Affordable Content Models

Chapter 16 – Inclusive Access: Who, What, When, Where, How, and Why?

Cheryl Cuillier

by Cheryl Cuillier, University of Arizona (bio)

In the college textbook landscape, inclusive access programs are expanding rapidly. This chapter explores the evolution of inclusive access and the model’s possible advantages and disadvantages, considering perspectives of publishers, campus stores, faculty, students, and open educational resource (OER) advocates. Using the University of Arizona (UA) BookStores’ inclusive access pilot as a case study, I also share the lessons we have learned. UA anecdotes come from 2017 interviews with Cindy Hawk, Assistant Director of the UA BookStores; Mark Felix, Director of Instructional Services in the Office of Instruction & Assessment; Management Information Systems Professor Bill Neumann; and Valeria Pietz, eLearning and Multimedia Services Team Director in the Eller College of Management.

While the details may vary by publisher, vendor, retailer, or institution, inclusive access generally works like this: Students receive access to digital course materials on or before the first day of class.

While the details may vary by publisher, vendor, retailer, or institution, inclusive access generally works like this: Students receive access to digital course materials on or before the first day of class. Content is usually linked in the campus learning management system (LMS). Access for enrolled students is free during a brief opt-out period at the beginning of the course; if students opt out of buying the inclusive access content by the deadline, their access disappears. If they do not opt out, access continues and they are automatically charged for the content. Because opt-out rates tend to be low, publishers say they can afford to offer volume discounts at substantial savings (“as much as 70 percent” [Dimeo, 2017, Michael Hale section, para. 8]). Student access to purchased materials ends at a length of time negotiated with the publisher.

These programs are known by a variety of names. Publishers McGraw-Hill Education, and Wiley use the term inclusive access, as do content delivery providers VitalSource and RedShelf. Macmillan calls its digital discount program Macmillan Learning Ready. Pearson referred to the model as both ALL-INclusive and Digital Direct Access. Unizin dubbed it the All Students Acquire model. The Mizzou Store at the University of Missouri calls it AutoAccess. At San Diego State University, the program goes by Immediate Access. Hinds (Miss.) Community College calls it Instant Access. Follett named its platform includED, and Barnes & Noble College uses the term First Day. According to Ruth (2017), programs are also referred to as “day-one access,” “digital discount,” or “enterprise solutions” (para. 3).pearson

To reduce confusion, I will refer to the model throughout this chapter as inclusive access (the name of the UA BookStores’ program). I acknowledge that this term is controversial. According to Nicole Allen, Director of Open Education for the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC), “inclusive access” is a misnomer: “It’s the opposite of inclusive, because it is premised on publishers controlling when, where and for how long students have access to their materials, and denying access unless they pay for it” (as cited in McKenzie, 2017, Inclusive or Exclusive? section, para. 1). Advocates of open textbooks, which are freely available online and allow customization and perpetual access, say “inclusive access” is a more fitting moniker for OERs than for digital commercial content. Compared with traditionally copyrighted materials from publishers, OERs offer expanded capabilities and possibilities, according to David Wiley, Chief Academic Officer of Lumen Learning (2017). “OER broadens access in a way that is actually inclusive,” said Rajiv Jhangiani (2017), a University Teaching Fellow in Open Studies and psychology professor at Kwantlen Polytechnic University. “The OER approach enhances access and agency in a manner that serves social justice and inspires pedagogical innovation” (para. 5).

No matter the name, the model of first-day access to commercial digital content is clearly gaining traction with publishers, college stores, and faculty.

Case Study: UA BookStores

The UA BookStores began piloting inclusive access in Fall 2016. Growth has been tremendous, with a nearly tenfold increase in the number of participating students over the next year. In Fall 2017, 4.5% (450) of the UA’s 10,000 sections connected to course sites in our D2L Brightspace LMS used inclusive access (this figure differs from the number of courses in Figure 1 because some courses had multiple sections). Over three semesters, the UA BookStores’ estimates for total student savings exceeded $2 million. UA students have until the course’s add/drop date to opt out of purchasing the digital content; the percentage choosing not to buy the content through inclusive access has ranged from 3.9% in Spring 2017 to 7.6% in Fall 2017.

| semester | # courses | # students | opt-out rate | estimated savings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fall 2016 | 7 | 2,151 | 4% | $111,000 |

| Spring 2017 | 21 | 5,324 | 3.9% | $291,000 |

| Fall 2017 | 95 | 22,128 | 7.6% | $1,671,400 |

Data from UA BookStores. Estimated savings are based

on comparisons to new print prices.

At the UA, inclusive access is used on a textbook-by-textbook basis, and faculty are given the option to participate. By Spring 2018, the UA BookStores had inclusive access agreements with nine publishers and two platforms (RedShelf and VitalSource). Technology from Verba, which was acquired by VitalSource in 2017, is used for tracking opt-outs, delivering courseware, and other functions, and Verba is considered a separate integration from an IT standpoint. Price negotiations with these publishers and vendors are handled by the UA BookStores, although sometimes faculty negotiate as well. (In other inclusive access models, publishers may negotiate directly with the institution, cutting the campus store out of the process [Esposito, 2017]).

