Chapter 2 – Understanding your Aesthetic Response

Marilyn Revell DeLong

To become a trend forecaster, you must first examine your own aesthetic response to designed products. This involves examining your current likes and dislikes, your ongoing preferences, your needs and desires, your biases, and your assumptions—all of what makes the total of your “ME” response. What you bring to the table is important—your unique experiences, your attitudes, and your behaviors as you engage in the world around you. In other words, as an observer of trends, you need to know yourself and to recognize and reflect upon your aesthetic response. This becomes a basis for understanding others.

Attending to Form and Meaning

An aesthetic response includes its resulting experiences, such as what one selects as an expression of preference (DeLong, 1998). A person may focus their preference for a particular product on the way it looks, such as its color or texture, the way it fits and moves with the body, or how it makes the person feel up-to-date. Or they may simply focus on the way the product functions in use, and not be aware of its other attributes.

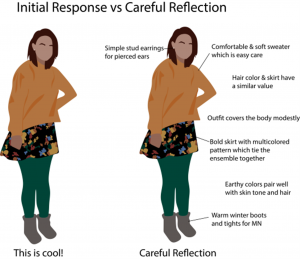

An individual’s aesthetic response is often not brought to a level of awareness, and making quick judgements of “I like it” or “I don’t like it” becomes a habitual shortcut. Your aesthetic response, however, is much deeper than these surface judgements, and is based on the sum of influences of your past experiences, present expectations, attitudes, and underlying preferences. What you pay attention to, whether focused narrowly or ever expanding, is critical to your understanding of yourself and your relation to trends.

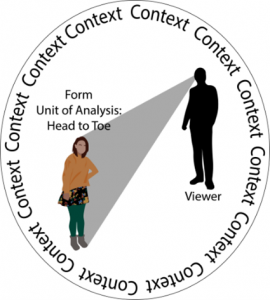

The outcome of your aesthetic response is influenced by your reflections upon the form, viewer, and viewing contexts. We will consider each separately while, at the same time, realizing the importance of their interactions to create meaning.

Form

Form is the distinctive arrangement of colors, textures, lines, and shapes created by the interaction of the body with all that is put on or done to manipulate or modify the body (DeLong, 1998). Attending to form means paying attention to all the design elements and their interactions and relationships, as we will discuss in a later chapter.

Unit of Analysis For the best understanding of the aesthetic response, the unit to analyze must be the entire form—what we consider as the whole designed entity. If examining the design of an interior room, for example, the unit of analysis would include the furniture, floor covering, and wall coverings—all that is within the viewer’s scan.

When examining your look or appearance, the unit of analysis is the entire body from head to toe, including what is attached or placed upon it (e.g., hats, eyeglasses, hosiery, jackets), what may be inserted (e.g., earrings that fit into pierced ears), and how it is modified (e.g., hair styles, including hair color, texture, and shaping, and tattoos). Though your aesthetic response includes all the senses, we are primarily focused upon the viewing relationships usually involved in trend forecasting. But remember that your response also involves your other senses. Think of the sounds made when the body is moving—the rustle of a taffeta skirt, or the click of leather boots a cement pavement.

You may focus on the “form” as a body view when not in motion. This body view is what you see in a catalog or a photograph. When a body view is what is available for viewing, the silhouette and limitations of movement must be considered. Sometimes this limitation of what can be seen is so prevalent that it is labeled, i.e. the pandemic view of only the upper body in a Zoom meeting.

Trend Challenge

Select a head-to-toe look from a selfie or some other image that represents you and what you would wear. Think about the head-to-toe look of each of the following as related to the body:

Which items are attached to your body? (e.g., shoes, T-shirt, hair band)

Which items are inserted in your body? (e.g., tattoos, earrings, studs)

Which items modify your body or increase its functions? (e.g., hair dye, bras, mobile phone)

If the unit of analysis is limited to separate and discrete products, the viewer can get caught up in one product. If the product is footwear, for example, you learn something when you examine a shoe for its heel height, color, and textural details—but only about shoes. Unless you also consider how this footwear affects the whole form and the relationships involved, something is missing in your understanding of the aesthetic response.

