Individual Courses

Chapter 2 – Accessing Science through an Online Database: A Comparison of Student Learning and Engagement Using Library Database Readings as a Textbook Alternative

Mary Ann Cullen, Dion Stewart, and C. Bayard Stringer

by Mary Ann Cullen, Dion Stewart, and C. Bayard Stringer (all from Georgia State University, Perimeter College) (bios)

Introduction

Online alternatives to traditional textbooks can lower educational costs for students and provide students access to the text on the first day of class. In many science disciplines, however, free, high quality, online textbooks are not readily available. This chapter explores the affordable content option of using online readings from a science reference database (AccessScience) to replace assigned textbook readings in freshman-level geology and astronomy classes, discusses the practical aspects of selecting and using a database as an introductory learning resource, and looks at the librarian’s role in the project.

Origin of the Project

This project came about when our librarian notified science faculty of a trial subscription to a science database, asking them to examine the database and provide feedback about adding it to the library’s subscription collection. The database consisted primarily of encyclopedia-like articles about science topics, with supplementary information including videos and news articles.

This project came about when our librarian notified science faculty of a trial subscription to a science database, asking them to examine the database and provide feedback about adding it to the library’s subscription collection … One geology instructor decided to use the database in lieu of his current textbook.

One geology instructor decided to use the database in lieu of his current textbook. He had found that students seemed bored with the text and frequently did not do the assigned readings, and that some did not purchase the textbook due to its high cost, even though he had approved the use of older and thus less expensive editions. Circulation data also showed that few students were using the textbook placed on course reserve in the library. An astronomy instructor noted students often searched Wikipedia for answers to their homework rather than referring to the assigned text, a practice leading to incorrect answers and an incomplete understanding of course material.

The instructors speculated that students might be more interested in online sources, especially if they resembled something familiar, like Wikipedia. Unlike Wikipedia, however, the database articles are written by experts in the fields of study, with their credentials clearly visible at the beginning of each article. The librarian was interested to see if exposure to a high-quality resource would encourage students to use the database for reference when not required to do so.

The study took place at Georgia Perimeter College, a public, two-year, Associate degree-granting institution with an open access mission, meaning that admission is not restricted based on standardized test scores or high school grade point average. While the school has a few professional programs, the majority of students major in core academic programs that allow them to transfer to a four-year program at another university or college in pursuit of a bachelor’s degree. The science classes in this study count toward the science requirements of this core curriculum; the classes’ concepts are standardized across the University System of Georgia to facilitate transfer of credit. It is worth noting that in the year following the study, Georgia Perimeter College became Perimeter College, a distinct college within Georgia State University, a large research institution.

We were often asked why the instructors wanted to use this particular database, rather than choosing articles from the library’s existing and extensive collection. The faculty involved in the project preferred to use one database because they wanted a single, consistent place for the students to look for information, and wanted as well to simplify their own searches for appropriate readings. Many of the articles in the library’s existing databases were not written with the purpose of introducing college freshmen to a subject; most are either too basic for college-level work, too advanced, or too specific for an introduction to the subject. The encyclopedia-style articles in the database, written with an academic tone, provided foundational knowledge for the subject at hand.

We were also asked why the instructors did not use an openly licensed textbook, many of which are available online as well as in print. In this case, the researchers were specifically interested in using the database as an alternative resource. The librarian in this study is an advocate for low-cost textbook alternatives and has frequently served as a resource for finding open educational resources (OERs) for different subjects. She has identified textbook alternatives for many classes by using search aids such as Merlot, OER Commons, and the Open Textbook Library, as well as materials available through OpenStax and Affordable Learning Georgia. At the time of this project, however, she could find no viable textbook alternatives for introductory college geology and astronomy. While there were some openly licensed educational materials, they were piecemeal rather than being a single default resource that would fully replace the textbook.

The first year of the database subscription was funded jointly by the library’s funds and a Perimeter College STEM Mini-grant, itself funded by the University System of Georgia STEM II Initiative, and we obtained Institutional Review Board permission for the study. With these technicalities out of the way, we began preparing for use of the database.