As a campus-owned entity, the UA BookStores give profits back to the UA community by supporting campus organizations, initiatives, and scholarships (2017, “How do we do more?” section). The BookStores partner with the UA Libraries on textbook affordability initiatives, including the use of OERs and library-licensed ebooks (see This Chapter for more details). OERs and inclusive access are not mutually exclusive. OpenStax, for example, makes its open textbooks available through inclusive access via VitalSource and RedShelf (Ruth, 2017, para. 1).

Inclusive Access on Other Campuses

Other universities were early pioneers of inclusive access. According to Straumsheim (2016), Indiana University (IU) began piloting its eText initiative in 2009 (para. 2). The program has grown 50% year-over-year, been part of 2,600 course sections, and saved students an estimated $3.5 million in the 2016–17 academic year alone, said Brad Wheeler, Vice President for IT (as cited in Indiana University, 2017, para. 2 & 8). In 2013, Western Kentucky University was among the first institutions in the nation to start an inclusive access program (Angelo, 2018, p. 23). The UC Davis Stores at the University of California, Davis, and the Mizzou Store at the University of Missouri both began using inclusive access in 2014. Digital textbooks are now used by about 17,000 UC Davis students per term, and since 2014 inclusive access has saved students nearly $7 million compared to the price of new print textbooks, said Jason Lorgan, executive director of Campus Recreation, Memorial Union and UC Davis Stores (as cited in VitalSource, 2017a, para. 3). University of Missouri students have saved $5.2 million through its AutoAccess program, and each student enrolled in an AutoAccess class saves an average of $68.13 per course, according to the Mizzou Store (2017, 0:23).

Growth of inclusive access has been greater at independent—rather than leased—college stores, said Mike Hale of VitalSource and Tim Haitaian of RedShelf (as cited in McKenzie, 2017, The Role of Campus Stores section, para. 5). According to the National Association of College Stores, 23% of independent college stores had inclusive access programs in place for 2017–18 and another 32% said they were considering adopting a program (as cited in McKenzie, 2017, The Role of Campus Stores section, para. 4). Inclusive access is also expanding at leased stores operated by Barnes & Noble College and Follett. Patrick Maloney of Barnes & Noble College said the number of campuses using its First Day program doubled in the past year (as cited in McKenzie, 2017, The Role of Campus Stores section, para. 5).

Major education publishers are engaged in inclusive access as well. Representatives from Cengage, Macmillan Learning, McGraw-Hill Education, Pearson, SAGE Publishing, and Wiley all attended the first-ever Inclusive Access Conference in 2017, sharing information about their various models.

Evolution of Inclusive Access

The evolution of the inclusive access model can be attributed to a number of factors. In a blog post on publisher Wiley’s website, Ruel (2017) said that the model evolved from a combination of “regulatory change, publishing technology, and extensive collaboration” (Why Now? section, para. 1). According to Wheeler, other factors in the model’s growth include maturation of the smartphone and tablet markets, and a growing sense that faculty and students are now more comfortable with digital course materials (as cited in Straumsheim, 2016, para. 6). As K–12 schools and entire school districts (like the Vail School District near the University of Arizona) switch from print to all-digital course materials, more students will enter college expecting online access.

“Technology has given students new ways to obtain information,” said Straumsheim (2017). “The rental and used book markets have cut into publishers’ bottom lines. Open educational resource providers have sprung up to offer free or affordable alternatives to traditional textbooks” (para. 3). “Publishers have been forced to reassess their business model,” said the Student Public Interest Research Groups (PIRGs). “Raising costs to make up for lost revenue has only furthered the problem, causing more students to opt out of purchasing books entirely” (2016a, p. 9). In a 2016 survey of more than 22,000 students from Florida’s public colleges and universities, 66.6% reported not purchasing a required textbook, up from 63.6% in 2012 (Florida Virtual Campus, 2016, p. 10).

Pearson’s Tim Peyton said it was no secret that publishers like Pearson had made textbooks too expensive and had seen sales drop as a result (as cited in McKenzie, 2017, para. 2). Market pressures on textbook publishers have been evident in financial results. Pearson, the world’s largest book publisher, posted a 15% decline in sales in 2016 (Milliot, 2017, para. 1). Revenue also declined in 2016 for McGraw-Hill Education, Wiley, Cengage Learning, and Macmillan parent company Holtzbrinck (Milliot, 2017, rankings chart). In January, 2017, Pearson’s stock price took a record tumble, and Chief Executive Officer John Fallon said one of Pearson’s plans for boosting its digital revenue in the U.S. higher education division—Pearson’s biggest and most profitable—involved “working with more institutions to sign up large blocks of students” [inclusive access] (as cited in Penty & Heiskanen, 2017, para. 2 & 11).

Regulatory Change

While various forms of inclusive access existed before 2015, McKenzie said “the inclusive-access explosion appears to have been precipitated by a 2015 Department of Education regulation, which enabled institutions to include books and supplies in their tuition or fees” (2017, A Win for Publishers, Discounts for Students section, para. 1). The rules went into effect July 1, 2016. According to the regulation, the cost of books and supplies can be included as part of students’ tuition and fees under three different scenarios (Berkes, 2015):

- If the institution has an arrangement with a book publisher or other entity that enables it to make those books or supplies available to students below competitive market rates, provides a way for a student to obtain those books and supplies by the seventh day of a payment period, and has a policy under which the student may opt out of the way the institution provides for the student to obtain books and supplies.

- If the institution documents on a current basis that the books or supplies, including digital or electronic course materials, are not available elsewhere or accessible by students enrolled in that program from sources other than those provided or authorized by the institution.