Viewing Relationships within the Form

Individual products, such as shoes, handbags, or trousers, interact with the body to result in a look or appearance. The unit of analysis includes how products look on the body in its entirety. This analysis involves recognizing details of surfaces (e.g., color and texture) and perceptible lines and shapes (e.g., sleeves and silhouettes), along with relations of part or parts to the whole (e.g., the relation of surface details of color and texture to the silhouette). Analysis of the entire unit of the form must include the information received from the interaction of the body and the wearer, including body proportions, hair shape and texture, and skin color and texture—every physical aspect present. Also note how the viewing relationships within the form attracts and then holds attention. The character of these details, and how they are combined and arranged, provide definition and distinctiveness to the form.

Meaning Related to the Form

In the study of trends, the elements that provide meaning in viewing the form require attention and understanding. Norman (2004) defines meaning as involving three levels of processing our response to products. Level 1 is visceral: our immediate impression, and the initial impact of the appearance. This level involves our first rapid and automatic judgement of what we think is good and bad: “I like it” or “I don’t like it.” Level 2 is behavioral, and involves our experience with a product; how well, for example, will the product function? This level involves actions we habitually take without much conscious thought, such as driving an automobile, playing an instrument, or using a computer keyboard while contemplating something else. In terms of appearance, Level 2 might include be the pleasure you gain from your use of products, and the preferences you have developed over time for colors and textures. Level 3 is reflective, the home of your conscious thought and memories that relate to your life experiences and cultural values. This level is where we learn new concepts and how to contemplate and understand meaning. You may, for instance, reflect upon your past and your experience of hating a product, and discover that, through further exposure and reflection, you can tolerate it.

The effective trend forecaster learns to consider responses from all three levels, and to reflect upon differences in user response. These levels interact continuously. And while a user’s processing can begin at any level, it is at the reflective level where interactions with the user matter most. This is where the trend forecaster can become aware of and sensitive to differences among users (Norman, 2004).

Your Schema. Research shows that you hold an image, or schema, in your mind that provides you with an instant judgement of “I like it” or “I don’t like it” (Norman’s Level l). This schema relates to what you pay attention to, and offers an instant shortcut past the myriad of images available to you that could overwhelm your attention. We make categories and code what is important to us. If what is new and up-to-date is important to you, it will become a part of your schema (DeLong et al., 1986). Your schema is ever changing based upon new images you become aware of. It continually evolves and changes in response to what you are currently experiencing.

What you pay attention to affects your schema—the image in your minds’ eye—and this plays a part in what becomes your aesthetic response. Under normal circumstances, a schema is mostly intuitive and not necessarily a part of conscious thinking. Your response is a rapid means of reaching a judgement that is dependent upon what attracts your attention. As you respond to various products, familiar patterns, or styles, become a critical part of your schema (Level 2).

As a trend forecaster, however, you must train yourself to notice and reflect on such things as new color combinations or design details that express the body in a new way. In other words, you need to be aware of what has become familiar and what is new. You can train yourself to consciously pay attention to what you pay attention to. You can then expand and deepen your schema. By being aware of your patterns of attention, you can become more attuned to what you experience and its relation to yourself and your world. Our response to the form is understood as involving all three levels, but the reflective level is where you can begin to understand meaning.

As a trend forecaster, you must slow down your response to become more reflective. This takes time, and an awakening of curiosity. Meaning can occur within the form through its expressive visual effect. An expression that reflects simplicity, for example, may arise from a simple and coherent look created by one focal point and an analogous color scheme that leads your eye based upon a simple shape of the silhouette. If you become aware of such a pattern in your viewing, you may learn to prefer this look, and it may become part of your schema. Or an expression of femininity (Level 3) may arise because of combinations you have learned from past experience (Level 2). Your definition of a feminine look arises from your reflection based upon meaning derived from the interaction of certain colors, textures, lines, and shapes, such as light values and muted hues, curvilinear lines, small shapes, and smooth textures that define the wearer’s body.