Literature Review

Reviewing the literature related to this project, we found that using library resources for all or part of a course’s assigned readings is neither new nor uncommon. Library subscriptions to electronic databases provide students and faculty access to articles, ebooks, and other materials. Typically, these databases require user authentication to access copyrighted materials off-campus, and are available from the first day of class. Most databases provide permalinks to articles, making it easy for faculty to link to electronic materials in the library’s collection. While database subscriptions are not free, costs are not directly billed to students, so content is “free to students.” Database resources are as readily accessible as online course packs, but avoid the time and expense of digitizing materials and obtaining usage rights for individual articles (Buczynski, 2008).

Jennifer Knievel (2003) describes a project for the University of Colorado’s freshman writing program in which librarians drew from the library’s online collection to create a set of readings centered on various themes. These readings supplemented or replaced the course’s print anthology, described as having “static content, rigid topic selections, and dated material,” (p. 71). While the curated electronic readings were effective as a learning resource, Knievel noted some drawbacks: the changing nature of electronic collections as items are withdrawn beyond the control of the librarians, the greater-than-expected time to select articles, and the challenges of keeping up with current topics. One noted benefit, however, was that students became accustomed to using library resources.

Ratto and Lynch (2012) explored the use of e-textbook content available through the Books 24×7 database as an alternative to a traditional textbook in an introductory marketing course. A common hurdle in using ebook content is that usage can be restricted to 1–3 concurrent users, but all texts in this study were available concurrently to an unlimited number of users. Students had the option to use the print textbook only, the e-textbook only, or a combination of the two. By the end of the semester, just 4% of the students reported using only the print text, with the remainder split between the e-text only (44%) and a combination of the two (43%). Instructors reported no significant difference between grades during this semester and the previous semester, which used only the print textbook. End-of-course surveys and interviews indicated that the majority of students were at least “somewhat likely” to take another course using e-texts.

The literature did show promise for positive outcomes in student learning and attitudes when using online library resources as a learning resource, but none of the studies we found used a single reference database in lieu of a textbook.

Methods

Preparation for the Semester

Both the geology and astronomy instructors structured their classes to include short weekly quizzes on the material covered that week. For this study, one question on each quiz covered content found only in the assigned readings and not duplicated in the lecture or other in-class activity. Questions were carefully selected so that the readings-based questions were answered in both the textbook and the comparable database assignments.

The instructors included an explanation of the project in their syllabi. Textbook assignments were given by providing page or chapter numbers, while database assignments were given using hyperlinks or specific search terms for locating material within the database. Because some articles were too lengthy and advanced for the course content, most database assignments included additional instructions about which portions of the articles to read, as shown in Figure 1.

The librarian on the project showed the the instructors how to provide direct links to the articles using the college’s proxy server, and arranged for an online training session with the database vendor. She also prepared information for the students about how to locate and use the database apart from having a hyperlink to the required reading. She included instructions on how to set up a cell phone or other mobile device so that students could easily access the database without having to enter login credentials each time. This information was included in the course syllabus as well as in a LibGuide. In addition, she attended the first meeting of the Geology class to provide a short demonstration and to establish herself as a contact person for questions or problems. She also alerted other librarians in the college about the project so they would be prepared to answer questions in person or by virtual reference.

On the first day of class, the project was explained to the students. Informed consent forms were signed by all but eight of the students. One student in the Geology database class declined to participate, and seven Astronomy students did not return their consent forms. With data from the students who did not have signed agreements omitted from the results, there were a total of 42 Geology students (22 in the database group and 20 in the textbook group) and 142 Astronomy students participating in the study. In the data analysis, student identities were masked by using a number to represent each individual student.

Research Design

The geology instructor had one Physical Geology (GEOL 1121) class use only readings in the database; a textbook was not assigned for this section. Another section was assigned readings on the same content in Earth: An Introduction to Physical Geology (Tarbuck, Lutgens, and Tasa, 2016), one of the top-selling textbooks at four-year institutions that have a geology major. Lectures, assignments, and exam questions were the same in both classes so that all students were exposed to the same knowledge, with only the delivery methods being different. This “between-subjects design,” comparing one group with another, allowed for students to have realistic experiences of purchasing a textbook or having the benefits of a free-to-the-student textbook alternative available on the first day of class. (In one instance, the database assignment was to watch two videos, but for the sake of simplicity, the question covering this content will still be considered a “readings” question.)