- If the institution demonstrates there is a compelling health or safety reason. (U.S. Government Publishing Office [GPO], 2016, §668.164[c][2])

In the first scenario, the opt-out requirement is a minimum. Some programs use opt-in instead. In Florida, state statute requires an opt-in provision for programs like inclusive access (Florida Legislature, 2017, section 5). The campus store at California State University, Fullerton, decided to have students opt in rather than opt out so that the store could offer the program to students even when there was not faculty buy-in (Angelo, 2018, p. 24).

Benefits of Inclusive Access

The potential benefits of inclusive access for students, faculty, publishers, campus stores, and academic units are varied. For students, for example, there can be dual financial benefits: potential cost savings and the ability to use financial aid to pay for course materials. At the UA, inclusive access content is charged to students’ Bursar accounts (unless they opt out) and students can then cover the cost with financial aid. Previously, when required to purchase a textbook directly from a publisher website (outside inclusive access), students needed to pay with a credit or debit card, which some do not have. When buying required course materials through the UA BookStores, students also save 6.1% on sales tax.

The potential benefits of inclusive access for students, faculty, publishers, campus stores, and academic units are varied. For students, for example, there can be dual financial benefits: potential cost savings and the ability to use financial aid to pay for course materials.

Inclusive access can offer other benefits to students as well, including time savings. As the parent of two college students, I have seen my own children expend time and energy comparison-shopping for lower prices (occasionally ending up with the wrong books or waiting weeks for mailed shipments). Some platforms, like those from VitalSource and RedShelf, have built-in annotation tools for highlighting and adding notes. Inclusive access materials may also include adaptive learning technology with personalized, interactive tools.

According to the Association of American Publishers (2016), multiple studies from education publishers have found that digital course materials result in better grades, higher retention rates, and improved learning. In research done by San Diego State University (SDSU)’s Social Science Research Lab, most surveyed students felt that participating in the Immediate Access Program benefited them academically, creating greater understanding of the material, higher engagement, and better preparation for tests and quizzes (Erhorn et al., 2017, slide 37).

For faculty, day-one access means that they can assign readings and homework from the first day of class, without waiting days or weeks for students to acquire the course materials (or waffling about whether to buy them at all). UA Professor Bill Neumann believes day-one access helps with student retention (personal communication, August 28, 2017). First-day access is especially important on campuses that use the quarter system or with courses that run just a few weeks. Every student has equal access at the beginning and the class can get off to a faster start.

Other benefits for faculty can include homework tools and learning analytics. Inclusive access products that provide test banks or do auto-grading can be time savers for busy faculty. According to RedShelf (n.d.), faculty can use RedShelf Analytics to see how students interact with ebook content, gain insight on learner engagement, and help identify at-risk students (Affordable. Accessible. Achievable. section). We have not surveyed UA faculty to see if they are using the learning analytics or find them useful. This data collection can be a double-edged sword, as I discuss in a later section.

For publishers, the appeal of inclusive access is economic.

For publishers, the appeal of inclusive access is economic. “For publishers with struggling print businesses, the inclusive-access model is a lifeline,” said McKenzie (2017, para. 2). In contrast to textbook rentals or sales of used textbooks, publishers earn money on every sale of inclusive access content. With low opt-out rates, revenue streams from inclusive access are likely to be more predictable. “Education publishers invest tremendous resources into the creation of textbooks,” said Hale (as cited in Dimeo, 2017, Michael Hale section, para. 3). It is estimated to cost an average of $750,000 to create the master copy of a college textbook, according to Esposito (2012, para. 7). Once publishers create a textbook, however, digital reproduction costs are minimal compared to those for printing.

For campus stores, the financial benefits of inclusive access programs include higher sell-through rates and lower overhead. Unlike print textbooks, the digital inclusive access content does not need to shipped, warehoused, shelved, or returned to publishers if unsold. No square footage is required for display or storage, allowing the store to use space differently for new products or services. Labor expenses from receiving, unpacking shipments, stocking shelves, and boxing up returns are now reallocated to managing the inclusive access program and other new services. Given the low opt-out rates, revenues from inclusive access courses are more predictable. “My opt-out rate is below 2%, so I know within 2% what my revenue for a course will be based on enrollment, and I have a pretty good idea what the enrollment is going to be,” said Scott Broadbent of Western Kentucky University’s campus store (as cited in Angelo, 2018, p. 27).

For programs or degrees with a single “all-inclusive” cost, inclusive access can be advantageous. At the UA, the Eller College of Management has become a wide adopter of inclusive access. Programs such as Eller’s Evening MBA and Online MBA, which provide all ebooks and course materials to students as part of the total program cost, use only inclusive access, saving the college money.

Concerns about Inclusive Access

Because of the newness of inclusive access programs on many campuses, the unfamiliarity to first-time users, and the complexity of integration with vendors, publishers, university systems, and LMSs, there are bound to be bumps in the road for the inclusive access model. At the UA, we have encountered technical difficulties, some user confusion, and the need for a great deal of manual work.

Technical Difficulties

In a survey done at SDSU, 11% of students reported technical issues with the Immediate Access Program (Erhorn et al., 2017, slide 32). The UA has experienced a number of glitches with inclusive access, particularly when using a publisher for the first time. Unbeknownst to the UA BookStores, faculty, or students, for example, several publishers required students to click on the ebook during the free-access period in order to activate the content. If students did not opt out but also did not open the content by the opt-out date, they lost access even though they had been charged. (Some students discovered this the night before a midterm.) Access had to be manually activated by UA staff.