Reflective meanings also arise from viewing the form and its associations with past experiences and emotions. A mature, experienced viewer, for instance, may reflect upon a product that reminds him of what he wore as a teenager or upon color popular that invokes a previous decade. Or a viewer may smile from seeing bright ,cheerful colors on a small child and remember skipping along the street in the same way. Though individual, these reflections may relate to associations made by others because of this common experience.

Viewer

Aesthetic response is dependent upon the viewer of the form. Generally, the viewer is the observer of the form, but motive becomes important here. The viewer may also, for example, be the user, the person wearing an ensemble who becomes the viewer when looking into a mirror to assess their appearance. The viewer may also be the consumer who is motivated by shopping for a new purchase. Each type of brings individual traits such as gender, age, personal aptitudes and skills, knowledge, experience, and likes and dislikes (DeLong, 1998), all of which affect their aesthetic response.

Great pleasure may be found in recognizing good design, or even in asking questions such as “What product gives me pleasure?” and “What message do I want to give to others?” Learning through personal experiences of good design related to ourselves can be translated into understanding others. Have you ever said to a friend, “But that is so YOU!,” and in responding in this way, recognized that while it is not something you would select to wear, it is perfect for your friend? It’s fun to reflect upon our own preferences and experiences. Learning how to gauge your aesthetic response compared to that of someone else is good practice, and is initiated at the reflective Level 3 of Norman’s processing model (2004). As you can imagine, processing our responses at Level 3 requires the greatest amount of effort and creativity.

The viewer who understands preference can recognize when a fashionable image provokes a favorable collective response from self and others. You might, for example, prefer blue, and know that a certain blue is forecasted to be very popular in the coming season. From your data analysis of the U.S. market, you also know that your target market prefers the hue as well. It is not a stretch for a trend forecaster to promote a color related to what is current with both the zeitgeist and the target market—a winning strategy.

Understanding the Familiar and the New

The viewer who brings patterns from their experiences to their present aesthetic response is confronted with expectations of both the familiar and the new. The past influences the present and the evolving nature of one’s schema. To be understood, this schema needs to become part of consciousness. Perceived patterns that form a schema become an aspect of the expectations brought to the next experience (DeLong et al., 1986). Reflecting upon viewer expectations is important in understanding both your aesthetic response and that of others—in understanding, for example, how different combinations of lines, shapes, colors, and textures are preferred in summer and winter seasons. Though certain expectations have developed and become familiar over time, you must be aware of and try to understand what is new, what is different from the familiar.

This relationship of familiar and new can vary depending upon your target market. A change in a familiar product category may cause you to change that product’s focus. A product that previously blended in as part of an entire ensemble, for example, might now be made a focal point, requiring a conceptual change in how we recognize what could be new for that product in a particular market.

As a trend forecaster, you must be skilled in finding the right combination of the familiar and new for the user. Training yourself to look for what could be new in a product’s design means recognizing what is familiar and how that is changing. For example, the way a jacket closely fits the body has become familiar. But the familiar look of a closely fitting jacket may no longer be perceived as up-to-date when the jacket either abruptly or gradually becomes less fitted; this requires a change in focus from the familiar.

Over time, changes in the physical nature of an individual may influence how they appear up-to-date. This is a continual challenge. The child has the opportunity for change in appearance simply because clothes are outgrown before they wear out. A person whose body shape has not changed in years, however, may not be aware of needing to make strategic selections to continue to appear up-to-date. While changes can occur as part of the collective demographic, they are still experienced individually in terms of timing and duration: one’s age or personal health may change body weight or physical coloring.

Context

As used here, context is considered in a broad sense. It includes both the physical space that immediately surrounds the form and the broader cultural milieu—the aspects of time and place important within a culture.