In the Geology classes, data were collected that allowed correlation of students’ performance on the readings questions with performance on quizzes and exams. Rather than using average correct response rates to compare the classes, correlations examined whether students did as well on the readings questions as on the quizzes and exams; in other words, did each student do “as well as could be expected?” These correlations were compared for the two conditions to see if the database condition was more or less predictive of overall outcome than the textbook condition.

A different design was used in the Astronomy classes. The instructor used both the textbook and the database in two sections of ASTR 1010 (Astronomy of the Solar System) and two sections of ASTR 1020 (Stellar and Galactic Astronomy). In two sections, textbook readings from Astronomy Today (Chaisson & McMillan, 2014) were assigned during even-numbered weeks, while database readings were assigned during odd-numbered weeks; in the other two sections, the reverse was true. This “within-subjects design,” comparing performance of the same students in both experimental conditions, allowed for variations among students and in other extraneous variables such as time of day, holiday patterns, differences in lectures, etc. Students also had the opportunity to experience both the traditional textbook and the online database, so they could compare the two sources for themselves. (These classes also included some YouTube videos; these results are included separately from the database and textbook results but the related quiz questions are still referred to as “readings” questions.)

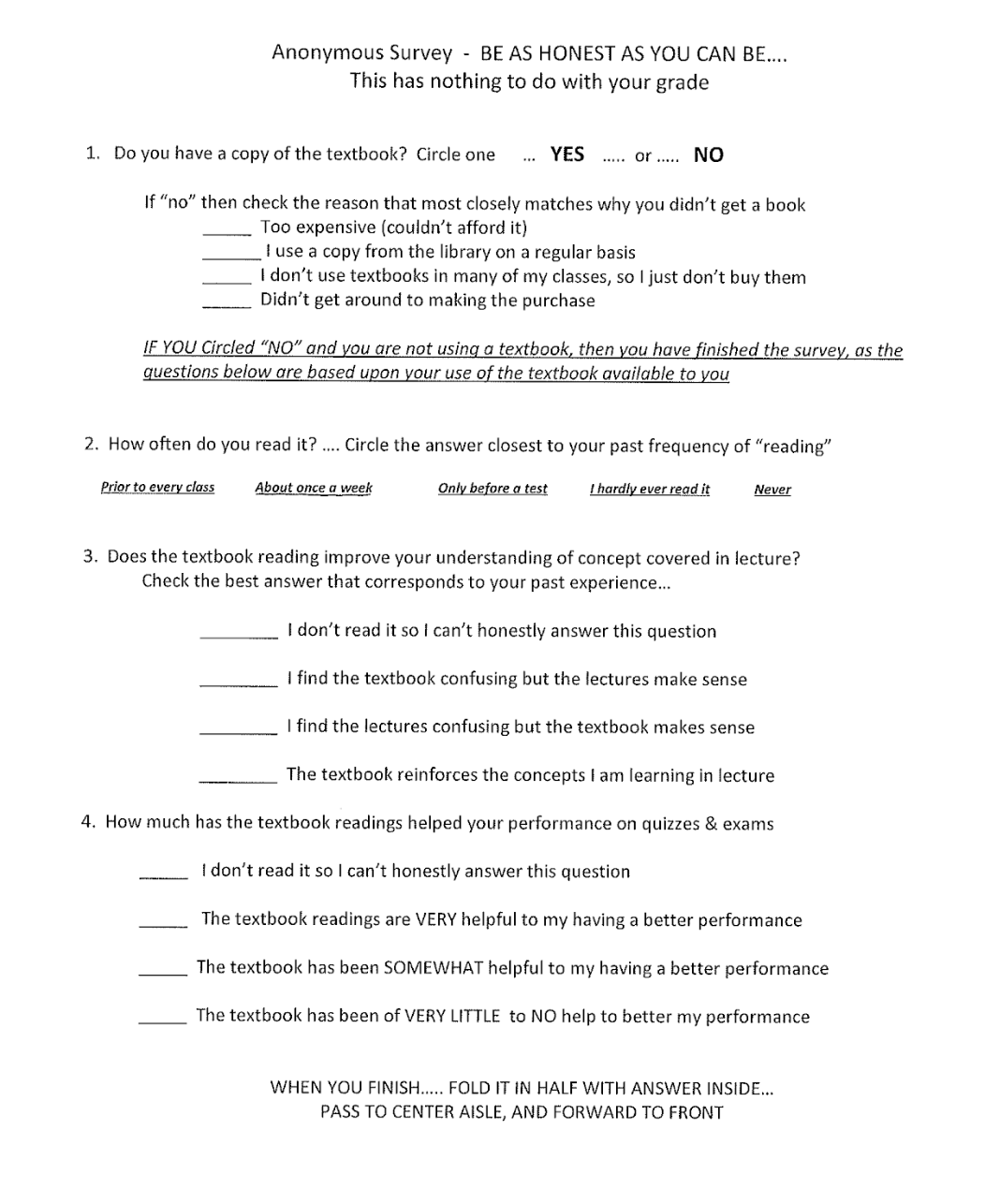

Student Impressions Survey

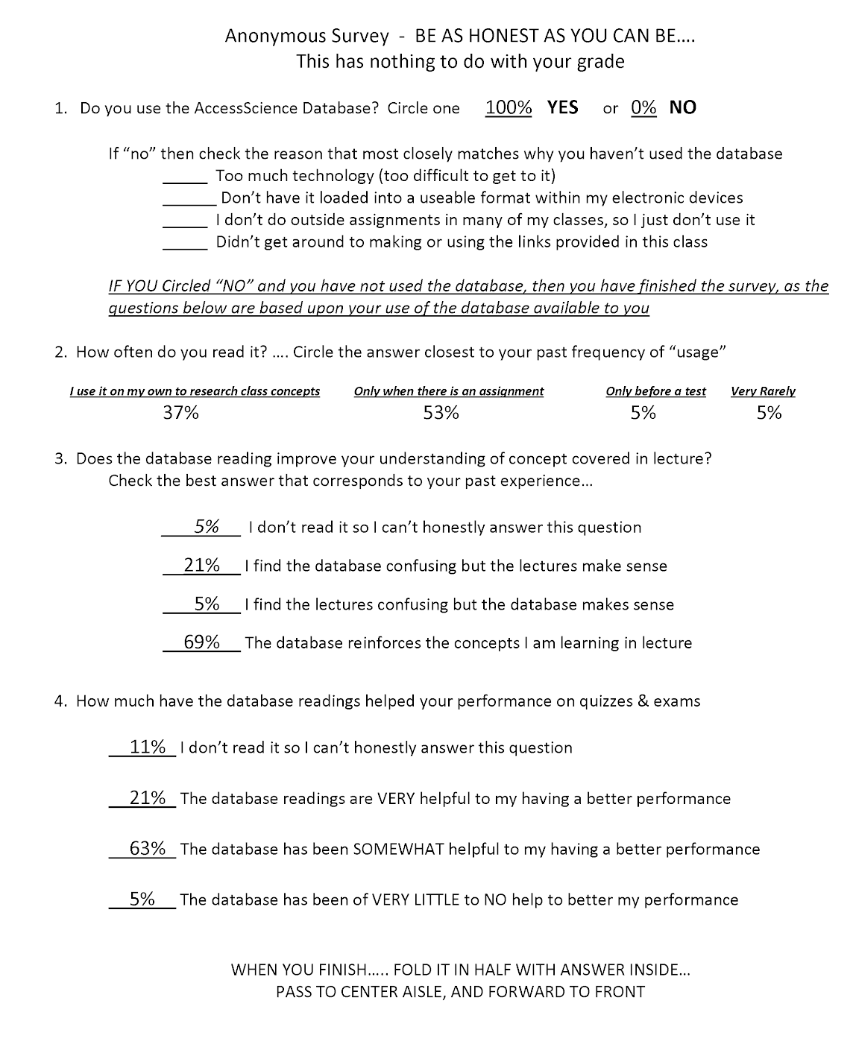

Geology classes also included an anonymous survey completed by students at the end of the course, asking if they used the assigned resource (textbook or database), how they used it, whether they felt the readings improved their understanding of the concepts presented in class lectures, and whether they felt the readings improved their class performance. Figure 2 shows an image of the survey given to the students using the textbook. The corresponding survey for the students using the database is provided in Figure 7 in the Results section.

