balancing act may be understood as a continuum between individuality and conformity. Today we label generations for when they were born and what happened historically to influence their cultural identity (e.g., the baby boomers, born 1946–64; Gen Z, born 1997–2012). In DeLong, et al.’s study (2018) comparing two generations in the same locality, the older females matured during a time when coordinated ensembles were popular, with clear divisions between formal and informal occasions. Conversely, the younger females grew up within a culture where boundaries between types of occasions were blurred.

The motives underlying how we appear can change during our lifetime. For example, in a study of baby boomers, they were asked how the motives underlying their choices of appearance had changed since high school. They responded that in high school they were more concerned with dressing individually, but were now more interested in dressing to conform with their group. They agreed that the desire to dress to express their individuality had waned. As they are now retiring, they wanted to appear a bit more like their friends.

Today there are a multiplicity of fashion sources that depend upon style tribes—groups that identify with each other by conforming in their appearance. These include punk, goth, and the Red Hat Ladies. Such groups have become important in creating the zeitgeist. And increasingly, this multiplicity of what we know as fashion is evident in social media, where people are free to explore many sources of style and fashion.

Our concept of fashion is formed from our instantaneous perceptual response to what we see, such as “I like it.” This judgement may be an unconscious part of our experience, as described by Norman’s three levels of visceral, behavioral, and reflective (2004). We rush to judgement (Level l) rather than ponder the reasons for our judgement (Level 3). Then, if our judgements are confirmed repeatedly, they develop into recognition of a pattern and habits of thought and behavior (Level 2). We recognize a necktie, for example, through its shape and its placement on the body, and we often see it being worn with a white shirt. This is especially true for those who frequently see this combination, confirming it as part of the professional appearance of adult men in certain occupations. And because we recognize this pattern, it becomes a construct of certainty—a code. To recognize and understand a trend, the trend forecaster needs to make conscious this unconscious coding. We can only do this by internalizing and reflecting upon what is so familiar that we take it for granted. Becoming aware of what is familiar as pattern or code is the first step in recognizing a new pattern that deviates from the familiar.

The limits of design lie first in the imagination and second in our readiness to accept change (Loschak, 2009). So if we can become aware of the basic construct, we can then recognize a change in the pattern or code. High-end designers constantly push boundaries and expect that, if we are to appreciate their work, we will first recognize the familiar construct or code and then see what has changed—the deviation from what is familiar.

Martin Margiela, for example, is an innovative and futuristic designer of the Belgian Antwerp Six. He is recognized for always pushing the boundaries of our expectations about how clothing should look, so much so that he is sometimes referred to as a disruptive designer. From a rational perspective, we know that the body is symmetrical and that a jacket usually has two similar sleeves for the two arms. Margiela pushes the edges of that boundary, creating asymmetrical design that does not recognize or accommodate the two arms. Asymmetry as it is expected to relate to the symmetrical human form is reimagined. A trend forecaster recognizes and reflects upon this asymmetry as an abstraction that permeates the products we see and wear, even though it is modified to accommodate human movement.

Fashion is a non-linguistic sign system based upon such constructs and codes. We need to perceive and recognize how a sleeve is a sleeve and how it differs from a trouser leg. The specifics of clothing involve how parts combine and relate with the human body. For a design to be perceived as new requires that it differ from the basic code or construct. How would you respond to a sweater with five sleeves, for example? To perceive it as new, you would need to recognize the difference from the basic construct. To notice details that deviate from the familiar, you must first understand the familiar and not take it for granted; it must reach your awareness. Barthes (1990) describes fashion as a sign system that requires a language to communicate; fashion is a language that defines a collective imaginary.

Being fashionable in one’s appearance is about continually changing that appearance to reflect the zeitgeist. “Fashion” means a style that is both distinguishable and accepted by some group of people, which may be a subculture or mainstream group. You could, for example, refer to the fashion of teenagers at a specific school and the way they identify with each other to look similar in their style of dressing. Or you could refer to the pattern in dressing, the style, considered fashionable in the city where you live.