First consider the immediate physical space surrounding the form. Think, for instance, about how adjacent surface colors and textures are influenced by the immediate surround in the display of a product, such as how colors bounce off shiny surfaces or are absorbed. Try to see a color in daylight instead of artificial light; through experience, you may have discovered that this matters in matching two surfaces. While those such as fashion photographers and designers of theater costuming are especially aware of these differences in aesthetic response based upon control of these immediately adjacent surroundings, this awareness of physical space is also important for the trend forecaster.

The broader context also includes the time, place, and current and past values and ideals held by the viewer(s) within their society (DeLong, 1998). Appearing up-to-date is an evaluative criterion of aesthetics related to the context of a particular time, place, and situation. The look accepted by a selected societal group at a given time is an expression of currency: current technology, current cultural events, and current designer creativity. Appropriateness of the look planned for that specific time and place—for the context of situation and event—may relate to what we value, and to the nature of what appears up-to-date and just right for this season. Recognizing these interrelationships within a particular context of time and place is particularly important when considering markets other than the one to which you belong. A trend forecaster who ignores such factors runs the risk of offending the target market or, worse, causing legal or public relations issues.

Context involves meanings that can become a focus in viewing, especially as they relate to what is valued by a certain group. Such focus may be on just one product, and it is important to recognize the connotations of meaning related to that product. Understand that what we value as a group can take on nuanced meaning. For teenagers, for example, blue jeans can become a valued product focus, and they pay attention to details and meanings that others might not see or understand. The teenager may ask: Which pair of jeans are appropriate to wear for a certain situation? I asked a group of teenagers how many pairs of blue jeans they had in their wardrobes, and was surprised by the number—15 on average. When I asked why so many, the conversation turned to all the nuanced ways in which the owners perceived and valued variations in fit, stitching, embellishments, and modifications. Being “in the know” about teenagers and the nuance of meanings they ascribe to their jeans is vital to understanding that market.

Also vital, however, are the ways in which a product interacts with other products and how these products are worn. Through the products we select to wear together, we suggest our age, gender, or occupation (demographics), as well as how much attention we would like from others (psychographics). In the jeans example, we need to look not just at the product itself, but at what the teenagers are wearing with their jeans and what they are doing while wearing them.

Context also includes the meaning associated with cultural traditions. Use of the same color in different cultural contexts may change its meaning. In the U.S., for example, it is traditional for brides to wear white. In Korea, however, brides traditionally wear red; white is traditionally worn for funerals, and is only adopted for weddings when the bride wishes to emphasize a cross-cultural expression.

What does this broad examination of aesthetic response have to do with explanations about meaning? As we think about Norman’s three levels of processing, we can now apply the concept to what makes us exclaim, WOW!

What Is Behind this “WOW!”

Let’s explore what attracts your attention enough to make you exclaim “WOW.” At the visceral stage, aesthetics involves one’s immediate reaction of pleasure and satisfaction derived from sight, smell, touch, hearing, taste, and sense of being. But one’s response also occurs on the behavioral level that includes the sum of past experiences and preferences and what you have come to value—referencing your schema. Stop and ask yourself what is behind your WOW! You may never probe further about why or what details made such a positive response. But the more reflective you are, the more aware of your past experiences, and the more varied and diverse your exposure has been, the more likely you are to be open to change.

You can’t, however, stop with only understanding your own response. As you think about trend forecasting, the need to pursue and understand more than your individual response will become apparent. Forecasting trends is all about being open to what is new, and sometimes even strange. Understanding what we value, both in form and physicality as well as in the messages we express, requires reflection. But as you notice something strange and unfamiliar, you may ask, how do I move from understanding the form to understanding values, especially those of another person?