Results

Geology Classes

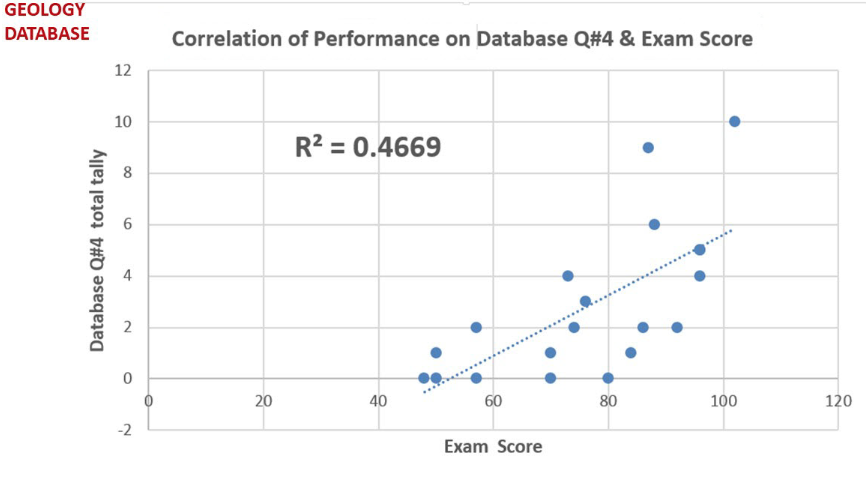

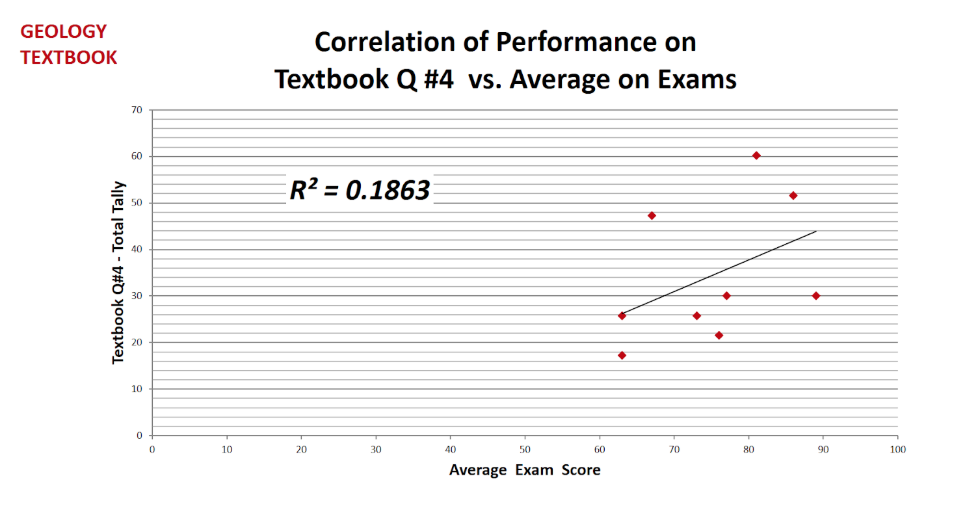

In the Geology classes, correlations of student scores for the readings quiz question (Q#4) with exam scores were calculated for both classes. For students in the class using the database (n=21), there was a moderately significant correlation (R2) of 0.4669 (Fig. 3). For students in the class using the textbook (n=20), the correlation (R2) was 0.1863, indicating there was not a significant correlation between performance on the readings quiz questions and performance on exam scores (Fig. 4). (Note: In the graphs, some data points represent more than one student.)