On one publisher’s website, students were prompted to buy the ebook directly from the site. Students who did so but did not opt out of inclusive access got billed for the course’s inclusive access version as well. The publisher’s price was higher than the inclusive access price, so the UA BookStores helped students obtain refunds from the publisher, and we now ask publishers to remove website prompts for direct sales to students.

Individual access codes for students also were a logistical headache. They sometimes resulted in delayed access for students, and took a great deal of staff time to resolve, so the UA BookStores now request no codes or a single class code. “Ultimately, we are looking for the best experience for the students, and so the least complicated way to access the content the better,” said BookStores’ Assistant Director Cindy Hawk (personal communication, July 3, 2018).

For campus store personnel, LMS support staff, and instructors or program managers who deal with multiple course sites, setting up, managing, and troubleshooting inclusive access can be an extensive and time-consuming process.

For campus store personnel, LMS support staff, and instructors or program managers who deal with multiple course sites, setting up, managing, and troubleshooting inclusive access can be an extensive and time-consuming process. Instructors, program managers, or instructional designers need to take action in the course site to set up the inclusive access links. This crucial step is difficult to automate at the UA. In at least one course, it was discovered about three weeks into the class that the link had not been set up properly in our LMS, so students had been unable to access the ebook. As inclusive access programs scale up at institutions, this could be an increasing challenge—it is one thing to monitor a few course sites, but quite another to check on hundreds or thousands.

The accessibility of digital content for people with disabilities may also be a concern, depending upon platform features and compatibility with adaptive technology such as screenreaders or text-to-speech software. Accessibility issues are not unique to inclusive access, however (see This Chapter for more details).

Potential Confusion

With inclusive access still fairly new at the UA, the term remains unfamiliar to some students and faculty. Students have come to the UA BookStores looking for the textbook Inclusive Access, confusing the program’s name with the title of an assigned book.

With multiple vendors and publishers in use at the UA, students must learn to navigate a variety of different proprietary systems and platforms. Post-class access to content (if allowed) may be confusing as well. At the UA, students lose access to course sites after the first month of the next major semester (e.g., in February for Fall/Winter courses). If student access to inclusive access content has been negotiated to last longer than one term, but the class has ended, students need to remember the platform or publisher website on which the ebook can be found and how to get there. They may need to create an account on the other system (or remember the account they created). Verba uses publisher websites, while with RedShelf it depends whether instructors are using an ebook alone or an ebook plus homework system. If there is only an ebook, the RedShelf platform is used; with an ebook plus homework, both the RedShelf platform and publisher website are used. So while publishers/vendors may technically allow extended use of inclusive access content, access complexities may prevent students from even trying.

At the UA, ebook linking also varies by vendor. Verba uses the publishers’ technologies as the means of integration, and direct linking to chapters is possible. In RedShelf and VitalSource, linking takes students to the entire ebook. This has frustrated some faculty accustomed to organizing weekly readings by chapter. RedShelf does offer a hybrid solution, but it involves adding RedShelf and publisher links to the course site. These variations in linking lead to an inconsistent user experience for both faculty and students, which is not optimal for teaching or learning.

Opt-Out Challenges

A variety of opt-out challenges exist when implementing an inclusive access model. Although Department of Education regulations usually require the ability to opt out of inclusive access, opting out may make it impossible to succeed in a course. If a digital courseware package is the only way to complete assignments or take exams, students really have no choice but to buy it. Another issue at the UA is that opt-out periods vary, depending on course length. In a UA winter session course that only lasts a few weeks, for instance, students get just three days to opt out.