Using an understanding of your own response to understand another’s WOW response is the start. You’ll need to listen and understand WOW from their perspective. Ask the question, “Do I agree?” If the answer is no, ask “How and why do I disagree? Am I open to understanding their WOW even if it is not my response?” Understanding any group beyond your own requires you to engage in discovery, as members of that group may not always be reflective about their aesthetic response, and you may need to probe to understand what they value, and examine how that response might relate to a collective point of view. Be curious and open to others when they express their responses.

Trend Challenge

Return to your previous selection of a head-to-toe look from a selfie or some other image that represents you and what you wear. Which elements of your appearance choices are important to you? For example, do you wear glasses or contact lenses? What does that choice say about you? Identify at least five important appearance choices, and describe how each choice makes you appear up-to-date.

Critique for Trend-Spotting Savvy

A good critique requires the ability to recognize the subjective nature of your response and then justify it through reasoning and reflection. This is quite different than the rush to judgment that often occurs when one becomes satisfied with “I like it” as a sufficient response. A pleasurable WOW experience may occur without a conscious understanding of how and why it took place. Much in understanding aesthetics and how it relates to trend forecasting comes from your ability to engage in good and useful critique.

To understand trends, you need to move to thoughtful critique, which involves being aware of and expressing the reasons for your aesthetic response. Focus first on your reflective response on the designed product. Then explore the patterns and characteristics of the product that provide meaning for you—how it is used, for example, and how it relates to your lifestyle. Then, if you can move on to how the product will relate to the cultural context, you can develop a more professional stance involving analysis and critique.

Challenge Trend Thinking Activity

Select a head-to-toe example of a form that you consider to be up-to-date and that includes one or more products that attract your attention. Now slow your viewing. Describe the form as thoroughly as you can. Examine the words you use, and note those that would be understood by others and those that would be understood only by you.

Critique in Forecasting a Trend

When engaged in critique of a product that you consider to be trending, it is important to understand your own subjectivity. One way to understand what is valued is to learn to be curious, and to create an inner dialogue with what you see, touch, and smell. This includes your instantaneous reaction, any rush to judgment (liking or hating the product), all the way to reflection. You may learn about another’s values and decide whether you agree or disagree with what they think and feel. To make a judgment, however, you must engage in critique: an open and inner dialog about the product and its relation to the whole form. Ideally, you will examine the reasons for such peak experiences and how they relate to what is valued. You may express your “WOW” because of soft-to-the-touch fabric quality, impeccable tailoring, or the way in which colors are put together, or because of the care in which a friend has chosen to appear at a special event or has simply a pulled together look that captures the essence of the zeitgeist.

Learning how to do a thoughtful critique brings us closer to understanding the complexities of what we experience—the layers of our first response, affirmation of the product’s use, and the ways in which it fits into its intended cultural context. Analysis and critique require experience with in-depth and systematic examination. Analysis of any product starts with focus on the form and moves to relational aspects of viewer and of contextual perspectives within a culture. We’ve defined form as the unit of analysis—the “look” or appearance of the human body with all that is placed upon it, all that modifies, enhances, and disguises it. This probing is necessary for developing the educated eye and seasoned response that are so important in trend forecasting.

To be a great trend forecaster you want to be the first to spot a trend. For this, observation and a measure of intuition are key. American forecaster Faith Popcorn calls this cultural brailing—fully immersing yourself, with all your senses, to track changes in how consumers live. Brailing involves being hyper-observant and alert to any new thing that widens the horizon, and thinking outside the box. It combines observation with intuition. And it requires research—taking pictures of what you see on the street; going to museums, galleries, and trade shows; taking notes. Your research does not need to be about fashion itself; it can be about technology, architecture, or graphics. It should also involve using the internet, looking at blogs, news sources, and trend-forecasting websites such as WGSN and Trendcouncil. All of these sources can help you discover trends, as a trend can start and emerge from anywhere.