Trend Challenge

Style in Appearance

Styles are established and recognizable patterns of the overall expression created by one’s appearance, and involve categories and combinations of shapes, lines, colors, surfaces, and silhouettes that become recognizable because they are repeated or strongly related to a specific time, group of people, or location. A term like “1970s retro” is a reference to past fashion in clothing that is recognized as involving specific interrelationships of lines, shapes, surfaces, colors, and silhouettes. Streamline Moderne, a style that emerged in architecture and design in the 1930s, is characterized by rounded edges and horizontal “speed lines” inspired by aerodynamics. This style continues to be referenced because of these expressive interrelationships.

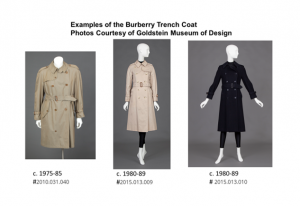

Sometimes a pattern of relationships within a product category becomes an enduring style—a recognizable pattern or image that may be reintroduced from time to time with minor variations. The trench coat is such an example. The coat’s design is memorable because of its smooth surfaces, tailored collar and lapels, front opening (often with a double row of buttons), belt, and khaki fabric. The trench coat flatters many body types for both men and women, and in the U.S. has been associated with detectives and private investigators. As a style, it has been worn throughout much of the 20th century, even though designers may change details to make it fashionable once again.

Styles can also be identified in terms of how they differ from other similar styles. In examining a blazer and suit jacket, for instance, we recognize the blazer as having a distinctive pattern of relationships—a tailored piece of outerwear fitted to the upper torso with long sleeves, a center front opening, tailored lapels and pockets, as well as other tailoring details. So far, the blazer could be considered synonymous with the style of the more formal suit jacket that accompanies a two-piece suit with matching trousers. But as fashion, the blazer is considered less formal and is defined as a casual accent by the way it is worn—often with blue jeans, T-shirt, or open-collared shirt. We recognize the style of the blazer as a distinctive pattern of features that provides a characteristic expressive effect in the wearing, one that is more casual than that of a suit jacket with matching trousers worn with a buttoned-up shirt and tie.

Be aware of the language used to describe a style. This includes the commonly understood language that traverses groups, as well as the nuanced language of those “in the know.” The term “style” is used in a variety of ways that shorthand its meaning. “This person has style,” for instance, means that the individual consistently looks and acts in a distinctive and characteristic manner. Here, the term is used primarily as a reference to details that may or may not be recognized by the receiver of this information. In another instance, “style” identifies an expressive pattern of shapes and surfaces as the basis to categorize and give meaning to what is viewed, even though the details are not provided. Examples might include “The style of this ensemble is defined by the 1940s,” referencing a group of characteristic and defining features of 1940s dress, or “The style of the designer portrays a soft and feminine look.” In these instances, the language is shorthand and does not provide the details needed to understand the meaning. In this case, the trend forecaster must find ways to more clearly describe and communicate a style.

Trend Challenge

Think of products whose terminology gives reference to several of its features, but is shorthand for the meaning and make it clear only for those “in the know.” For example, what is implied by the terms “blazer,” “onesie,” “crop top,” and “Bermuda shorts”? Is the term clear in communicating how the product looks? Is there room for confusion? What details may be needed to further describe the product itself, and describe how it would be used and by whom?

A single word may be used to communicate the complexity of details that make up a style or “look.” Such a look may be understood by those “in the know” about the details. A “Chanel” suit, for example, is named for the French designer of the early 20th century who dressed women in casual clothing that contrasted dramatically with previous styles. In the U.S., a Chanel suit probably references her comeback in 1954, when her signature look for women became a two-piece pencil skirt with a jacket, often with a geometric surface pattern such as checks, and with coordinating braid around the neckline and jacket front. The suit pictured includes three pieces, with jacket, skirt, and a coordinating blouse to be worn along with chunky costume jewelry—the signature Chanel suit style of 1955. (Photo courtesy of Goldstein Museum of Design Catalog #1986.034.001). Recognizing these details is necessary for understanding the references made to Chanel in 2021, in a comparison with the work of Virginie Viard, Chanel’s creative director.