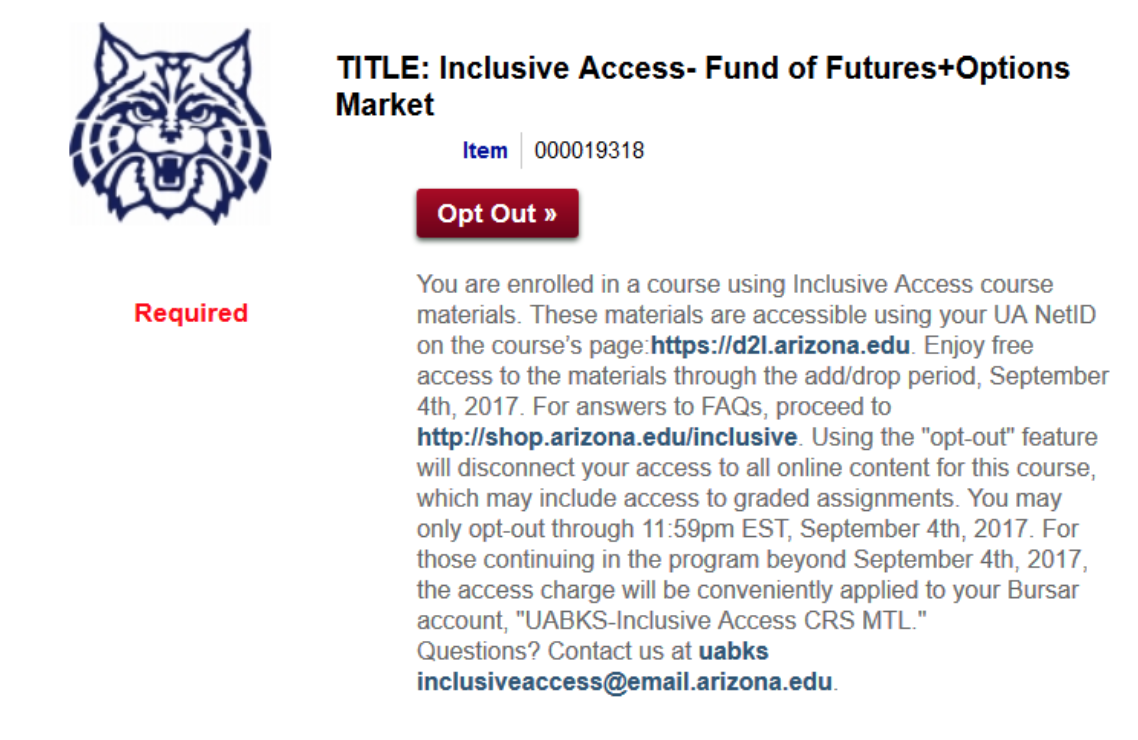

Adding to administrative complexity, opt-out functions work differently, depending upon the platform. With Verba and VitalSource, the opt-out integrates with the UA’s PeopleSoft system. With RedShelf, the opt-out is through Learning Tools Interoperability (LTI) in D2L Brightspace. This means that UA students face different processes for opting out of inclusive access. With content from Verba and VitalSource, the opt-out button is located in the UA BookStores’ textbook portal for students (see Figure 2); it’s not available in our LMS, where students primarily work and access the provided content. For RedShelf content, a different opt-out process is handled through the LMS.

The UA has a detailed handout for students on how to opt out of the various platforms, while the UA BookStores have set up an FAQ site with a dedicated email address for help. Faculty are urged to explain inclusive access on the first day of class and provide information in the syllabus. Students receive multiple email reminders about opt-out deadlines. During the pilot phases, the UA BookStores have been flexible with students who have changed their minds about opting in or out after the deadline, but as the program grows and matures there will be less flexibility.

Figure 2: View of a required inclusive access textbook from the UA BookStores’ textbook

portal for students.

Unless institutions make the opt-out process easy and clear, students who want to opt out may have difficulty doing so. Some institutions actively discourage students from opting out. Jhangiani (2017) noted that “at institutions like Post University the opt-out terms are more than restrictive; they are punitive” (para. 3). Post students who opt out “will not be eligible for an extension on course assignments while they await arrival of their course materials,” which they must buy elsewhere (Post University, 2017, para. 3).

Digital Divide

Most inclusive access models provide only digital content. If students prefer print, own a device that is not compatible with the vendor/publisher’s proprietary system, or have no device on which to read the online content, they must pay extra for a print version. Self-printing may be an option, but unless an institution has negotiated with publishers to allow students to print as many pages of the digital textbook as they want (as Indiana University does [Straumsheim, 2016, para. 23]), printing may be limited. Self-printing limits for inclusive access textbooks can vary by publisher and even by title. This is the case at the UA.

In a 2017 survey of provosts and chief academic officers by the Campus Computing Project, two-fifths of respondents said that campus efforts to go “more digital” or “all digital” were impeded because many students do not own the devices they need to access digital content (Green, 2017, p. 3). Inclusive access is meant to provide all students access to course materials from the first day of class, but this goal is not accomplished if students lack the necessary technology.

Unavailable or unreliable internet connectivity poses another challenge for students trying to use digital content. With VitalSource, ebooks can be downloaded and read offline if a student has the Bookshelf app (VitalSource, 2017b). Offline reading is also possible with RedShelf, but there may be limitations on the number of days and the percentage of the book that can be accessed offline (RedShelf, n.d., FAQ: How do I access Offline mode?).

Also of concern is a lack of perpetual access to inclusive access content. Time limits such as 180 days may be problematic for courses that span more than one term or for students who need the content to study for cumulative exams (e.g., to be a Certified Public Accountant).

Level of Cost Savings

Given that five major publishers control 80% of the textbook market, and that students are a captive market with zero choice about which textbooks are assigned to them (Student PIRGs, 2016b, p. 1), there are concerns that publishers (whose shareholders expect profits) will increase inclusive access prices once faculty and institutions are hooked on the model. At the 2017 Inclusive Access Conference, Tom Malek of Pearson Education said he believes publishers will start “competing like crazy” on inclusive access pricing and that OERs will be a stabilizing factor. Others are skeptical. “[The price] may be lower now, but there are no safeguards against prices skyrocketing all over again,” said Allen of SPARC (2017). A math professor at the UA told me that the price of inclusive access content in her course has steadily crept back up over three semesters; while savings are now minimal, she still considers the day-one access an advantage.

According to Department of Education regulations, publishers only need to offer inclusive access materials “below competitive market rates” (U.S. GPO, 2016, §668.164[c][2]). Jhangiani (2017) said inclusive access pricing “represents an arbitrary discount off the (arbitrary) price of a new hardcover textbook (often more than the average student currently spends)” (para. 3). Pricing is not transparent, and cost savings depend upon the negotiating skills of campus stores and/or faculty. While discounts on some titles have been substantial at the UA, and negotiating power may increase as more classes move to inclusive access, other discounts have been paltry. In the UA’s Fall 2016 pilot of inclusive access, one digital textbook was discounted a mere $2 by the publisher—a savings of 3%. The UA also has found that prices from the same publisher can vary, depending on which platform is used.