Understanding How Critique Helps to Assess the Marketplace

As a trend forecaster, you can make your personal response and schema work for you. They need to become part of your conscious viewing and your continual exposure to new experiences. You need to be able to express the form and meaning relationships in what you see, and to open yourself to examine the implications of new experiences that broaden your aesthetic response. Setting up a dialogue with yourself helps you learn how to use your schema for professional reasons. While you may want to forecast trends for a niche market like yourself, you may also find yourself forecasting trends for users unlike yourself. In both instances, you need to understand more deeply your own aesthetic responses.

- Use your schema as a guide to develop trends for a niche market. You will be good at working with this market if your knowledge and understanding of the similarities to your own likes and dislikes, behaviors, and past experiences reflect this market niche. For example, regarding her rapid rise to success in the apparel industry, Tory Burch explains: “it was a tremendous amount of work to find that one opening, that niche where we knew we would fit. We specifically targeted that customer who wanted fine crafted things that didn’t cost a fortune. We knew that woman was out there but didn’t want to wait for her to come to us. We decided we’d have to reach out directly to her.” Explaining what attracted Tory Burch to this particular customer, she said: “Like minds, perhaps. As a woman, it’s natural to want to design the clothes that I personally want to wear, because they suit my work, they suit my life, they suit my age. And in doing so, you want to celebrate and incorporate the inspirations that excite and inspire you” (Rubenstein, 2014, p.82). Tory Burch found a market by understanding the trend in others that related to her own wants and needs. Her tagline, found on her website, is:

Tory Burch is an American lifestyle brand that embodies the personal style and sensibility of its Chairman, CEO and Designer, Tory Burch. Launched in February 2004, the collection, known for color, print and eclectic details, includes ready-to-wear, shoes, handbags, accessories, watches, home, and beauty.

You will need to practice forecasting trends for niche markets—first, those like your own, and then branching out to other markets.

- Consider broadening your perspective beyond your own likes, dislikes, and preferences. Learning to know when you are responding from your own perspective, you realize that your preferences are yours and not another’s. By understanding yourself well enough to separate your own preferences from those of others, you are free to listen to and learn from your potential users about their schema and preferences and become more focused in serving their needs, wants, and desires.

Not everyone is going to find a niche for their professional energies and dreams that appeals directly to their own likes and dislikes, as Tory Burch did. You may find yourself marketing a product for children whose likes and cultural aspirations are different from yours. Or you may find yourself studying the demographic trending of an aging population, and developing a niche that relates to their likes and dislikes, behaviors, and past experiences. It is important to be open to these other perspectives—particularly in the global marketplace of the twenty-first century. Fashion professionals must push themselves beyond their own comfort zone or frame of reference into understanding the market segments they will serve. Engaging in critique is the beginning of understanding aesthetics and what will make for a successful market niche.

Shared meaning =relationships for communication

Communication means shared meaning, and the trend forecaster must be skilled at understanding and communicating such relationships. One way to communicate effectively is to think about your intended audience as a target market for the design and distribution of products. As a trend forecaster, put yourself in the shoes of someone vastly different from you and predict the products they will need and want.

Communication means shared meaning, and the trend forecaster must be skilled at understanding and communicating such relationships. One way to communicate effectively is to think about your intended audience as a target market for the design and distribution of products. As a trend forecaster, put yourself in the shoes of someone vastly different from you and predict the products they will need and want.

Persona describes what many in the apparel industry refer to as the typical individual they imagine for their target market. This persona is often named and described to include demographics such as age, gender, body size, location, (geographics), employment, activities, and psychographics such as likes, dislikes, and ongoing preferences. This link to the individual user continually references an intended audience, and aids those in the industry to come together in their thinking about form and meaning relationships in the marketplace.

Trend Challenge

Think of a market category in which you enjoy shopping. Create a persona for that market. Consider a name, gender, activities, and lifestyle help you better focus on and understand that market. A persona might be something like: Lizzy is 30 years old, with two children; she is always busy with lots of activities both for her children and herself. Then consider how that persona influences the products you might offer.