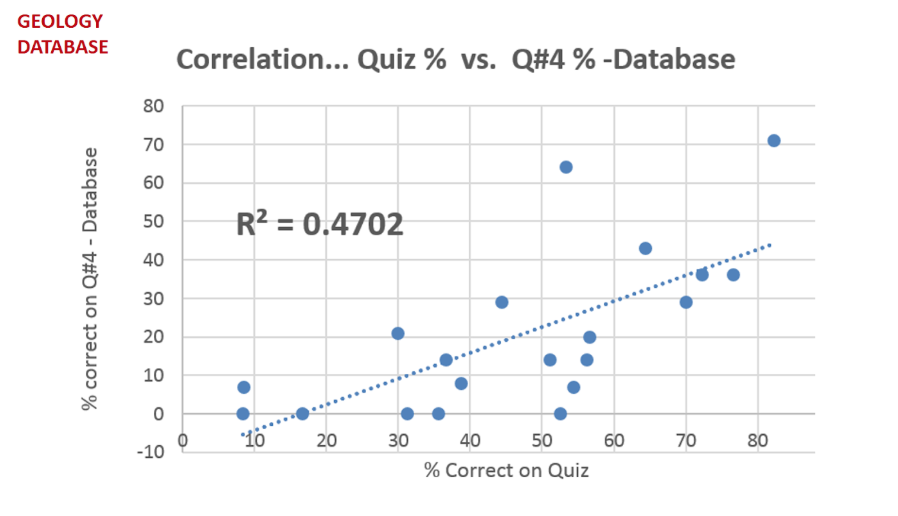

Correlations were also calculated comparing performance on the readings quiz questions (Q#4) and overall quiz performance. In the class using the database (n=21), there was a moderately strong correlation (R2) of 0.4702 (Fig. 5). For the class using the textbook (n=20), there was a correlation (R2) of 0.0491, indicating no significant relationship (Fig. 6).

Results on the surveys for the two classes were also compared (Figs. 7 and 8). Figure 7 shows the complete survey for the databases classes with the percentage of students who indicated each response. All students indicated in Question 1 that they used the assigned database, despite 5% and 11% of students in the database class subsequently responding to survey Questions 3 and 4, respectively, that they didn’t read the database assignments. Survey Question 2 asked students how they used the database. Fifty-three percent used it only for assigned class readings, but 37% reported “using the database on their own to explore class concepts.”

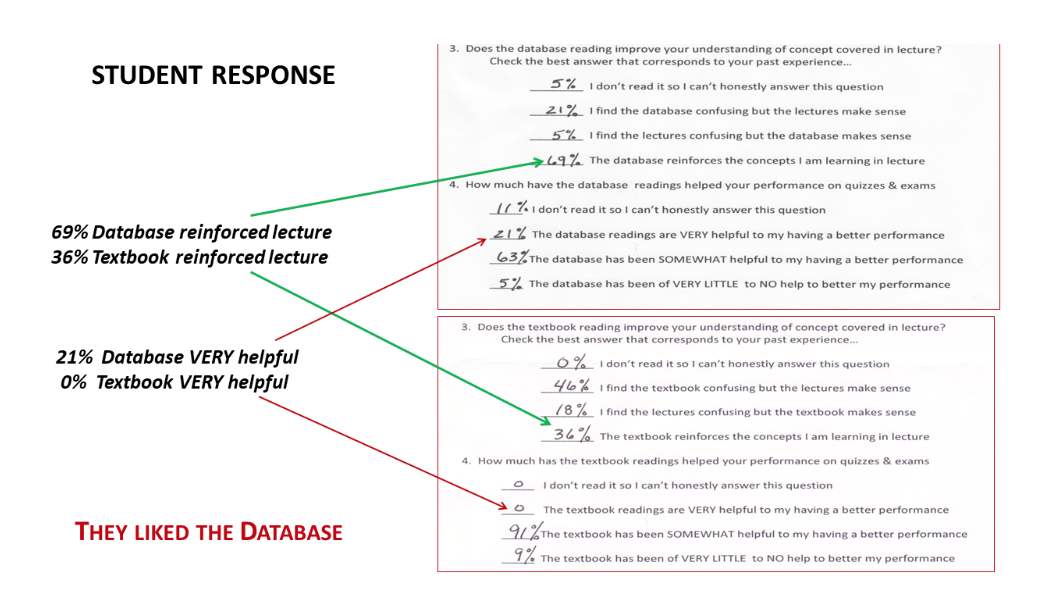

Figure 8 shows the comparison of each class’s responses to Questions 3 and 4. For Question 3, “Does the database/ textbook reading improve your understanding of concepts in the lecture,” 69% of students said the database reinforced concepts learned in the lecture while only 36% said the same of the textbook. For the Question 3 option, “I find database/textbook confusing, but the lectures make sense,” 21% found the database confusing while 46% said the same of the textbook. For Question 4, fewer than 10% of students in both classes found the readings “very little or no help” in bettering their performance on quizzes and exams. The biggest contrast was that 21% of students in the database group found the database “very helpful” while no students said the same of the textbook.