Faculty may be unaware that they can negotiate on pricing with publishers, or may be reluctant to do so. This is not the case with UA Professor Neumann, who leverages a large class size and multiple textbook choices “like a 500-pound gorilla” when negotiating pricing with publishers (personal communication, August 28, 2017). Neumann teaches MIS 111, the biggest class on campus. With about 1,500 students each semester, he tells a publisher “this is the price I want”—if a publisher is unwilling to go low enough, Neumann has three or four other textbook options to pursue (personal communication, August 28, 2017). Faculty “have to be willing to walk away from publishers,” Neumann emphasized (personal communication, August 28, 2017).

Concerns about Data Collection

While publishers and vendors tout the benefits of inclusive access’s analytics in terms of enhancing student learning, the practices surrounding this data collection raise a variety of concerns about information ownership, control, security, and usage. In librarianship, protecting user privacy and confidentiality is a core value (American Library Association, 2004, para. 4). The federal Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) also protects the privacy of student education records.

While publishers and vendors tout the benefits of inclusive access’s analytics in terms of enhancing student learning, the practices surrounding this data collection raise a variety of concerns about information ownership, control, security, and usage.

At the 2017 Inclusive Access Conference, RedShelf co-founder and Chief Executive Officer Greg Fenton said, “We can tell you everything to a super creepy level” about student usage of inclusive access materials with the platform’s built-in analytics. At a 2017 EDUCAUSE session titled “The Wicked Problem of Learning Data Privacy,” Jim Williamson of the University of California at Los Angeles said that learning analytics may be “well-meaning” but they also pose challenges: “What happens when students get stereotyped [based on their data] and how do you handle outliers?” (as cited in Johnson, 2017, para. 10–13). In her Hack Education blog, Audrey Watters (2017) cited a range of data concerns with educational analytics: discriminatory tendencies in algorithmic decision-making, possible “weaponization” of data against students (regarding immigration status, for instance), data insecurity and breaches, and questions about the systems’ accuracy and effectiveness. “There are major ethical implications of these sorts of analytics in education,” said Watters (2017, Algorithmic Discrimination section, para. 3).

According to Billy Meinke, an OER Technologist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, vendors’ and publishers’ end-user license agreements (EULAs) for inclusive access need to be far more transparent (2018a, 2018b). On behalf of their students, institutions need to hold publishers and vendors accountable and ask: Who owns the resulting data from students’ use of inclusive access content—the publisher/vendor or the institution? Which personnel on campus have access to the data (faculty? advisors? the campus store?) and for how long does this access last? Where will student data be stored? How will data security be ensured? How will data and analytics be used by publishers and vendors? Can data be sold to a third party? “These are our students, and we need to ensure that publishers are not putting their personal information at risk,” Meinke asserted (2018b, para. 7).

Dangers of Reliance upon a Single Vendor

There are a number of reasons to avoid relying upon a single provider for content—academic freedom, the right of faculty to select course materials (Franke, n.d., p. 3), and the fact that a lack of competition could result in higher prices. “Limiting faculty to one particular publisher or conglomerate of publishers is certainly an issue,” said Jhangiani (as cited in McKenzie, 2017, Unrestricted Choices section, para. 1). Faculty (or academic units, in the case of multi-section classes that adopt the same textbook) should be able to choose the best course materials to meet class learning objectives, regardless of publisher.

Another risk with using a single vendor is that the company could suddenly go out of business. This happened in 2016 when a startup company called Rafter, which offered an “all-inclusive materials solution” for print and digital textbooks, abruptly shut down (Young, 2016). More than a dozen small colleges that had been using Rafter’s service were left scrambling to find an alternative (Blumenstyk, 2016, para. 1). Officials at Avila University received just two days’ notice that Rafter was ceasing operations (Young, 2016, para. 13).

Recommended Best Practices

After piloting inclusive access for three semesters at the UA, BookStores’ Assistant Director Hawk said, “We (along with the publishers, and faculty) are still learning a lot, and are working to streamline the process better so it’s more scalable. At the moment, there is still a lot of manual work on all parts of the program, as well as small technological bumps” (personal communication, October 6, 2017). When setting up an inclusive access program, Hawk and Debby Shively, Assistant Vice President of Entrepreneurial Services, recommend:

- Addressing the challenges outlined in this chapter.

- Targeting courses that:

- Have high enrollments (for higher impact and more leverage in price negotiations).

- Are offered online (so students have instant access to the course materials).

- Require textbooks and use them extensively throughout the term (required textbooks that courses never use = angry students).

- Use expensive textbooks with low sell-through.

- Use adaptive learning technology such as Connect, MindTap, or ALEKS (inclusive access offers better pricing).

Having faculty actively engage students with inclusive access content during the free-access period (for best opt-out decision-making).

Clearly and repeatedly explaining inclusive access to students, and sending multiple reminders about opt-out deadlines and procedures.

Other Considerations

In its brochure “Inclusive Access: Your Ticket to Unstoppable,” Cengage (n.d.) advised institutions also to consider:

- State regulations around course fees [at the University of Arizona, the state Board of Regents must approve any new class fee above $100].

- How to get buy-in from leadership.

- Who can oversee the implementation and faculty training.

- Communication strategy for rolling out the model to students and instructors.

- Variety of materials requiring access.

- Campus technology capabilities.