Trends as Link to Context and Communication

Trends link a product to the historical context of time and location. Much of what we find offered in the marketplace is familiar, with only a few changes in details. When a product evolves from one season to the next, for example, it may simply have a new color or a slight change in shape. At times, however, a cultural shift becomes influential in changing how people see themselves. Social media is this type of cultural shift, influencing new products and the speed at which products must change. As exposure to new products increases, our propensity for boredom with these products increases as well.

When an abrupt shift occurs within a culture, it may result in an abrupt change in what is offered in the marketplace. In the U.S., for example, World War II created a major shift in how men and women viewed themselves. Suddenly, men were off serving their country and women became part of the war effort with administrative or service-related jobs. These changes created a shift in thinking, and put marriage and family on hold. At the end of the war, when servicemen returned home, both men and women wanted to marry and start a family. Restrictions on fabric lifted. The “New Look” was so called because it signaled a definite shift in clothing products on the market for women. The practical and economical look of women during the war changed dramatically to a look that emphasized the curvatures of the feminine body, with dropped shoulders, nipped-in waistlines, and longer, more flowing skirts. The male look changed. The man in uniform, or in the grey flannel suit, moved to the suburbs to marry and start a family. Suburban living, with casual pastimes such as barbecue, outdoor grilling, and golf, created a market for men’s casual clothing. These trends went well beyond clothing as well. With the shift to a suburban lifestyle came an increased interest in casual entertainment. Products like disposable paper and plastic dinnerware (with their quick clean-up) became very attractive. A large, new market opened with this societal shift.

For trend forecasters, understanding abrupt and broad societal shifts like these requires an knowledge of the complexities of aesthetic response in order to consider the opportunities for change.

Trend Challenge

The pandemic has been a major societal shift. In your notebook, record two products whose use you saw change during the pandemic (e.g., masks, yoga pants, roller skates). Forecasting for the coming year, what do you think might be modified in those products? In your notebook, make a note of these modifications, or find and create images illustrating them, and describe why you think the modifications could occur.

Trends are always referenced from what has happened or is happening within a culture. Knowledge of your own aesthetic response is a central point of reference. Understanding this response as it relates to your target user allows you to understand what has become familiar and accepted, both in the short term and long term within the cultural context.

References

Black, S. (2008). Eco-chic: The fashion paradox. Black Dog Publishing.

Blumer, H. (1969). Fashion: From class differentiation to collective selection.The Sociological Quarterly. 10:3, 275–291.

DeLong, M. (1998). 2nd Ed. The way we look: Dress and aesthetics. Fairchild.

DeLong, M., Minshall, B., & Larntz, K.( 1986). Use of schema for evaluating consumer response to an apparel product. Clothing & Textiles Research Journal, 5, 17–26.

Fletcher, K. (2008). Sustainable fashion and textiles: Design journeys. Earthscan.

Hethorn, J., & Ulasewics, C. (2008.) Sustainable fashion: Why now? A conversation exploring issues, practices, and possibilities. Fairchild Publications.

Laver, J. (1973). Taste and fashion since the French Revolution. In G. Wills and D. Midgley, Eds. Fashion Marketing. George Allen Irwin.

Loschek, I. (2009). When clothes become fashion. Design and innovation systems. Berg Fashion Library. DOI: 10.2752/978184883581/WHNCLOTHBECOMFASH0004

Norman, D. (2004). Emotional design: Why we love (or hate) everyday things. Basic Books.

Nystrom, P. (1928). The economics of fashion. Roland Press.

Polhemus T. (1994). Streetstyle: From sidewalk to catwalk. Thames & Hudson.

Popcorn, F. (2020). Welcome to 2030: Come cocoon with me. https://faithpopcorn.com/trendblog/articles/post/welcome-to-2030/

Popcorn, F. (2010). YouTube video. https://youtu.be/5-KiWK9eg4o

Postrel, V. (2003). The substance of style: How the rise of aesthetic value is remaking commerce culture and consciousness. Harper Collins.

Rubenstein, H. (2014). The Tory effect. Delta Sky. pp. 81–83.