Astronomy Classes

Because all students in Astronomy classes were given assignments in both the database and the textbook, the within-subjects experimental design allowed for extraneous differences between classes. Indeed, measures for these classes were inconsistent between classes.

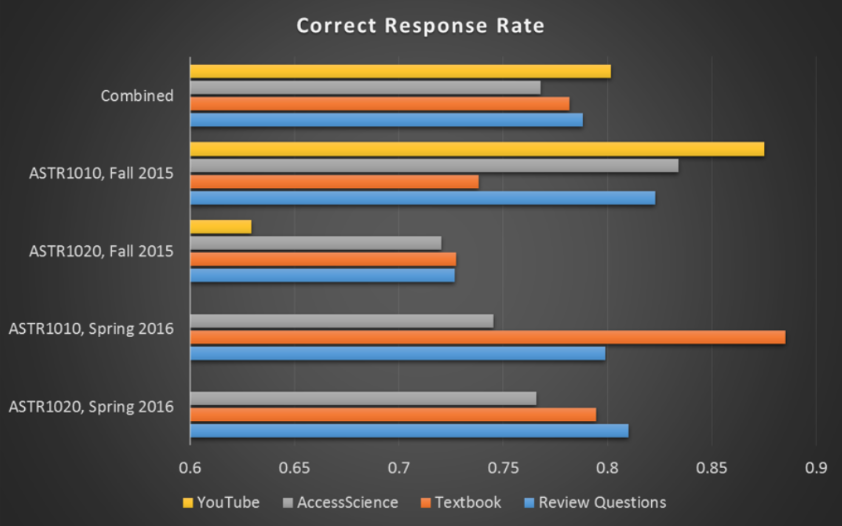

Figure 9 shows the rates of correct responses for all classes, as well as the combined results for all classes, for textbook questions, database questions, YouTube questions, and other review questions. (For clarity, the range shown in the graph is 60% to 90%.) The success rate for YouTube videos varied widely between classes, and there was no consistent pattern in textbook and database response rates. In one ASTR1010 class, the database questions were answered correctly more often than the textbook questions (83% vs. 74%), while the opposite was true in the other section of the same class (84% database vs. 88% textbook). In ASTR1020, the database and textbook questions were answered correctly at a roughly equal rate.

Comparison of the readings questions with performance on the review questions also varied from class to class. Using a Chi-square test, X2=1.12 with P=0.29. Using a critical value of Pα>0.05, the data do not support the hypothesis that any of the observed differences are statistically significant; they could be due to chance. Indeed, a qualitative inspection of the results does not indicate any obvious trends.

While no user feedback survey was given in the Astronomy classes, the instructor noted that much of the database content was above the course level and that students complained about the scholarly style of writing.

Conclusions

Survey results in the Geology classes indicated that students using the database found the assigned readings more helpful in supplementing the lecture than did students using the textbook. Likewise, compared to students using the textbook, more students using the database rated the readings as being “very helpful” in improving class performance. Correlations with the readings questions for these classes supported these statements, as there was a moderately significant correlation between performance on the database readings questions and average quiz and exam scores. In contrast, correlations between the readings questions for students using the textbook found no significant correlation between performance on these questions and performance on quizzes and exams. While the sample size was small, results indicate that the students rated the database more positively than the textbook and found it more useful for learning course material.

Results from the Astronomy classes showed no significant differences in class performance between the textbook and database conditions, indicating that the database could be as good at helping students learn course content as a traditional textbook, but at a lower cost.

In response to the librarian’s question of whether students would learn to use the database as a resource, the fact that 37% reported using the database to understand concepts even when not assigned is encouraging. Although it is doubtful that students would use the database if it was presented to them in class as a stand-alone potential resource, no definite conclusion can be drawn since students using the textbook were not surveyed about their use of the database. Anecdotally, the Geology instructor had six students from the database class in a subsequent course, and four reported that they continued to use AccessScience for other courses. Future studies could formally examine generalized use of the database by surveying students in the database groups to ask if they used the database beyond the assigned readings and if they continued to use it in other courses.