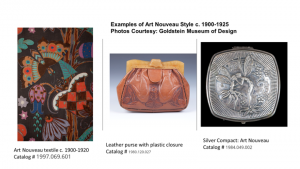

Style as an expressive effect can apply to a single category of product form or permeate several categories—e.g., clothing, painting, and interiors. Alessi, for example, is an Italian kitchenware company, recognized today by its playful design features embedded in functionality and its use of bold colors. Art Nouveau, on the other hand, is recognized across product categories as an art movement that flourished from about 1890–1910 throughout the U.S. and Europe and that is defined by a characteristic pattern of expression. It is defined by natural and organic shapes that result in elegant designs with long, sinuous, lines. The style was an attempt to modernize many forms of design, and it has been employed most often in architecture, interior design, jewelry and glass design, and illustration. The photos below, from the Goldstein Museum of Design, show design inspired by Art Nouveau. Art Nouveau is a consistent and recognizable style that references the early 20th century. As a past style its characteristics are still distinctive, but the style is not considered in fashion today.

Trend Challenge

In a previous Trend Challenge, we identified characteristic appearance choices among consumers and small groups that we encounter. Let’s take those elements into a broader context, working backwards to identify how those characteristics emerged. First, select a small group recognized for its characteristic style:

- Create a customer profile: What do they have in common? How old are they? Where do they work? What do they do for fun?

- Describe the style as clearly as you can. Do you recognize where they shop?

Fashion Is Both Familiar and New

Wearing what is “in fashion” is a way to appear accepted by an identifiable societal group or subculture. This might involve the products selected to be worn, how they are worn on the body, or the different ways of combining them on the body to achieve a particular look. Every group, or target market, will select from what they accept as fashion in the marketplace and from their own ingenuity in putting together a look. The acceptable look may be more evolution than revolution.

In the introduction of any new look, it is important to recognize what is familiar and what is new. It’s a bit like the adage that you must understand the ground rules of a style before you can break those rules. Acknowledging how the rules are broken means you have taken the first step towards understanding the concept.

Consumers may differ in the amount of familiar and new they tolerate. You must understand the tension that may result from wanting some measure of both the familiar and the new. Rarely does a new look appear that is completely new, demanding a total replacement. What is up-to-date is usually a combination of the familiar and the new. You may, for example, see a style that is familiar but with a few noticeable new details—a color or texture or a different relation to the body, such as a more fitted or loose look or cutouts in the fabric that expose the body in new ways.

A disruption of a fashion trend is rarely all new unless there is a jolt that causes a complete change in direction. This has occurred a few times in our history, when a war or pandemic has limited the normal process of acquisition and evolutionary change in what is accepted as up-to-date. In such a case, prior limitations and pent-up demand can influence a more urgent need for a new look following the disruption.

Fashion and Boredom

You may ask why humans need to update the way they look, according to the zeitgeist? Laver (1973) suggests that, with time, response to what the eye sees may vary from taking delight with the new to eventual boredom. A style that has immediately passed from fashion may thus be perceived as out-of-date, might even be considered disgusting and ugly. Years later, however, the same or a similar style may be perceived as attractive and pleasurable once again, because enough time has passed for it to be perceived as new. This cycle means the style appears new to a different generation, 15–20 years later.

This need for a refresh may be why we have forecasters who focus on evolutionary details such as color or texture. Color forecasters analyze the color wheel to develop a color or colors of the year. Textile forecasters focus on the qualities of the fabric they recommend, such as a fluid drape or an animal print. This type of forecasting helps the apparel industry focus and coordinate what is offered and provide users with a small but possibly needed and understandable refresh.

Fashion and Trend Forecasting

While trend forecasting is about predicting the future, Faith Popcorn defines the future as starting now. As we discussed earlier, she has coined the term “cultural brailing” to describe learning about the bumps in the culture through a combination of astute observation and intuition. This process is about using your senses: sight, taste, hearing. It could be a matter, for example, of walking into a retail store and noticing the lighting and music, feeling the different textures, and fully immersing yourself into whatever the environment offers. Brailing is difficult and all-consuming, something you must do wherever you are and no matter who is with you. You must ask the questions and be aware of the answers: What change am I aware of, where did it originate, and why is it emerging at this time? Then, what products could be associated with the trend, how long will it last, and what groups will accept it?

You will need to be open to new ideas, curious, and aware of what is happening around you, observing changes in user behaviors and thinking critically about relationships occurring in society. You will need to find ways to expose yourself to new experiences, observe those taking part in unfamiliar events and considering how they might influence the zeitgeist. Above all, you will need to develop your curiosity enough to reflect upon the data you collect and, ultimately, the meaning of it all.