- Process for overcoming obstacles.

- Methods for evaluating the results post-implementation. (p. 7)

Conclusion

This chapter has attempted to take a balanced look at inclusive access, its evolution and growth, and the model’s potential advantages and disadvantages. I agree with Temple Associate University Librarian Steven Bell (2017a, 2017b, 2017c) that, as part of the broad “textbook affordability spectrum,” inclusive access can be viewed as a step in the right direction. Cost savings and day-one access clearly benefit students. If free resources are unavailable, or if faculty prefer commercial publishers’ course materials, significantly discounted inclusive access content is preferable to having students pay higher prices or struggle (and possibly fail) to pass courses without the required materials.

Publishers benefit from the model’s low opt-out rates, sometimes-minimal pricing discounts, and collection of student data. I see possible advantages for students, faculty, and campus stores as well. I do have reservations about the model’s long-term pricing, short access periods, use of proprietary systems, and the impact of any technological glitches upon faculty instruction and student learning. I am also concerned that “opting out” of inclusive access may not be a viable option for students: If a digital courseware package is the only way to complete assignments or take exams, students really have no choice but to buy it.

Campus partners need to work collaboratively with vendors and publishers to improve inclusive access functionality and terms of use. With student success as a common goal, we can all join forces to make course materials more accessible and affordable.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to University of Arizona colleagues Mark Felix, Cindy Hawk, Bill Neumann, Valeria Pietz, and Debby Shively for providing campus inclusive access statistics and for sharing their perspectives and lessons learned.

References

Allen, N. [txtbks]. (2017, November 7). Publishers also set the price. It may be lower now, but there are no safeguards against prices skyrocketing all over again. [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/txtbks/status/928008876456337408

American Library Association. (2004, June 29). Core values of librarianship. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/corevalues

Angelo, D. (2018, March/April). Lessons learned: Campus stores share insights and tips from rolling out and growing inclusive-access programs for their schools. The College Store Magazine. Retrieved from http://onlinedigitalpublishing.com/publication/?i=479094#{%22issue_id%22:479094,%22page%22:24}

Association of American Publishers. (2016, September 28). Studies show college students get higher grades and learn better with digital course materials. Retrieved from http://newsroom.publishers.org/studies-show-college-students-get-higher-grades-and-learn-better-with-digital-course-materials

Bell, S. J. [StevenB]. (2017a, June 29). Message posted to http://thatpsychprof.com/just-how-inclusive-are-inclusive-access-programs/#comment-5754

Bell, S. J. [blendedlibrarian]. (2017b, November 7). Message posted to https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/11/07/inclusive-access-takes-model-college-textbook-sales

Bell, S. J. [blendedlib]. (2017c, November 7). What I meant by “textbook affordability spectrum” in my comment to this @insidehighered piece on “all inclusive access” learning content https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/11/07/inclusive-access-takes-model-college-textbook-sales … #OER #textbookaffordability [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/i/web/status/927963679500521473

Berkes, J. (2015, November 3). Final rules intended to further refine program integrity and improvement. Retrieved from https://www.nasfaa.org/news-item/6546/Final_Rules_Intended_to_Further_Refine_Program_Integrity_and_Improvement

Blumenstyk, G. (2016, October 7). Sudden demise of start-up textbook supplier leaves small colleges to scramble. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/Sudden-Demise-of-Start-Up/238025

Cengage. (n.d.). Inclusive access: Your ticket to unstoppable. Retrieved from https://www.cengage.com/institutional/inclusive-access#

Dimeo, J. (2017, April 19). Turning point for OER use? Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2017/04/19/new-yorks-decision-spend-8-million-oer-turning-point

Erhorn, S., Frazee, J., Summer, T., Pastor, M., Brown, K., & Cirina-Chiu, C. (2017, January). SDSU’s Immediate Access Program: Providing affordable solutions [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://www.csuaoa.org/conference/docs/2017/commercial_services/AOA_Presentation%20Slide%20Deck%20Immediate%20Access.pptx

Esposito, J. (2012, October 10). Why are college textbooks so expensive? [Blog post]. The Scholarly Kitchen. Retrieved from https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2012/10/10/why-are-college-textbooks-so-expensive

Esposito, J. (2017, March 27). How to reduce the cost of college textbooks [Blog post]. The Scholarly Kitchen. Retrieved from https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2017/03/27/reduce-cost-college-textbooks

Fenton, G. (2017, November 10). Inclusive: Where it’s come from and where is it going? Session presented at the Inclusive Access Conference, Atlanta, GA.

Florida Legislature. (2017). The 2017 Florida Statutes—Chapter 1004.085: Textbook and instructional materials affordability. Retrieved from http://leg.state.fl.us/STATUTES/index.cfm?App_mode=Display_Statute&Search_String=&URL=1000-1099/1004/Sections/1004.085.html

Florida Virtual Campus. (2016, October 7). 2016 student textbook and course materials survey. Retrieved from http://www.openaccesstextbooks.org/pdf/2016_Florida_Student_Textbook_Survey.pdf

Franke, A. (n.d.). Academic freedom primer. Retrieved from http://agb.org/sites/default/files/legacy/u1525/Academic%20Freedom%20Primer.pdf

Green, K. C. (2017, November). Provosts, pedagogy and digital learning: The 2017 ACAO survey of provosts and chief academic officers. Retrieved from http://www.acao.org/assets/caosurveysummary.pdf