While using a reference database in lieu of a textbook can be an effective and low-cost-to-student alternative, we did encounter problems with the practical aspects.

While using a reference database in lieu of a textbook can be an effective and low-cost-to-student alternative, we did encounter problems with the practical aspects. The primary hurdle was the considerable amount of time it took for the instructors to find appropriate content in the database and communicate the assignments to students. Textbooks are written with a particular level of students and learning outcomes in mind, while a database is not. It is relatively easy to assign a specific textbook selection to cover certain material, but assignments of similar material in the database may require multiple articles, and when only portions of these articles are relevant to the current assignment, instructors will have to take the time to direct students to the relevant portions. In addition, while the database has no direct cost to students, the subscription cost comes out of the library’s budget or must be otherwise funded. When deciding whether to continue the subscription, the usual criteria of cost versus use and need apply; if the database is only used by a handful of students, it may not be the most effective way of providing a textbook alternative.

The instructors felt that the burden of finding appropriate readings could be greatly reduced if the adoption of a database was shared across all sections of the college. With the involvement of more faculty from the curriculum committee, a standard set of readings could be established that would be assigned in every section. This idea was explored with all science faculty at a “Development Conference” presentation, and while the response was moderately positive, the idea was not adopted.

Since the time of the study, both instructors have abandoned the use of the database as a textbook alternative, but both refer their students to it as a supplementary resource. Several reasons contributed to this decision. The Astronomy instructor found the assignments cumbersome, and students complained about the scholarly writing style. The Geology instructor encountered departmental mandates about standardized texts, and also found that the amount of time to select readings prohibited the expansion of this idea into other courses.

As the movement toward affordable textbook alternatives grows, an increasing number of subjects are covered by openly licensed and low-cost textbooks, including introductory college-level geology and astronomy courses. If an objective is to provide students with high-quality supplementary material, a reference database or carefully selected web resources could be assigned as additional readings or recommended to students as alternatives to less-authoritative websites. Librarians can help identify and assemble these resources in science guides or widgets for use in learning management systems.

The results of this study are limited in scope to the specific textbooks and database used. While results are encouraging in terms of the efficacy of the database to support student learning, additional study is needed to determine if these results are generally true. Instructors wishing to use a database in lieu of a text should be prepared for the initial time investment in setting up the readings. They should also consider issues with the library’s commitment to continuing the database subscription and departmental buy-in for using the database as a textbook alternative.

References

Buczynski, J. (2007). Faculty begin to replace textbooks with “freely” accessible online resources. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 11(4), 169–179.

Chaisson, E., & McMillan, S. (2014). Astronomy today (8th ed.) Boston: Pearson.

Knievel, J. E. (2003). Library databases as writing-course anthologies: Implications of a new kind of online textbook. Public Services Quarterly, 1(4), 67.

Ratto, B. G., & Lynch, A. (2012). The embedded textbook: Collaborating with faculty to employ library subscription e-books as core course text. Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship, 24(1), 1-16.

Tarbuck, E. J., Lutgens, F. K., & Tasa, D. (2016). Earth: An introduction to physical geology (12th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Author Bios:

Mary Ann Cullen is Associate Department Head at Georgia State University Library’s Alpharetta Campus location. Recipient of the Affordable Learning Georgia Textbook Transformation Award, she is an advocate for the use of textbook alternatives and the inclusion of librarians in textbook alternative projects.

Dion Stewart is Professor of Geology and Environmental Science at Georgia State University’s Perimeter College.

C. Bayard Stringer is Assistant Professor of Astronomy at Georgia State University’s Perimeter College.

Georgia State University, Perimeter College was known as Georgia Perimeter College at the time of the study.

This research was supported in part by a Perimeter College STEM Mini-grant, Funded by the University System of Georgia STEM II Initiative.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Mary Ann Cullen, University Library, Georgia State University, Alpharetta Campus, 3705 Brookside Pkwy., Alpharetta, GA 30022

Contact: mcullen@gsu.edu