You will also need the ability to reflect on current societal trends, how they relate to the meaning of products, and their relationship with the body and the environment. There are assumptions that we all live with and need to question. In the 20th century, for example, there was an assumption that gender could be determined by the clothing you wore. Categories of clothing in the marketplace characterized femaleness and maleness. In the 21st century, those categories are blurring. Men are wearing colors and shapes that previously were considered female, and vice versa. And emerging categories, such as androgynous and transgender, defy the assumption that genders should be distinguished by their appearances. The pandemic changed a different assumption. Before, those working in the public sphere may have thought they must wear something different each day, and must accept wearing products that were uncomfortable. With many people working at home and in private, the pandemic changed this assumption, and comfort took priority over variety and discomfort. We’re now faced with what this means to the products offered in the marketplace.

Remember that fashion may refer to many aspects of our lifestyle, including up-to-date furnishings, cars, interiors, restaurants, and food venues, and even how we think and act and what we do in our leisure time. Quilting, for example, is a leisure activity that has come back into fashion. The trend forecaster who recognizes this current interest may understand the trend as being influenced by societal needs and relationships—what Faith Popcorn calls “cocooning,” referring to the cozy, comfortable things people do because of “the need to protect oneself from the harsh, unpredictable realities of the outside world” (Faith Popcorn’s Brain Reserve, 2020).

Trend Challenge

As you think of fashion more broadly, consider a venue that you haven’t considered fashionable before, like kitchen remodels or food served at a restaurant. Describe the current practice, the length of time it has been a current practice, and perhaps an influence on that practice.

As we look to discover trends that involve a change in the direction of a society and of groups within a society, it is useful to consider fashion more broadly. Cultural brailing is about being constantly aware of these directional changes and of how they may influence the collective marketplace.

References

Barthes, R. (1990). The fashion system. Translated by M. Ward and R. Howard. University of California Press.

Black, S. (2008). Eco-chic: The fashion paradox. Black Dog Publishing.

Blumer, H. (1969). Fashion: From class differentiation to collective selection. The Sociological Quarterly. 10:3, 275–291.

DeLong, M., & Bang, H. (2021). Patterns of dressing and wardrobe practices of women 55+ years living in Minnesota. Fashion Practice. 13.1

DeLong, M., Bang, H. & Gibson, L. (2018). Comparison of patterns of dressing for two generations within a local context. Fashion, Style & Popular Culture. 6(1).

DeLong, M. (1998). 2nd Ed. The way We look, dress and aesthetics. Fairchild.

DeLong, M., Minshall, B., & Larntz, K. (1986). Use of schema for evaluating consumer response to an ppparel product. Clothing & Textiles Research Journal, 5, 17–26.

Entwistle, J. (2001). The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress and Modern Social Theory (2nd ed.). Polity Press.

Fletcher, K. (2008). Sustainable Fashion and Textiles, Design Journeys, Earthscan.

Hethorn, J., & Ulasewics, C. (2008). Sustainable Fashion: Why Now? A Conversation Exploring Issues, Practices, and Possibilities. Fairchild Publications.

Kaiser, S. (2013). Fashion and Cultural. Berg Publishers.

Laver, J. (1973). Taste and fashion since the French Revolution. In G. Wills and D. Midgley, Eds. Fashion Marketing. George Allen Irwin.

Loschek, I. (2009). When clothes become fashion. Design and Innovation Systems. Berg Fashion Library. DOI: 10.2752/978184883581/WHNCLOTHBECOMFASH0004

Nystrom, P. (1928). The Economics of fashion. Roland Press.

Polhemus T. (1994). Streetstyle: From sidewalk to catwalk. Thames & Hudson.

Popcorn, F. (2020). Welcome to 2030: Come cocoon with me. https://faithpopcorn.com/trendblog/articles/post/welcome-to-2030/

Popcorn, F. (2010). YouTube video. https://youtu.be/5-KiWK9eg4o

Postrel, V. (2003). The substance of style: How the rise of aesthetic value is remaking commerce culture and consciousness. Harper Collins.

Rubenstein, H. (2014). The Tory Effect. Delta Sky. May, 2014. pp. 81–83