Indiana University. (2017, April 6). Indiana University’s eText program saves students over $3.5 million. Retrieved from https://itnews.iu.edu/articles/2017/indiana-universitys-etext-program-saves-students-over-3.5-million.php

Jhangiani, R. (2017, June 29). Just how inclusive are ‘inclusive access’ e-textbook programs? [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://thatpsychprof.com/just-how-inclusive-are-inclusive-access-programs

Johnson, S. (2017, November 1). Invasive or informative? Educators discuss pros and cons of learning analytics. Retrieved from https://www.edsurge.com/news/2017-11-01-invasive-or-informative-educators-discuss-pros-and-cons-of-learning-analytics

Malek, T. (2017, November 10). Inclusive publisher panel. Session presented at the Inclusive Access Conference, Atlanta, GA.

McKenzie, L. (2017, November 7). ‘Inclusive access’ takes off. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/11/07/inclusive-access-takes-model-college-textbook-sales

Meinke, B. (2018a, March 22). Student data harvested by education publishers: They haz more than u think. Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@billymeinke/student-data-harvested-by-education-publishers-they-haz-more-than-u-think-4a952e0853de

Meinke, B. (2018b, March 27). Signing students up for surveillance: Textbook publisher terms of use for data. Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@billymeinke/signing-students-up-for-surveillance-textbook-publisher-terms-of-use-for-data-24514fb7dbe4

Milliot, J. (2017, August 25). The world’s 54 largest publishers, 2017. Publishers Weekly. Retrieved from https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/international/international-book-news/article/74505-the-world-s-50-largest-publishers-2017.html

Mizzou Store. (2017, September 22). Textbook affordability @ Mizzou [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CbU7I7fE23E

Penty, R., & Heiskanen, V. (2017, January 18). Pearson forecasts years of textbook gloom; to sell Penguin. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-01-18/pearson-withdraws-2018-profit-goal-will-exit-penguin-venture

Post University. (2017). Electronic course materials and ordering course materials through the online bookstore. Retrieved from http://post.edu/student-services/academic-affairs/academic-policies-and-procedures/ecm-and-textbook-ordering

RedShelf. (n.d.). Frequently asked questions. Retrieved from https://www.redshelf.com/faq

RedShelf. (n.d.). RedShelf Inclusive. Retrieved from https://www.redshelf.com/inclusive

Ruel, C. (2017, January 13). How inclusive access purchasing programs can lower the cost of higher education [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://hub.wiley.com/community/exchanges/educate/blog/2017/01/12/how-inclusive-access-purchasing-programs-can-lower-the-cost-of-higher-education-and-more

Ruth, D. (2017, November 16). OpenStax textbooks now available through bookstore digital access programs [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://openstax.org/blog/openstax-textbooks-now-available-through-bookstore-digital-access-programs

Straumsheim, C. (2016, September 16). Indiana’s grand textbook compromise. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/09/16/indiana-us-etexts-initiative-grows-textbook-model-emerges

Straumsheim, C. (2017, January 31). Is ‘inclusive access’ the future for publishers? Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/01/31/textbook-publishers-contemplate-inclusive-access-business-model-future

Student Public Interest Research Groups. (2016a). Access denied: The new face of the textbook monopoly. Retrieved from https://studentpirgs.org/sites/student/files/reports/Access%20Denied%20-%20Final%20Report.pdf

Student Public Interest Research Groups. (2016b). Covering the cost: Why we can no longer afford to ignore high textbook prices. Retrieved from https://studentpirgs.org/sites/student/files/reports/National%20-%20COVERING%20THE%20COST.pdf

University of Arizona BookStores. (2017). Buy UA, for UA. Retrieved from http://uabookstores.arizona.edu/wedomore/default.asp

U.S. Government Publishing Office. (2016, April 7). Electronic Code of Federal Regulations; Title 34: Education; §668.164. Retrieved from https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=f26563f69fbe76d894166903c246601c&mc=true&node=se34.3.668_1164&rgn=div8

VitalSource. (2017a, September 19). Study confirms costs lead students to forgo required learning materials; grades suffer as a result. Retrieved from https://press.vitalsource.com/study-confirms-costs-lead-students-to-forgo-required-learning-materials-grades-suffer-as-a-result

VitalSource. (2017b, October 26). How can you access your textbook? Retrieved from https://support.vitalsource.com/hc/en-us/articles/205852378-How-can-you-access-your-textbook-

Watters, A. (2017, 11 December). The weaponization of education data [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://2017trends.hackeducation.com/data.html

Wiley, D. (2017, November 8). If we talked about the internet like we talk about OER: The cost trap and inclusive access [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/5219

Young, J. R. (2016, October 14). Why Rafter failed, and what it means for edtech. EdSurge. Retrieved from https://www.edsurge.com/news/2016-10-14-why-rafter-failed-and-what-it-means-for-edtech

Author Bio:

Cheryl Cuillier joined the University of Arizona Libraries in 2009. As the Open Education Librarian, she oversees course material initiatives including OER, library-licensed ebooks, and streaming video. She also coordinates the OER Action Committee, manages web content, and serves on Faculty Senate. She has presented about OER at OpenEd and state conferences, is a member of the Open Textbook Network (OTN) Steering Committee, and is an OER Librarian Bootcamp instructor for the OTN. She received the 2016 Lois Olsrud Library Faculty Excellence Award at the UA Libraries.